In brief: Invest 92L became Tropical Depression 3 yesterday and is now Tropical Storm Chantal. It’s en route to the Carolinas. We take a detailed look at what occurred in Texas Thursday night and Friday morning.

Note: Most of the data in these posts originates from NOAA and NWS. Many of the taxpayer-funded forecasting tools described below come from NOAA-led research from research institutes that will have their funding eliminated in the current proposed 2026 budget. Access to these tools to inform and protect lives and property would not be possible without NOAA’s work and continuous research efforts.

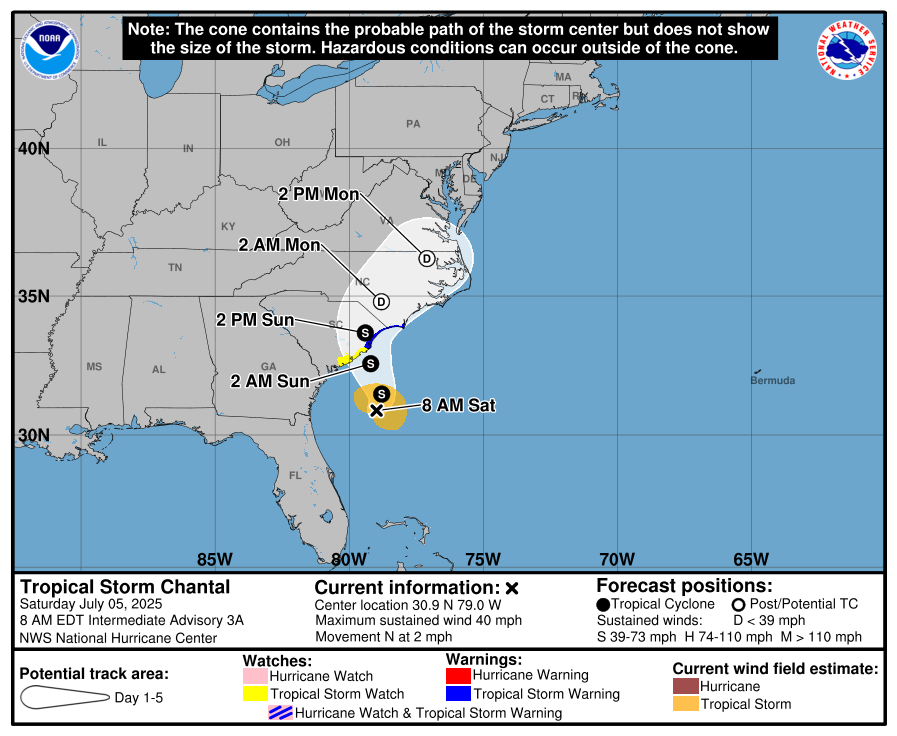

Tropical Storm Chantal

Hot off the presses this morning, Tropical Depression 3 is now Tropical Storm Chantal, giving us a 3 for 3 conversion rate of depressions to storms so far this season.

Chantal’s forecast has not changed a whole heck of a lot since yesterday, as impacts will remain primarily heavy rain and localized flooding, as well as rip currents on the beaches. Please exercise caution, particularly on the Carolina coasts and a little farther north. Chantal will remain over fairly warm water for the next 18 to 24 hours, so it may try to strengthen a bit further. Tropical storm warnings include the upper South Carolina coast, including Myrtle Beach, as well as extreme southeast North Carolina.

Chantal will continue north and east after tomorrow dissipating before it gets to Delmarva.

Unraveling what happened in Texas

First, as someone based in Texas and with multiple members of our large but still close community still missing, I want to extend whatever sort of condolences are possible to friends and family that are dealing with what is truly an unspeakably horrific tragedy. On a holiday weekend that should be celebratory for kids and families no less, in the middle of the night when they’re at their most vulnerable. There truly are no words.

What we can do is take stock of what happened, explain why, explain what was known and what wasn’t know, and try to piece together how something like this happens in 2025.

The cause

As is often the case in interior Texas, one of the culprits involved last night was the remnant of a tropical system. Remember Tropical Storm Barry? It lasted all of 12 hours before coming ashore in Mexico. We can track Barry’s remnants from landfall last weekend through Thursday evening by looking at its “fingerprint” about 10,000 feet above the surface.

