In brief: Today we discuss the have too much’s and have too little’s of rainfall from July. We also briefly look at July’s temperatures. Meanwhile, August will begin quiet in the Atlantic, noisy in the Pacific, and just hot for many.

Recapping July’s rainfall

Apologies for some of the later day posts this week. Work obligations just take priority! Let’s look back at July real quick.

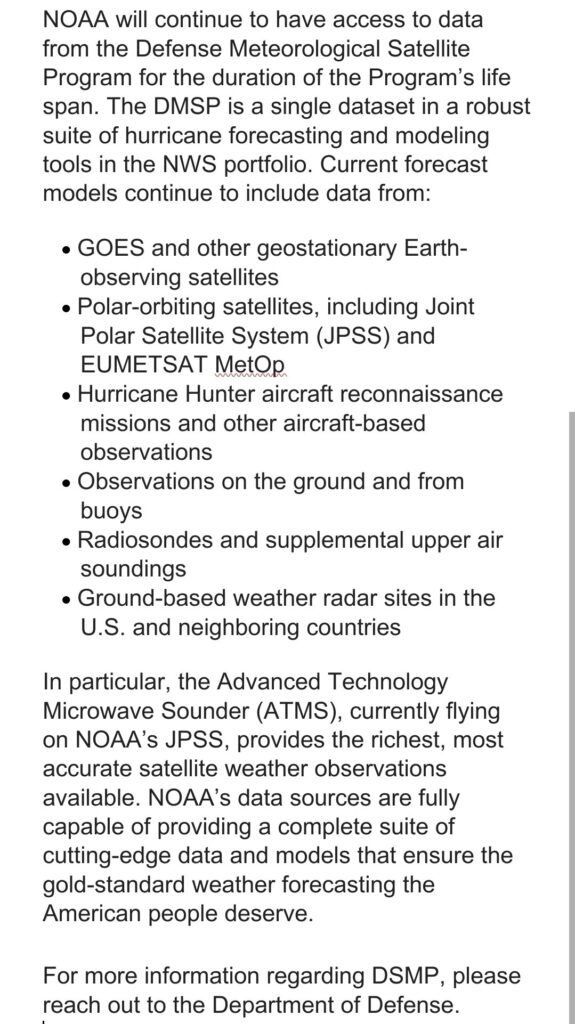

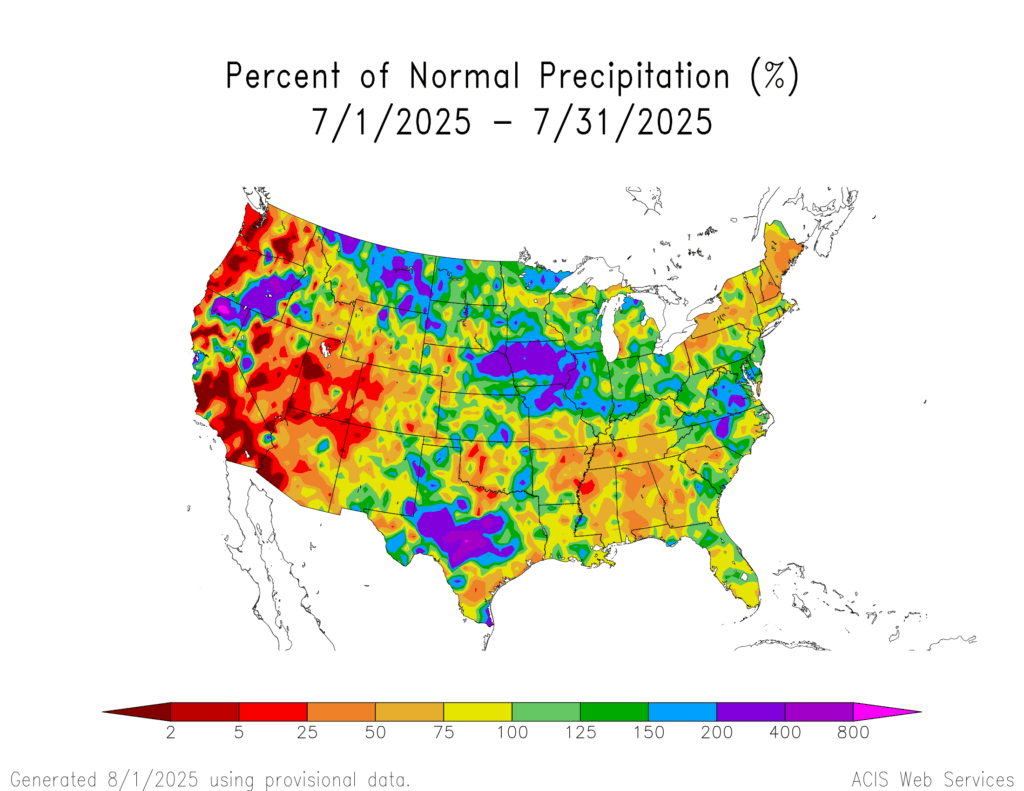

The areas that saw the most rainfall relative to normal last month included northern California and eastern Oregon, as well as the northern Rockies, Iowa, northern Missouri, Central Texas, and North Carolina and Virginia. Even with above normal rainfall in Oregon, some significant wildfires occurred there in July. Mount Shasta in California had its 5th wettest July on record.

