Coming into this hurricane season, there were breathless forecasts calling for anywhere from 20 to even 30 named storms from some folks. Government forecasts were more conservative but even they were the most active we’ve ever seen from NOAA. Colorado State, too. So, as we sit here on August 21st with next to nothing showing up in modeling for the next 7 to 10 days, it’s reasonable for the general public to ask questions about those forecasts.

Back on day one of hurricane season this year, we published a piece about ways this hurricane season could essentially fail, or at least turn out “less bad.” We advertise ourselves as no hype, which as comments occasionally show has good elements and bad elements (we seriously thank you all for your support and readership — and constructive feedback only helps us to do better!). But the question was basically “Are we overhyping this season?” And the answer was no: All the elements that you would want in place for a historically active season were in place. All those big time forecasts were justified.

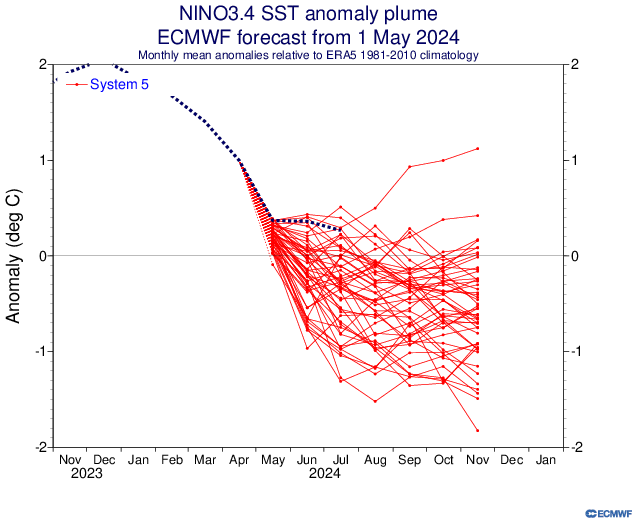

One of our potential fail modes was if La Niña developed too slowly. Indeed, the pace of the La Niña development this season, while uneven, has generally lagged the strongest projections. At least officially. Here’s a look at the May 1st European model ensemble outlook for the ENSO 3.4 region, the box of temperatures we look at to basically designate La Niña or El Niño.

We should begin closing in on an official La Niña designation in the next month or two, but we aren’t quite there yet. Keep in mind, this is by no means a perfect representation of things, and sometimes the atmosphere can behave more Niña-like even if we aren’t officially there yet. But this has not developed as aggressively as some modeling showed in developing in spring.

So, at a very, very distant level, perhaps that has something to do with it. Michael Lowry, in his excellent daily newsletter pointed out yesterday that wind shear has become almost too extremely reversed this month. Typically, during a La Niña, there is more of an easterly component from the wind that counteracts or reduces the usual west to east winds that can cause shear in the Atlantic, detrimental to hurricane development. In a twist of fate, there’s so much of an easterly component to the upper level winds this year that it’s actually causing easterly shear. Otherwise, we might be a good bit busier at the moment. If you look at the basin as a whole since June 1st, winds have been generally lighter than usual in the Caribbean and much of the Atlantic and a bit stronger than usual in the southwest Atlantic and in the Gulf.