So you had the remnants of a tropical storm. Because of this, you had abundant moisture coming from that storm’s source region in the Gulf. You had strong moisture transport coming northward as well with a strong low-level jet stream (a common feature in Texas located about 5,000 feet above the surface). But the jet was oriented to allow for maximum upsloping, aimed right at Hill Country. You had plentiful instability in the atmosphere as well.

So, tallying all that together: A remnant tropical system, moisture levels in the 99th percentile or higher, forced upward motion due to geography and wind direction, and plentiful instability. That’s a recipe for flash flooding. So how do you go from flash flooding to catastrophic flash flooding, because the difference is clearly enormous. When you put those parameters in concert with a weather pattern that allows for maximum efficiency of rainfall, a monsoonal pattern, and slow movement, as well as geography that allows for rapid build up of water on dry ground and riverbeds that “funnel” that through an area, that’s when you flip from ordinary to potentially tragic.

The forecast

Beginning last Sunday morning, forecast discussions from the NWS office in San Antonio and Austin noted the potential for heavy rain through the week. By Monday morning, they also noted the potential for nighttime warm rain processes in the western part of their coverage area, which would probably include Kerrville. By Tuesday afternoon they had specifically mentioned the potential for flooding on Thursday. Nothing really changed messaging wise on Wednesday or Thursday morning. By the afternoon, flood watches had been hoisted as the potential for significant rain became more evident.

Modeling? Well, it was so-so. When it comes to heavy rain, the lower resolution global models can give you a sense of what may happen, but they’re generally unable to resolve where the heaviest rains will fall. I went back and looked at some of the model rainfall forecasts for the event this past week. While some of the global models did indicate heavy rainfall potential, none were really flagging a high-risk type event. Even on Thursday morning, the WPC Excessive Rain Outlook showed a slight risk (2/4) in the area. We could probably say that the catastrophic rains were isolated enough that this was still reasonable. But truth be told, this probably deserved a moderate.

Within their discussion, they did emphasize risks of 3 inches or more, which is a reasonable note to make.

The higher resolution models did do better and did lead everyone down the correct path. On Wednesday night, the 00z HRRR model had about 7-9″ in a few bullseyes between Mexico and Texas by Friday morning. By Thursday morning, the model showed as much as 10 to 13 inches in parts of Texas. By Thursday evening, that was as much as 20 inches. So the HRRR model upped the ante all day.