Working east, it was the 7th wettest July on record in Glasgow, Montana and Norfolk, Nebraska. In Des Moines, Iowa July 2025 is the new wettest July on record. The capital of Iowa saw 10.62 inches of rain last month, just edging out July 1958.

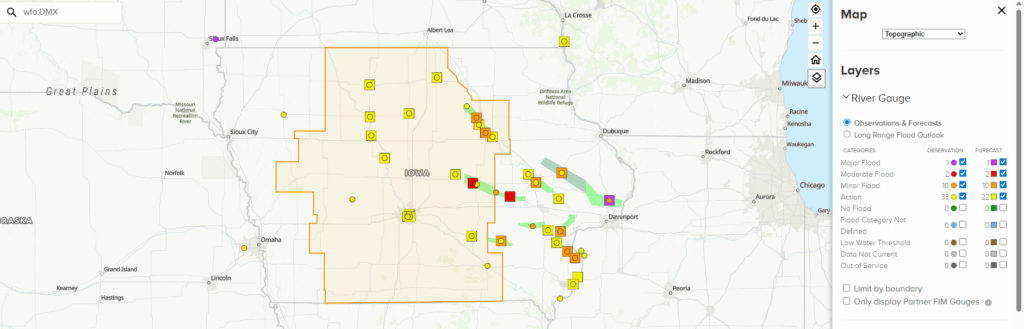

Numerous rivers are in flood or near flood across Iowa after such a wet month. Waterloo, Iowa had their 7th wettest July, while Moline, Illinois finished in 5th place. Kansas City ended up in 9th place.

In Texas, Austin finished 9th for July in precip. Obviously some parts of Hill Country likely finished higher than that, not just because of the July 4th tragedy but because it was a wet month overall. In Waco, it was the 7th wettest July. Moving east, Richmond, Virginia had their 8th wettest July, while Greensboro, North Carolina finished in 9th place.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, it was the 11th driest July on record in Manchester, NH, while it was the 4th driest July in Bangor, Maine. Meanwhile, in Seattle it was the 6th driest July on record with a mere 0.01″ of rainfall. Not that July is known to be a wet month in Seattle, but the average is still about 0.6 inches. In Eugene, OR July 2025 joined 12 other Julys with no rainfall back to 1893.

Phoenix saw less than a quarter-inch of rain last month, and Las Vegas only saw about 0.02 inches. The first megafire of 2025 in the Lower 48 is ongoing in Arizona. Typically, Phoenix and Vegas pick up about a half-inch to an inch of rainfall, less north, more south due to the monsoon. With a somewhat sluggish July in the precip department in Arizona, Utah, and Nevada, we are seeing wildfire issues instead. The Dragon Bravo fire has burned over 115,000 acres and is continuing to expand. This fire is responsible for the terrible damage earlier this month in the North Rim of the Grand Canyon.

Farther north, the Monroe Canyon fire is burning in Utah over 55,000 acres so far. This one appears to be growing significantly and has forced evacuations recently.

