As we navigate the world right now, we have an obligation to keep our readers informed on the news of the day as it relates to weather forecasting. After all, if you are using this site and others for weather forecast information, you have an interest. But there’s a lot of news out there, and a lot of opinions masquerading as news. No matter your political leanings, the “zone” as it were is flooded and trying to piece together facts vs. stretched truths can be difficult in any ideology. So, periodically I think it helps to take a step back and assess a topic as realistically as possible. This is meant to be as unbiased a look as possible at one topic of note: Weather balloon launches being cut.

What is happening?

Due to staffing constraints, as a result of recent budget cuts and retirements, the National Weather Service has announced a series of suspensions involving weather balloon launches in recent weeks.

On February 27, it was announced that balloon launches would be suspended entirely at Kotzebue, Alaska due to staffing shortages. In early March, Albany, NY and Gray, Maine announced periodic disruptions in launches. Since March 7th, it appears that Gray has not missed any balloon launches through Saturday. Albany, however, has missed 14 of them, all during the morning launch cycle (12z).

The kicker came on Thursday afternoon when it was announced that all balloon launches would be suspended in Omaha, NE and Rapid City, SD due to staffing shortages. Additionally, the balloon launches in Aberdeen, SD, Grand Junction, CO, Green Bay, WI, Gaylord, MI, North Platte, NE, and Riverton, WY would be reduced to once a day from twice a day.

What are weather balloons anyway?

In a normal time, weather balloons would be launched across the country and world twice per day right at about 8 AM ET and 8 PM ET (one hour earlier in winter), or what we call 12z and 00z. That’s Zulu time, or Noon and Midnight in Greenwich, England. Rather than explain the whole reasoning behind why we use Zulu time in meteorology, here’s a primer on everything you need to know. Weather balloons are launched around the world at the same time. It’s a unique collaboration and example of global cooperation in the sciences, something that has endured for many years.

