In brief: Today’s post recaps historic cold in Florida this morning and the snowstorm in the Carolinas yesterday. We also take a closer look at the Raleigh-Durham area specifically, which saw relatively little snow compared to the rest of North Carolina and why that happened.

Florida freeze & Carolina snow

Let’s talk first about Florida.

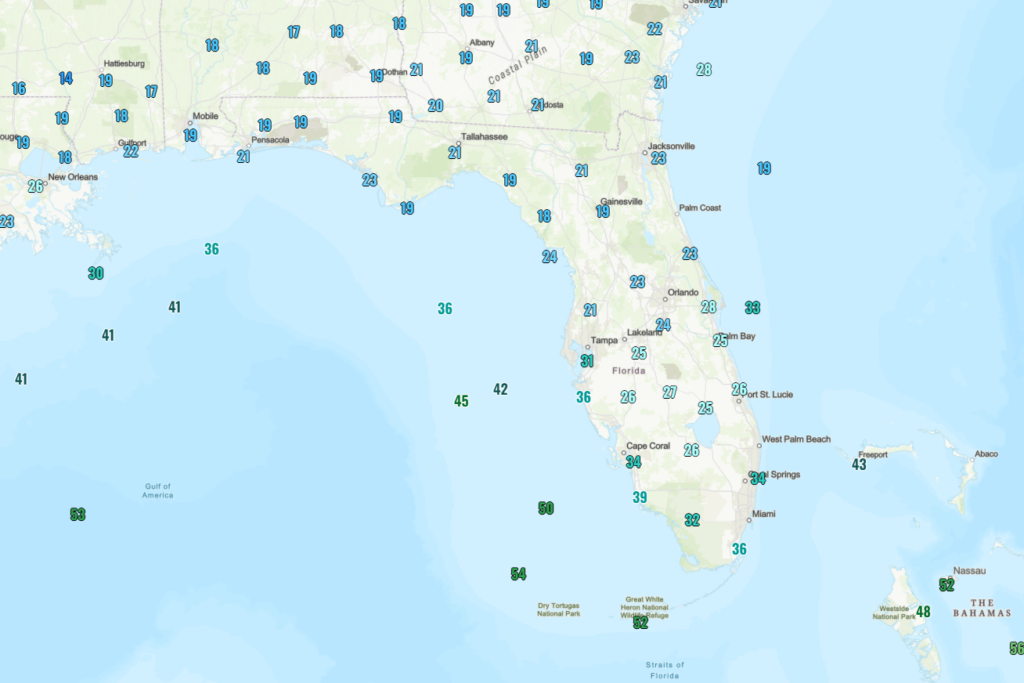

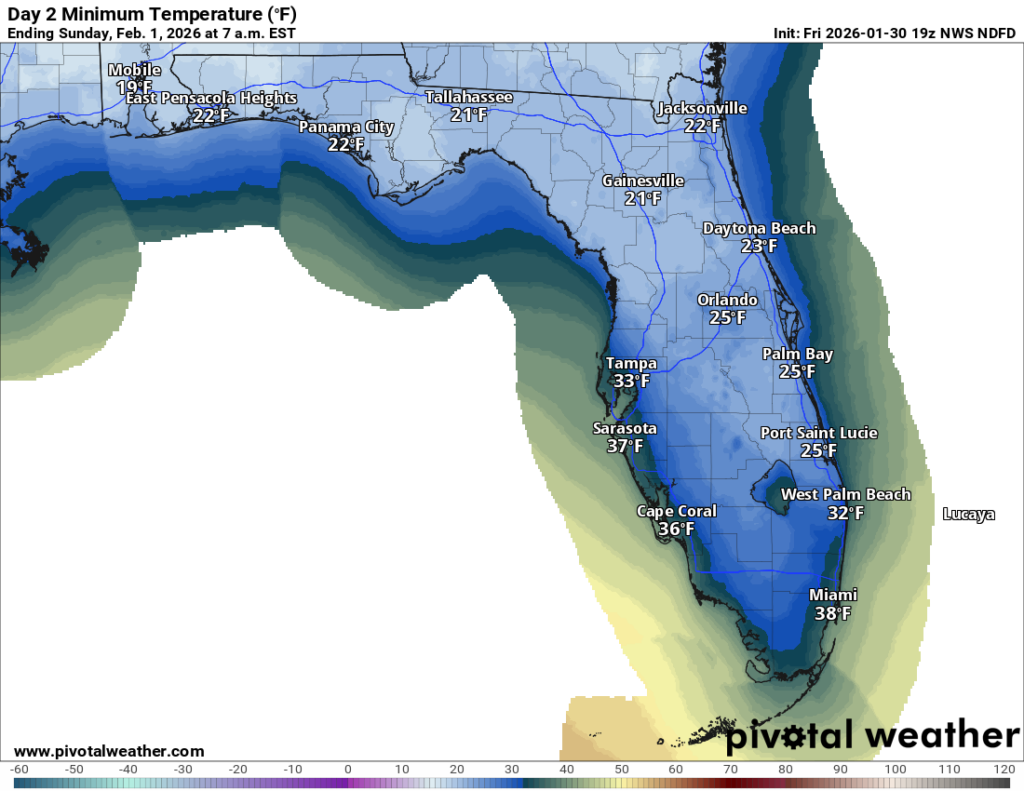

