I wrote a bit about the flooding this past week in Washington State over at The Eyewall. It was pretty bad. In some places, it was at record levels, others the worst since 1990, and so on. I neglected to look much at how the heavy precip and flooding was impacting Oregon. Or British Columbia.

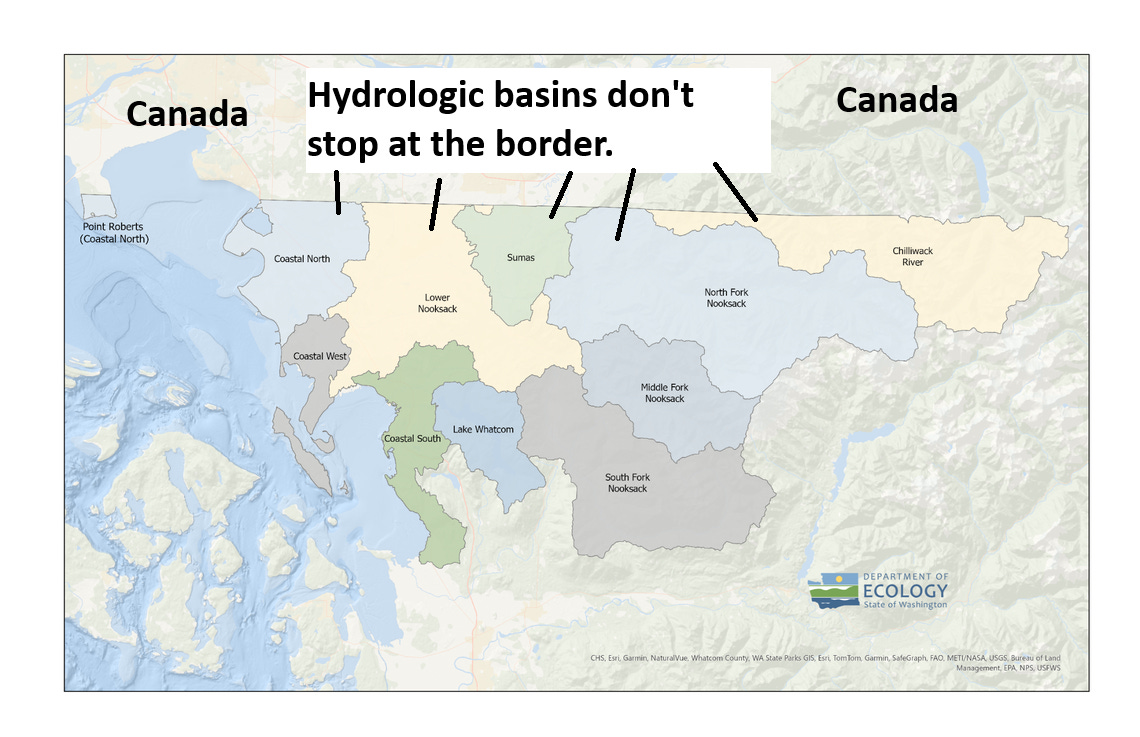

The Nooksack River sources in North Cascades National Park on Mt. Shuksan. It flows north and then west, eventually dumping into Bellingham Bay off Puget Sound. Because of the topography in that region, when the Nooksack River floods badly, it spills north into the Sumas River. The Sumas sources in Whatcom County, Washington and flows around past the Nooksack and dumps into the Fraser River in British Columbia northeast of Abbotsford.

As is often the case, the reason this is a problem is because of what we chose to do many years ago. This whole area is a leftover flat plain from glacial retreat that acts as a floodplain for the rivers. It is called the Sumas Prairie, but it actually used to be a lake. In the 1920s, the lake was diked and drained. This opened up a bunch of fertile land for farming, as well as reduced flooding on the Fraser River in Canada. But it also is a former lakebed, and water was there for a reason. Thus, in floods like this, the lake is attempting to refill, except now people live where a lake once sat. Essentially, the Nooksack watershed gets higher than the Sumas watershed, and water essentially “spills” downhill into the Sumas, which flows from Washington into Canada.

