In brief: A winter storm may bring some minor snow accumulations to rather far south latitudes this weekend, including perhaps all the way to northern Florida. That will be followed by some cold and the potential for some healthy cold later next week in the North. In addition, we’re going to see some wild winds in the Plains, and we’re also actually looking at the Eastern Pacific for possible tropical development.

Hello after a bit of a hiatus! Let’s get into some winter.

Florida flakes?

I’m presenting at the annual meeting of the American Meteorological Society later this month here in Houston on comparisons between last January’s snow that established a new state record in Florida and covered much of the Gulf Coast in white and an 1895 event that had some similarities. Gulf Coast snow is somewhat rare, certainly uncommon, so it’s newsworthy whenever it happens. And indeed, as we approach this weekend, we’re at it again!

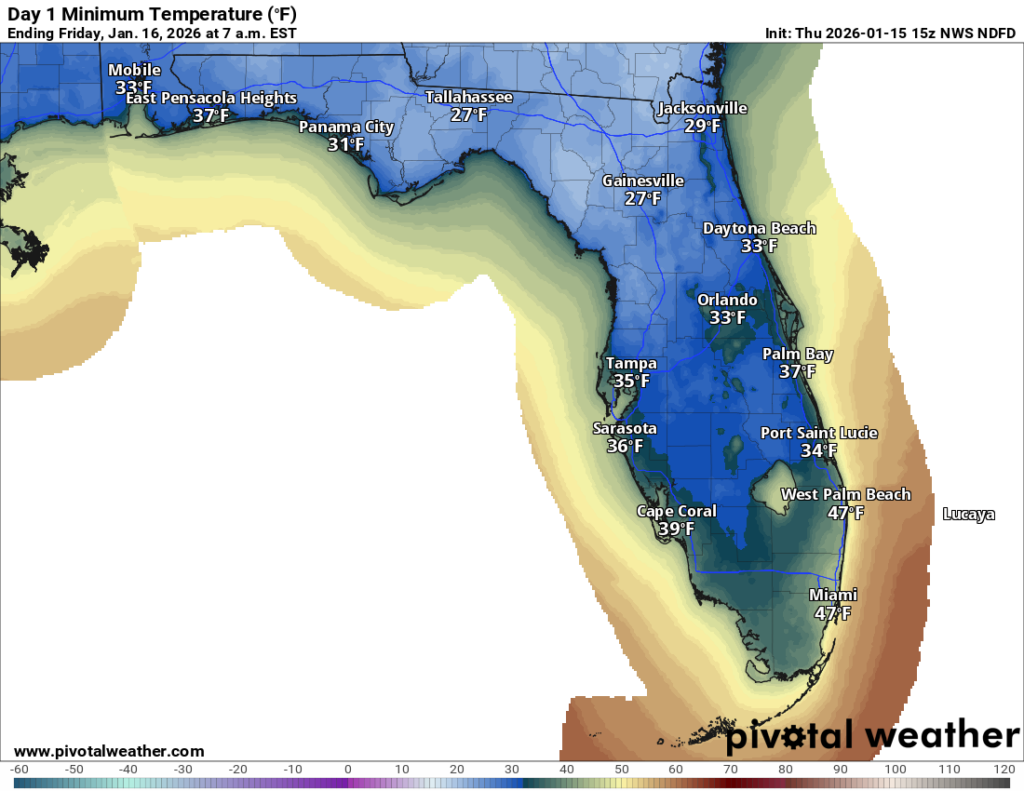

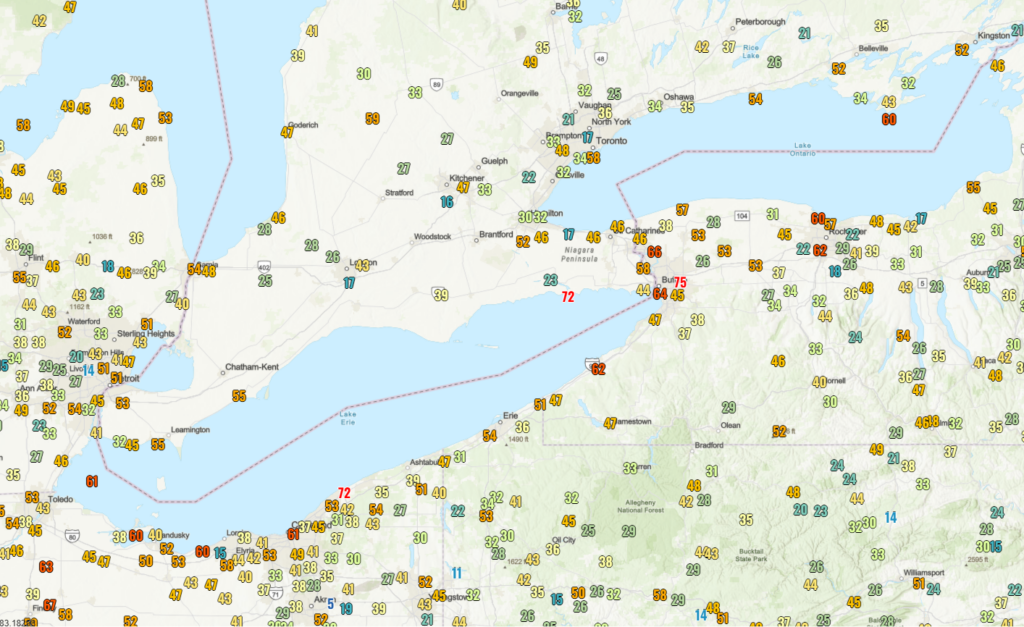

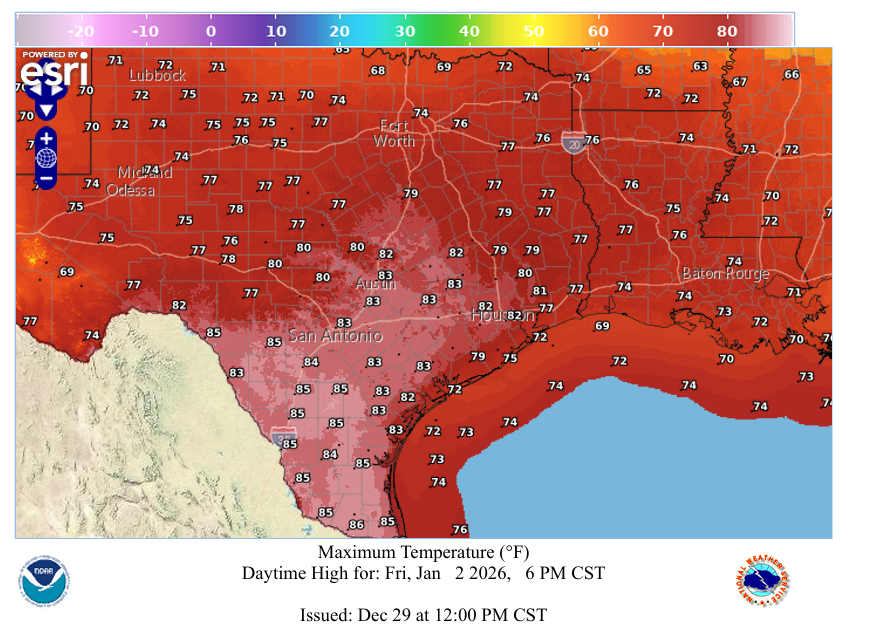

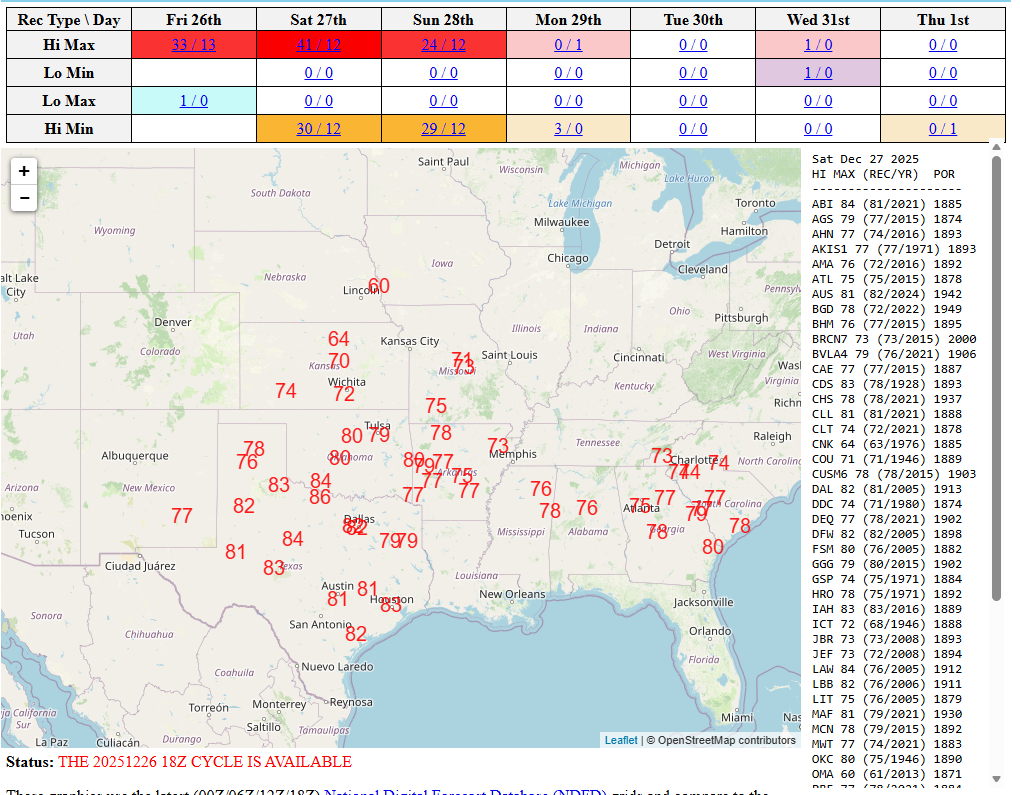

As this week has progressed, we’ve begun to see the beginnings of a pattern change, starting with a pretty potent upper level trough of low pressure digging into the Eastern U.S., deep into the Southeast. Low temperatures tonight are expected to be in the 20s in the Florida Panhandle and 30s down to Tampa and Orlando.