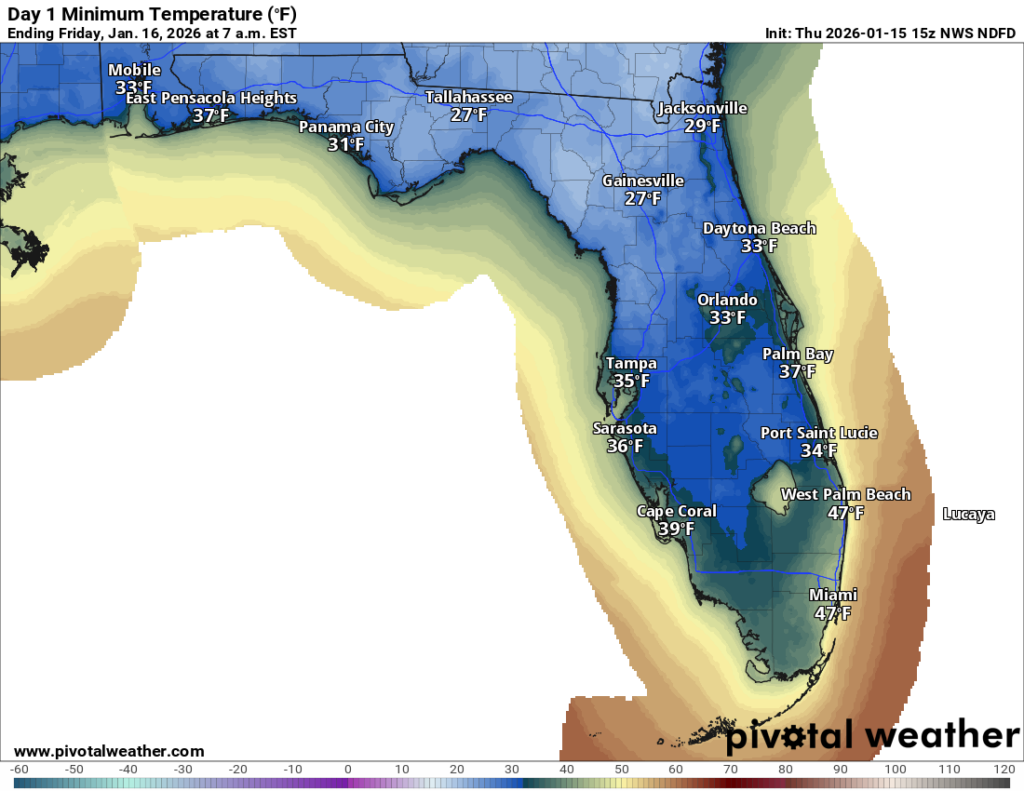

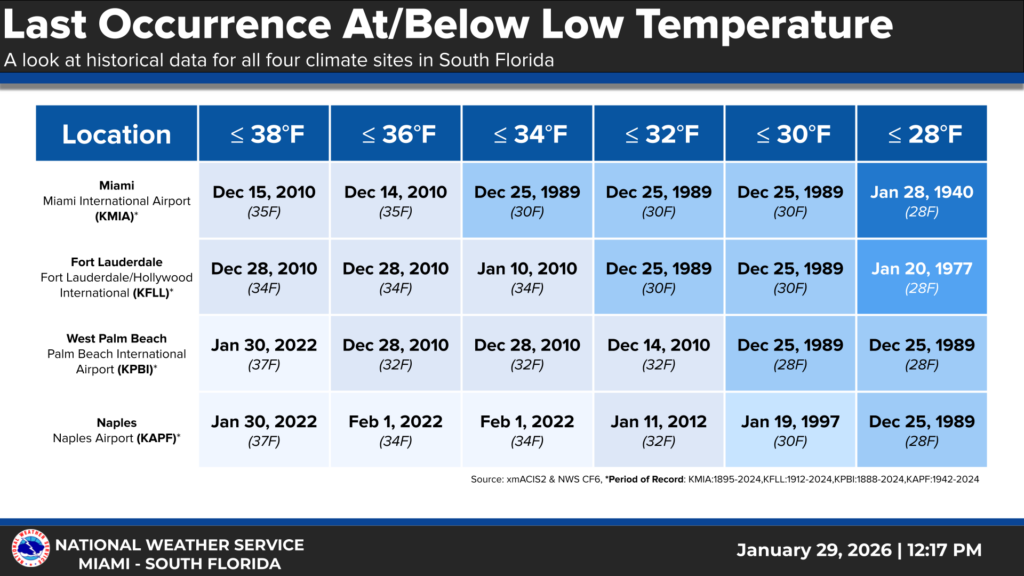

In Jacksonville, the temperature hit 22 degrees for the second time this winter (last seen on January 16th). The wind chill got as cold as 11 degrees there this morning for the first time since January 2014.

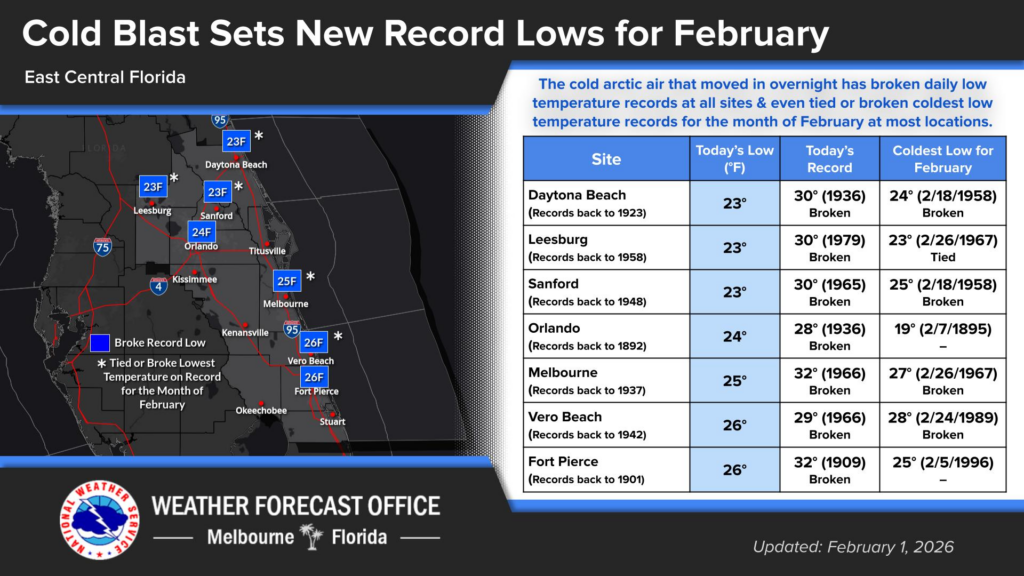

In Orlando, the morning low of 24 degrees was last seen on December 29, 2010 and prior to that Christmas Eve 1989. For Daytona Beach, the 23° morning low was coldest since Christmas 1989. This was also the coldest February morning on record there. Vero Beach and Sanford also had their coldest February mornings back to the 1940s or 1950s as well.

On the Gulf side it was not quite as cold, as Tampa hit 28° (coldest since 2010), Sarasota hit 36° (coldest since 2022), and Fort Myers bottomed out at 34° this morning (coldest since 2018).