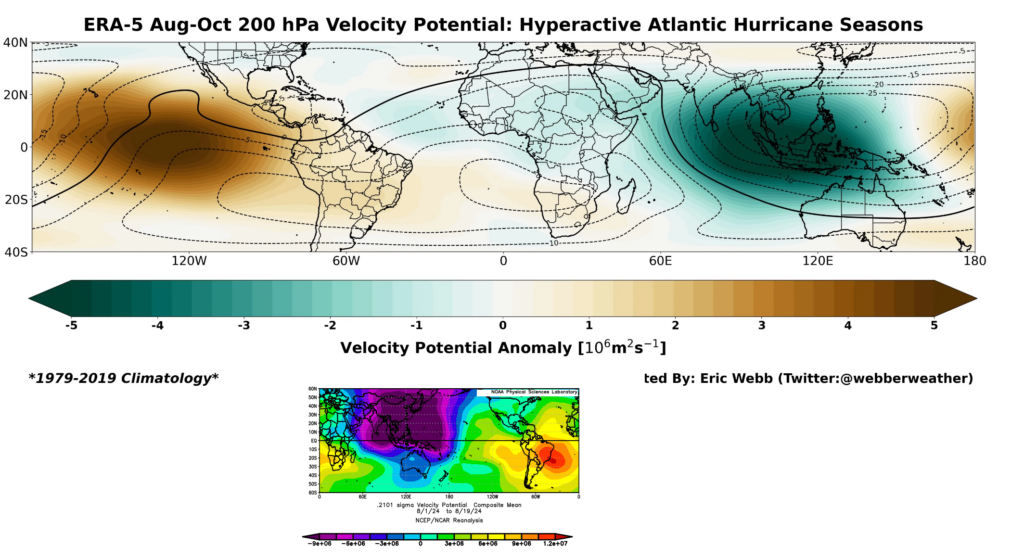

Let’s dig a little deeper. One thing that’s legitimately fascinating to me right now is what’s happening in terms of upper level background support in the atmosphere. Using a variable known as velocity potential, we can see that in historically active hurricane seasons, you would expect to see a significant area of rising air in the Indian Ocean, bleeding a bit into Africa (green on the top map below). Opposite to that, there would be a significant area of sinking air in the Eastern Pacific Ocean (brown colors below). Why is this important? In order to generate an active outbreak of storms in the Atlantic, you need disturbances tracking across Africa, which tend to get supported by rising air over and just east of there. You also prefer to see the Pacific undergoing sinking air, as a way to keep it from ‘robbing’ the favorable conditions for storminess. Sinking air suppresses thunderstorm development and tends to dry out the air a bit.

So what’s going on right now? So far this August, we’ve actually *had* what we would expect from a hyperactive season in the Indian Ocean. Click to enlarge the image below.

We have a ton of rising air in the Indian Ocean this month (purple & blue on the bottom map above). We have that extending into Africa. This is what you’d expect for a busy season. Where it differs, however is exactly where the sinking air (red/orange in the bottom panel above) is located. In a typical hyperactive season, this is focused over the Eastern Pacific. This year, it’s focused on the eastern side of South America. This is Matt speculating wildly here, but: I suspect that we’re seeing the right ingredients in place, but I think we are seeing them out of phase. The rising air in the Indian Ocean extends deeper into the Pacific, and there is more of a neutral Eastern Pacific signal right now. This is helping boost activity in the Pacific.

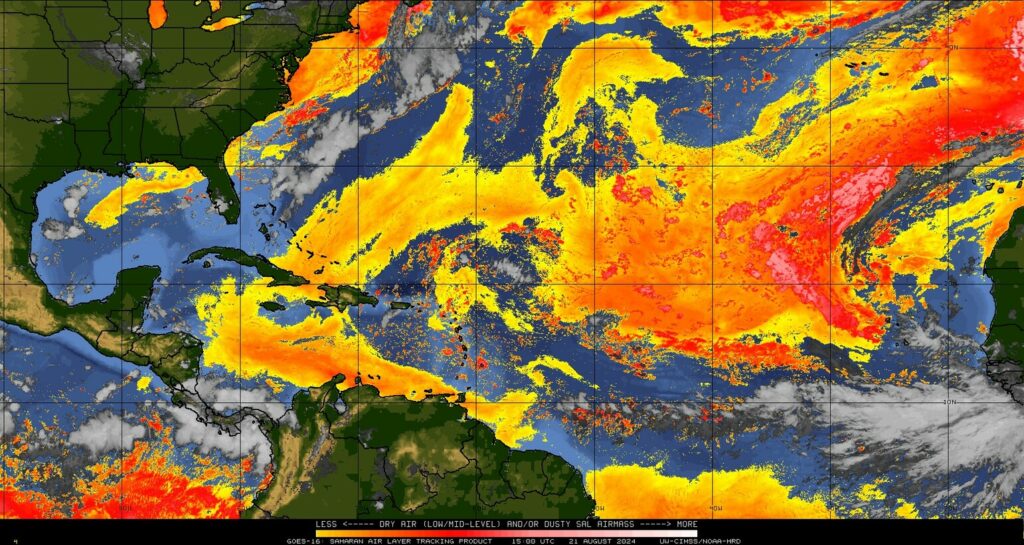

The problem with the tropics is that support like this generally moves from west to east, and eventually this will change. So the quiet now may change in a very, very quick way come September when this (presumably) shifts. For now, the Atlantic is still seeing rampant dust and a slightly displaced intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) which is sending disturbances off Africa too far north and into dust. So they die off earlier. This too will change.