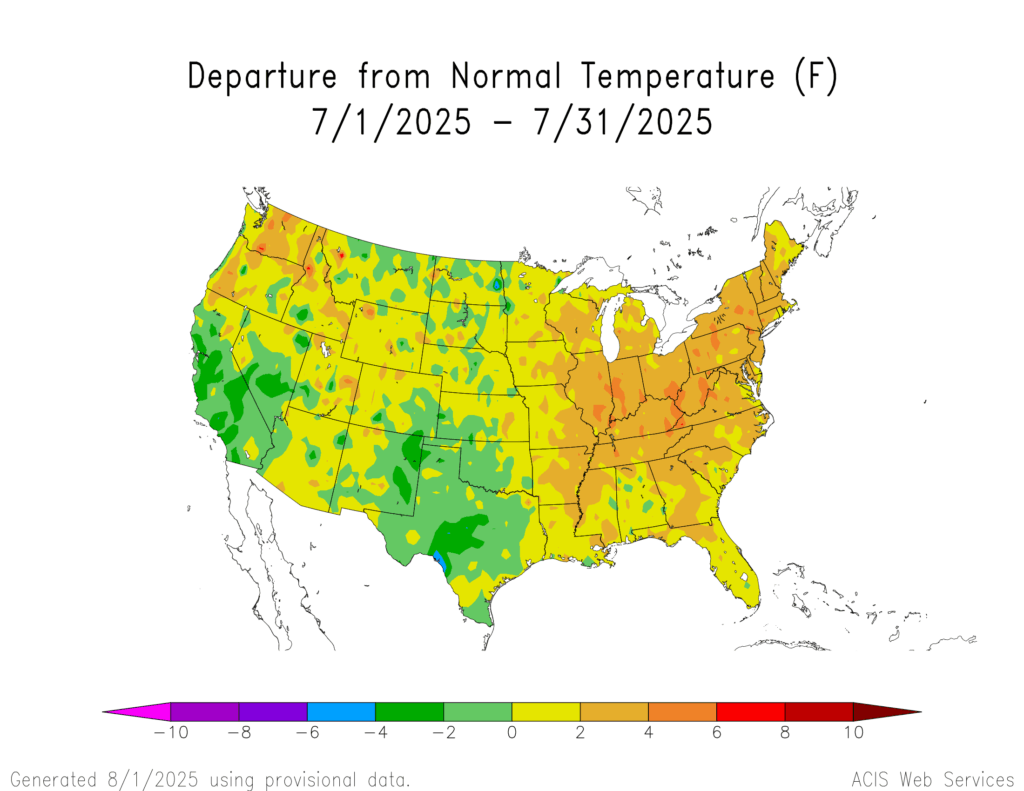

As far as heat goes, that’s a topic that we’ll perhaps dive into a little more on another day. But suffice to say, it was a hot month nationally.

For Indianapolis, it was the hottest July since 2012. It was 10th hottest on record in Pittsburgh. In Syracuse, it was the third top 10 hottest summer since 2020.

Dog days of summer are here

Anyway, onto August we go.

