Headlines

- After a respite, cold weather may try to re-emerge in mid-February in the eastern two-thirds of the United States.

- Hurricane Beryl’s post-season report was issued last week, and we got a few new nuggets of data to digest.

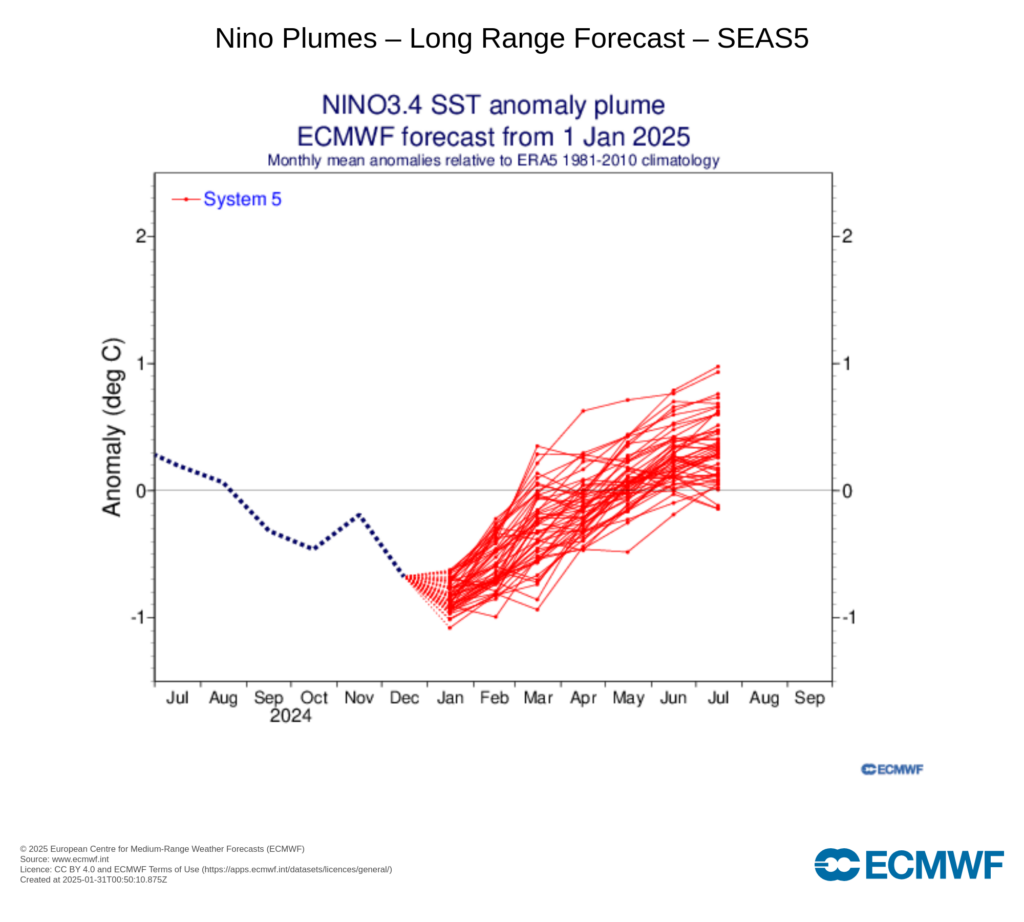

- La Niña became official in December, but what happens as we head toward summer may be in coin toss territory right now.

Winter may give it another go for the Midwest & East

Things are generally quiet in the weather space, or at least there are no real extreme impact events to discuss right now. That’s good at least. So let’s discuss the winter situation.