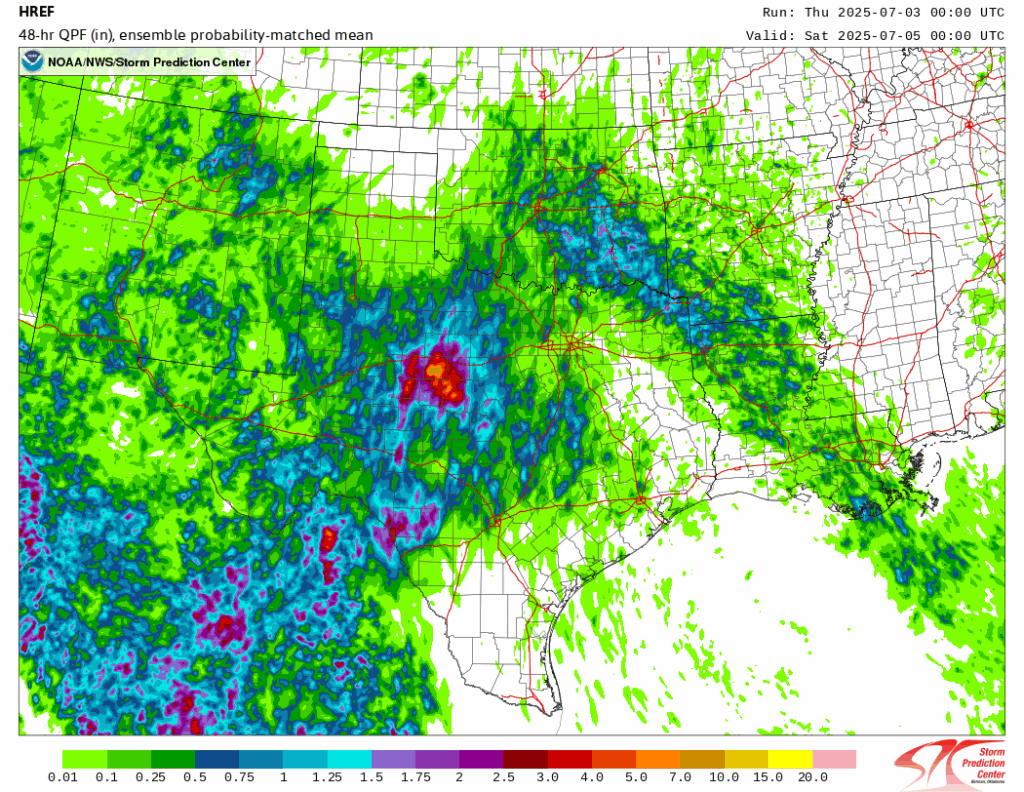

The HREF model on Thursday morning, a tool developed from NOAA research also indicated the risk of 10″ or more in spots, using the “probability matched mean” product which can identify higher risk areas for heavy rainfall. I’ve used this in Houston many times, often with considerable forecast success ahead of flooding events. It has a knack for cutting through some of these higher end events and highlighting those risks.

So the signals were there and got worse as Thursday progressed. Messaging and flood watches responded to this appropriately and expanded into Thursday evening.

The warnings

Flash flood warnings were issued for areas before midnight as radar rain totals began to inflate up and over 3 to 4 inches. A flash flood emergency was issued at 4 AM for the Kerrville storms and 4:15 AM for storms near San Angelo. Rain totals were estimated to be encroaching on 10 inches at that point. So there was warning. This NWS office is acutely aware of the threats to the area from flooding, and the history is there. So I am assuming they were timely warnings unless I hear otherwise.

Issuing the warning is half the process. Were the warnings received and acted on? That’s another story. And that will also come out in the days ahead. More on that below.

Did budget cuts play a role?

No. In this particular case, we have seen absolutely nothing to suggest that current staffing or budget issues within NOAA and the NWS played any role at all in this event. Anyone using this event to claim that is being dishonest. There are many places you can go with expressing thoughts on the current and proposed cuts. We’ve been very vocal about them here. But this is not the right event for those takes.

In fact, weather balloon launches played a vital role in forecast messaging on Thursday night as the event was beginning to unfold. If you want to go that route, use this event as a symbol of the value NOAA and NWS bring to society, understanding that as horrific as this is, yes, it could always have been even worse.

What should we be asking about then?

Beyond the fact that this was truly a tragedy that is extremely difficult to disseminate warnings on, I think we need to focus our attention on how people in these types of locations receive warnings. This seems to be where the breakdown occurred.

It’s not as if catastrophic flash flooding is new in interior Texas. There are literal books written about the history. The region is actually referred to as “Flash Flood Alley.” But how we manage that risk is crucially important context here. Are there sirens in place? Do there need to be sirens in place? Would people even hear sirens in the middle of the night in cabins or RVs or wherever they were? Tornado sirens have traditionally been used in parts of the country for people outdoors to get warnings. Is that an appropriate method in this region for the middle of the night and indoors?

Do we need to start thinking of every risk of flooding in Texas as a potential high-end event we should pre-evacuate the highest risk people (like children and elderly in floodways) for? Is that even practical? We can critique the answer given by the Kerr County judge here all day, but he’s correct in that the reality is they deal with flooding a lot. What is actually practical? I don’t know the answers to these questions. But it’s been a little over 10 years since Wimberley, which was a wake up call in some ways too. It’s time for another, and we need to think much bigger than just the areas impacted this time and more about Flash Flood Alley as a whole. Flooding risk is high in Texas. People learn to live with it in some ways. But something like this absolutely cannot happen again. The Texas legislature meets for a special session beginning on July 21st. This may be an important topic to add to the agenda.

Thank you for this very informative post and explanation. There will be so much finger pointing and blame, when in reality, there will always be events out of our control. Thank you for all you do.

Excellent analysis, Eric. Water levels were jumping 5 feet every 15 minutes from what I’ve seen. We’re here at Canyon Lake. Thank heavens it can absorb this much water and not threaten flooding for the folks downstream. Praying for all.

Well, you spoke too soon. Us down south of the dam got about 10 inches in an hour and a half today. However, Comal County has an effective warning system and procedures in place to get everyone out before it’s too late.

Thank you for helping us understand the science behind this awful tragedy.

Thank you Matt for your excellent thoughts and detailed analysis on this event. I so appreciate your explanations!

