In brief: Today we explain why the Pacific should be more active than the Atlantic through the next 7 to 10 days and when that could theoretically change. We also talk more about the GFS model’s phantom storm bias.

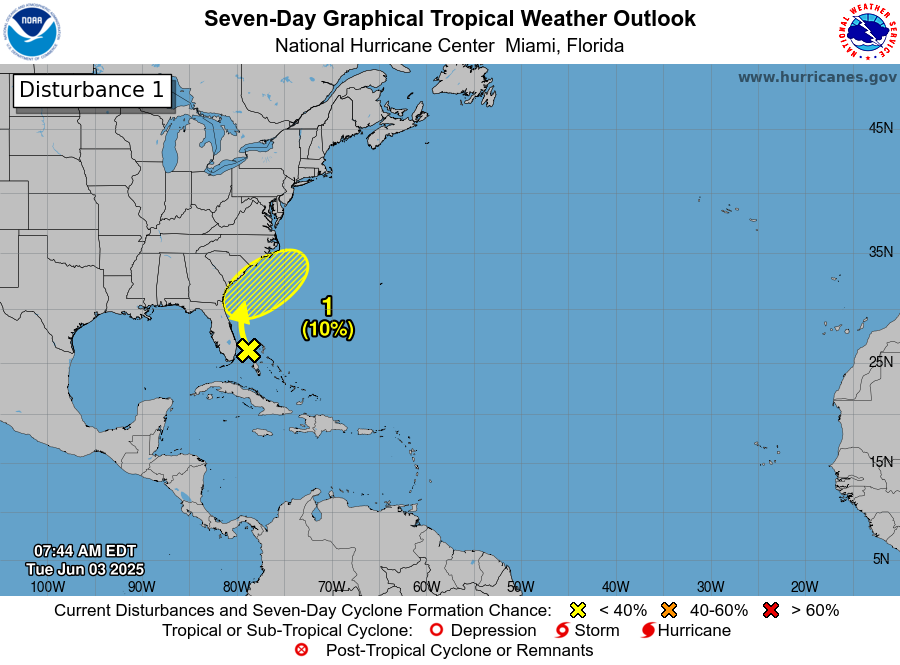

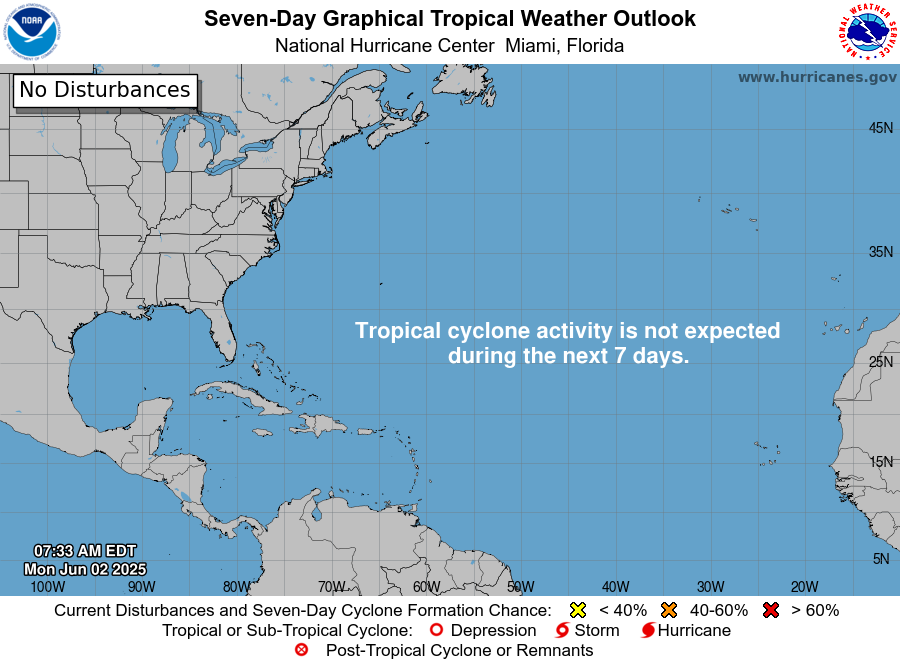

We’ll keep this fairly brief today. The Atlantic is quiet, so I don’t want to go fishing for speculative information. Plenty of other sites do that. That said, we know people want to know how long the generally calm conditions will persist.