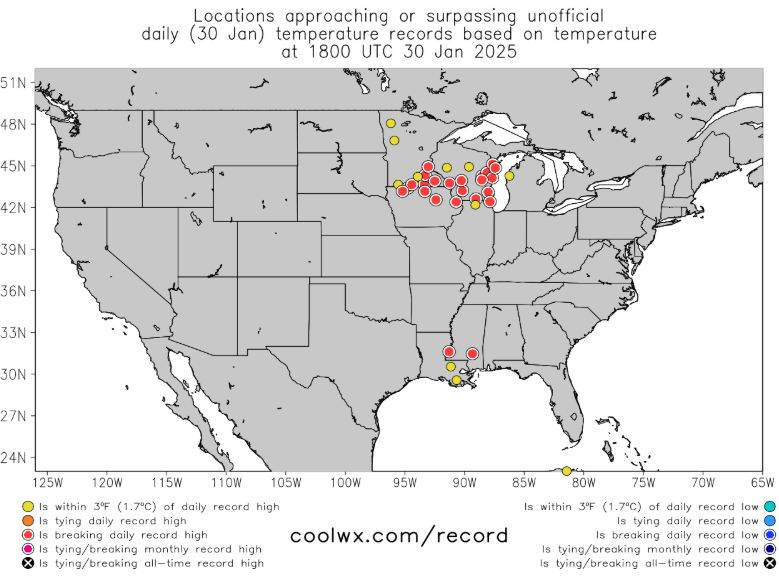

Numerous locations in the Upper Midwest saw temperatures break records today.

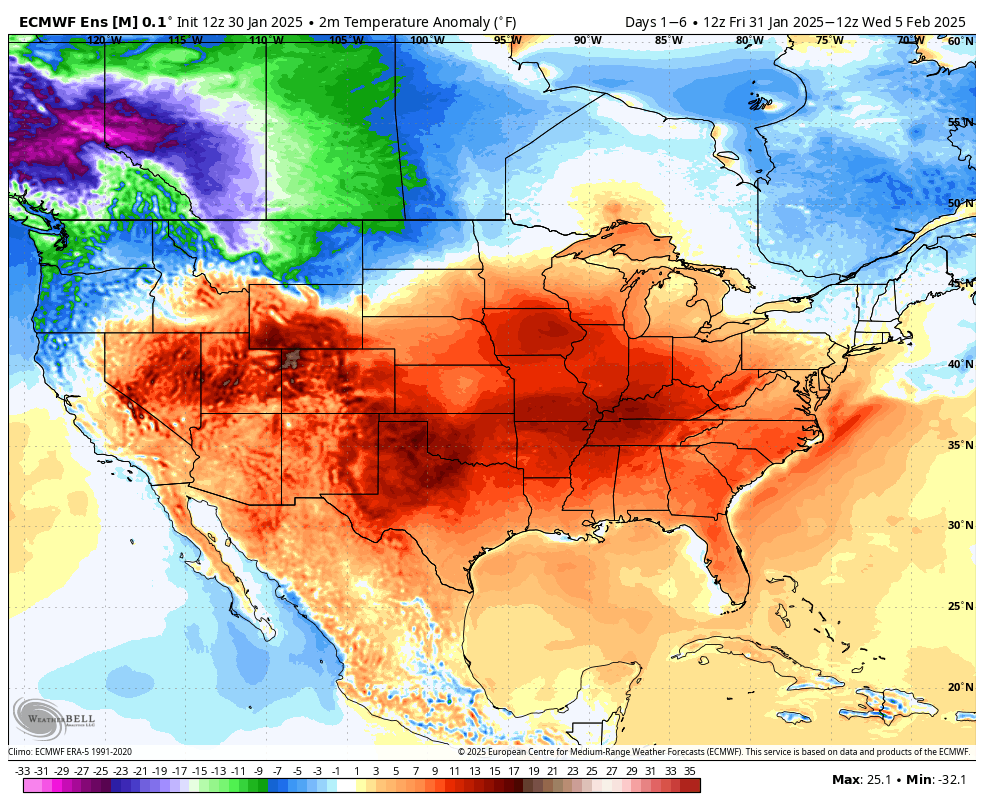

Since last week’s cold, much of the country has shifted back to warmer than normal weather this week. The exception to this is in the interior West. Over the next 5 or so days, this warm pattern is expected to continue.