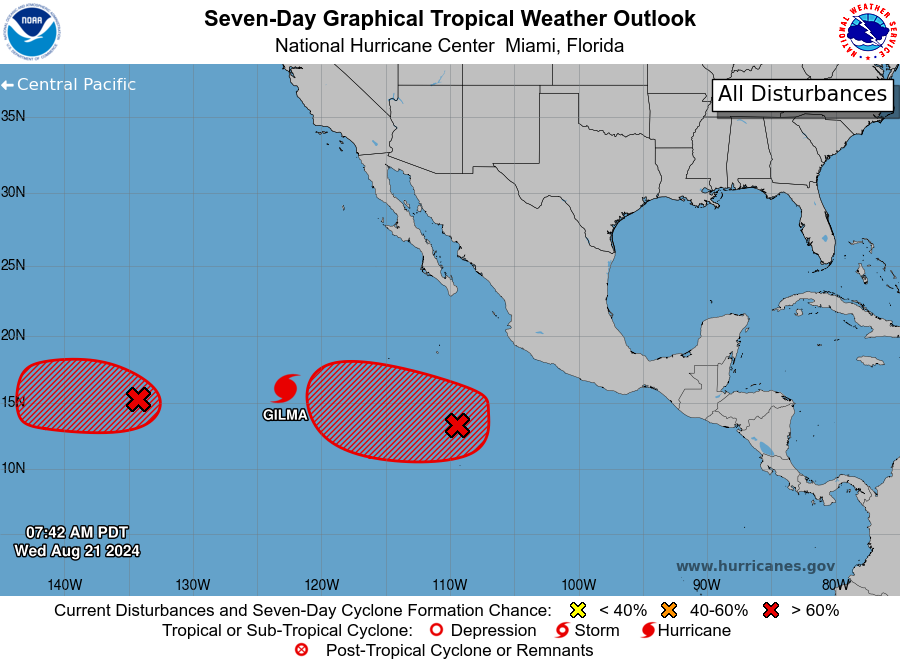

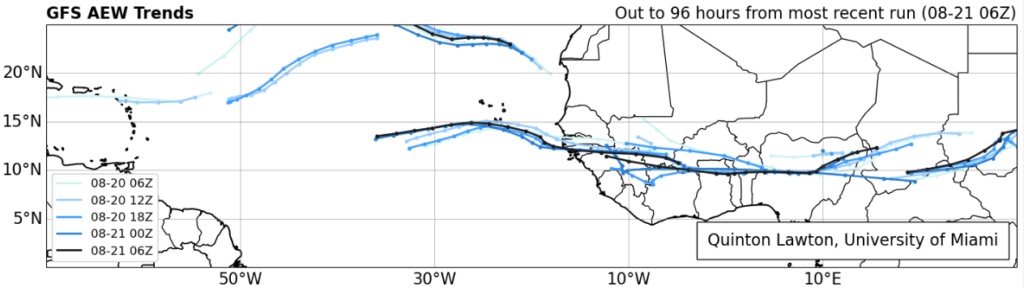

In fact, if you look at the forecast of African Easterly Waves (AEWs) from the latest GFS model, you can see this southward shift approaching heading into the next week or two. The waves lined up over Africa are about 5 to 10 degrees farther south in latitude about 4 days from now, which means they will emerge farther south and in more of a traditional area less exposed to Saharan dust in late August and September.

So, yes, things are almost certainly going to pick up soon.

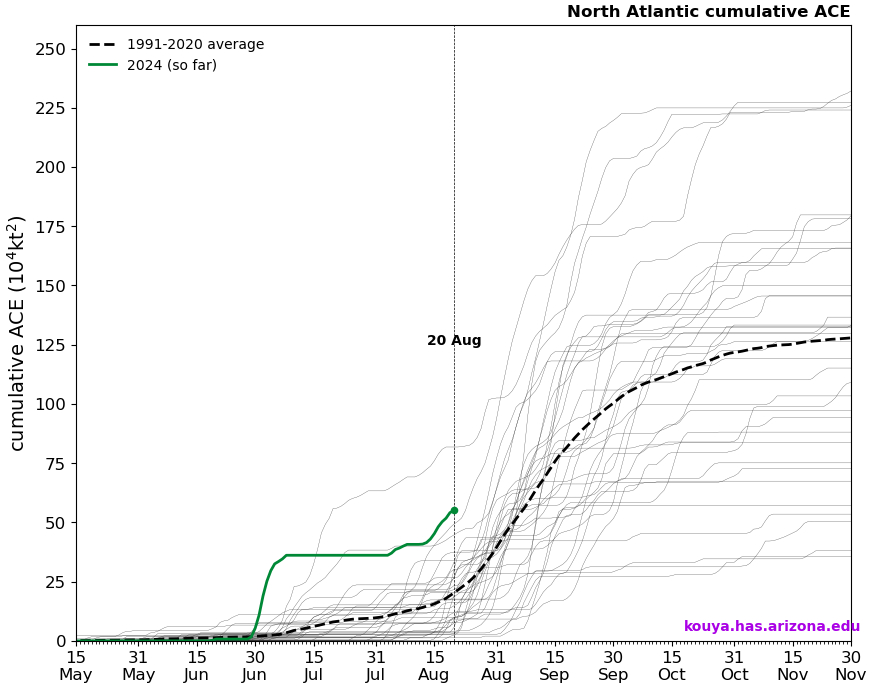

Despite perception, this season’s current accumulated cyclone energy is running nearly 3 times higher than usual! We’ve amassed as much ACE so far this season as we’d typically see by the peak day of hurricane season (September 10th). We’ve done this on the backs of only five storms so far, three of which have been hurricanes, and one of which (Beryl) smashed early season records in the Caribbean and Atlantic.

