One-sentence summary

Today’s post primarily dives into where we stand with El Niño currently and what sort of impacts that could have heading into winter.

Tropics: Quiet!

We’re all quiet out there at the moment in terms of anything meaningfully developing in either the Atlantic or Eastern Pacific basins. It should be a quiet week overall.

U.S. Weather: Warmth taking hold

Overall, it should be a relatively calm week across the country. We are not expecting too much in the way of severe weather or excessive rainfall this week. One could argue that there’s at least some interesting weather happening though. A storm today and tomorrow will bring more rain and mountain snow to the Pacific Northwest. Another may follow toward the weekend. Overall, these systems look relatively minor on the atmospheric river scale this week.

A pair of systems will bring rain and snow to the Great Lakes and southern Canada through the week. And a relatively strong system will bring showers and thunderstorms to portions of Texas later this week. There should also be a rather significant winter storm in southern Alaska later this week as well.

Temperature-wise, it looks like a very warm week nationally. Multiple record highs will be threatened from the Southern Rockies to the Carolinas this week, including close to 20 tomorrow.

Not terribly cold in most of the country.

Updating El Niño: It’s here and still strengthening

To this point, I don’t think I would describe the behavior of the current burgeoning El Niño as “classic” in many ways. It’s basically already a “strong” El Niño event, and while its influence is there it is not complete just yet. For example, if you look at just sea-surface temperatures in what we call the El Niño box in the tropical Pacific, the current event ranks about 7th strongest since 1950 (based on the Oceanic Niño Index, or ONI).

However, if you look at another dataset called the Multivariate ENSO (El Niño) Index, or MEI, this event is only the 9th strongest since 1979 (which is probably around the 14th or 15th highest since 1950). Why am I sharing these data points with you? Well, the ONI is looking purely at ocean temperature. The MEI is typically a better index in that it factors in other variables, which we would liken to how the atmosphere is responding. So the ONI can be a proxy for ocean response, whereas the MEI can be a proxy for atmospheric response. To this point, the atmosphere has not yet responded to the same extent as the ocean has.

But that may finally be changing. I shared the chart above showing the sea-surface temperature anomalies in the various different El Niño regions of the Pacific to highlight the differences between the 1+2 region (bottom panel, which is the eastern Pacific) and the 3.4 region (2nd panel from top, which is closer to the International Dateline.). The eastern Pacific has been revved up since spring. The central Pacific took a bit longer, but it finally appears to have hit a level where it should allow for El Niño to become the more dominant feature for global weather.

And if anything, this event is likely to intensify further in the next couple weeks. So if you’ve been wondering if this El Niño was going to show up like a typical strong El Niño, there may be reason to assume it will.

What does that mean? No relationship is perfect, but in general, El Niño has a decent correlation to a couple key elements here in North America.

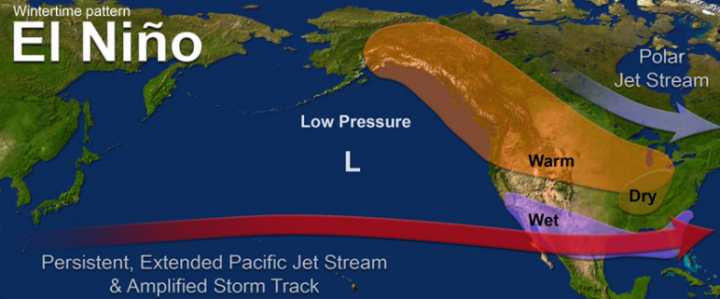

Generally, we see a cooler, wetter Southern U.S. and northern Mexico, as well as a milder Canada and northern tier of the U.S. into Alaska. Usually more storms will crash into California during El Niño winters. Sometimes, like in 2015-16 that isn’t the case. But on average, it is. Seasonal climate models are fairly confident in a warm North/cooler South but a bit split right now in terms of how they view precipitation. An American climate model, the CFS, shows a rather classic wet California and wet Texas through Southeast. The European model has the second part but shows near-normal to just slightly above average precipitation in California.

The bottom line at this point is with El Niño strengthening, one should expect the atmospheric response to also strengthen over the next couple months. And with a rather strong El Niño in place, that response would probably look similar to what is typical in El Niño as shown above. Of course, there are risks as noted, as well. I also think there are wild cards.

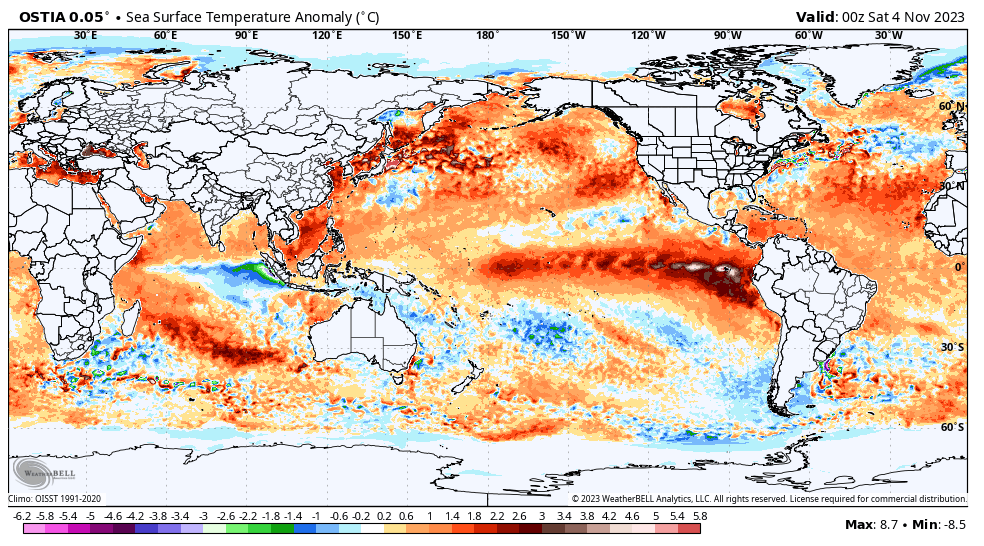

If you look at sea surface temperatures around the world right now, virtually all Northern Hemisphere oceans are warmer than normal.

Why does this matter? We are in a bit of uncharted territory. One of the big reasons El Niño is such a big deal is not just because where it occurs is so important to global weather but also because it’s often so anomalous relative to other global sea surface temperatures. It becomes a dominant feature. Well, what happens when you trigger an El Niño on a planet with a lot of oceanic temperatures that are also extremely warm, relative to average? We’re going to find out this winter. While the smart money is probably still on El Niño leading to El Niño things, there is at least some chance the typical impact could be perhaps a bit muted because the majority of the planet is so much warmer than normal. Would I bet on that? No. Am I watching it as a forecaster? Yes.

Suffice to say, we live in interesting times.

I’m just hoping we don’t get a December 2015 or 2021 type of winter this year. High 70s for lows? Yuck!

Great ENSO info – making it more relatable to us – the Eyewall is the Best! 💓

🍂🍂 🦉 🍂🍂

Excellent job Matt. Thanks! Sacrificing a little heat for additional water…so to speak…sounds real good. We are thirsty in GLS.

Does this strong El Niño portend a return to the 2015-2016 big floods in Houston?

Not necessarily. You’d think we would have a wet spring, but that’s not a guarantee either.

Thanks for your insightful commentary. For our area in west central Florida the prospect of a wetter winter is hopeful. We’ve been very dry due to a predominately westerly wind pattern for most of this past summer.