Pacific or Atlantic?

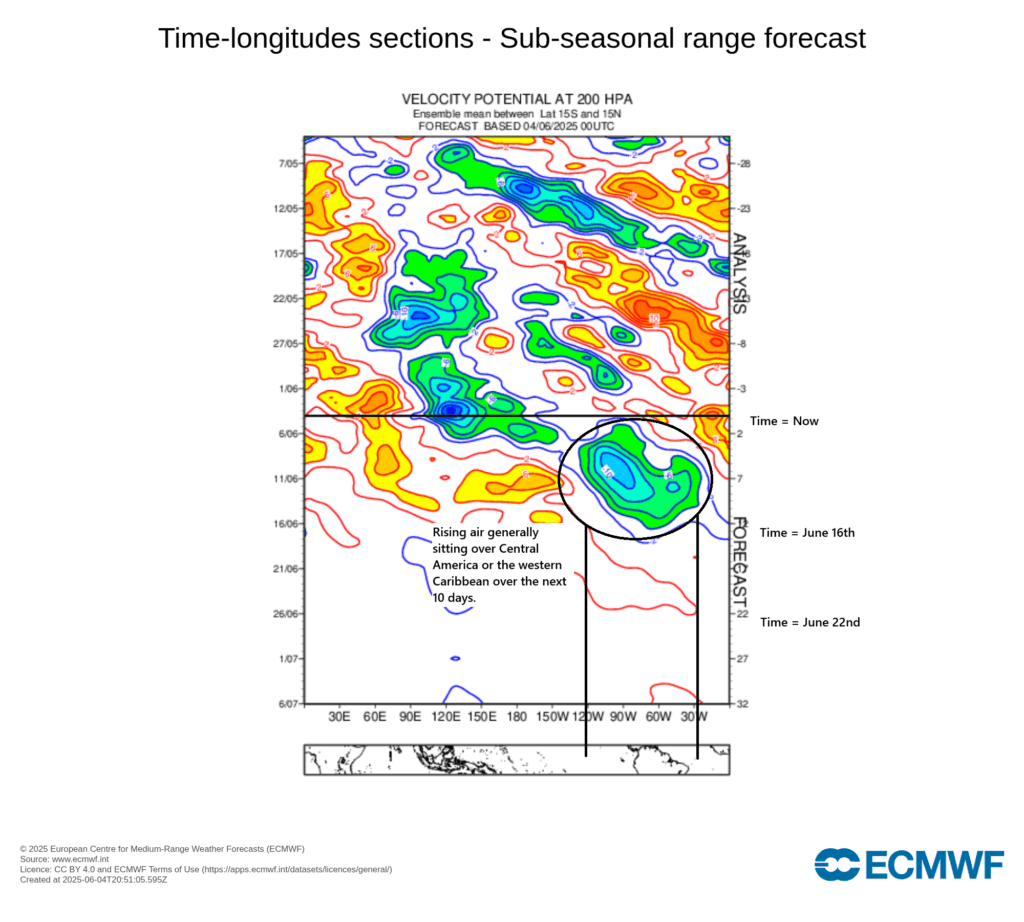

The atmosphere over the eastern Pacific and western Atlantic right now appears to be entering a phase that is indeed favorable for tropical development. If we look at what is called a “Hovmöller” plot, we can identify areas in the tropics that are favorable or unfavorable in terms of where rising air is located.