So despite the perception that this season has been slow to start, it actually has not been. In fact, 2024 is in rarefied air in terms of ACE to date. This perception might have to do with storm inflation, or the idea that we are naming more storms today than we did, say, 20 or 30 years ago. In 2020, basically the benchmark for recent historically active seasons, today marked the formation date for Hurricane Laura, the 12th named storm of the season. Here we are in 2024 sitting at five, and it’s no wonder the perception is skewed. Despite having more than twice as many storms to this point in 2020, we only had half the ACE (26 vs. 55 this year). 2020 kept churning out mostly sloppy storms until Laura, and then things got nasty. We’ve had three legitimate hurricanes this year and only about one “throwaway” storm (Chris). The takeaway message here is that: We can make up ground in September very, very fast. Very fast.

So, no, this season’s extremely active hurricane seasons have not been a bust so far, and they probably won’t end up being a bust overall. We’ve had a “bang for our buck” season so far with quality storms over quantity as, say, in 2020. And while we are in a lull now, the setup is probably going to change in 7 to 10 days to allow things to crank up in September. Never call it a bust. If it is one, we can discuss why in November. For now, use this quiet time to review your hurricane preparedness plans and supply kits. And stay tuned here for the latest through September.

Thanks, Matt. Very informative. For those of us who keep one eye on the tropics and one eye on the calendar, it has been calmer — so far — this season. By August of ‘17, we were at the “H” storm when Harvey blew in. And, in early September of ‘05, we are at the “K” storm with Katrina but had quickly jumped to Rita in just a few weeks. I’m fine with the lag, but it’s been my uneducated guess that September can be crazier for hurricanes (certainly in the GoM pointed at Texas) than August ever is. And, no, we are by no means out of the woods.

Thank you for the concise information. Very interesting to look at how the wind in the Indian Ocean affects us here in the Gulf states. Thanks.

What is with the higher than average wind shear forecasted in the Gulf the next few weeks? Isn’t La Nina supposed to inhibit wind shear?

The increased wind shear is great for Texas, but I expected less than average wind shear.

We’ve had some early season fronts make their way pretty far south (see heat index values running well under yesterday to our east). I’m guessing that has something to do with it. May not last beyond the next couple weeks though.

At least the next couple weeks is the timeframe for the greatest chance for a hurricane strike to Houston in the season. I’ll take it.

The CFS Weekly is showing 30-40 kt average over the northern Gulf for all its six week run, outside this week, so hopefully that is the case.

Is the natural gas infrastructure in Houston capable of sustaining operations through a Cat 5 storm? I guess restated, curious whether hurricanes such as Laura can demolish so many buildings, creating so many leaks, that the system is unable to maintain the supply for standby generators.

I would not think this would happen. More likely, you’d have isolated pockets where damage would be extreme, while in most other areas it would look more like Ike or Beryl.

Awesome post! Lots of great stuff to learn 💓

Better a siesta than a fiesta.

Thank you for all of your hard work! We can only hope that we don’t get another on especially since so many have had such a hard time!

I like the focus to be more on ACE than the number of named storms in the season. 2020 was a great example of why. Appreciate your insights.

Could the low slated for the Gulf around this weekend turn into a destructive storm for Houston?

The retreat of high pressure from west texas is probably not helping in the next couple of weeks or in Sept as that will keep Hurricane / storm away from here. Any insights in the high pressure movement for Sept or say in the short/long range? Thanks

For some balance, it would be nice to point out that Northern Hemisphere ACE is 60% of a normal year. Active in the Atlantic, yes….far from active in the Pacific and Indian oceans.

The seasonal forecasts we have been focused on are for strictly the Atlantic. Globally, yes, activity has been suppressed this year.

When I was a kid growing up I remember they only named warm tropical systems and counted them for each year. It seems to me about 10 or 15 years ago they started naming subtropical systems besides tropical. Wouldn’t that increase the numbers of tropical storms and hurricanes now compared to the earlier years of history?

Subtropical storms are more easily identifiable now, and I don’t think they influence the number of storms annually. However, they do tend to be easier to classify so there are naturally more of them now. That said, because technology has improved we can name more storms than we used to, which is why I referenced the concept of “storm inflation” in the post too.