In brief: Invest 92L became Tropical Depression 3 yesterday and is now Tropical Storm Chantal. It’s en route to the Carolinas. We take a detailed look at what occurred in Texas Thursday night and Friday morning.

Note: Most of the data in these posts originates from NOAA and NWS. Many of the taxpayer-funded forecasting tools described below come from NOAA-led research from research institutes that will have their funding eliminated in the current proposed 2026 budget. Access to these tools to inform and protect lives and property would not be possible without NOAA’s work and continuous research efforts.

Tropical Storm Chantal

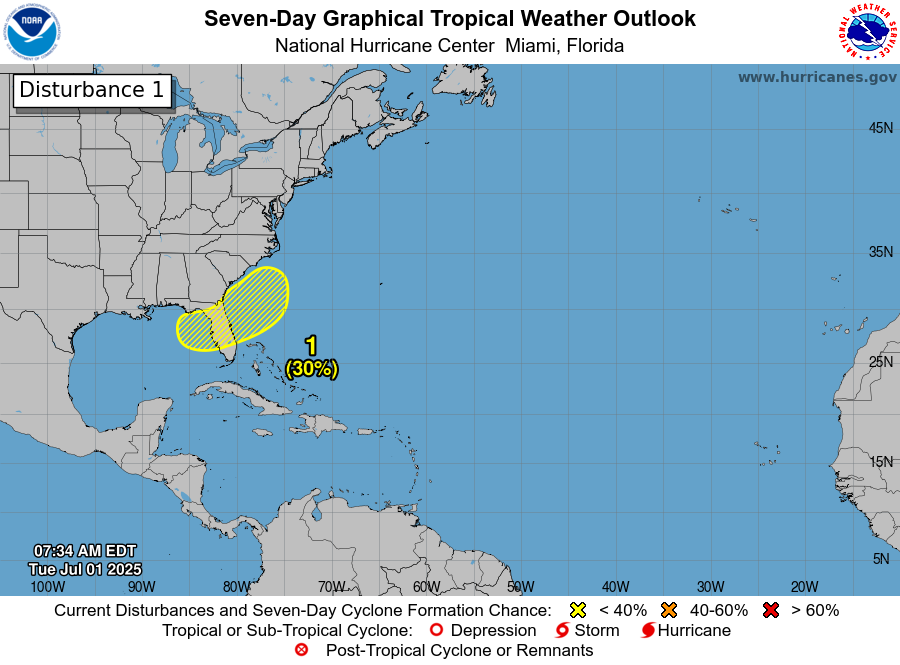

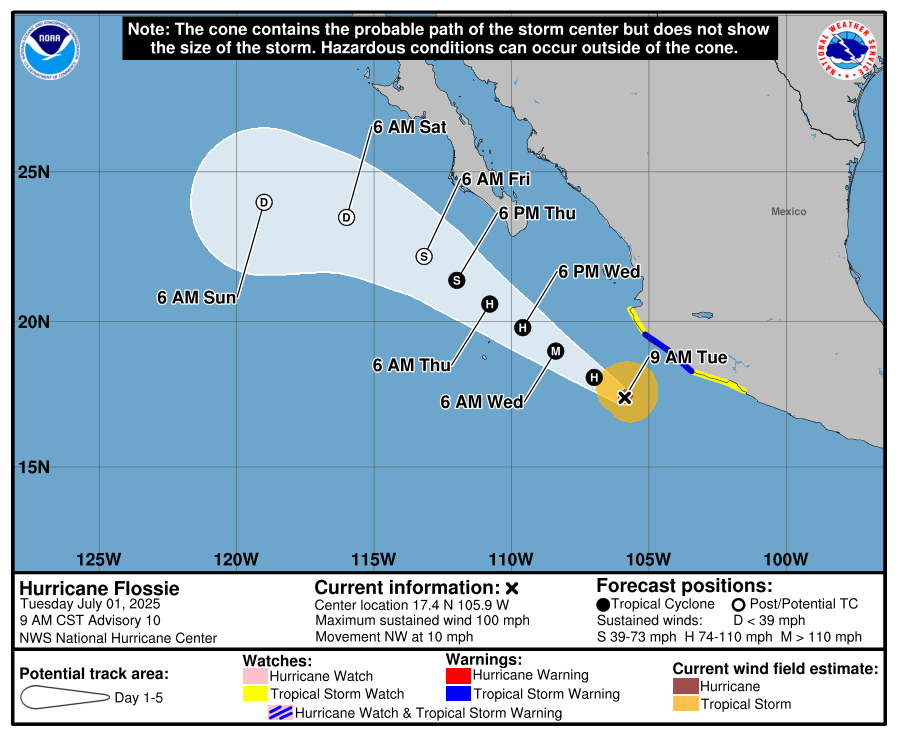

Hot off the presses this morning, Tropical Depression 3 is now Tropical Storm Chantal, giving us a 3 for 3 conversion rate of depressions to storms so far this season.