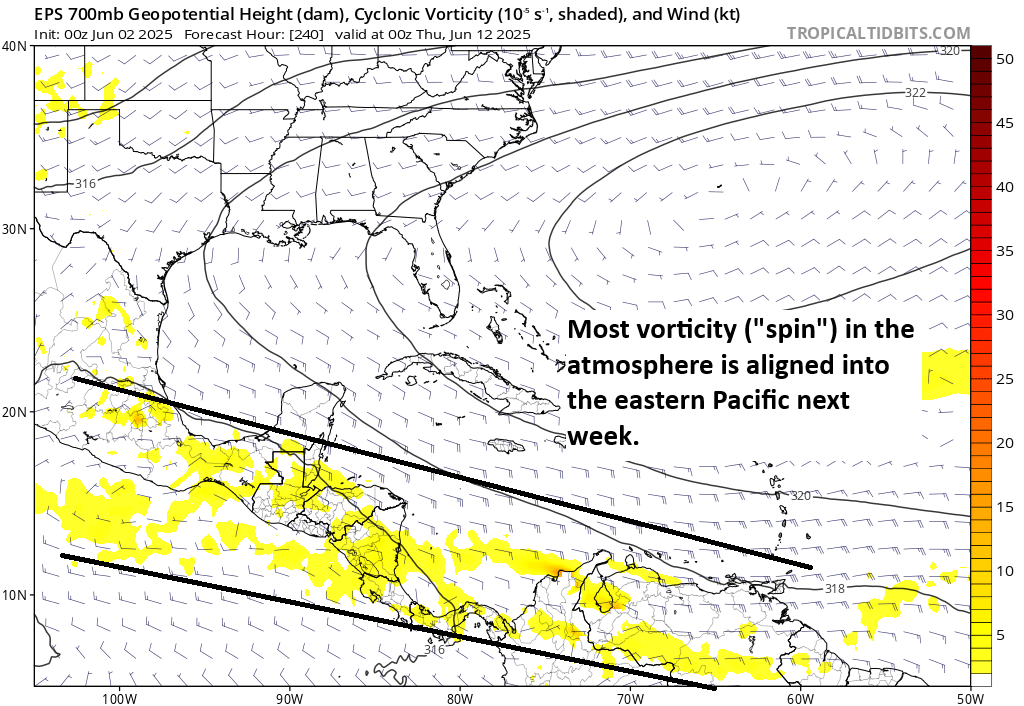

So over the next 10 days, we have an area of rising air, indicated by the blue/green colors above. This is actually showing what we call “divergence” in the upper atmosphere, which typically correlates to “convergence” in the lower atmosphere. For air to rise, you want converging winds. For tropical systems you want rising air. So that’s firmly in place near Central America for the next 10 days.