After the bad flooding in 1990, a cross-border group was created to propose flood mitigation measures, specifically near Everson, WA where the Nooksack overflows into the Sumas Prairie. Some modeling efforts were undertaken, some solutions proposed but as time wore on and urgency disappeared, nothing happened, and the effort sort of ended in 2011. After 2021 flooding, the effort was revived. The rub is that a solution that could help alleviate flooding in British Columbia and in Everson would probably cause disastrous effects downriver from there. So, you could fix one problem only to create new ones.

After this event, there will be renewed momentum to try and address this, but the problem is complicated. Some possible ways of solving the problem will take years and are quite costly. Other problems are similar in nature to problems we’ll have to address with respect to dams, which is sediment buildup. In the case of the Nooksack, the river has been constrained for years, when in reality it used to expand and contract. This has allowed for sediment to remain constrained and build up over years, reducing the capacity of the river to hold water, which is challenging even when we don’t factor in that atmospheric river events in the Northwest are becoming stronger. More water from the sky, less capacity to hold water on the ground, a natural floodplain, more flooding. It’s an extremely complex problem underpinned by pretty simple math.

This is not a problem isolated to Washington and British Columbia. On the other side of the countries, flooding problems led to the International Joint Commission (created from the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty to investigate and come up with joint solutions for U.S.-Canada water challenges) to propose solutions to flooding on the Lake Champlain-Richelieu River basin shared between Quebec, Vermont and New York. The IJC has not yet been involved with the issues in Washington and British Columbia.

Locally in my world, there’s an issue right now between Harris County and Montgomery County in Texas. A proposed development in Montgomery County west of a particularly flood prone community in the Houston area (Kingwood in Harris County) forced a Harris County precinct commissioner to push out a high-level resolution requesting that Montgomery County ensure the development adopts Harris County’s minimum drainage standards. Montgomery County has generally weaker standards for developments than does Harris County. In this instance, their choices could directly impact the outcomes for people that do not live in their jurisdiction.

In Canada, Abbotsford’s mayor is not happy with Canada’s federal government or with their neighbors in Washington. In addition to the issues around Lake Champlain and the Richelieu, the IJC did adjudicate and come up with a bunch of recommendations after the horrific 1997 Red River of the North flood that impacted the Upper Midwest and Manitoba. In 2017, they issued a report showing how a good chunk of the effort had succeeded. In Asia, there have been and will continue to be tensions over how countries, in particular China and India manage substantial quantities of water that source in their regions and flow into other nations. In Africa, dam building on the Nile in Ethiopia has created significant tension downstream in Egypt where they believe they have superior water rights on the river.

At what point does it become one community’s responsibility to ensure an adjacent one is not negatively impacted by decisions they make? Look at the Colorado River for one. This is less about flooding and more about water rights, but there are substantial tensions between the upper and lower basins (not to mention tribal nations) over this question. These are not easy problems to solve. But they do require coordination and cooperation. We have that to some degree with the Colorado River, which is governed by the 1922 Colorado River Compact. But when you have a patchwork of requirements and regulations rather than a single agency overseeing an entire region it can make for difficulties, such as in Southeast Texas, where decisions made in rapidly growing counties can impact many neighborhoods in the Houston area. The counties bordering Harris County have grown by nearly 1 million people in the last 15 years. Harris County itself has grown by nearly a million people in that same time. The growth is likely to continue. A formalized regional regulatory approach to flooding in this area is not currently in progress.

But these are the things we’re going to need to be thinking about as flooding likely continues to worsen. Climate change will get the oxygen for a lot of these issues. And it’s obviously a major factor. But it’s not just climate change. In the case of the Sumas/Nooksack flooding, it’s pretty much because we chose to drain a lake in the 1920s that existed for this specific reason, and we decided to constrain the flow of the river leading to sediment buildup and less room for water. In the Houston area we are eradicating prairie and former farmland in differing jurisdictions with differing requirements for building and quickening runoff. In the Colorado River, we are sharing a scarce resource and have dammed the river up. Rather than treating the Washington-British Columbia problems as an unfortunate circumstance from an extreme weather event, it should be a (yet another) wake-up call about some of the decisions we make as people in charting our growth.