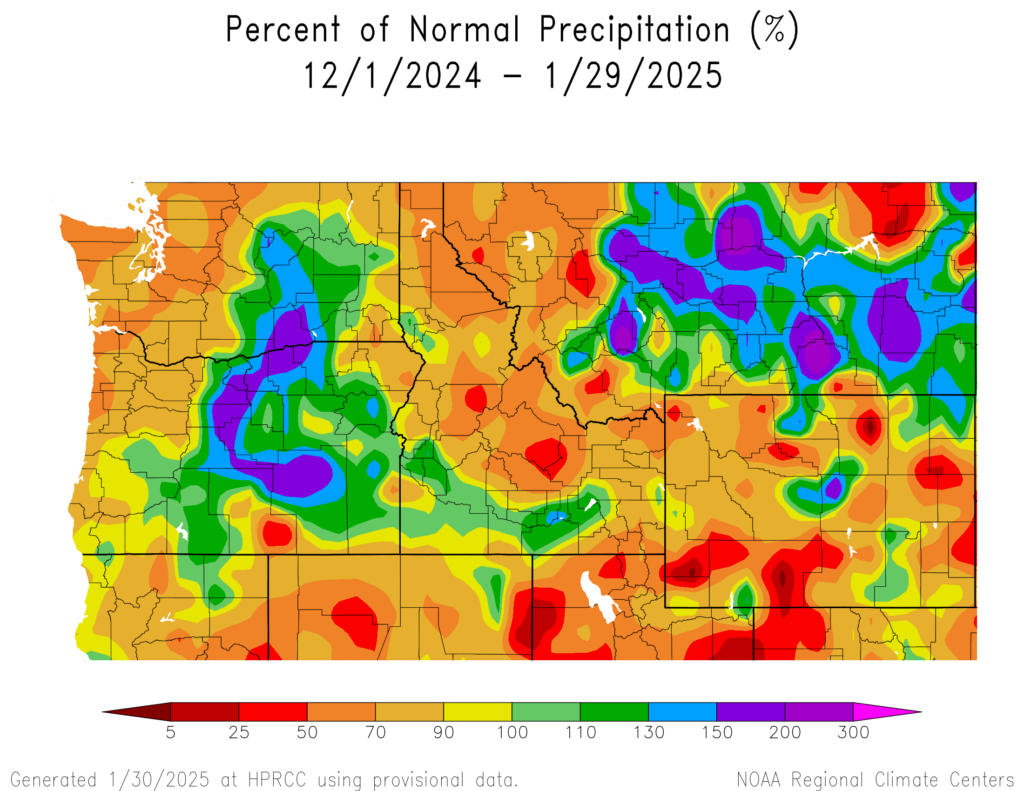

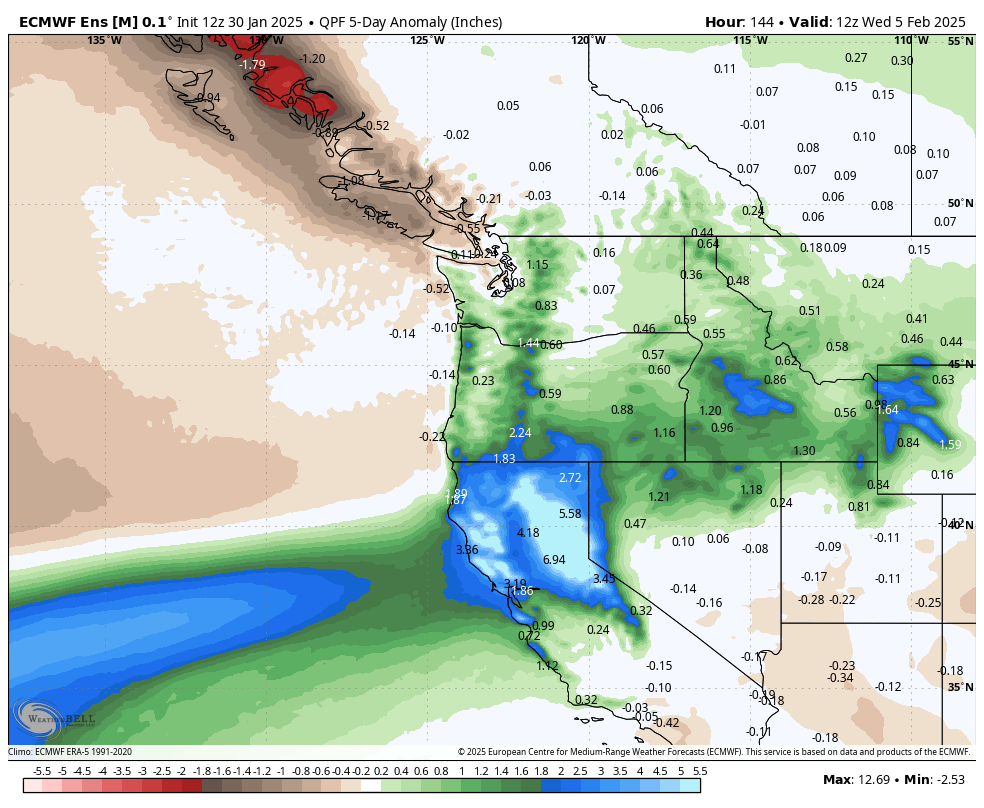

The Northwest will begin to see some stronger cold and also some solid mountain snow. This is an area that has had some very mixed results over the last couple months in the precip department. Portions of Oregon have done great, while much of Idaho, the Cascades and portions of the interior West have done not so great.