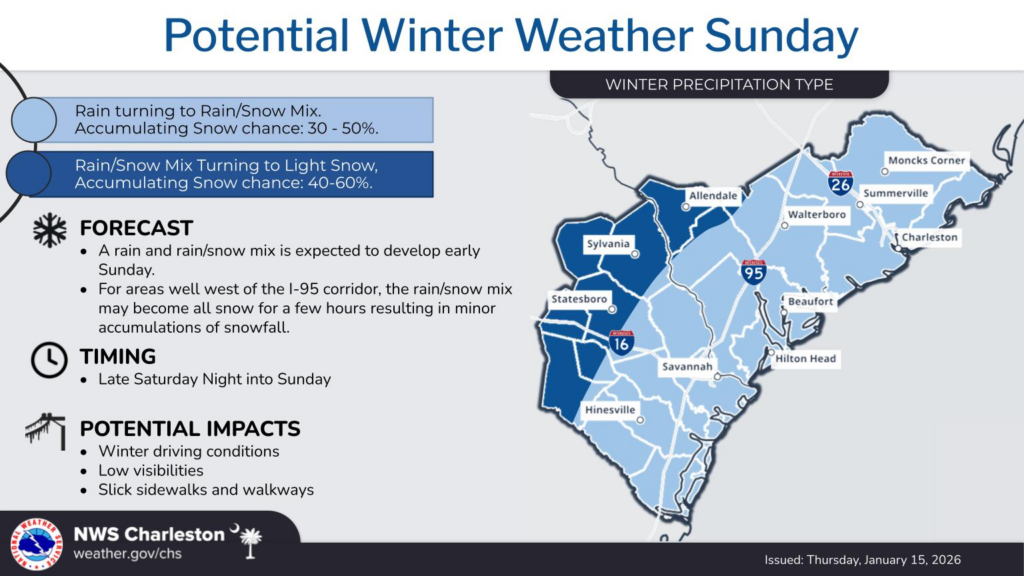

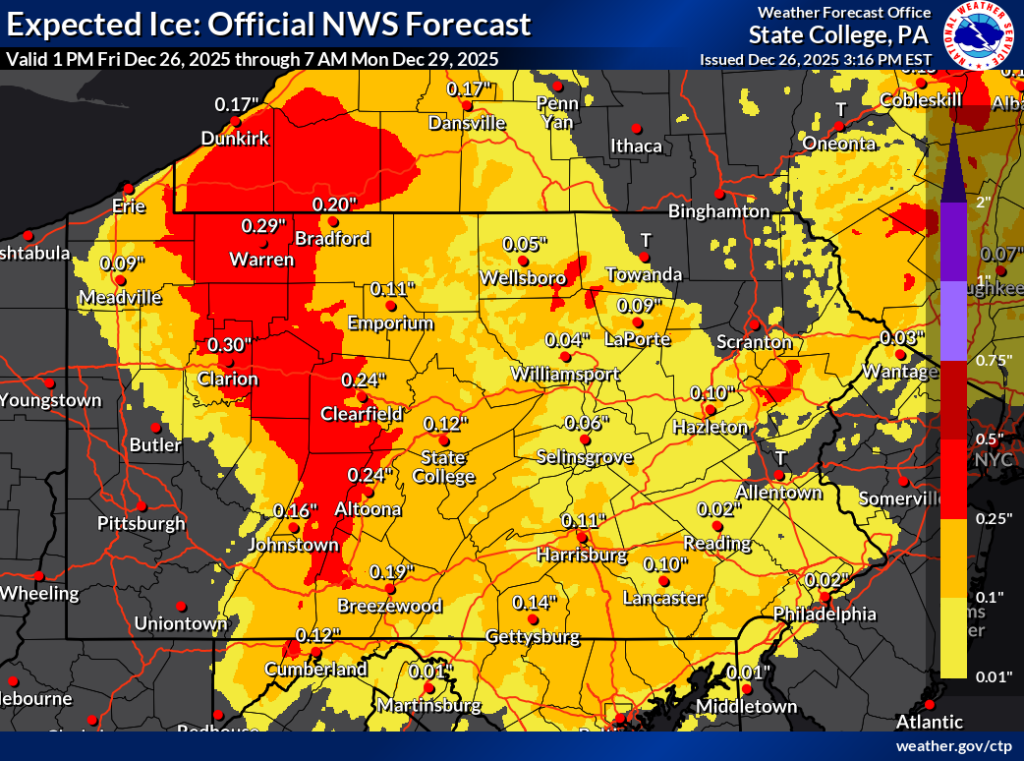

After a brief push of moderation, the weather will again turn colder this weekend as a very sharp disturbance within the trough carves out near Texas and Louisiana and pushes east off the East Coast. As this happens, a shield of rain is going to develop off the Texas and western Louisiana coasts in the Gulf and rocket east northeast. Because the trough is so deep, the storm track will be somewhat suppressed, meaning any low pressure that forms will be off the South Carolina or Georgia coasts.

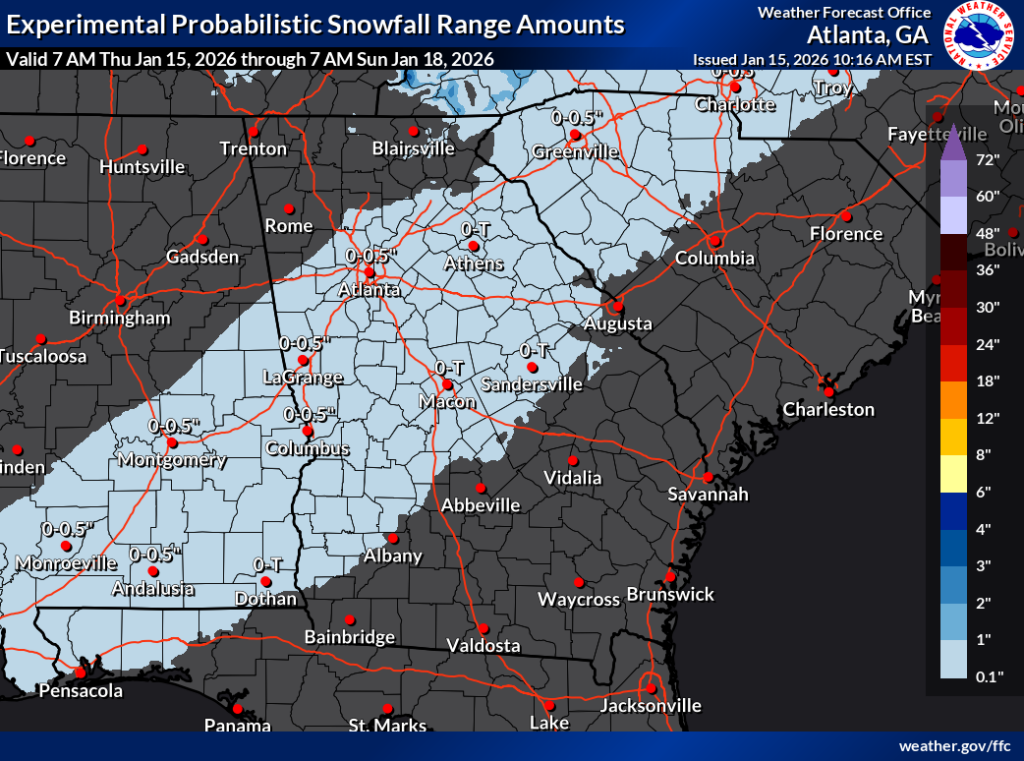

With cold air moving back in place on the backside of this storm, it seems possible, if not likely that rain will mix with or change to snow over parts of the Southeast. While this probably won’t be a major snowstorm, the prospect of a few inches of snow in some parts of the Southeast, say from the Florida Panhandle, across south Georgia, into South Carolina is definitely interesting!