Well written. Objective. Focused on facts. Remember, without the right questions there can be no right answers. A fine balance between keeping human mentality in fear without inducing too much fright that the mind cares not to think about outcomes. Would regular practice at flood evacuation have helped? They do in schools for fire drills. With NOAA and NWS, cell service, GPS and satellites these tragedies are inexcusable.

To execute a fire (non) drill, you need a fire/smoke alarm to alert you in advance of the entire building being engulfed. Without a flood warning system, doing evacuation drills to practice would be useless if you can’t execute it in a real emergency until you’re already floating down the river inside a building.

Excellent analysis, as always, Matt. You asked the right question: How do we get decision-makers in these Flash Flood prone areas to follow – hour-by-hour – the critical updates being issued by the SPC and NWS? Even of more importance, how do we get these key decision makers to HEED THESE WARNINGS? It’s not a matter of yelling “Fire!” in a movie theater; it’s a matter of putting the lives of people first, and responding immediately to the warnings from reliable and reputable local NWS Forecast Offices. Bless you for this article – absolutely on target.

– Sid Sperry

Matt, would the remnants of Barry account for recent rains and high river levels in the Rio Grande near the Big Bend?

Excellent article. . Please keep up the good work. It helps us understand what went wrong and some solutions for the future. All we can do with weather is be prepared.

Please note: The flash flood emergency warnings did NOT give people time to evacuate. The rain was a deluge within 1 hour of the emergency, in all affected areas. Totally dangerous to have people evacuating with that kind of notice, especially on roads with LOTS of low-water crossings. Sounds like no one was reading the HRRR model; that’s what gave the proper notice.

Thank you so much for this analysis; as a former Houstonian and now West Texan, this is what I was waiting for. I’m really troubled about how we forecast the interactions of tropical systems with existing topography and weather conditions. Helene in NC really made me think about this, and now TS Barry.

Well said. It is terrifying to think that with all the low water crossings, that by the time there’s a flash flood emergency, there pretty much is no escape in some of these floods prone areas.

As a former Austinite now living in Aggieland, I, too needed this analysis. Matt, thank you for your excellent explanation of what otherwise feels incomprehensible.

Between Helene and Barry we clearly need a lot more research into the interaction of extreme rainfall and hilly/mountainous terrain. Sadly, funding cuts to NOAA make this unlikely.

The warning came 3 hours too late. With a siren system, they could have fled on foot directly uphill away from the river and then waited it out. That’s exactly what is done south of Canyon Dam when tubers have to quickly get out of the water due to a flash flood.

Why don’t river gauges have alarms associated with them?

The USGS has Water Alert (https://accounts.waterdata.usgs.gov/wateralert/) where you CAN setup alerts for stream gages.

See my second point above.

There exist alerts you may sign up for on the USGS website…

That’s only helpful if you’re in an area with reliable cell service. Many areas of Kerrville are in Canyon valleys with little to no cell service.

Kerr County has refused to fund sirens.

The river gauges in Kerr County are so poorly maintained that they frequently fail to transmit accurate data during flash floods. The warning system needs to be based on rainfall rate and location, not streamflow data (by the time you have the streamflow data, it’s already too late).

Great work

Thanks for this. As someone who used to advocate for a living, may I suggest that you provide some tools to help your readers advocate for NOAA funding? A sample letter or script for writing or calling our congresspeople, A link to addresses and phone numbers for members of Congress, etc.

It seems appropriate to conclude that even after staffing changes and cuts, that warnings were still sent – and those folk are heroes, making do in very difficult circumstances. But I suspect it’s still a factor, that when you sow chaos in an organization and take out the people who have all kinds of experience and informal networks, that this costs hours in getting the warnings across and out to the right people. We heard that cell phones didn’t get an alert – is this normally the role of the NWS office or is it local sheriffs etc? How much loss of life do we avert because of “Oh, I have the sheriff’s cell, I’m calling him right now” and how much of the process, documented or not, of getting those alerts to the last mile has been gutted? I suspect more than we realize.

A lot of the people who worked in organizations like this are amazing and flexible problem solvers who have levers to pull aside from just issuing a text warning on the NWS site at 4 am and know when to pull them. When they’re pulled out with no succession planning a lot of institutional knowledge is lost.

I grew up in Tulsa where sirens went off every Friday at noon as a test. In a storm, we had learned to listen for sirens, and if one went off we knew to take cover. Perhaps sirens would have helped in this tragedy.