The 30° low in West Palm Beach was the coldest since Christmas Day 1989. Wind chills got down to 20° as well.

For Miami, the morning low of 35° was the coldest since January 10, 2010, when they also hit 35 degrees. Prior to 2010, it last happened on January 21, 1985, when it was 34° in Miami. The wind chill of 26 degrees in Miami at 7 AM appears to be the first time that’s happened since the great cold outbreak of Christmas 1989.

For Key West it was only the 5th time in the last 10 years they’ve hit 52° or colder.

Overall, this was a top tier, borderline hall of fame cold outbreak for Florida.

Carolinas snow

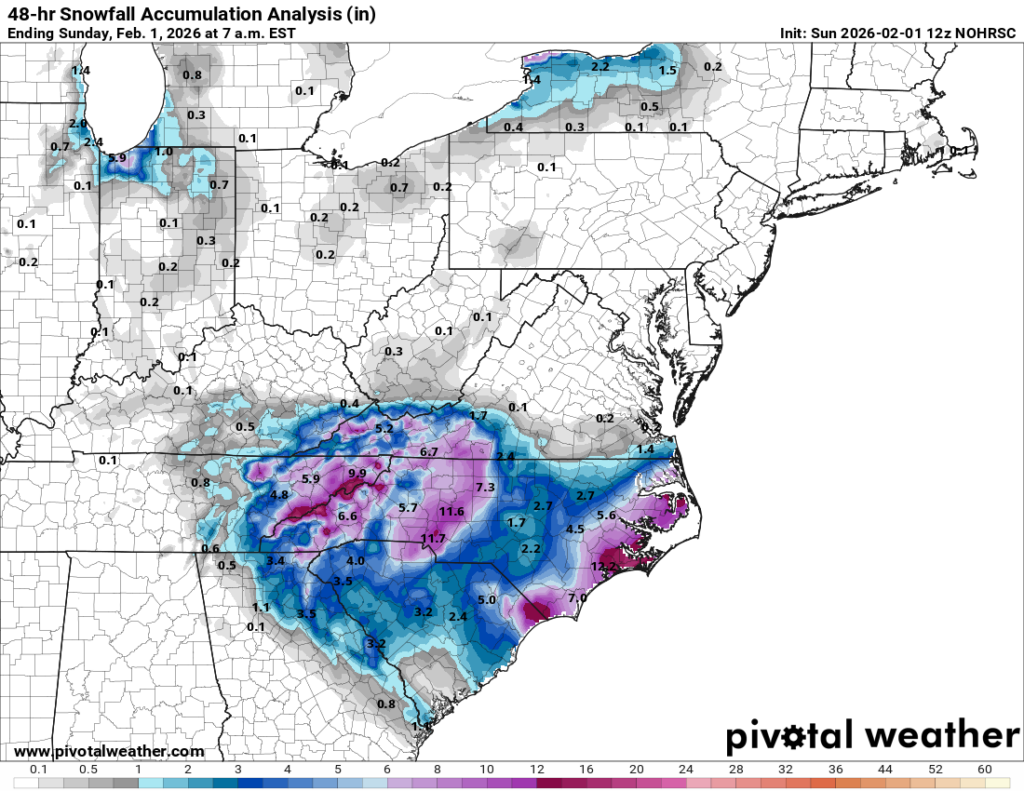

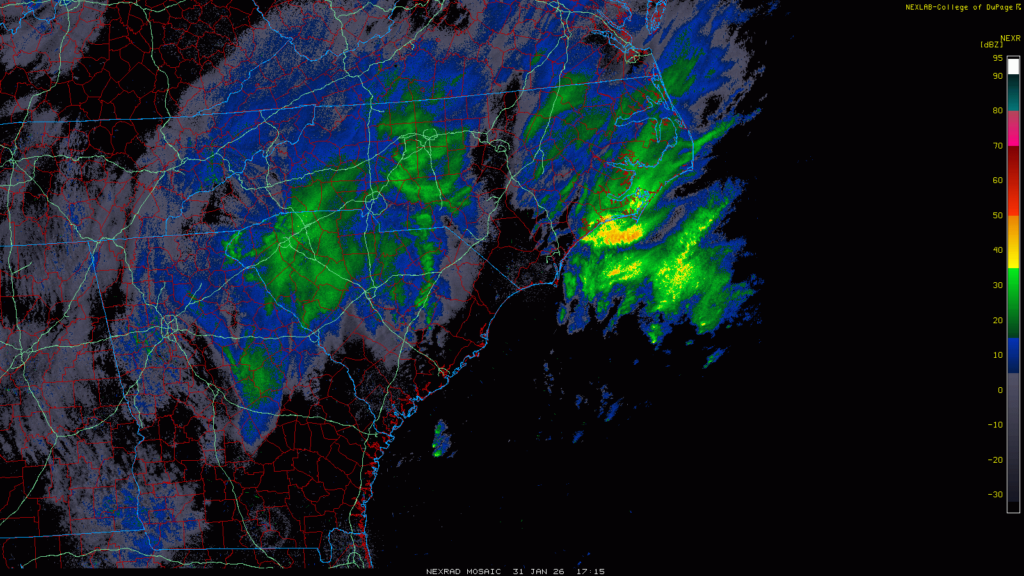