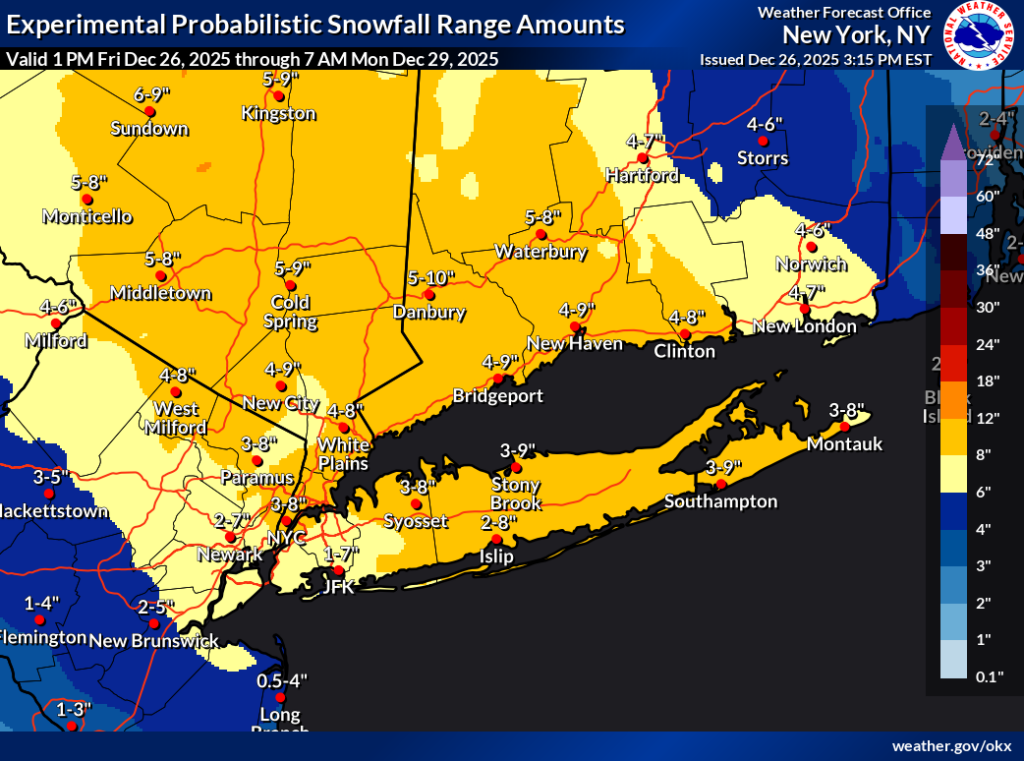

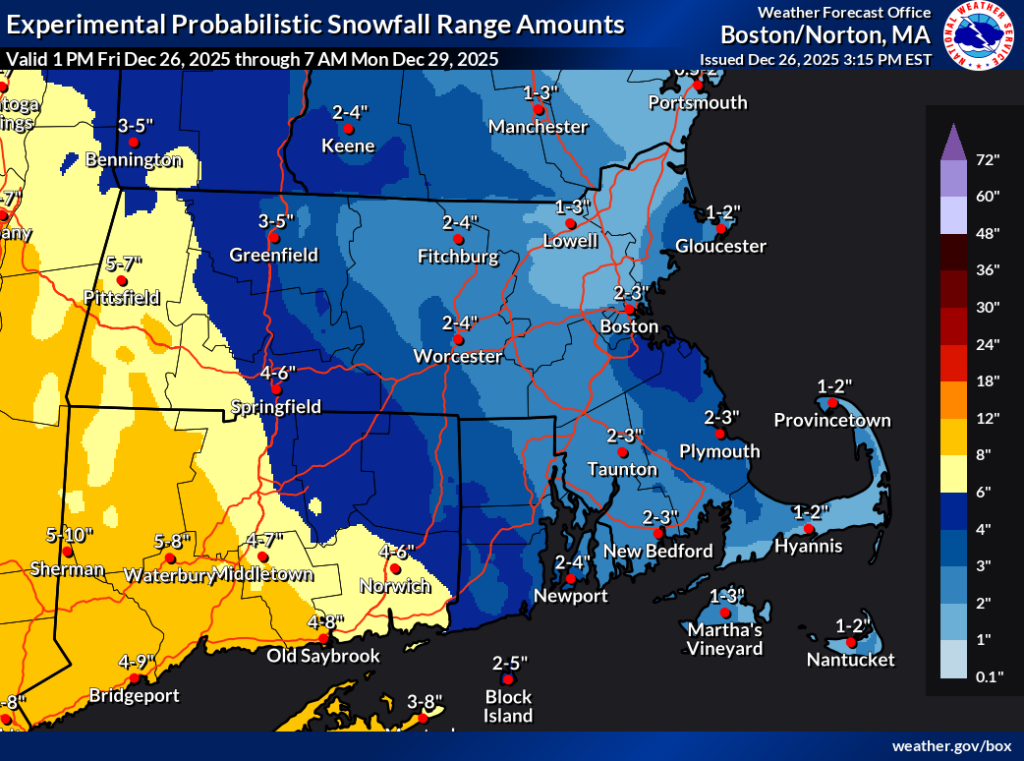

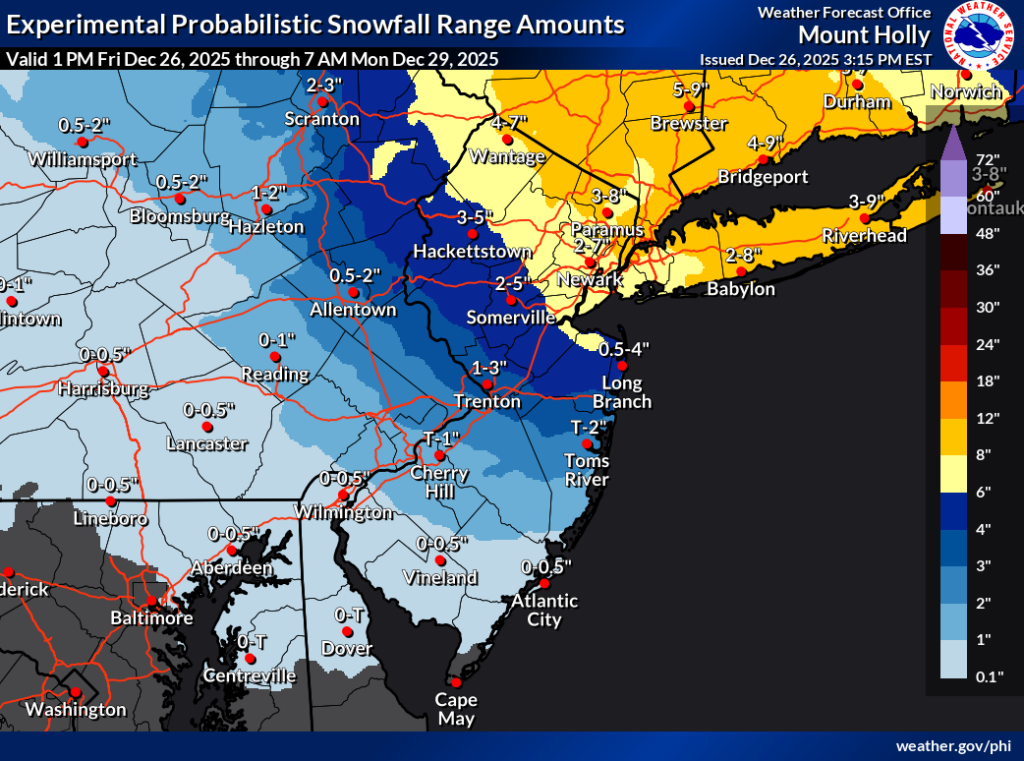

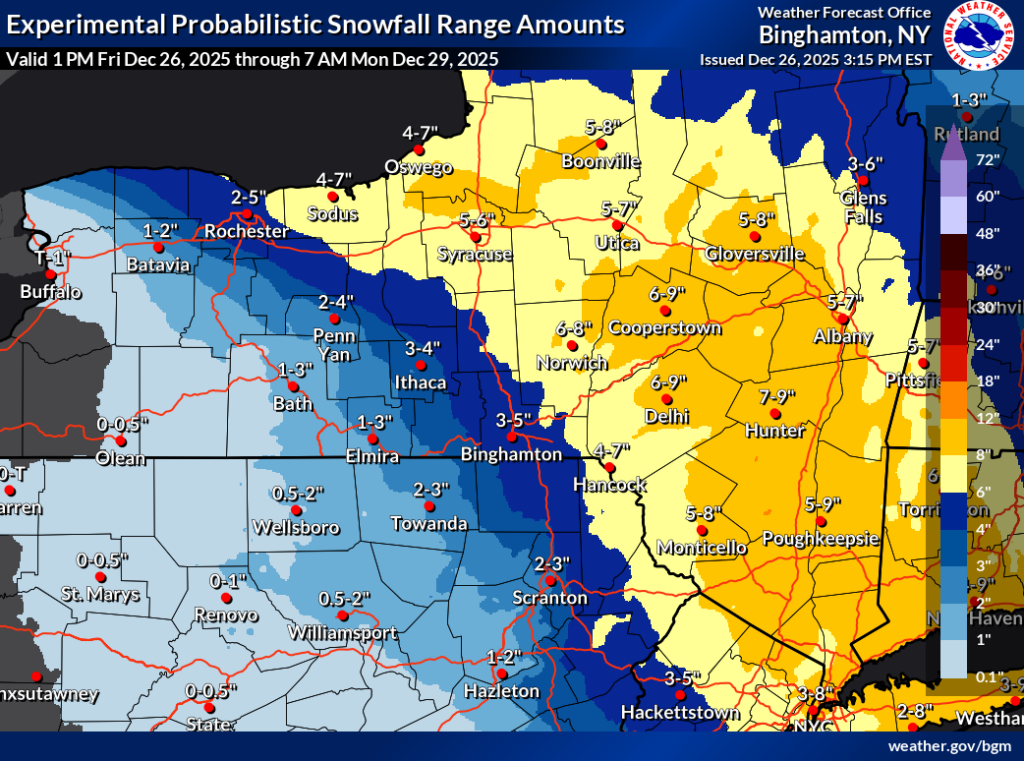

The area most likely to see something on the order of 1 to maybe up to 3 inches of snow is likely from north of Tallahassee through Valdosta into maybe Augusta and Columbia, SC. Current