In brief: Today, we reflect on the 1900 Galveston hurricane, which made landfall on this day 125 years ago. The lessons before and after the storm ring loudly today in an age where disaster is happening to more people more frequently.

On July 16, 1891, a byline in the Galveston Daily News attributed to Dr. Isaac Cline was published. The sub-headline read “Record of twenty years — The Texas Coast Not Liable to Serious Damage.” Essentially, Cline was using the best knowledge of how things worked at that time to try to explain why he believed the Upper Texas Coast was immune to disasters, such as the 1875 Indianola Hurricane.

After seeing what happened to Indianola in 1875 and again in 1886, some residents of Galveston had felt they needed a seawall for protection of the city. Cline, among some others did not believe this was necessary. In fact, in this 1891 article, Cline wrote this:

The opinion held by some, who are unacquainted with the actual conditions of things that Galveston will at sometime be seriously damaged by some such disturbance is singly an absurd delusion and can only have its origin in the imagination and not from reasoning; as there is too large a territory to the north which is lower than the island over which the water may spread, it would be impossible for any cyclone to materially injure the city.

While it may seem patently absurd today that any learned individual would ever say something like that with such confidence and in that tone, keep in mind again the context of the day. This was not a deranged individual. This was how even brilliant people thought about things in that era. But in hindsight, it tells us a lot about hubris and an invincibility complex.

The storm

It was today 125 years ago that hell was unleashed on the Texas coast. The great Galveston hurricane remains the deadliest single weather event in our nation’s history. Despite how it may seem in hindsight, it wasn’t inevitable. And despite it happening 125 years ago, it remains as relevant today as it was in 1900. Most of us know the general theme of things. The hurricane struck Galveston, delivering the full fury of the Gulf of Mexico onto the island, washing away virtually every structure on the Gulf side of the island. The death toll ranged from 6,000 to 12,000 based on various estimates. The storm’s impact was well documented in several books. Obviously, “Isaac’s Storm” comes to mind first and foremost, telling the story through the life of the weather bureau chief in Galveston, Isaac Cline. “A Weekend in September” remains a classic for this topic as well. I am fortunate to also own an original copy of the “The Great Galveston Disaster,” which contains accounts and details of the storm’s impacts.

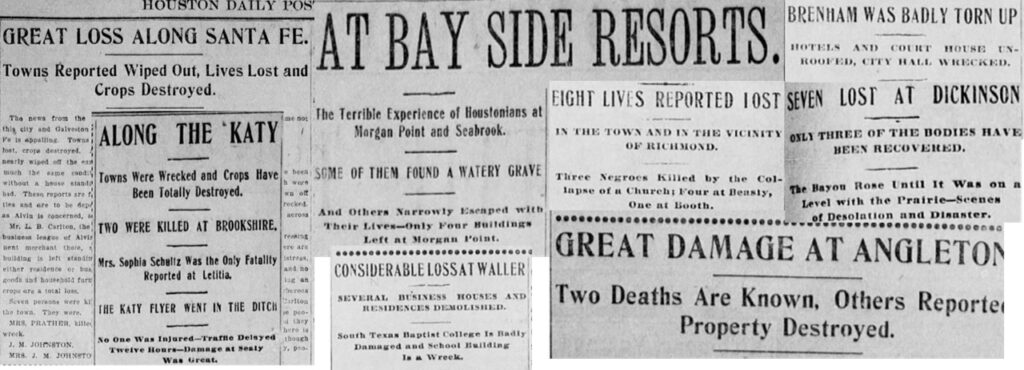

But the Galveston storm also had noteworthy impacts near and far from Galveston.

Across Southeast Texas, damage was everywhere. Bayshore communities were devastated with significant loss of life. Inland locations from Houston to Richmond to Brenham suffered extensive, widespread damage and lesser but not inconsequential loss of life. A similar storm today, a large category 4 hurricane would probably cause north of $100 billion in damage, with significant risk to the Houston Ship Channel, an economic engine for both Texas and America.

The 1900 storm remained a tropical storm into Oklahoma before it became post-tropical. But the 1900 storm was clearly fueled by the jet stream after that, and it reintensified as an extratropical cyclone over the Midwest and Great Lakes.

As the storm moved into the Great Lakes it produced wind gusts over 80 mph in Chicago, 78 mph in Buffalo, and 74 mph in Toronto. Flooding occurred in Minnesota, two were killed in Chicago, and “severe damage” was reported in Buffalo.

As it passed north of an extremely dry New England, it helped fuel significant wildfires that broke out in southeast Massachusetts and Cape Cod.

Water scarcity had been a problem in 1900 in New England, with shortages reported in New Hampshire and Connecticut. The passing of the hurricane, with drier air on the back side and gusty winds led to a rough setup that helped produce fires.