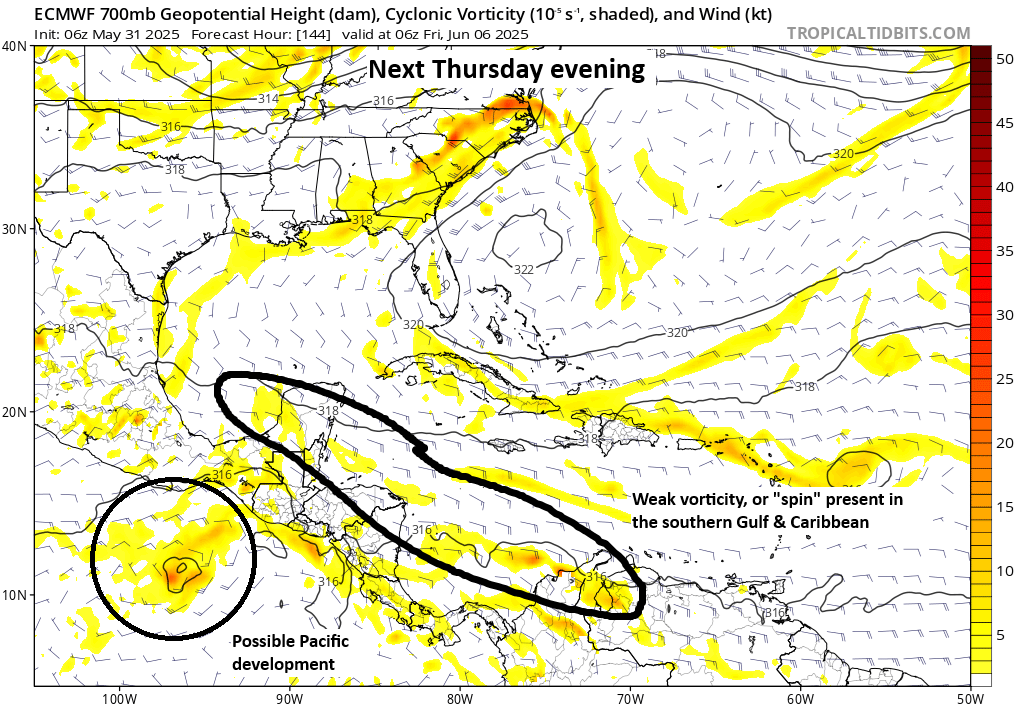

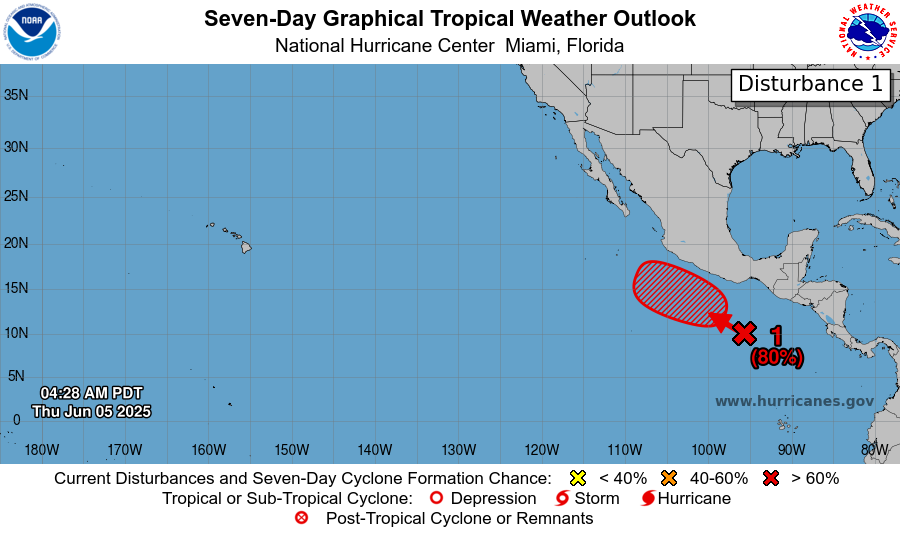

Here’s where the models have actually been somewhat useful. Recall, the GFS model has been going bonkers with a Gulf system almost every day this month and several days last month. But also notice how it’s never advancing in time. It’s always been on like days 10-15. More on that in a second. But if you look under the hood on the GFS and European models, you have also seen a decent signal for Pacific tropical activity.