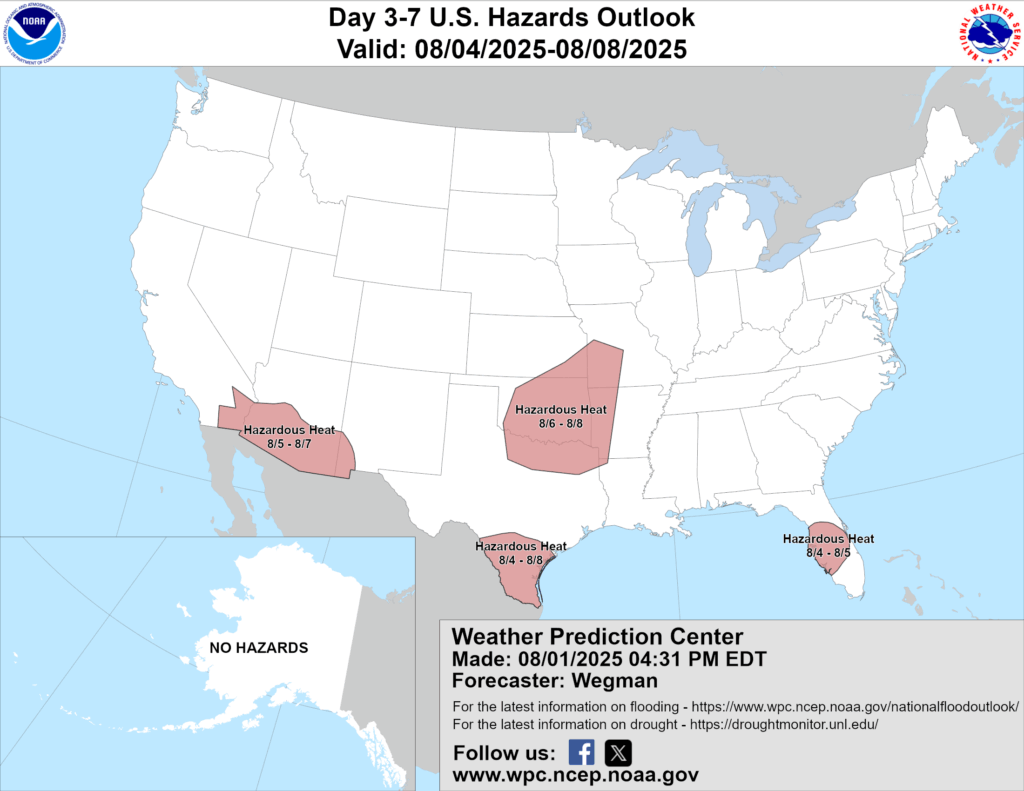

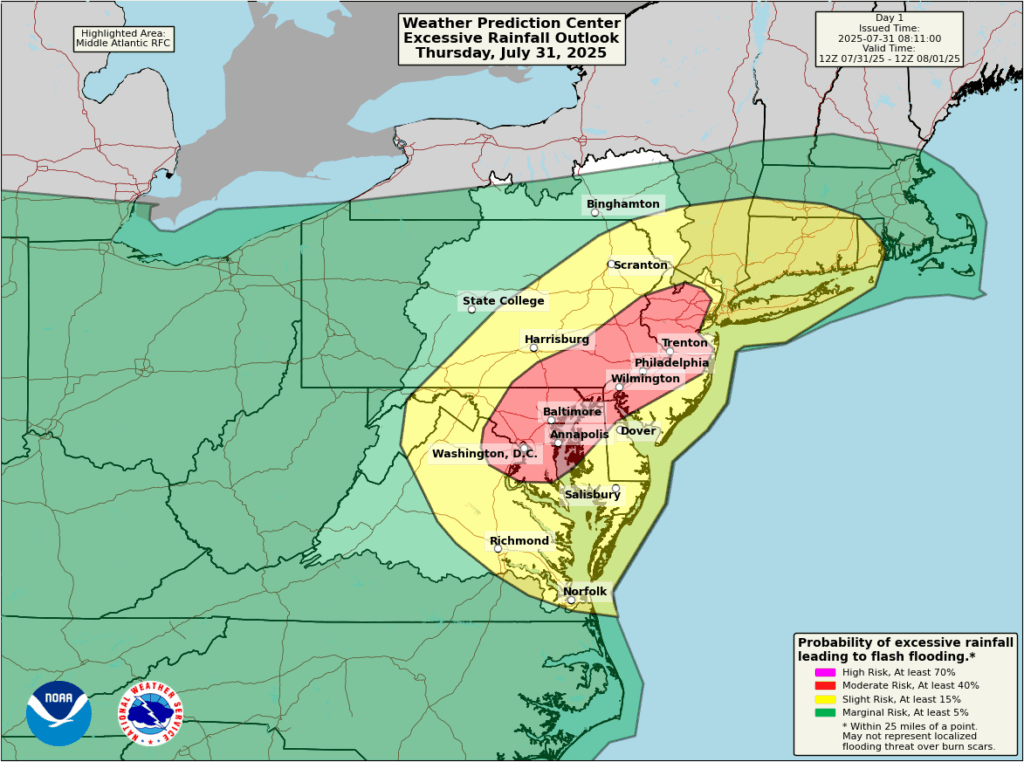

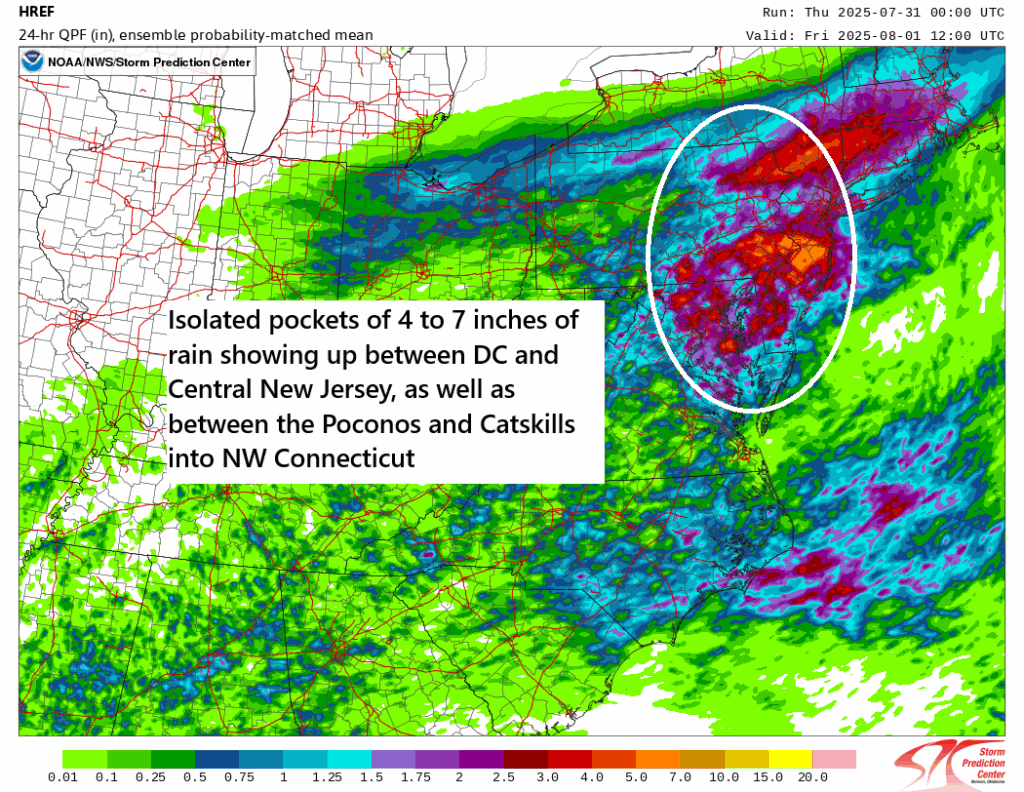

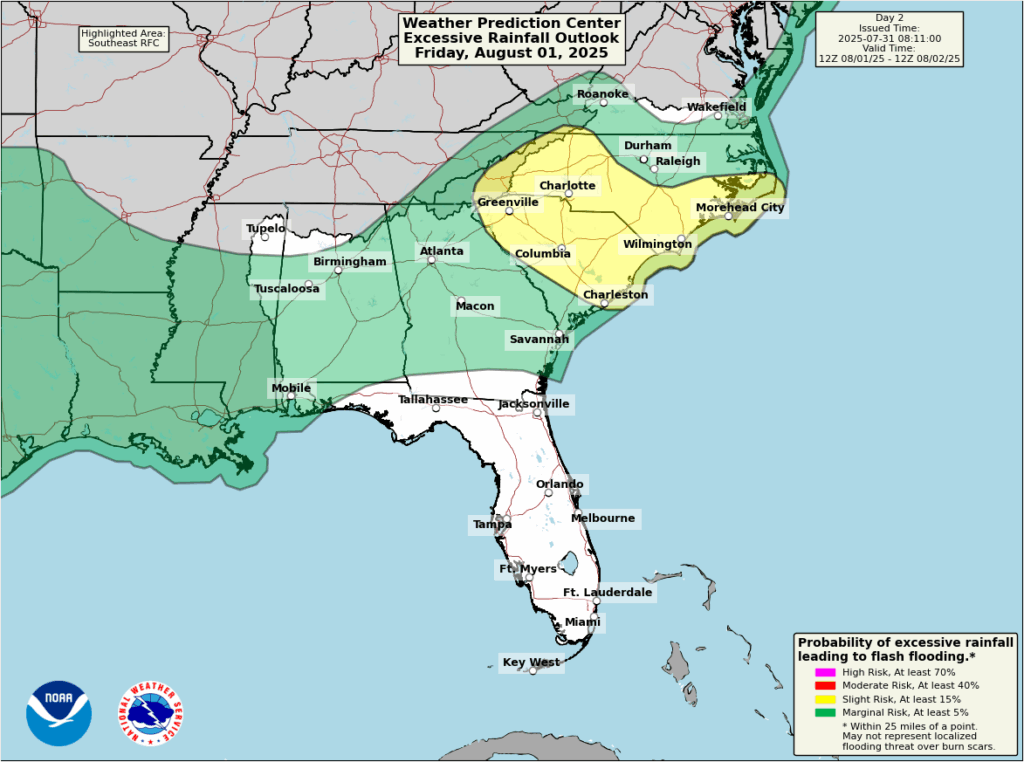