Portions of California are expected to really cash in, though unfortunately it will be mainly just the north, not Southern California. And places in the Northwest will be allowed to catch up over the next 5 days.

This looks to be about a category 4 on the atmospheric river scale, so this will be significant for those areas.

So, warmer nationally but a bit cooler and much wetter in the Northwest over the next 5 days. Then what?

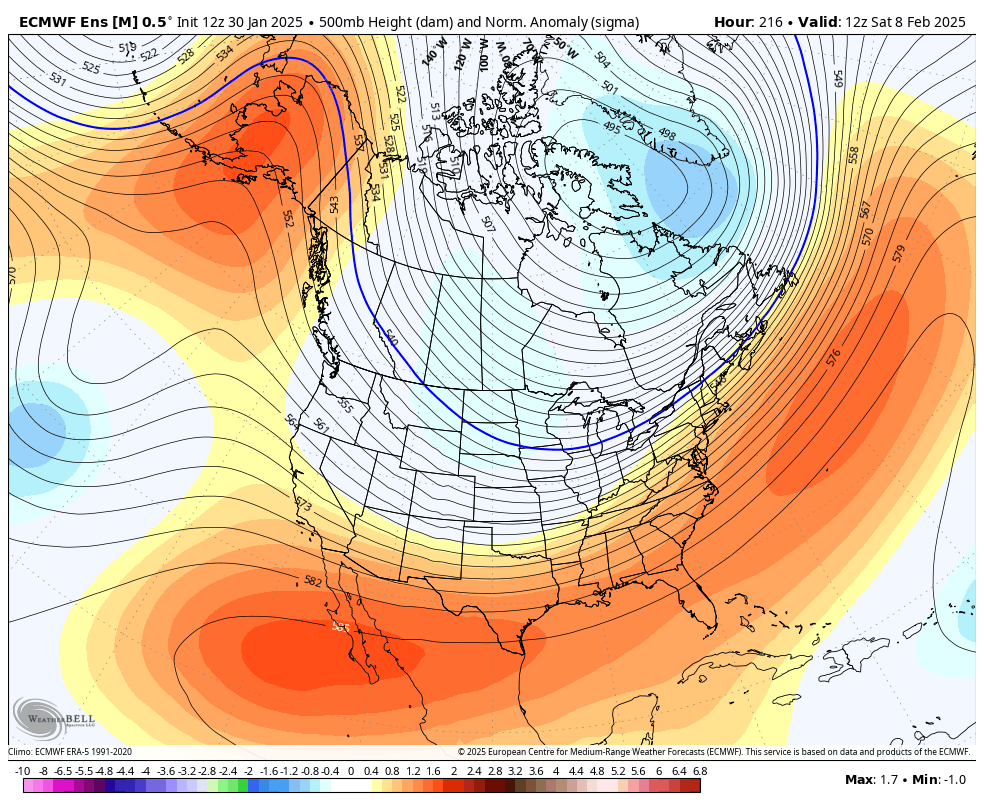

Well, changes are afoot again. When we look for cold risks in the U.S., we often look to Alaska. Frequently, what happens in the Continental United States (CONUS) is that when a large ridge of high pressure pokes up over Alaska, it tends to dislodge the cold and send it south and east. Exactly where that ridge establishes, its strength, its duration, etc. can all yield differences in outcome. But in general, for meaningful cold in the CONUS, you need that to happen in Alaska.

Well, the models are perking up a good bit about the potential for some meaningful ridging in the upper atmosphere over Alaska. In other words, they’re showing the pattern that would typically be favored to produce a colder Eastern U.S. In fact, today’s European ensemble model run shows basically a 2-sigma ridge over Alaska by next weekend. In plain language: That’s a potentially strong ridge.