In Canada, the damage was immense in the Maritime Provinces with strong winds and numerous shipwrecks. Over 50 were confirmed killed in Canada, making the 1900 storm the 8th deadliest storm on record there. However, unofficially, the toll was likely higher, and the 1900 storm may be as high as the third deadliest (possibly over 200 perished).

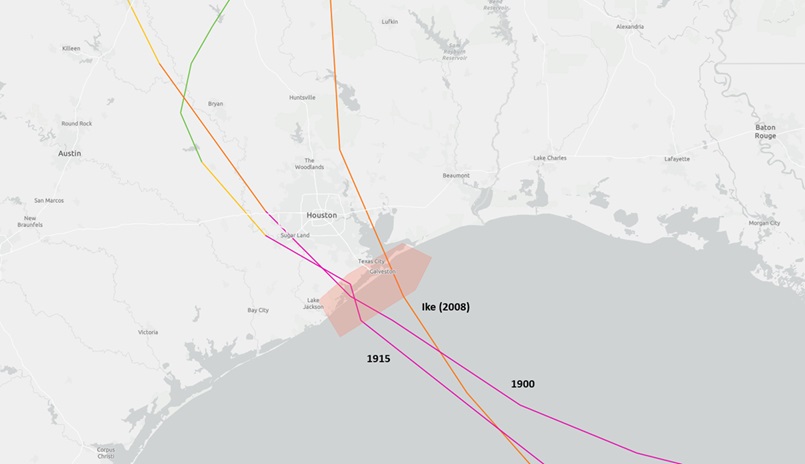

The footprint was massive, and in 2025, this type of storm may not cause as much loss of life but would still cause immense damage. We got a sampling of this with a similar storm to the 1900 storm, Hurricane Ike in 2008. Ike caused over a half-billion dollars in damage and wind gusts of hurricane-force inland across interior parts of the U.S.

Response to 1900

Recall at the beginning of this post, we noted how the 1875 Indianola hurricane planted the seed that never germinated in time. After the storm, the reaction was quick. The Seawall began construction in 1902 with the first segment completed by 1904. The length was over 3 miles. An additional extension just under a mile was completed in 1905 to protect Fort Crockett. The first three miles were approved by the Texas Legislature and funded by the issuance of bonds in Galveston County. The section protecting the fort was funded by Congress. The Seawall was further extended in 1927 and again in 1963. In addition to that, 500 city blocks were raised in elevation by 1911. This was the largest civil engineering project in American history at that time and stands as one of the most enduring.

The Seawall paid dividends almost immediately. In 1915, a very similar storm to the 1900 one struck nearly the same exact place. We’d be the first to tell people that no two storms are identical, but in this instance, the difference was so dramatic, it needs mention. While the 1915 storm did do a fair bit of damage, the devastation that was seen in 1900 was not repeated in any way. The loss of life was around a dozen in Galveston proper, with many others lost elsewhere on Galveston Island and along the bayfront closer to Texas City. But the Seawall stood the test. It was the true definition of hazard mitigation.

When Hurricane Ike hit in 2008, the damage in Galveston proper was primarily caused by bayside flooding, as Ike took a slightly farther north track. The Coastal Barrier project, or “Ike Dike” as it’s commonly called would substantially mitigate this type of flooding, further bolster the Gulf side risks, and provide a layer of protection that does not currently exist for the Houston Ship Channel.

The 1900 storm still matters a lot today for the toll it took and the lessons it left behind

I’ll say it again: Hurricane Ike hit the Texas Coast in 2008. 17 years later, the Ike Dike is a plan on paper that’s funded sort of, but not really. After 1900, the people of Galveston recognized what had to be done and did it. It’s a different world today of course, and these projects are more complicated, more thorough in planning, done more safely, and they’re just more expensive. But here’s the thing about large mitigation projects: They save more than they cost. The Galveston Seawall is a testament to that. It was created as a reactive solution to a permanent, existential problem. What has it done? Saved hundreds of millions of dollars in damage and countless lives. Will the Ike Dike do the same thing? The better question may be: Would the Seawall have prevented the 1900 tragedy? The answer is probably yes, even if in truth, there’s no way to know for sure. But the plans for the Ike Dike seem reasonable, and we know that mitigation money pays back about $6 in avoided damage for every dollar invested.

Ingenuity and a sense of existential risk to a community brought people together after 1900 to plan and implement a radical change. As we move forward through the 21st century, we are going to need that same sense of thinking for the greater good of our communities. It’s likely that some communities will face existential threats to their survival, be it through sea level rise, storms made worse by warming oceans, or simply infrastructure that’s unfit for the current population. These risks aren’t unknown. We know what many risks to our communities are; they aren’t theoretical. Had Galveston followed down that line of thinking in the 1890s, the 1900 storm may have been a footnote in history. The lesson from 125 years ago stands today: Proactive investment in hazard mitigation for our communities allows them to survive and prosper, and that’s good for everyone.