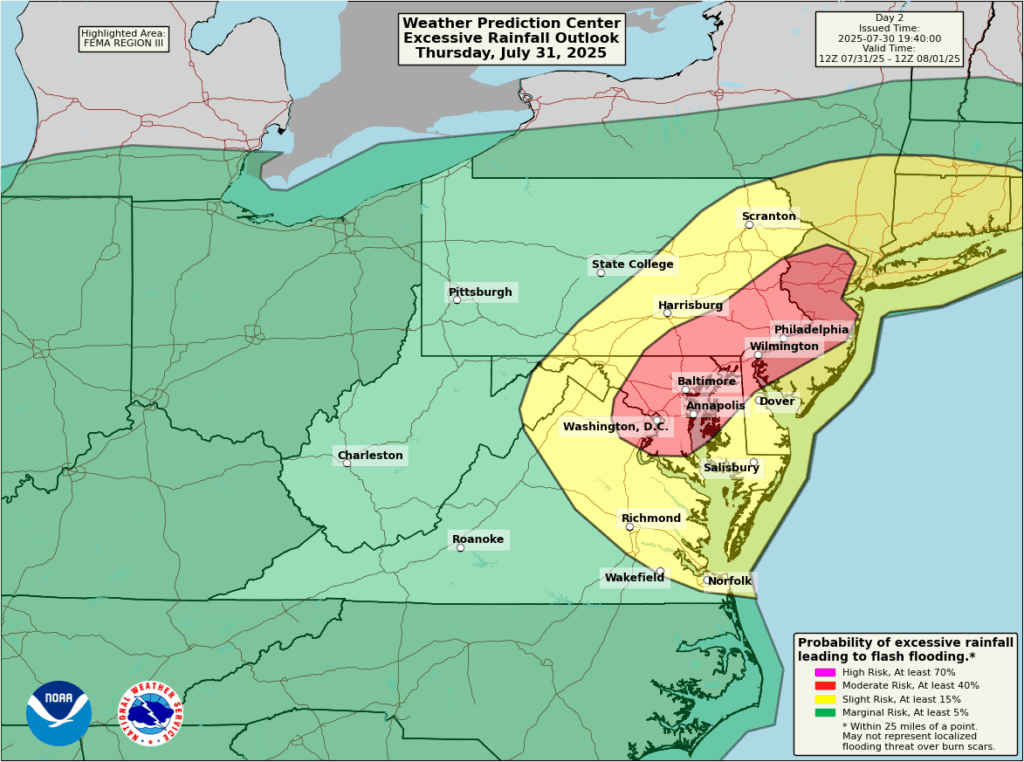

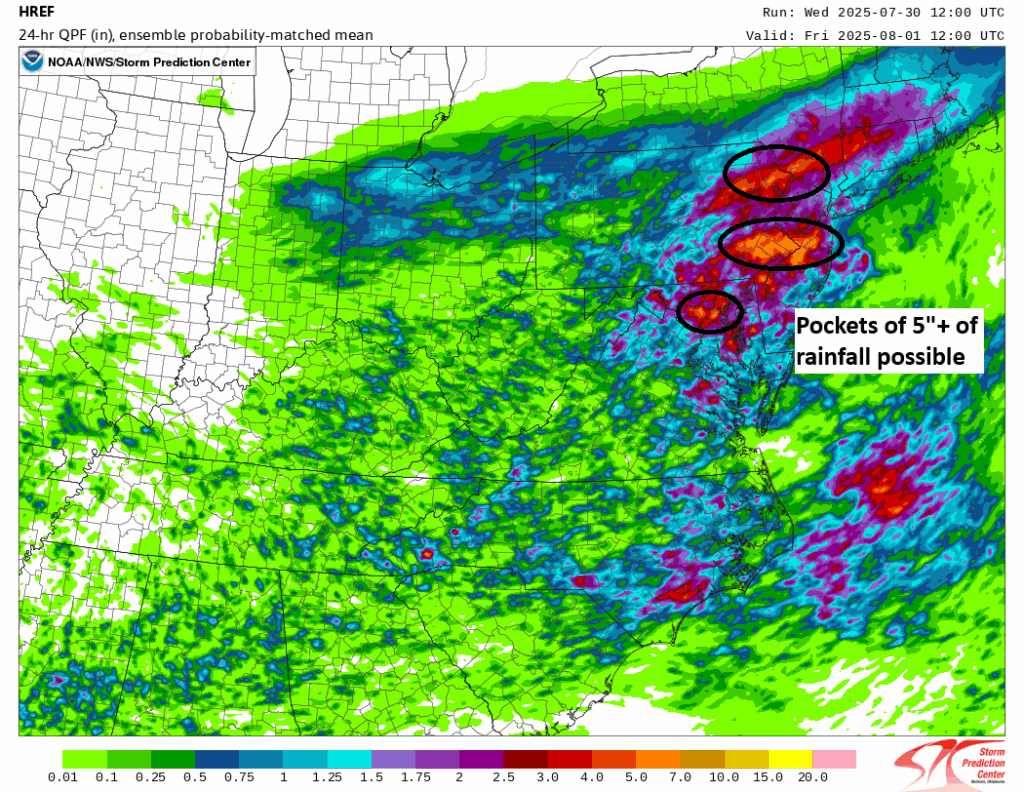

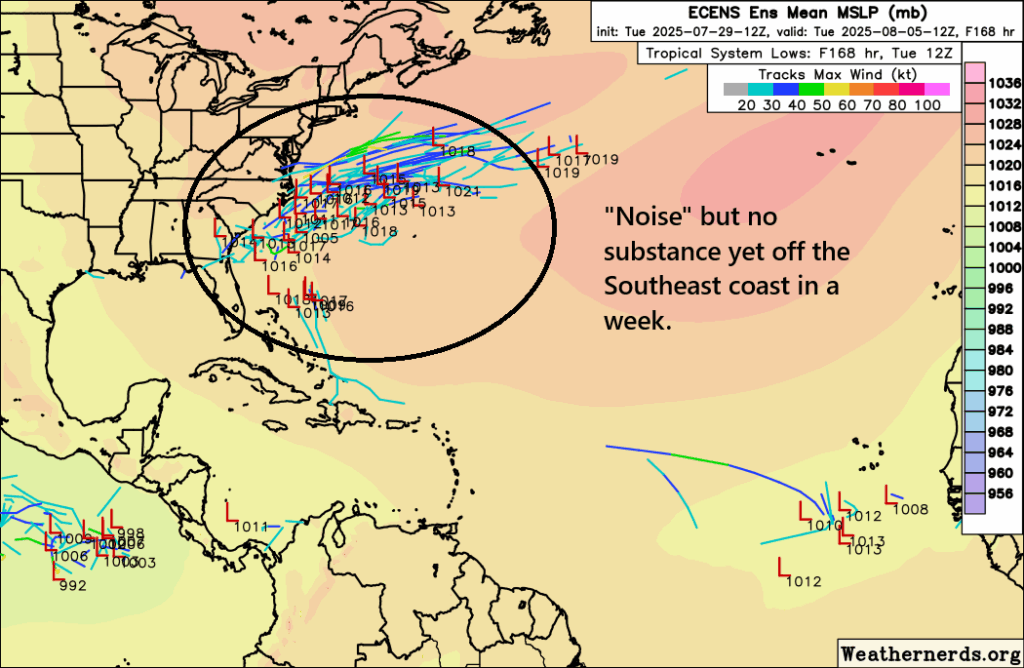

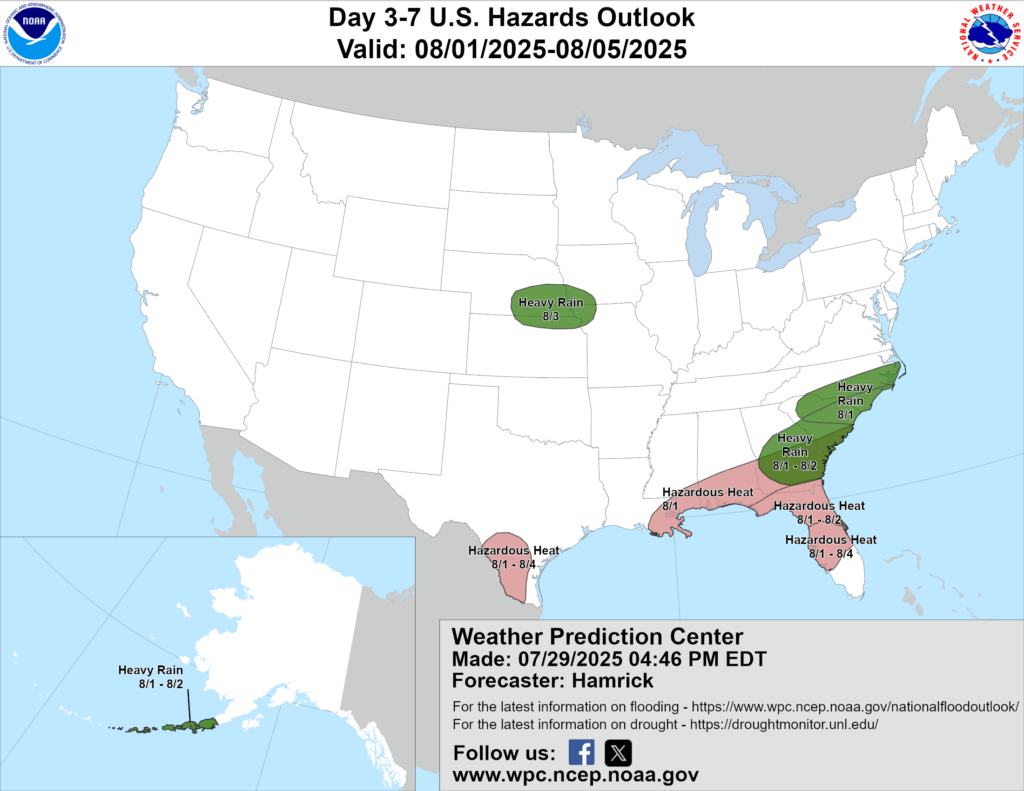

The main weather issue over the next 10 days or so will be heat. Yes, there will be pockets of strong storms and flooding around, but heat is going to begin to expand again next week from the Southwest into the Plains with a major ridge of high pressure setting up shop. We’ll probably see record temperatures at times from Arizona through Texas next week. August being August.