Impressively, this shows up in the ensemble mean, which is an average of 51 different ensemble members. The signal is a bit weaker on the GFS model and in the AI modeling we look at, so nothing is guaranteed at this point. But with that said, there’s a signal here, and it’s one that says cold may reload for portions of the country where it’s currently absent. Something to watch in the days ahead.

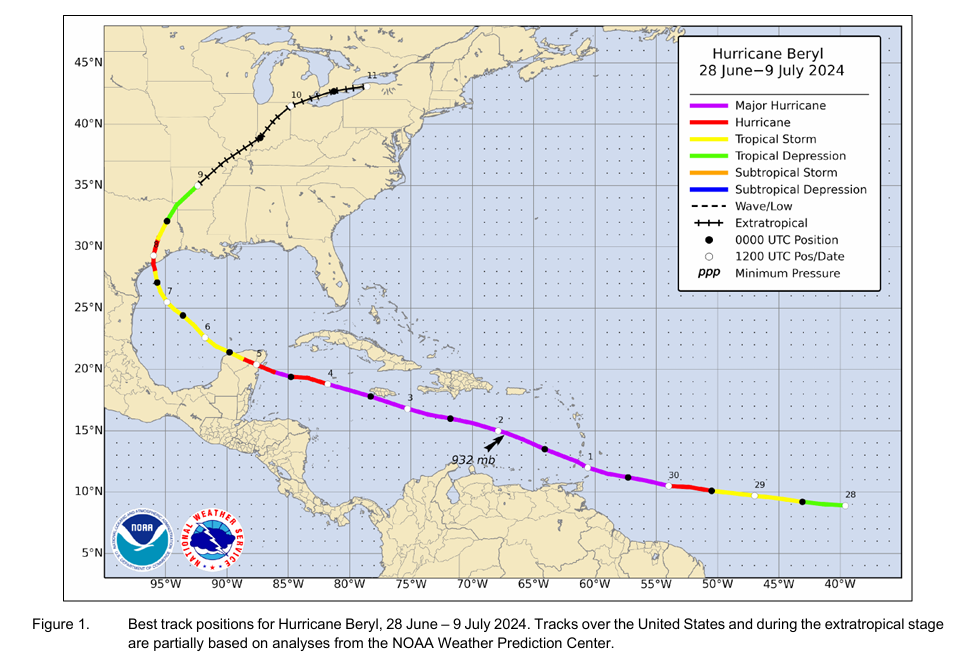

Hurricane Beryl’s post-storm report released

The National Hurricane Center released their post-storm report and analysis of Hurricane Beryl late last week. We did a deep dive on our companion site for Houston regarding some of the interesting findings with respect to the Texas landfall. Here are some other nuggets from the report.

Beryl was confirmed as the earliest category 5 storm on record in the Atlantic Basin. In the report, the NHC explains that while Beryl will officially go in the books as a 165 mph category 5 hurricane, there is a bit of ambiguity in that the peak intensity may have been slightly overestimated by the various methods utilized to estimate the intensity. It’s likely that if that peak intensity is incorrect, it is not off by much. Beryl made landfall with roughly 135 to 140 mph sustained winds on Carriacou Island in Grenada. No reliable observations of wind speed exist in that area.

Notably, Beryl’s landfall intensity was reduced significantly on the Yucatan. In real-time, it was assumed to have 110 mph winds. In the reanalysis, it is estimated to have maximum sustained winds of 90 to 95 mph. And then as we note in our Space City Weather post linked above, the landfall intensity was increased to 90 to 95 mph in Texas, up from 80 mph estimated in real-time.

A number of milestones prior to August were achieved due to Beryl including strongest storm (165 mph) so early in the season on record in the Atlantic, besting 2005’s Hurricane Emily in July (160 mph). I think one of the most impressive records Beryl matched though was the fastest rate of intensification (65 mph in 24 hours) so early in the season on June 29-30, matching July 2008’s Hurricane Bertha. Additionally, Beryl is now the storm of record for Grenada.

Beryl was a challenging storm in many respects, between impacts and forecasts. We learned a lot that helped us a lot through the balance of hurricane season, but you can be sure that Beryl will be on the list of names to be retired this year, likely including Helene and Milton.

La Niña checkup: It’s here, but will it stay?

Last we discussed La Niña, it was likely in the context of how the rest of hurricane season would behave or why the season did not quite go as planned.