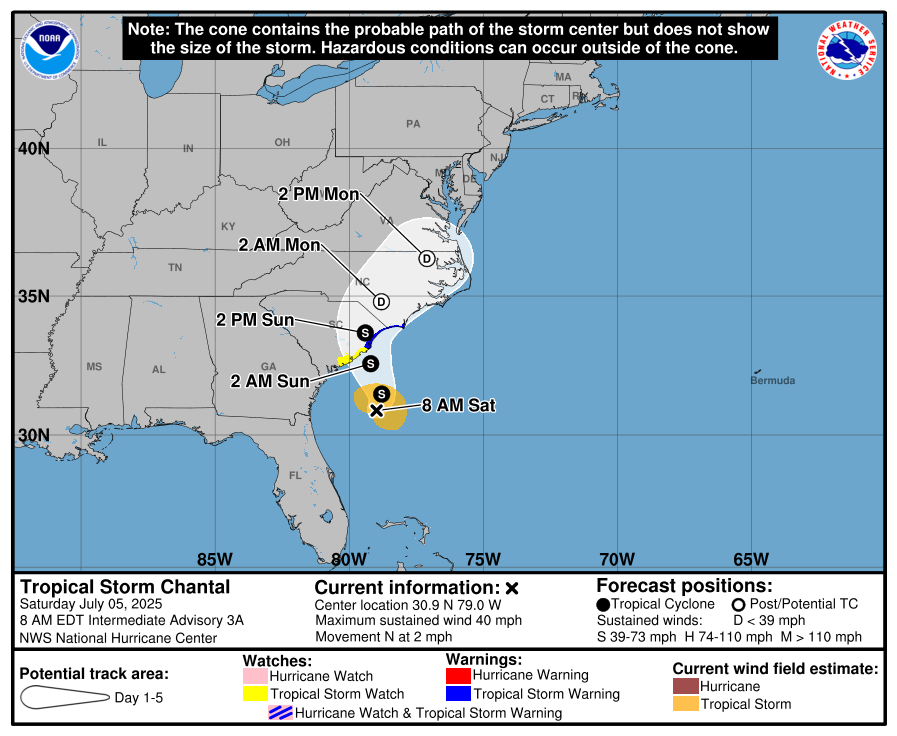

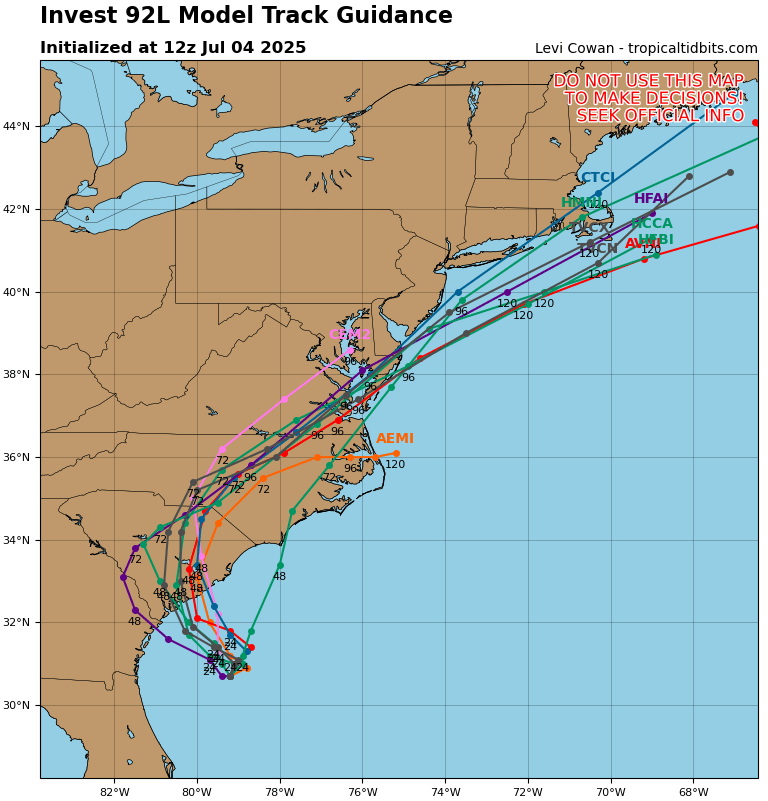

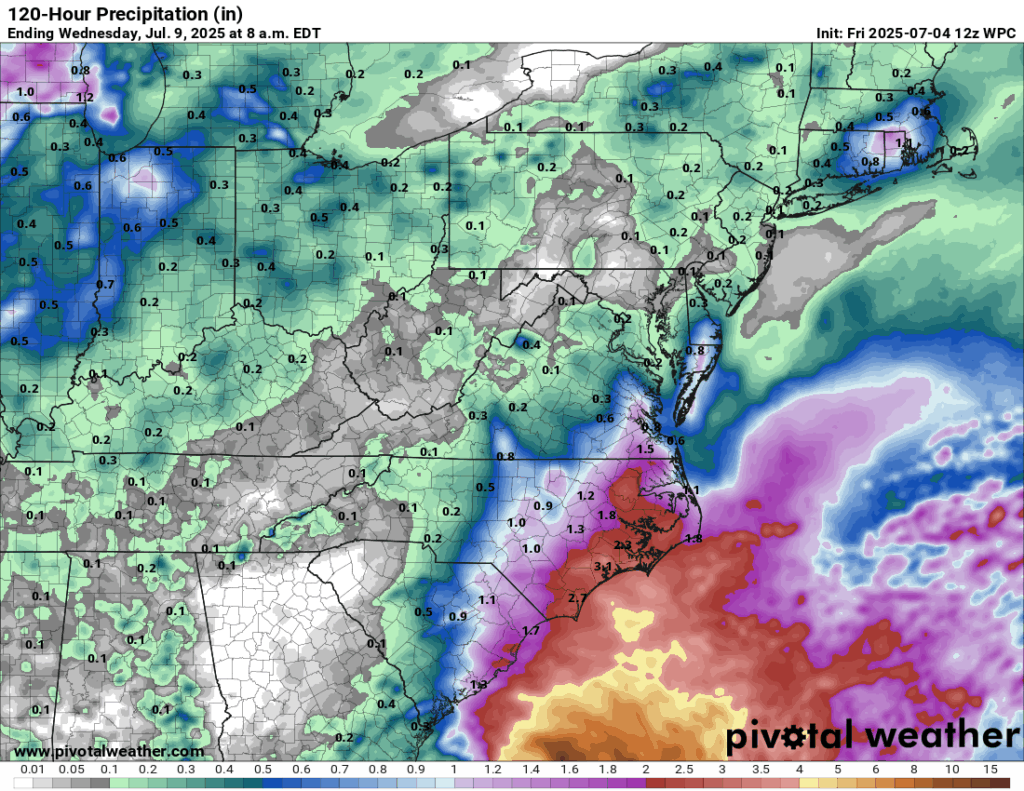

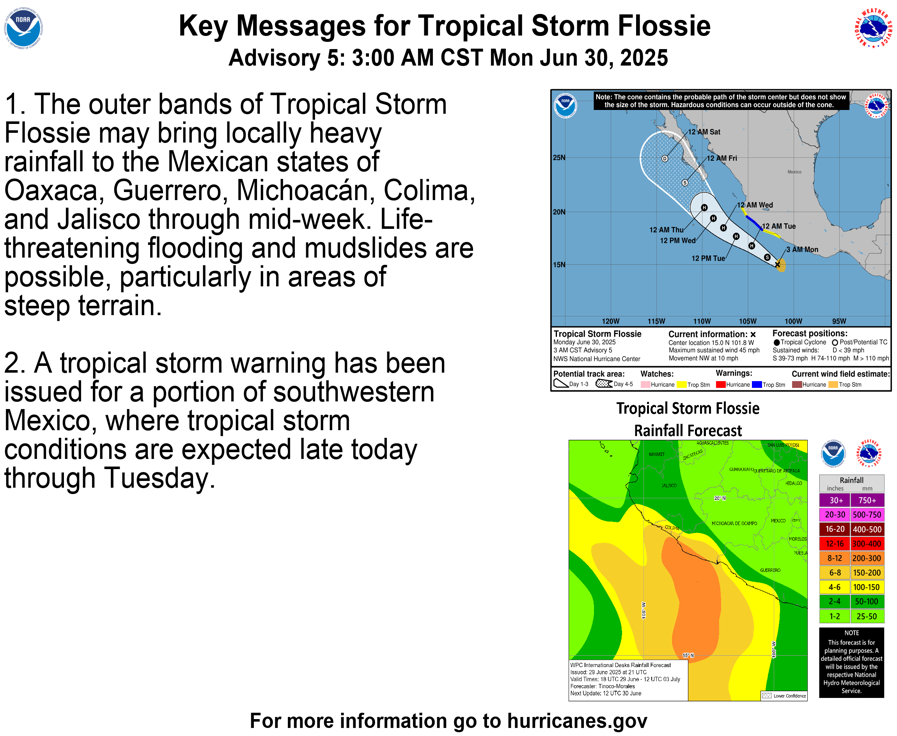

Chantal’s forecast has not changed a whole heck of a lot since yesterday, as impacts will remain primarily heavy rain and localized flooding, as well as rip currents on the beaches. Please exercise caution, particularly on the Carolina coasts and a little farther north. Chantal will remain over fairly warm water for the next 18 to 24 hours, so it may try to strengthen a bit further. Tropical storm warnings include the upper South Carolina coast, including Myrtle Beach, as well as extreme southeast North Carolina.

Chantal will continue north and east after tomorrow dissipating before it gets to Delmarva.

Unraveling what happened in Texas

First, as someone based in Texas and with multiple members of our large but still close community still missing, I want to extend whatever sort of condolences are possible to friends and family that are dealing with what is truly an unspeakably horrific tragedy. On a holiday weekend that should be celebratory for kids and families no less, in the middle of the night when they’re at their most vulnerable. There truly are no words.

What we can do is take stock of what happened, explain why, explain what was known and what wasn’t know, and try to piece together how something like this happens in 2025.

The cause

As is often the case in interior Texas, one of the culprits involved last night was the remnant of a tropical system. Remember Tropical Storm Barry? It lasted all of 12 hours before coming ashore in Mexico. We can track Barry’s remnants from landfall last weekend through Thursday evening by looking at its “fingerprint” about 10,000 feet above the surface.

So you had the remnants of a tropical storm. Because of this, you had abundant moisture coming from that storm’s source region in the Gulf. You had strong moisture transport coming northward as well with a strong low-level jet stream (a common feature in Texas located about 5,000 feet above the surface). But the jet was oriented to allow for maximum upsloping, aimed right at Hill Country. You had plentiful instability in the atmosphere as well.