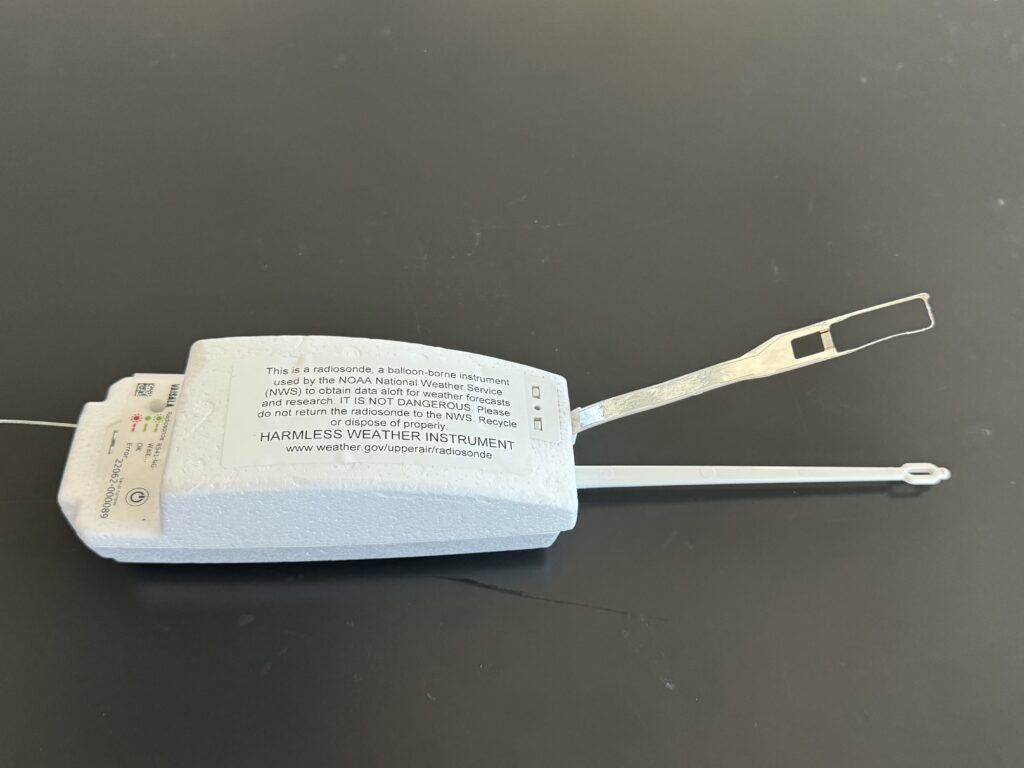

These weather balloons are loaded up with hydrogen or helium, soar into the sky, up to and beyond jet stream level, getting to a height of over 100,000 feet before they pop. Attached to the weather balloon is a tool known as a radiosonde, or sonde for short. This is basically a weather sensing device that measures all sorts of weather variables, like temperature, dewpoint, pressure, and more. Wind speed is usually derived from this based on GPS transmitting from the sonde. What goes up must come down, so when the balloon pops, that radiosonde falls from the sky. A parachute is attached to it, slowing its descent and ensuring no one gets plunked on the head by one. If you find a radiosonde, it should be clearly marked, and you can keep it, let the NWS know you found it, or dispose of it properly. In some instances, there may still be a way to mail it back to the NWS (postage and envelope included and prepaid).

What does the data from weather balloons do?

In order to run a weather model, you need an accurate snapshot of what we call the initial conditions. What is the weather at time = zero? That’s your initialization point. Not coincidentally, weather models are almost always run at 12z and 00z, to time in line with retrieving the data from these weather balloons. It’s a critically important input to almost all weather modeling we use. The data from balloon launches can be plotted on a chart called a sounding, which gives meteorologists a vertical profile of the atmosphere at a point. During severe weather season, we use these observations to understand the environment we are in, assess risks to model output, and make changes to our own forecasts. During winter, these observations are critical to knowing if a storm will produce snow, sleet, or freezing rain. Observations from soundings are important inputs for assessing turbulence that may impact air travel, marine weather, fire weather, and air pollution. Other than some tools on some aircraft that we utilize, the data from balloon launches is the only real good verification tool we have for understanding how the upper atmosphere is behaving.

Haven’t we lost weather balloon data before?

We typically lose out on a data point or two each day for various reasons when the balloons are launched. We’ve also been operating without a weather balloon launch in Chatham, MA for a few years because coastal erosion made the site too challenging and unsafe. Tallahassee, FL has been pausing balloon launches for almost a year now due to a helium shortage and inability to safely switch to hydrogen gas for launching the balloons. In Denver, balloon launches have been paused since 2022 due to the helium shortage as well.

Those are three sites though, spread out across the country. We are doubling or tripling the number of sites without launches now, many in critical areas upstream of significant weather.

Can’t satellites replace weather balloons?

Yes and no. On one hand, satellites today are capable of incredible observations that can rival weather balloons at times. And they also cover the globe constantly, which is important. That being said, satellites cannot completely replace balloon launches. Why? Because the radiosonde data those balloon launches give us basically acts as a verification metric for models in a way that satellites cannot. It also helps calibrate derived satellite data to ensure that what the satellite is seeing is recorded correctly.

But in general, satellites cannot yet replace weather balloons. They merely act to improve upon what weather balloons do. A study done in the middle part of the last decade found that wind observations improved rainfall forecasts by 30 percent. The one tool at that time that made the biggest difference in improving the forecast were radiosondes. Has this changed since then? Yes, almost certainly. Our satellites have better resolution, are capable of getting more data, and send data back more frequently. So certainly it’s improved some. But enough? That’s unclear.

An analysis done more recently on the value of dropsondes (the opposite of balloon launches; this time the sensor is dropped from an aircraft instead of launched from the ground) in forecasting west coast atmospheric rivers showed a marked improvement in forecasts when those targeted drops occur. Another study in 2017 showed that aircraft observations actually did a good job filling gaps in the upper air data network. Even with aircraft observations, there were mixed studies done in the wake of the COVID-19 reduction in air travel that suggested no impact could be detected above usual forecast error noise or that there was some regional degradation in model performance.

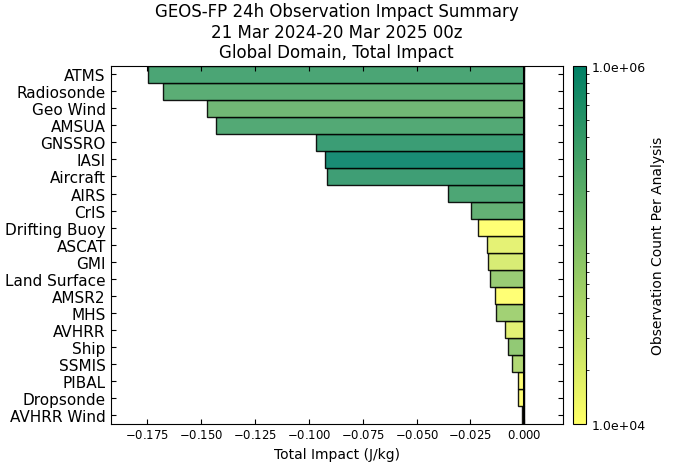

(NASA)

But to be quite honest, there have not been a whole lot of studies that I can find in recent years that assess how the new breed of satellites has (or has not) changed the value of upper air observations. The NASA GEOS model keeps a record of what data sources are of most impact to model verification with respect to 24 hour forecasts. Number two on the list? Radiosondes. This could be considered probably a loose comp to the GFS model, one of the major weather models used by meteorologists globally.