Yesterday’s snowstorm was rather amazing for portions of the Carolinas, with some places seeing historic snow totals.

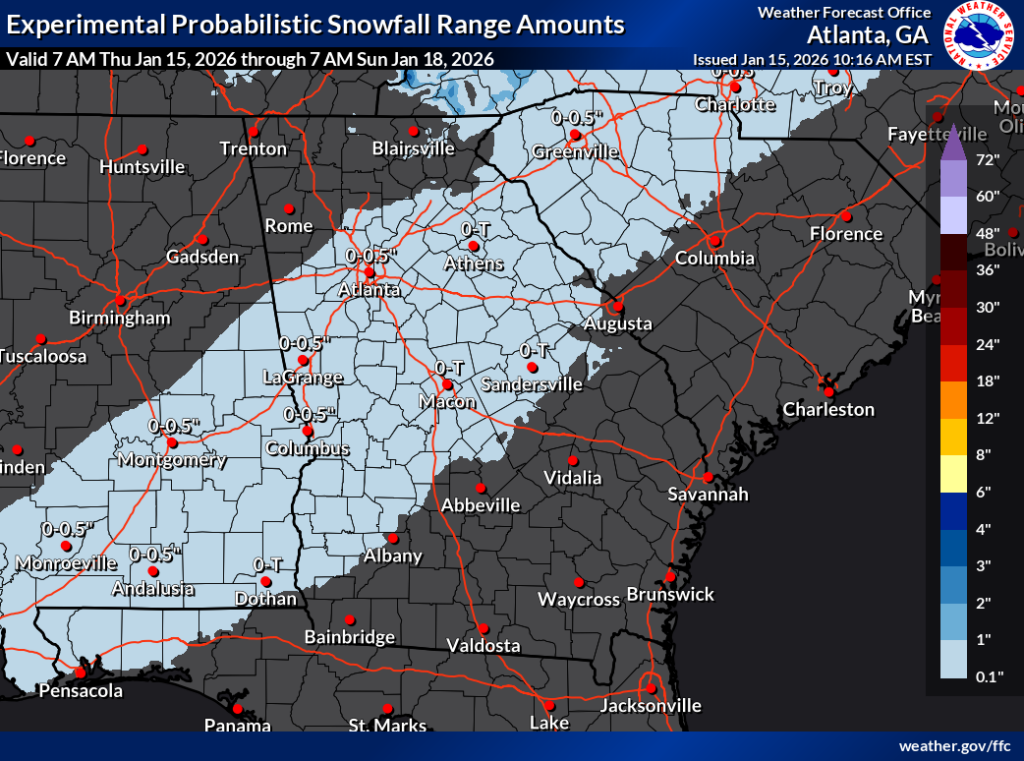

The highest totals I could find were near Faust, NC north of Asheville, where 22.5 inches fell and Peletier, NC, which is just inland from Emerald Isle and just west of Morehead City where 19.5 inches fell. 19 inches was reported near New Bern, NC in Olympia and in Reelsboro, just east of there. It would appear that this is the modern storm of record for portions of southeast North Carolina. New Bern’s previous snowstorm record was 15.5 inches in January 1965. Closer to Wilmington and Myrtle Beach, it was the largest snowstorm since 1989.