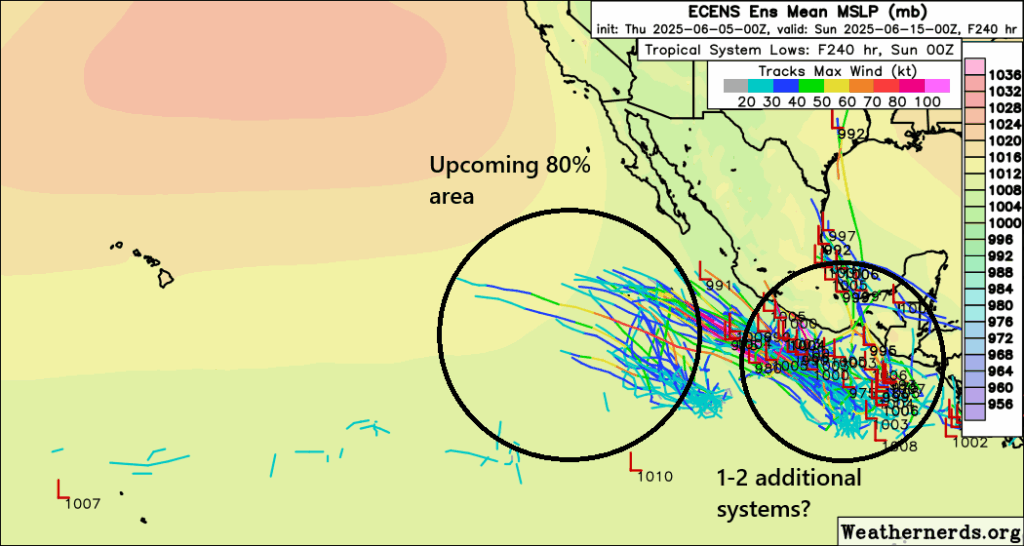

When we look at European model guidance, we can clearly see this Eastern Pacific area that will move out into the Pacific. But we can also see perhaps 1 or 2 other areas by day 10 that may develop close to the Central American or Mexican coast.

Now, the focus is clearly on the Pacific here, but there are elements of interest on this model very close to the east coast of Mexico in the Bay of Campeche. In theory we could see something like that later next week, but the proximity to land would likely hinder its organization significantly.