snow forecasts are not exactly major through 7 AM on Sunday, but it’s something! Keep posted to your local forecasts in the South for more over the next couple days.

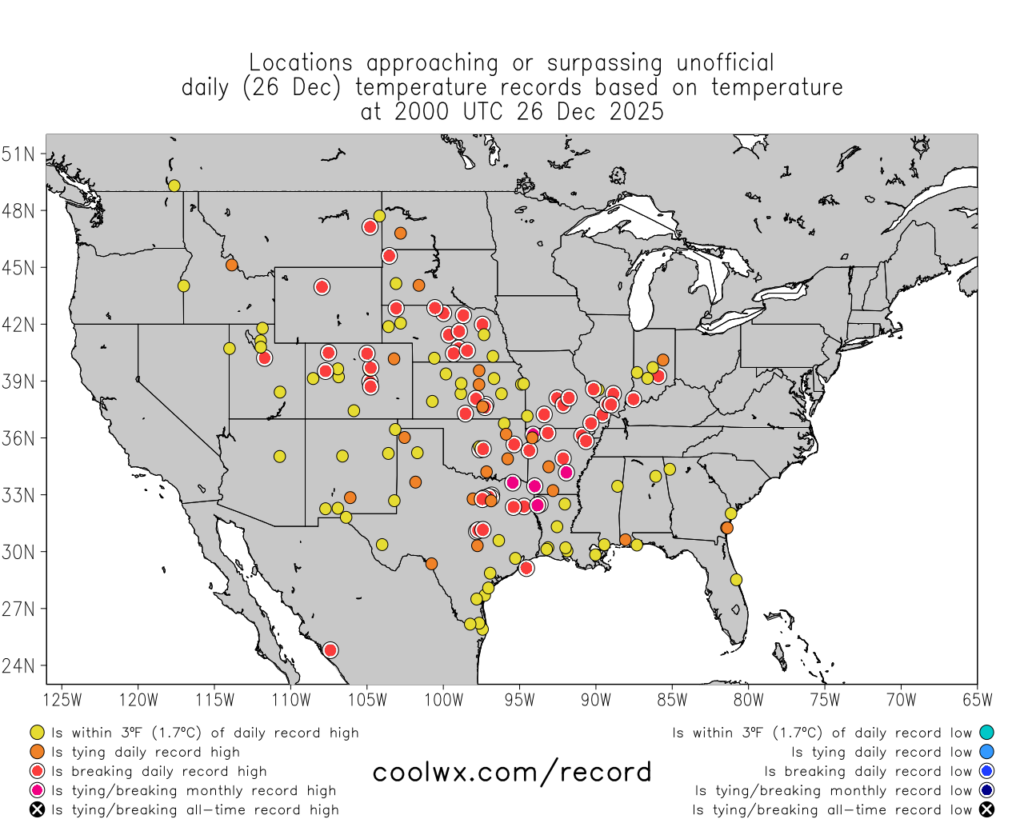

Let’s welcome winter back to the Southeast after what has been a rather lengthy stretch of mostly mild, at times record warm weather.