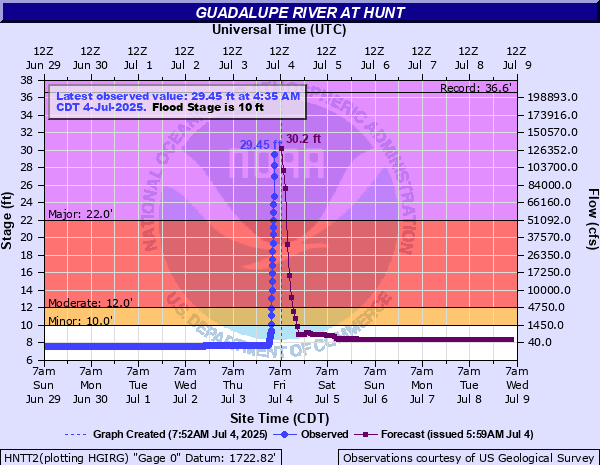

So, tallying all that together: A remnant tropical system, moisture levels in the 99th percentile or higher, forced upward motion due to geography and wind direction, and plentiful instability. That’s a recipe for flash flooding. So how do you go from flash flooding to catastrophic flash flooding, because the difference is clearly enormous. When you put those parameters in concert with a weather pattern that allows for maximum efficiency of rainfall, a monsoonal pattern, and slow movement, as well as geography that allows for rapid build up of water on dry ground and riverbeds that “funnel” that through an area, that’s when you flip from ordinary to potentially tragic.

The forecast

Beginning last Sunday morning, forecast discussions from the NWS office in San Antonio and Austin noted the potential for heavy rain through the week. By Monday morning, they also noted the potential for nighttime warm rain processes in the western part of their coverage area, which would probably include Kerrville. By Tuesday afternoon they had specifically mentioned the potential for flooding on Thursday. Nothing really changed messaging wise on Wednesday or Thursday morning. By the afternoon, flood watches had been hoisted as the potential for significant rain became more evident.

Modeling? Well, it was so-so. When it comes to heavy rain, the lower resolution global models can give you a sense of what may happen, but they’re generally unable to resolve where the heaviest rains will fall. I went back and looked at some of the model rainfall forecasts for the event this past week. While some of the global models did indicate heavy rainfall potential, none were really flagging a high-risk type event. Even on Thursday morning, the WPC Excessive Rain Outlook showed a slight risk (2/4) in the area. We could probably say that the catastrophic rains were isolated enough that this was still reasonable. But truth be told, this probably deserved a moderate.

Within their discussion, they did emphasize risks of 3 inches or more, which is a reasonable note to make.

The higher resolution models did do better and did lead everyone down the correct path. On Wednesday night, the 00z HRRR model had about 7-9″ in a few bullseyes between Mexico and Texas by Friday morning. By Thursday morning, the model showed as much as 10 to 13 inches in parts of Texas. By Thursday evening, that was as much as 20 inches. So the HRRR model upped the ante all day.