The Wall Street Journal has been reporting 12” of rain fell in an hour. Can this be correct?

There were a few areas that got rates of 7.2 inches per hour (in Seguin, TX this afternoon). That’s the highest I saw, and I’ve been glued to the weather today. A portion of Kerr County got 12 inches in about a 3 hour period, though. Menard County had about 18 inches in the same timeframe. There might have been a radar indicated 12 inch per hour, but I doubt that actually fell anywhere it could be officially verified.

Copy

Comal and Guadalupe Counties have had effective flood siren systems that are LOUD (they will wake you up indoors). They have been in service for over 25 years. Today, 10 inches of rain fell below Canyon Dam and the sirens sounded to evacuate campers before the river rise even registered on flood gauges. Guadalupe County has sirens, AND a reverse 911 system that will text, email, and call every 5 minutes over and over until you acknowledge you received the message. Johnson County installed a system after the 2015 Wimberley flood. The city of Austin has an extensive warning system. I live in New Braunfels on the Guadalupe County side of town, and I received repetitive warnings outside of NWS alerts. That system is effective. Having NOTHING when you’re 30 miles from the headwaters of the Guadalupe River and it’s completely uncontrolled is just plain ineptness, or stupidity, or both, or worse.

This is the third time Kerr County has allowed children to drown in floods because they refuse to install ANY wanting system at all. The NWS said 2-4 inches of rain were falling upstream of Kerrville at around 2am. Comal County’s sirens have rain gauges on them, so they can activate based on rainfall, not streamflow data. Kerr County had two floods prior to 2025 the take lessons from, and the took NO lessons. Kerr County utterly failed to maintain public safety, and then said they didn’t know it was going to flood. The entire county commission and judge should resign immediately. The failure to install ANY warning system at all after Wimberley in 2015, Kerrville in 1987, Kerrville in 2002, New Braunfels in 1998, etc, is beyond negligence. It’s criminal without a law to enforce the criminality of it, period. The leadership of Kerr County should be ashamed of themselves.

Speaking of the NWS New Braunfels office, they did not issue the flash flood emergency PDS alert until 7:24am, 3 hours after the flood wave was already washing houses down stream in Kerrville. They may have issued a regular flash flood warning around 4am, but if they already knew 2-4 inches of rain was falling in the hills upstream of Kerrville at 2am, it was an emergency PDS by 4am whether or not the river gauges reflected that. I believe the ball was dropped on the NWS sending the PDS alert. I have a NOAA weather radio. I got a warning tone at 2am for a flash flood warning in Bandera County between 2am and 3am, and the next one wasn’t until 7:24 for Kerr County with the PDS tag. Something doesn’t add up, there.

Excuse typos, this post was created while enraged with anger of the breakdown in public safety this weekend.

As an architect, sleeping below the flood elevation is a non-starter. It’s irresponsible, especially with children.

That’s a whole other investigation that’s going to occur. There are murmurs in the construction circles that many of the buildings at those camps did not have the property flood plain development permits to be located where they were in the first place. If Kerr County knew and looked the other way, Kerr County is in violation of federal law regulating the National Flood Insurance Program. If it turns out to be true, Kerr County is at risk of losing membership all together in the NFIP, and EVERYONE in that county will no longer be able to purchase government based flood insurance. So, that’s a whole separate but just as relevant investigation that ought to be done by someone outside the county.

“ If you want to go that route, use this event as a symbol of the value NOAA and NWS bring to society, understanding that as horrific as this is, yes, it could always have been even worse.”

Sane people in government would never have slashed their budgets. I sadly doubt enough of them are paying attention to this very loud wake-up call.

Given that AK got snubbed for FEMA aid after their tornadoes, I doubt Central TX will fare better. I never thought I’d see such deliberate neglect.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-O2nO60wXuU

This interview gives useful insights in my opinion.

I think the analogy of the budget cut football team with only 8 players is very appropriate. That team cannot play and win.

With all the resources available to us here in the 21st century, surely we can develop a viable warning system that can be used in any area prone to flash flooding.

A good system should be redundant. One challenge in the hill country is spotty cell service, nonexistent in areas for those with Verizon, but this seems addressable. Of course there are sirens loud enough to be heard in tents, RVs, and cabins. In rural areas volunteer fire departments use sirens to summon emergency personnel from miles away. What is needed is leadership and the will to implement and fund.