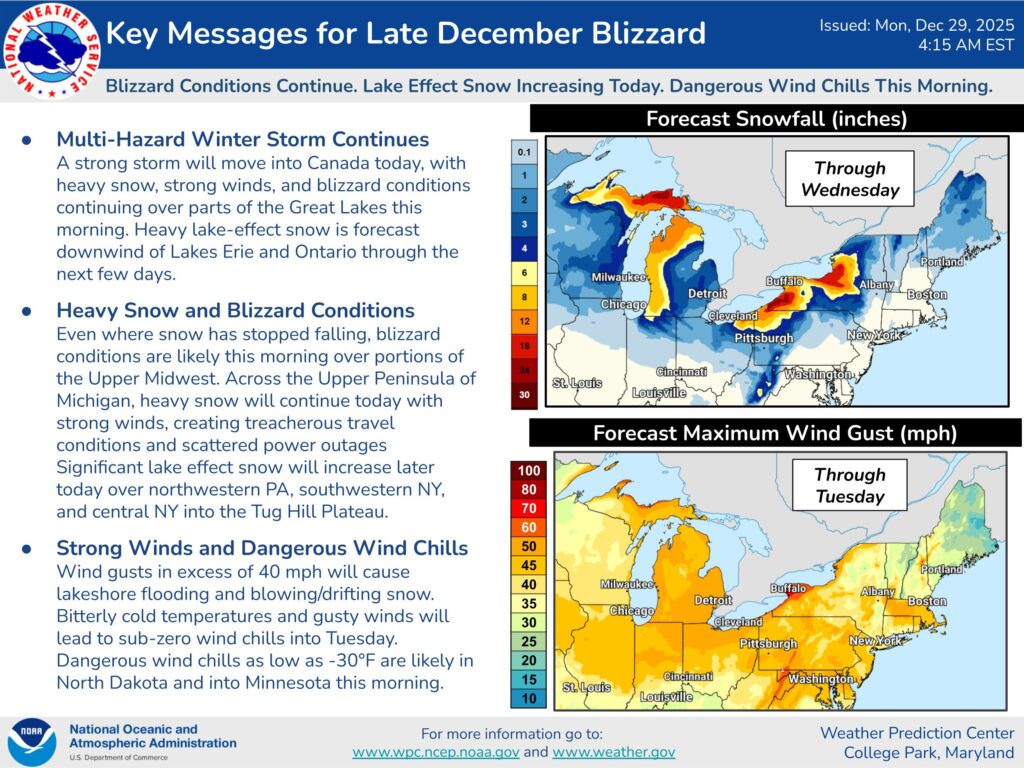

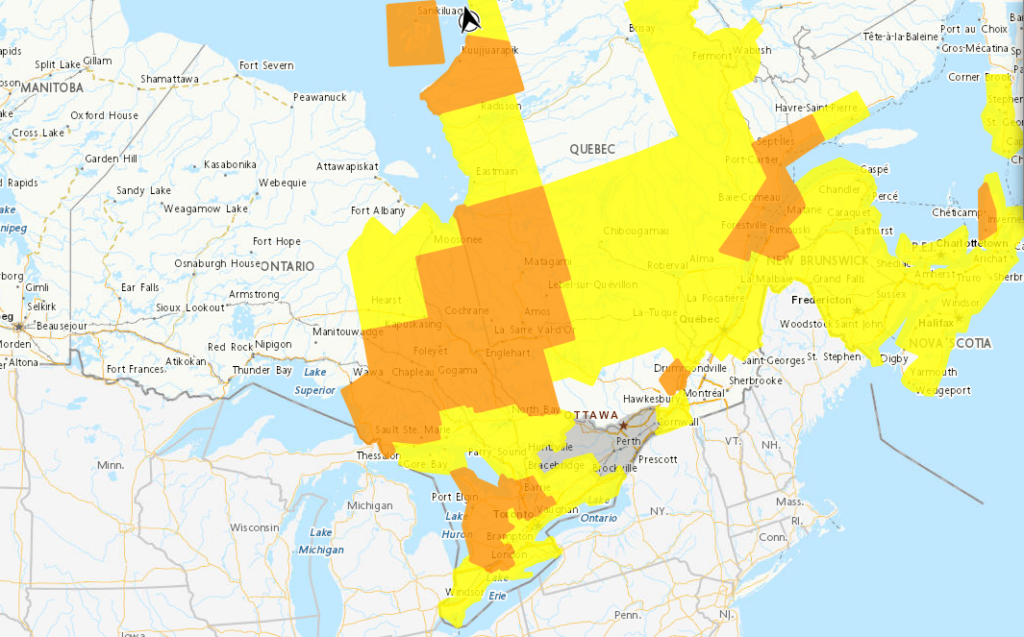

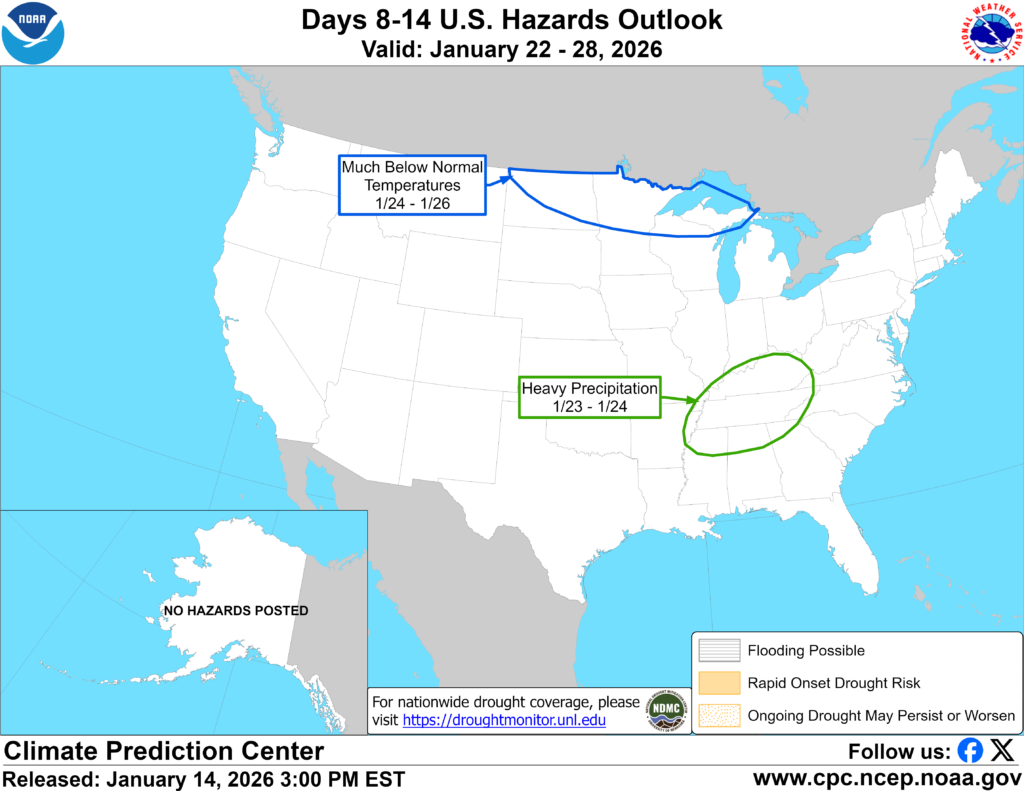

Winter is likely to stick around a bit. While the South may see more variability at times, the Midwest is likely going to see some legitimate cold coming. The CPC has highlighted the Dakotas, Minnesota, the Wisconsin Northwoods, and the U.P. of Michigan for “much below normal” cold Jan 24-26.

The pattern does indeed look healthy for cold, legitimate cold in some places, particularly the Upper Midwest and Great Lakes. Meanwhile, how far east and south will it get? That’s more of an open question. The same 8-to-14-day outlook shows high confidence cold in the North and moderate confidence for more warm weather in the South.

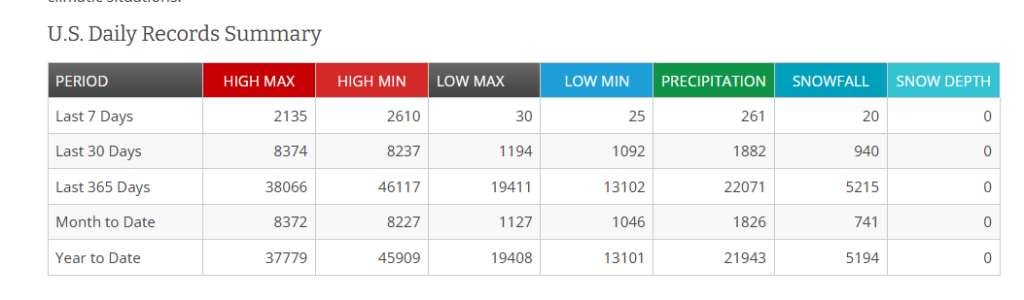

Over the last 30 days, record highs have outpaced record lows by a 29:1 margin (5,210 to 181). Much of that is due to a very warm South and West late last month and a very warm start to 2026 nationally.