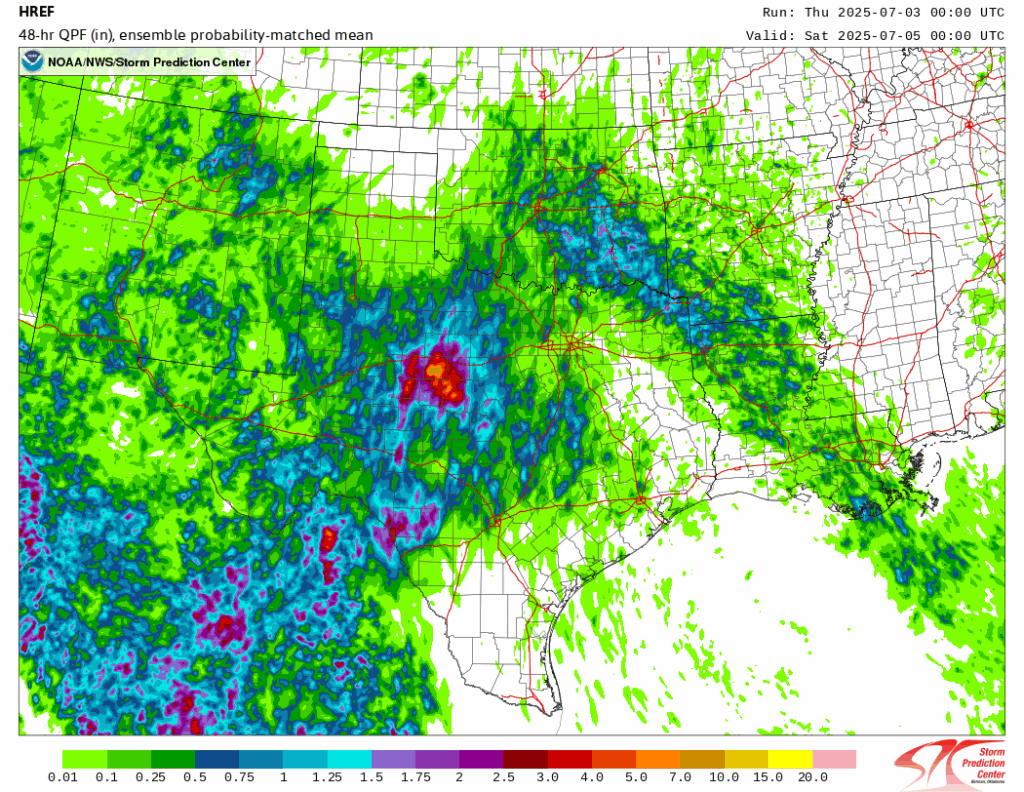

The HREF model on Thursday morning, a tool developed from NOAA research also indicated the risk of 10″ or more in spots, using the “probability matched mean” product which can identify higher risk areas for heavy rainfall. I’ve used this in Houston many times, often with considerable forecast success ahead of flooding events. It has a knack for cutting through some of these higher end events and highlighting those risks.

So the signals were there and got worse as Thursday progressed. Messaging and flood watches responded to this appropriately and expanded into Thursday evening.

The warnings

Flash flood warnings were issued for areas before midnight as radar rain totals began to inflate up and over 3 to 4 inches. A flash flood emergency was issued at 4 AM for the Kerrville storms and 4:15 AM for storms near San Angelo. Rain totals were estimated to be encroaching on 10 inches at that point. So there was warning. This NWS office is acutely aware of the threats to the area from flooding, and the history is there. So I am assuming they were timely warnings unless I hear otherwise.

Issuing the warning is half the process. Were the warnings received and acted on? That’s another story. And that will also come out in the days ahead. More on that below.

Did budget cuts play a role?

No. In this particular case, we have seen absolutely nothing to suggest that current staffing or budget issues within NOAA and the NWS played any role at all in this event. Anyone using this event to claim that is being dishonest. There are many places you can go with expressing thoughts on the current and proposed cuts. We’ve been very vocal about them here. But this is not the right event for those takes.

In fact, weather balloon launches played a vital role in forecast messaging on Thursday night as the event was beginning to unfold. If you want to go that route, use this event as a symbol of the value NOAA and NWS bring to society, understanding that as horrific as this is, yes, it could always have been even worse.

What should we be asking about then?

Beyond the fact that this was truly a tragedy that is extremely difficult to disseminate warnings on, I think we need to focus our attention on how people in these types of locations receive warnings. This seems to be where the breakdown occurred.

It’s not as if catastrophic flash flooding is new in interior Texas. There are literal books written about the history. The region is actually referred to as “Flash Flood Alley.” But how we manage that risk is crucially important context here. Are there sirens in place? Do there need to be sirens in place? Would people even hear sirens in the middle of the night in cabins or RVs or wherever they were? Tornado sirens have traditionally been used in parts of the country for people outdoors to get warnings. Is that an appropriate method in this region for the middle of the night and indoors?

Do we need to start thinking of every risk of flooding in Texas as a potential high-end event we should pre-evacuate the highest risk people (like children and elderly in floodways) for? Is that even practical? We can critique the answer given by the Kerr County judge here all day, but he’s correct in that the reality is they deal with flooding a lot. What is actually practical? I don’t know the answers to these questions. But it’s been a little over 10 years since Wimberley, which was a wake up call in some ways too. It’s time for another, and we need to think much bigger than just the areas impacted this time and more about Flash Flood Alley as a whole. Flooding risk is high in Texas. People learn to live with it in some ways. But something like this absolutely cannot happen again. The Texas legislature meets for a special session beginning on July 21st. This may be an important topic to add to the agenda.