What’s the verdict?

In reality, the verdict in all this is to be determined, particularly statistically. Will it make a meaningful statistical difference in model accuracy? Over time, yes probably, but not in ways that most people will notice day to day.

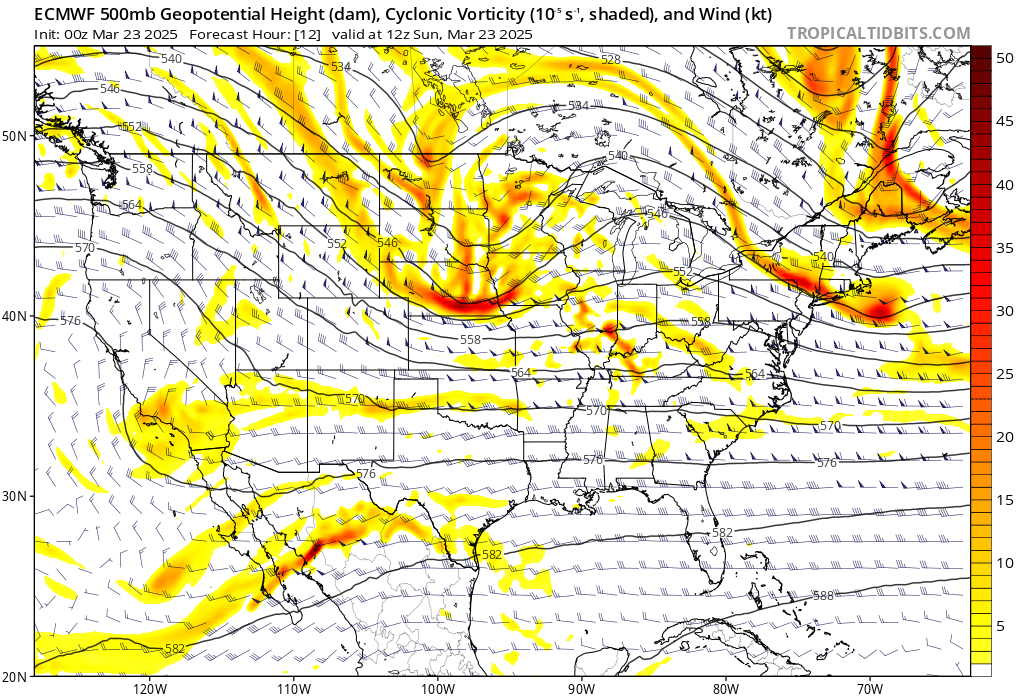

However, based on 20 years of experience and a number of conversations about this with others in the field, there are some very real, very serious concerns beyond statistics. One thing is that the suspended weather balloon launches are occurring in relatively important areas for weather impacts downstream. A missed weather balloon launch in Omaha or Albany won’t impact the forecast in California. But what if a hurricane is coming? What if a severe weather event is coming? You’ll definitely see impacts to forecast quality during major, impactful events. At the very least, these launch suspensions will increase the noise to signal ratio with respect to forecasts.

In other words, there may be situations where you have a severe weather event expected to kickstart in one place but the lack of knowing the precise location of an upper air disturbance in the Rockies thanks to a suspended launch from Grand Junction, CO will lead to those storms forming 50 miles farther east than expected. In other words, losing this data increases the risk profile for more people in terms of knowing about weather, particularly high impact weather.

Let’s say we have a hurricane in the Gulf that is rapidly intensifying, and we are expecting it to turn north and northeast thanks to a strong upper air disturbance coming out of the Rockies, leading to landfall on the Alabama coast. What if the lack of upper air observations has led to that disturbance being misplaced by 75 miles. Now, instead of Alabama, the storm is heading toward New Orleans. Is this an extreme example? Honestly, I don’t think it is as extreme as you think. We often have timing and amplitude forecast issues with upper air disturbances during hurricane season, and the reality is that we may have to make some more frequent last second adjustments now that we didn’t have to in recent years. As a Gulf Coast resident, this is very concerning.