The next week or two will erase a good bit of that warmth out of there, but we’ll see if that includes the South.

Windy Plains!

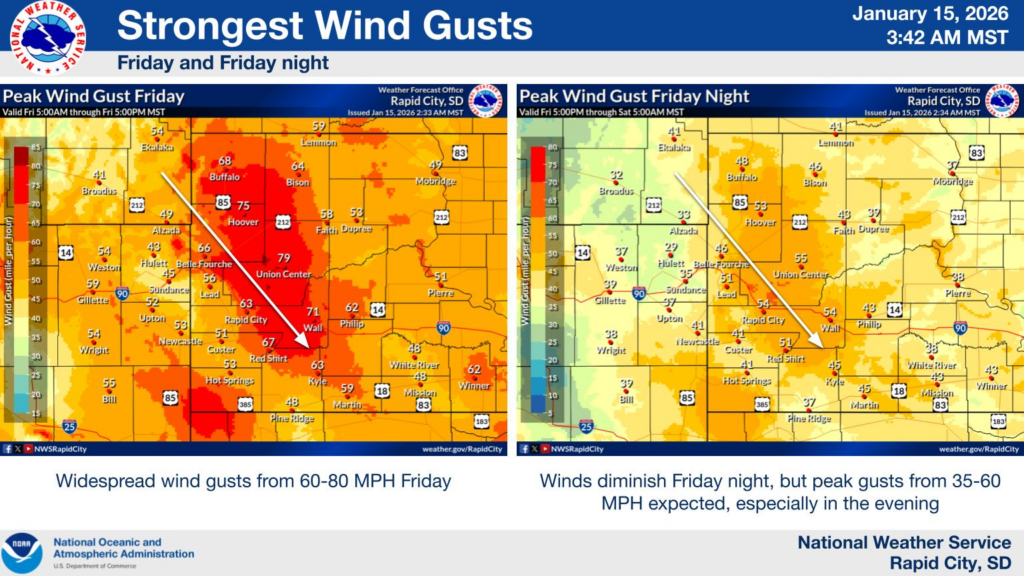

Elsewhere, the main weather story the rest of this week will be winds on Friday in the Plains and northern Rockies, with wind gusts perhaps as high as 75 to 80 mph in parts of South Dakota. This will lead to all sorts of issues in that area, including some higher fire risk.

Winds peak Friday morning.

Slight chance at an Eastern Pacific tropical system?