Farther inland, Charlotte’s 11.3 inches was the largest snowstorm there since 2004. 10.3 inches was measured in Greensboro, the largest snow there since December 2018.

The RDU snow desert

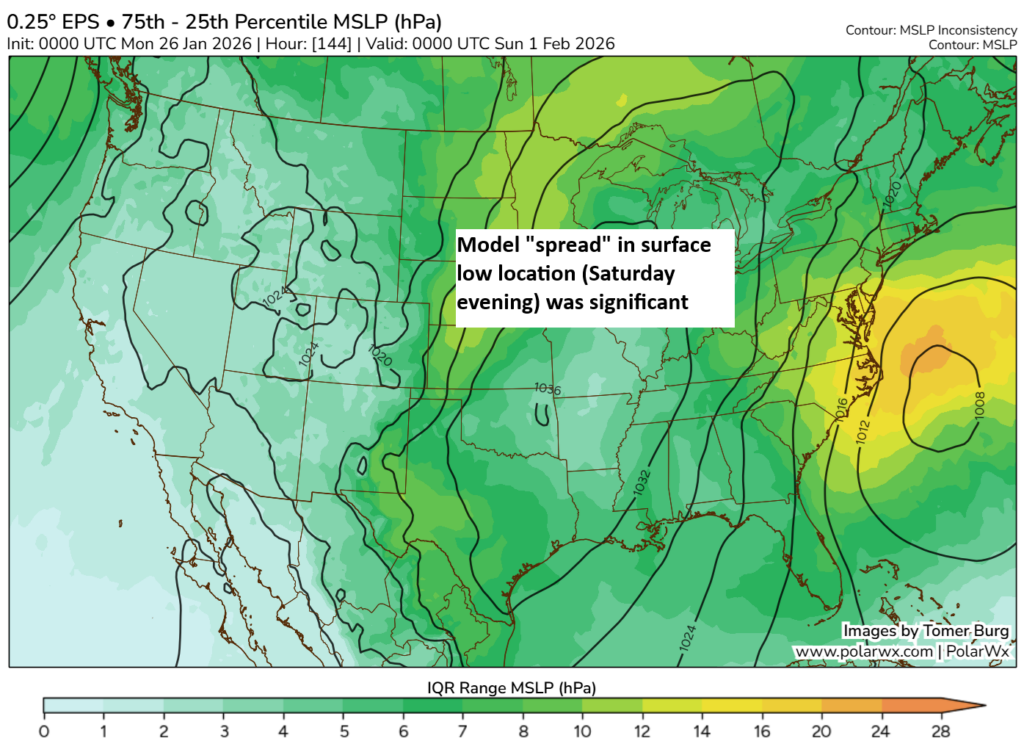

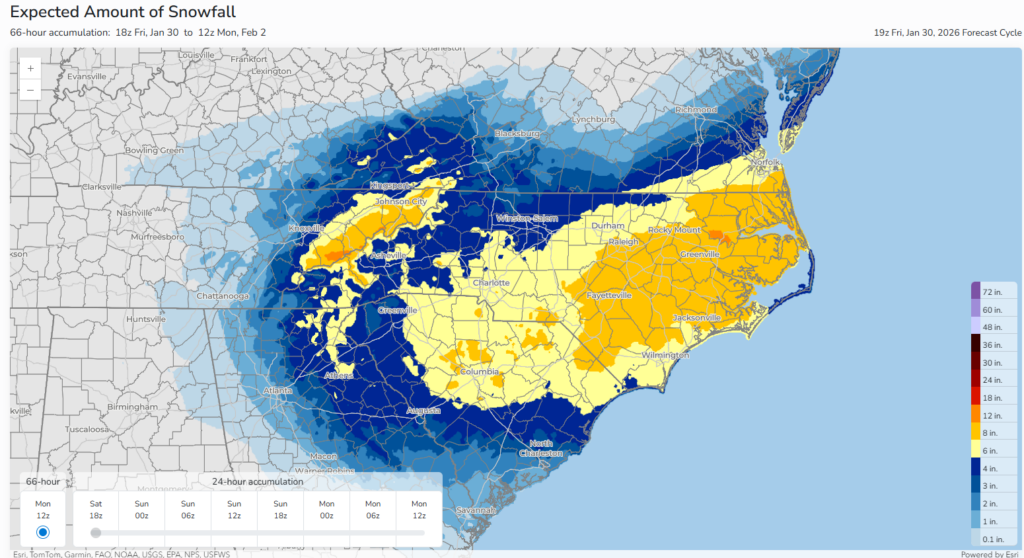

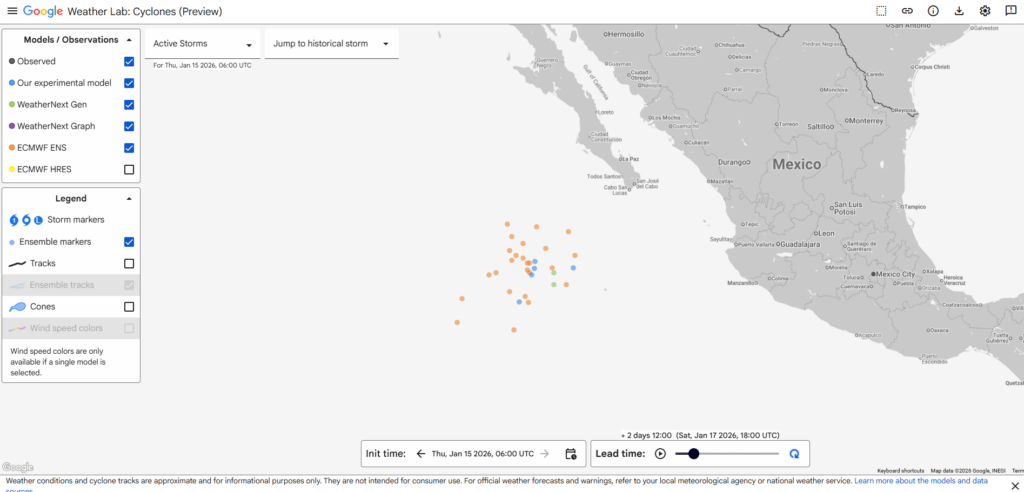

Interestingly, if you look back at the forecasts ahead of the storm, the Raleigh-Durham area was expected to see 8 to 12 inches of snow, roughly. In reality, they ended up closer to 2 to 5 inches. What the heck happened? In snowstorms like this, you often get these significant mesoscale type impacts that take place. In other words, it’s stuff happening at the small scale that causes outsized impacts.