I don’t want to overstate things: Weather forecasts aren’t going to dramatically degrade day to day because we’ve reduced some balloon launches across the country. They will degrade, but the general public probably won’t notice much difference 90 percent of the time. But that 10 percent of the time? It’s not that the differences will be gigantic. But the impact of those differences? That could very well be gigantic, put more people in harm’s way, and increase the risk profile for an awful lot of people. That’s what this does: It increases the risk profile, it will lead to reduced weather forecast skill scores, and it may lead to an event that surprises a portion of the population that isn’t used to be surprised in the 2020s. To me, that makes the value of weather balloons very, very significant, and I find these cuts to be extremely troubling.

One addendum that I have edited to add: This is our current situation. It’s a static look at a fluid problem. Should further cuts in staffing lead to further suspensions in weather balloon launches, we will see this problem magnify more often and involve bigger misses. In other words, the impacts here may not be linear, and repeated increased loss of real-world observational data will lead to very significant degradation in weather model performance that may be noticed more often than described above.

I’m just glad that the ultra rich can get even more money thanks to these cost savings along with all the other cuts to essential services.

You make very commonsensical points, and if you are correct, the balloon launches will be restored to prior frequency.

I find it interesting that you are so sure that government, no matter who is in power, would behave in a commonsensical way.

This has proven to be false now and in the past so I am not sure why you would think it would be in the future.

I hope you are right but I am not holding my breath.

There is no good faith reading of this post that can lead you to the evaluation expressed in your comment.

thanks for the knowledge about weather balloon shortage.

‘reduction in force’ programs might be exempted

or alleviated if proper rationale is documented.

i.e. tell of consequences to grounded politicians.

I wonder how the private weather companies such as the Weather Channel view this shortsighted slashing of government services. This will eventually affect their bottom line, unless they decide to use sharpies instead.

This is another case of the consequences of the chainsaw approach to reducing government staffing. Musk et. Al. won’t suffer any meaningful consequences, but the probability of those of us who are not super-rich facing them will. Government is fundamentally different than the private sector. Most people benefit from it’s services even though they don’t know it.

As a scientist, and someone who strongly believes in and supports the sciences, I found the description of this massively coordinated data collection effort fascinating, but lacking. You didn’t say exactly how many launch sites there are … but, there are many. And what is each balloon made of? Presumably, it’s an unsustainable material that floats down to join all the rest of the earthly trash. And the single-use weather device transmits data for a few minutes before it also joins all the rest of the earthly trash. And this happens at all these launch sites twice a day, every day?? And then there’s the helium that must be produced, stored and transported to all these sites … how much carbon does that produce? That describes a monumentally wasteful process that, at least in part, monitors climate change while adding to it. You must agree that there has to be a better way.

Wow.

Nice deflection.

Yes, there has to be a better way, but you don’t randomly cut off necessary data streams until there’s a way to replace such inputs.

You just fabricated a whole bunch of suppositions out of thin air, treated them as givens, and then concluded that something you confess to having no knowledge of is bad, based of the things you made up.

What’s your area of scientific study? Phrenology? Creationism?

You mention 11 sites where launches have been cut. How many launch sites are there nationally? What percentage of launch sites does this cut group make up?

Google says about 100.

There are approximately 92 in the US and territories, so 11 of them represents about 12%. But I wanted to also highlight *where* the cut sites are, which is almost as important as the number of sites it represents.

EVERYONE has specific priorities as regards to what taxpayer dollars should be spent on. There is so much wasteful spending, fraud, and abuse, on the backs of taxpayers. This goes on from both sides of the aisle. How about giving the current administration a chance to sort through and identify the bloat and waste. At some point, the appropriate spending priorities will likely be addressed. If the spending and the debt are not addressed…the last thing that US citizens will think about is weather balloon launches. I commend the current administration for finally addressing the spending. We are all entitled to our own opinions. My opinion is that weather balloon launches do not even show up on my radar screen as a spending priority. Too many other much more important issues to address first.

But they’re making no effort to identify bloat or waste. They’re cutting programs that the right disagrees with or finds inconvenient, without even attempting to follow any kind of responsible—or even legal—process. We’re witnessing the right’s revenge tour, not a good-faith attempt at eliminating waste.