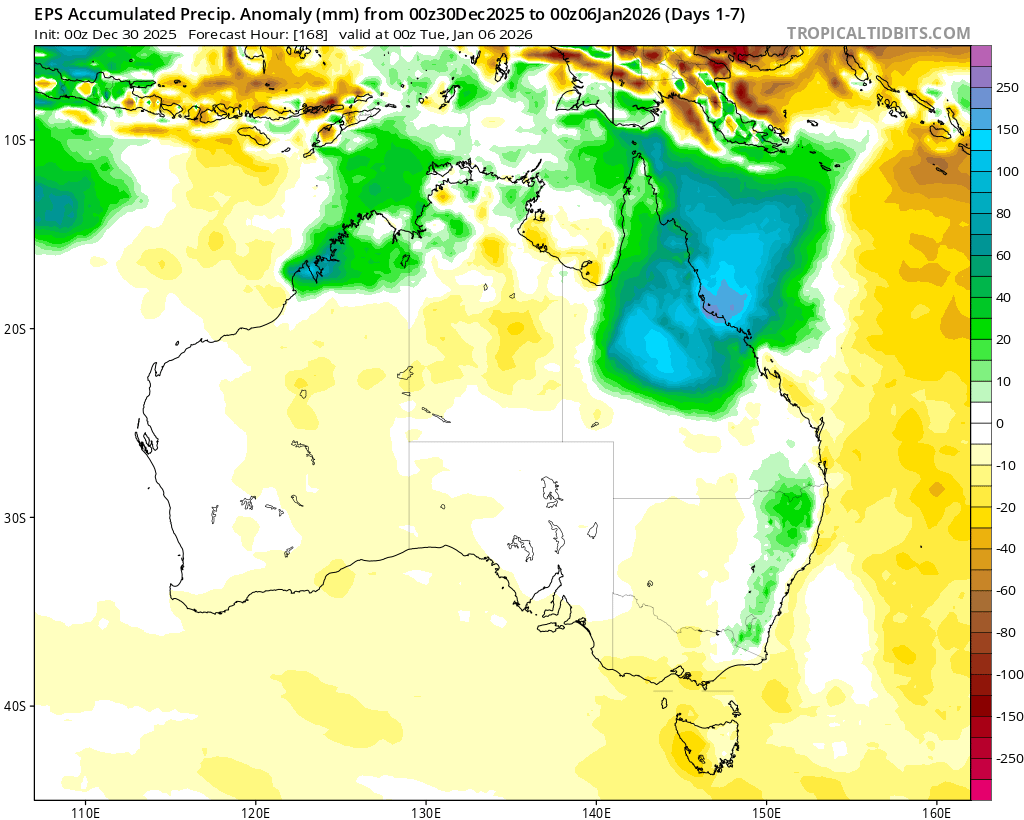

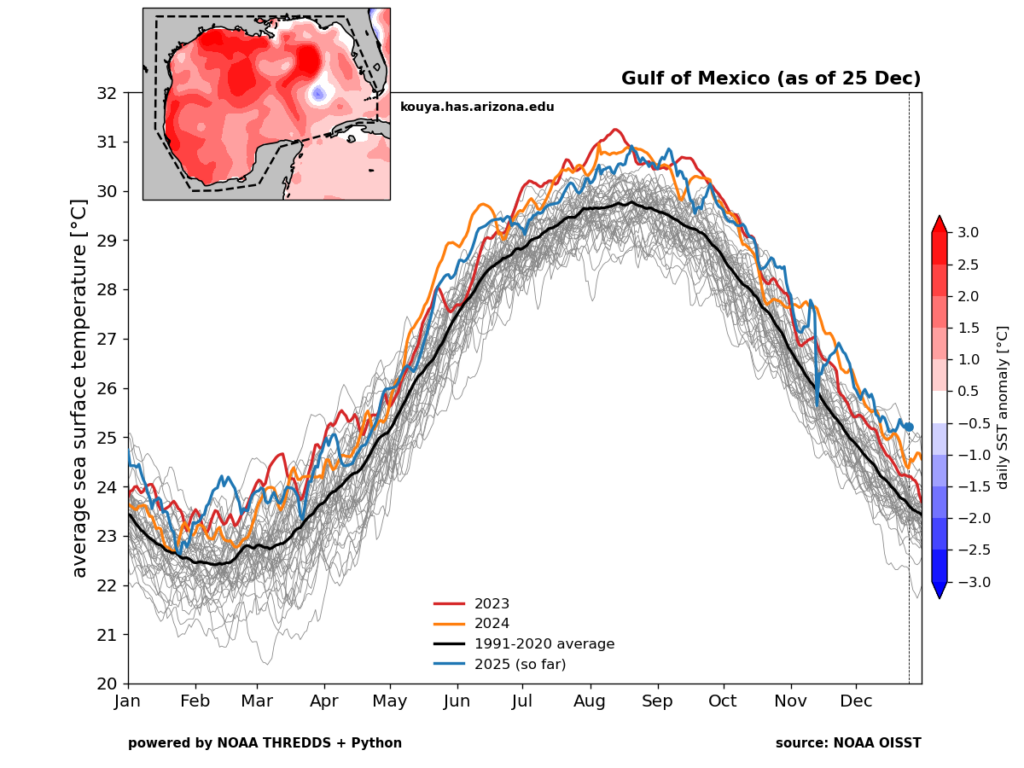

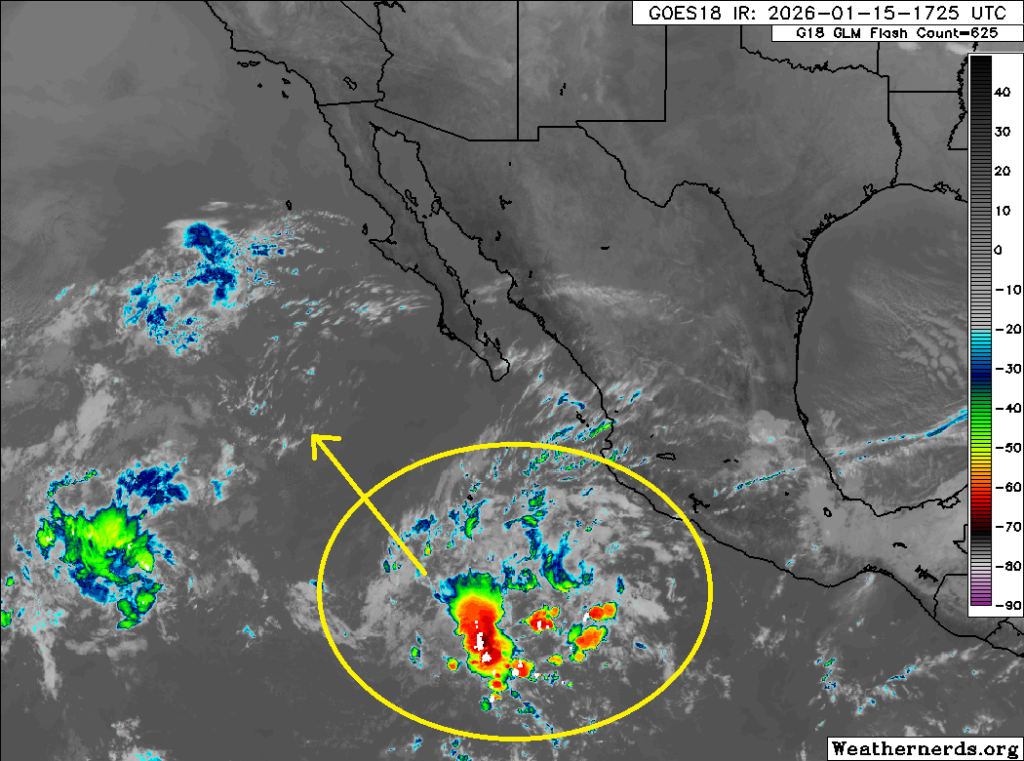

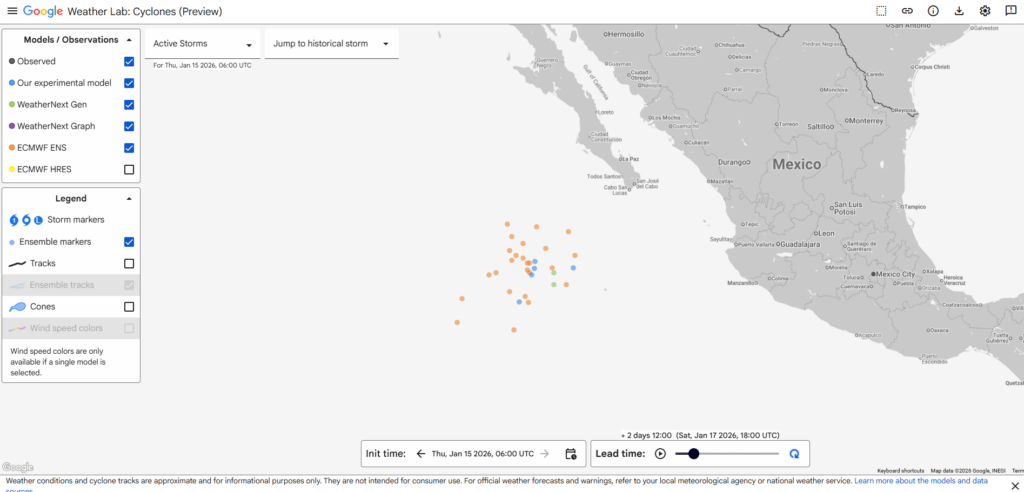

Yes, it’s January. Yes, there may actually be a tropical system in the eastern Pacific. Maybe. If you’ve heard about it, it still seems unlikely, but there is some model support for it.

Modeling suggests that as this drifts northwest, it has at least a very, very slight chance at organizing to a point where it could be a weak depression. Water temperatures in this part of the world are much warmer than normal, which won’t hurt. And yes, Google’s Deep Mind model does show a low chance of this happening too. Support is not great by any means, but there’s enough there there that from a purely meteorological curiosity perspective, this will be interesting to monitor.

The last time we saw a wintertime tropical system in the Central or Eastern Pacific occurred in January of 2016, when Hurricane Pali formed in the Central Pacific, south and west of Hawaii. In the Eastern Pacific, you really need to go back to December of 1983 for this, with Hurricane Winnie that formed south of Mexico, a few hundred miles east of where this disturbance currently is located. Weird? You bet. Not at all normal. In most cases when this happens, it occurs closer to Hawaii or the International Date Line. Another storm in 1922 formed in February somewhere south of here but details are a bit sketchy. Either way, a notable weather item today.