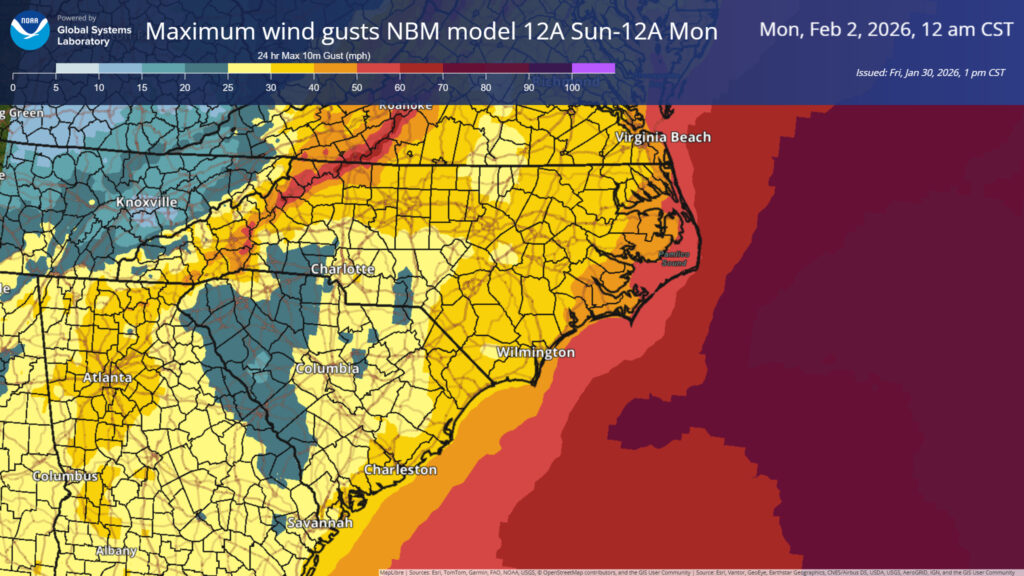

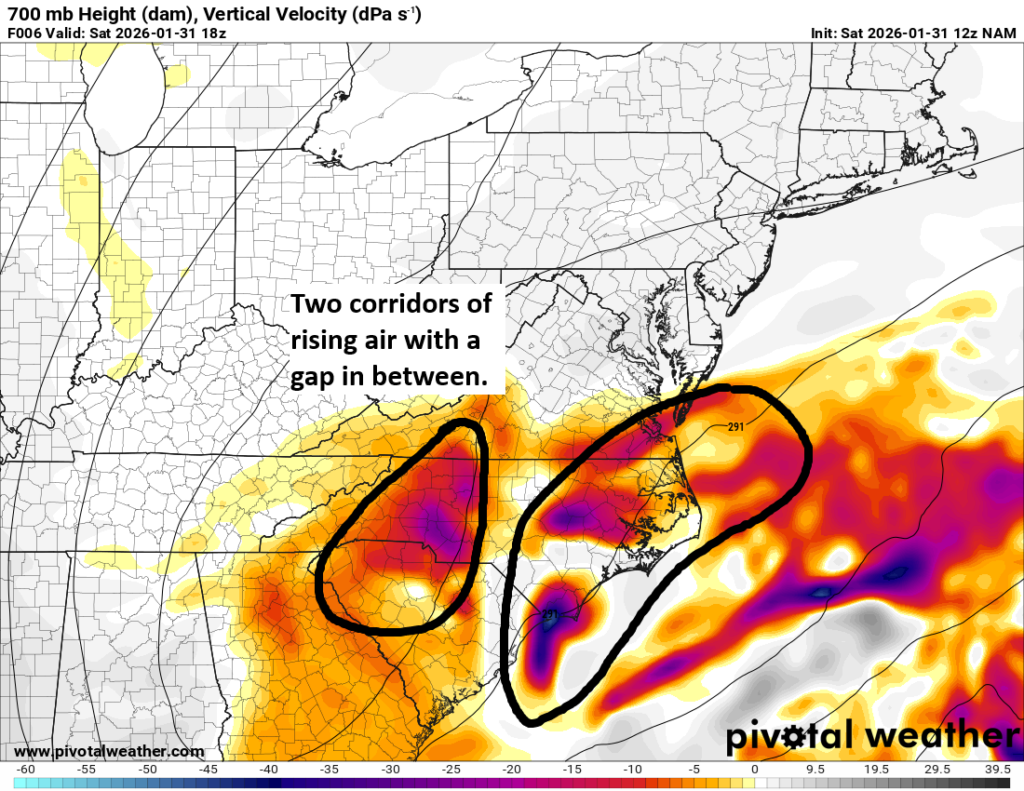

What seems to have happened yesterday is that the Raleigh-Durham area ended up under a band of sinking air, or subsidence, in between two areas of rising air, one inland and one closer to the developing coastal storm itself. As these transitions to coastal storms happen, you’ll occasionally see that happen. This allowed for snow to accumulate more rapidly inland and near the developing storm before the storm blew up and dumped snow on everyone. There were hints of this in the modeling if you squinted hard enough, which is easy to do when you’re analyzing an event after the fact. But there was nothing clear cut that said the RDU area would be snow-deserted for so long. But if you look at the vertical velocity forecast from Saturday’s 12z NAM model, you can indeed see that basically happening.

You aren’t going to look at this and say, “Raleigh is going to get no snow,” but it does at least show a slightly better visual of the potential of a vertical velocity minima/subsidence in the atmosphere that would “gap” an area from seeing heavier snow. It’s not as if this was clearly defined or setup the day before. There were hints of something down toward Fayetteville or the Pee Dee in South Carolina on Friday morning. That shifted closer to the Triad with Friday afternoon’s model guidance. But you aren’t going to look at that alone and sketch a forecast that granular in nature and feel confident. It’s just the challenging nature of these snowstorms.