If the people doing the cutting were actually attempting to reduce waste, they wouldn’t keep having their cuts overturned by the judiciary as illegal. They wouldn’t force agencies to cut blindly. There wouldn’t be unqualified 19-year old SpaceX interns gaining access to private taxpayer information.

If the administration cared about doing what you say, they’d do it properly, legally, and without cutting the things they’ve cut. The lack of focus on ACTUAL money wastes is hilarious, as Boeing walks off with another boondoggle cost-plus fighter contract.

Is carrying all that water heavy?

That is a very good statement you made, Also Id like to add if 90% of launches are predictable they may be able reduce the total number of launches but for turbulent storm systems i do think they’re very vital

My thought is that the Trump administration is downsizing these important functions so that the administration can say, “see, the weather service is no good and the private sector can do a better job, so let’s privatize it.” Look at Project 2025.

I am very sorry this is happening across all sectors of government with no thoughtful planning.

I agree with you 100 percent, Matt. This is very troubling – but also intentional. This administration is all about sowing chaos into everyday life, and this is yet another example.

I’ve been around a long time, seen a lot of hurricanes. Never felt this level of angst in regards to either wx in general or hurricanes in particular.

I have never trusted a meteorologist the way I trust both Matt & Eric –> they factor in the human element into this Rapidly Intensifying nightmare we find ourselves in.

I hope SWC knows how much they are needed and valued. Stars in their crowns.

🌟🌟🌟

*SCW

😉

All so very sad….I really have no words to express how devastating to us all that the cuts across all federal departments will be.

Thank you so much for this information and for all of the hard work you guys do.

I think the idea that costs need to be minimized and if there is waste and fraud it should be eliminated a commendable initiative. I also think the things like the balloon launches being cut are not anything to do with waste, or fraud, or actionable cost cutting. This isn’t the forum for a discussion about the current politics in this country but I must say removing the work NOAA does is of no benefit to the society at large and indeed maybe harmful in the long run. Our country can afford NOAA and NASA and several other science based agencies what we can’t afford is thoughtless reduction of services in an effort to continue tax breaks that disproportionally advantage the most wealthy. Thanks for your post Matt and for sharing your understandable concerns.

Thanks for the well thought out explanation…Rita anyone!

Thanks for a very sobering analysis.

I understand the consequences of having less weather data for predicting storms, etc. What I’m confused about is how better predictions of hurricanes saves “billions” of dollars, as was mentioned in the Feb 27 post. While better forecasts make us better prepared, if a strong storm hits, the greatest dollar cost is to buildings and infrastructure that are immovable. Simply predicting a storm’s strength and path can save lives and things that can be moved ahead of the storm (e.g., vehicles), the remaining damage will be the same regardless of forecast accuracy. So where are the billions in savings if we can’t just make storms go away? I’m honestly confused about this.

This is a good question that I don’t think we do a good job really showing and explaining. We just kind of state it because we know it but we never tell people *why.* So, here’s a short explainer. Preparing for significant weather involves a significant amount of resources. You have to really think hard about some of it, but consider: Ahead of a hurricane, you need extra staffing, you need shelters, evacuations, decisions by individuals regarding evacuation and whether to get a hotel, businesses closing or losing business due to evacuations or just inclement weather. And if predictions of that are incorrect, that can cost companies, small businesses, individuals hundreds, if not thousands of dollars. For larger companies making decisions around energy procurement or logistics or supply chain or additional preparations ahead of a forecast weather event (or even just a heat wave or cold snap), that can be tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not more. Weather will happen regardless, yes, but preparing and budgeting for the impacts of weather adds up dramatically when you extrapolate it out nationally. A good forecast can save thousands of dollars or more. A bad forecast can cost thousands of dollars or more, so you definitely can layer on those costs vs savings quickly. I’ll provide a couple links with explanations on studies that show how this can be quantified more appropriately than me just being hand-wavy. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/impactevaluations/economic-benefits-weather-forecasting from the World Bank, here’s an article on the number of lives saved or that could be further saved with forecast improvements: https://www.knkx.org/national/2023-07-12/should-we-invest-more-in-weather-forecasting-it-may-save-your-life, here is more of a global perspective, but you can extrapolate this to the US economy and assume it is significant: https://wmo.int/media/news/new-study-shows-socio-economic-benefits-of-weather-observations I think when you talk about budget cuts, you need to talk about where you can get your bang for the buck in terms of savings. Cutting from NOAA is probably not going to provide any meaningful savings you’re seeking if you’re managing a budget, and it may actually work against the calculus. And I think that’s the real take home here.