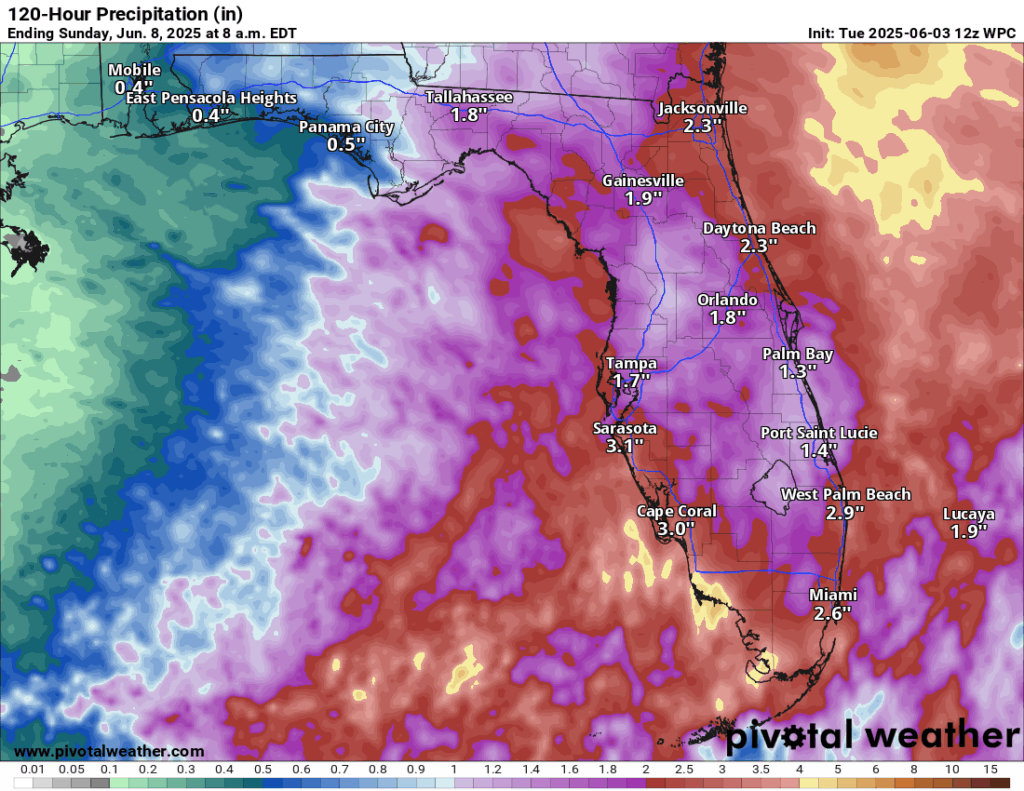

So I think over the next 10 days, while that area of rising air is in place over Central America, the odds will heavily favor Pacific systems over Atlantic ones, though the odds of a Gulf or Caribbean system may begin to increase after the 12th or so. That said, there’s no reliable model guidance showing anything of real concern in the Atlantic over the next 10 to 12 days.

The GFS phantom menace

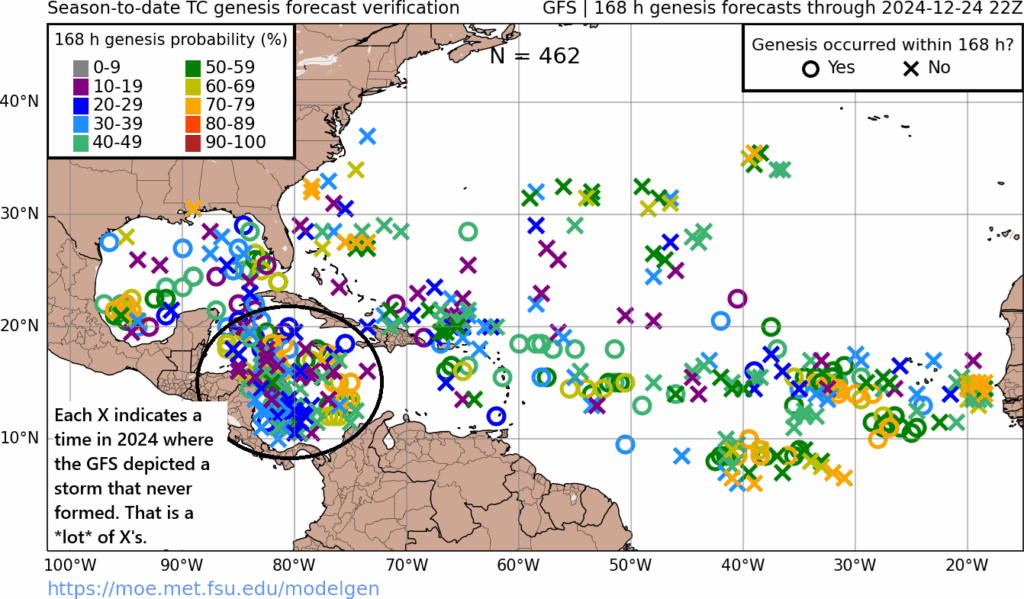

I’m not going to belabor the point about the GFS model, but no matter how often we say it, it still seems people get spooked by this model still showing storms in the Gulf. Again, that is virtually always incorrect. And by virtually always, I cannot recall a major June storm in the Gulf in the last 10 years but I can recall dozens of instances of GFS refrigerator material every single year. In fact, as some others have shown recently, this signal of phantom storms actually stands out in verification metrics.

On the image above, each X indicates a time where the GFS showed something developing last year and it never formed. The majority of the X’s on that map are in the Caribbean (and likely in the early and late season), exactly where the GFS has been showing all the hubbub so far this season. The real tell though is when the storm is perpetually stuck in the day 10 to 15 day purgatory and never advances forward in time. It’s a dead giveaway that this model is up to its old tricks again.

Some people may say the GFS model is useless then, but reality is more nuanced, of course. The model has made improvements in skill over the years, including handling some tropical systems after they’ve formed. But as a forecaster, it’s important to recognize the model bias when you see it, and that’s certainly what we’re seeing right now.