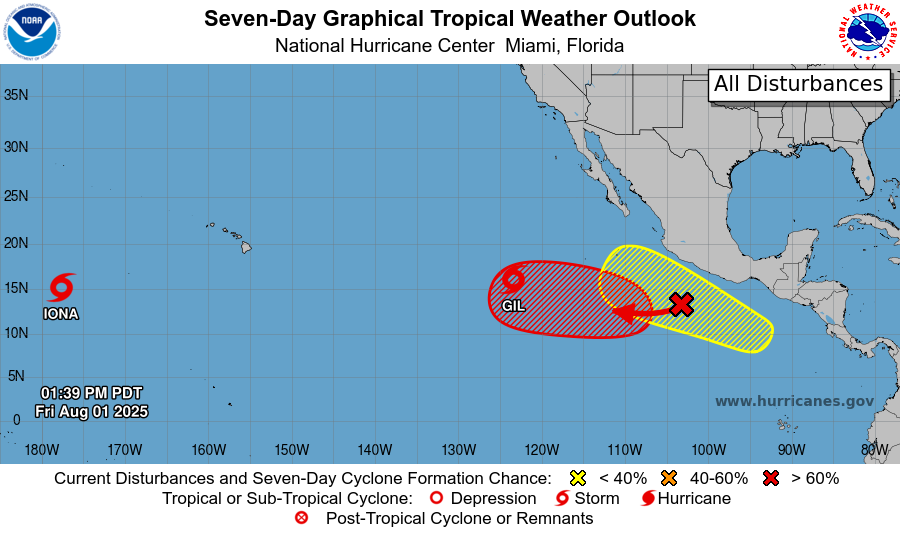

Tropical update

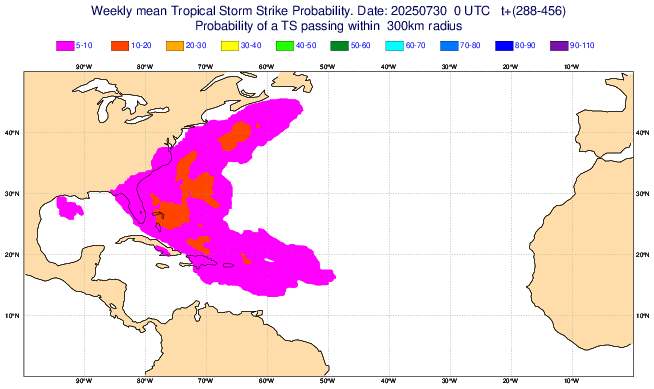

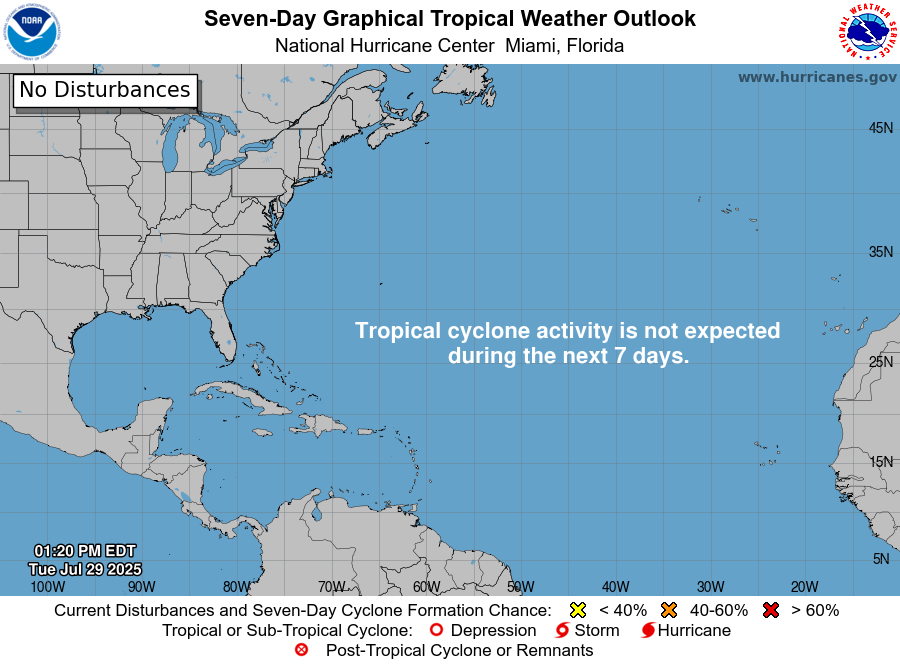

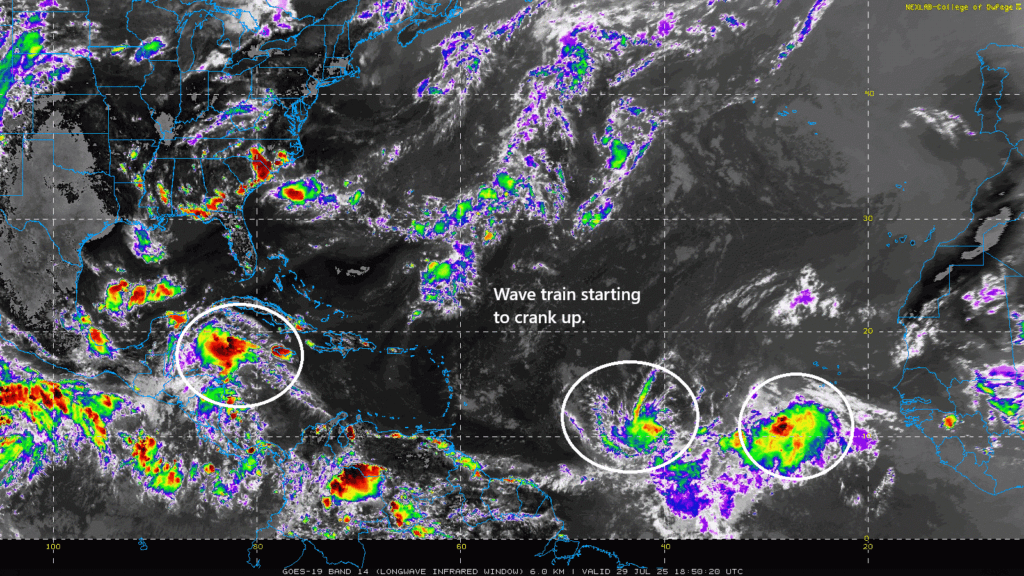

The tropics remain calm for now. I suspect we’ll have more to discuss next week. The Pacific is a beehive of activity, but none of these storms are likely to impact land at this time. Iona is heading deeper into the open Pacific and weakening. Gil should briefly become a hurricane before weakening as it passes well north of Hawaii.

The area behind Gil could become a little more interesting to watch as it relates to Hawaii, but that’s days away so it’s more likely to do nothing than impact Hawaii at this time. We’ll keep an eye on things.