It took some time, but we officially had La Niña designated in December. So it’s here. That said, it’s not an especially strong one. This is one of the weaker first year La Niñas in recent years, I am guessing since at least 2016-17 or 2013-14. That’s not to say it won’t have impact. The dryness in SoCal and wetter conditions to the north are usual hallmarks of a La Niña, though it has been magnified to an extreme this year. Even weak La Niñas can aggravate other factors and cause major problems.

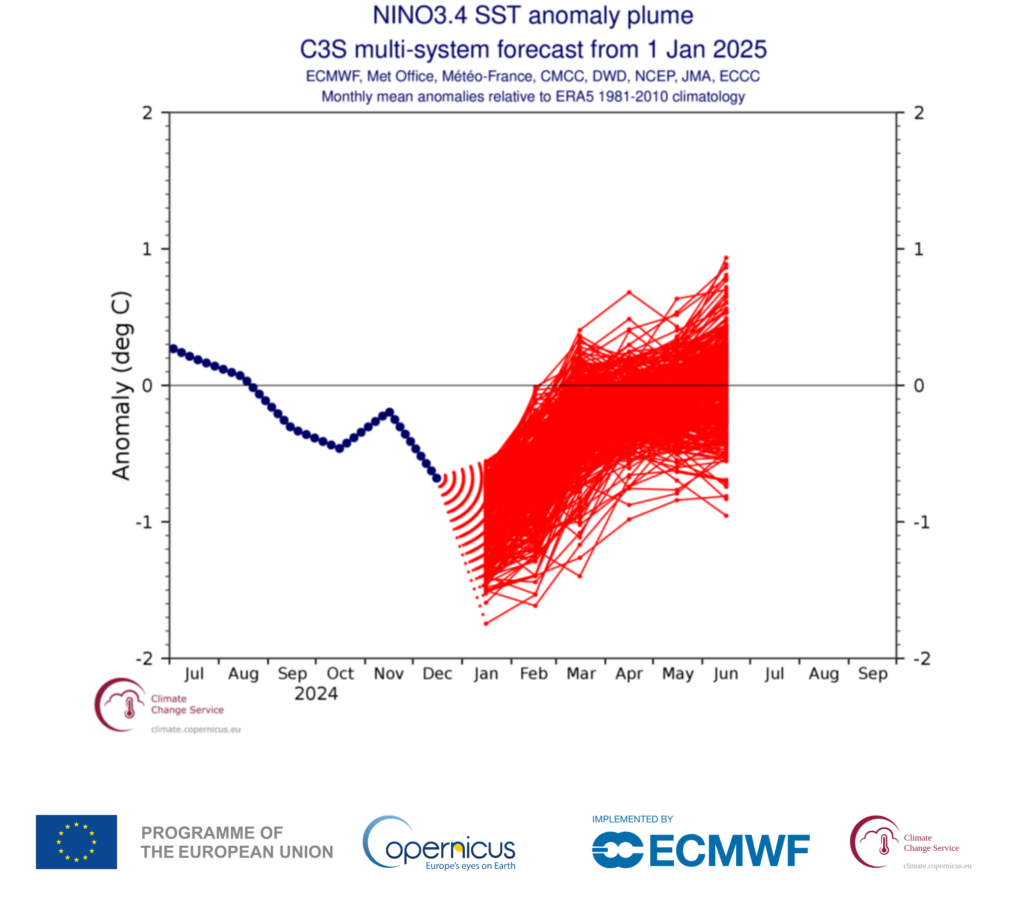

Per the ECMWF forecast above, we may shift into El Niño conditions in summertime. However, a look at the broader group of seasonal forecast models from eight different government agencies paints a much murkier picture.

We are entering what is known as the spring predictability barrier, where for some reasons that aren’t entirely clear, seasonal forecasting of El Niño or La Niña struggle. So, it’s wise to take everything with a grain of salt right now. We’ll continue tracking this as we head toward hurricane season, as it can have significant impacts on the season’s projected trajectory. Stay tuned.

Good info – I sure hope it’ll turn to El Niño – 2005 was neutral/weak La Niña & 2020 was weak La Niña.

Man I can’t believe we’re already talking about hurricanes again – last year wiped me out. I used to enjoy learning all about hurricanes & storms, riding out the smaller ones.

Not any more.

Very interesting.

Very interesting, keep it up.