In brief: The potential for significantly impactful coastal storm continues from the Carolinas to perhaps as far north as New England, with significant marine and beachfront impacts becoming more likely. Tropical Storm Jerry is disorganized this morning, but it will take a swipe at the far northeast Leeward Islands tomorrow night or Friday, perhaps while becoming a hurricane. Meanwhile, the potential for significant rainfall in the Southwest, courtesy of the remnants of Hurricane Priscilla continues to look high beginning Friday.

East Coast coastal storm

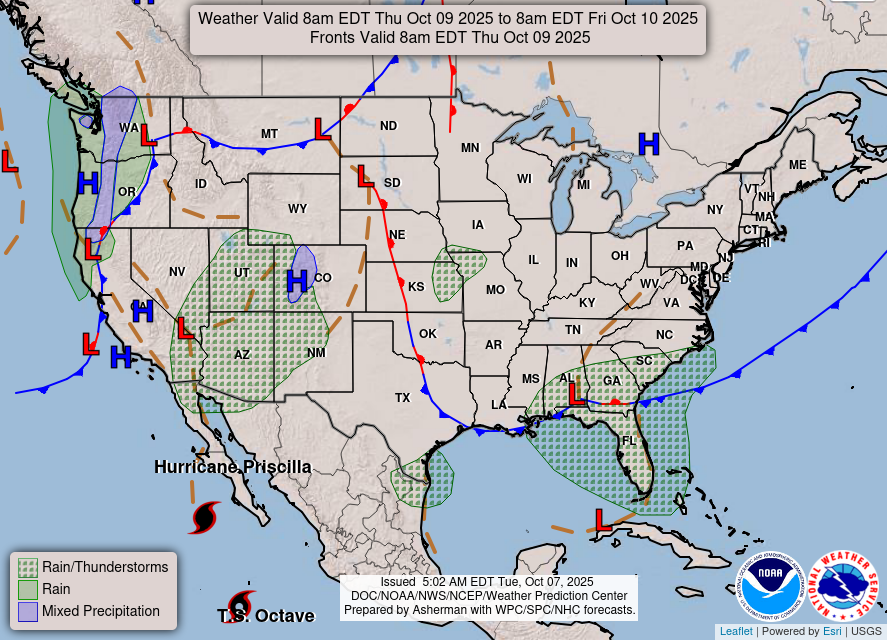

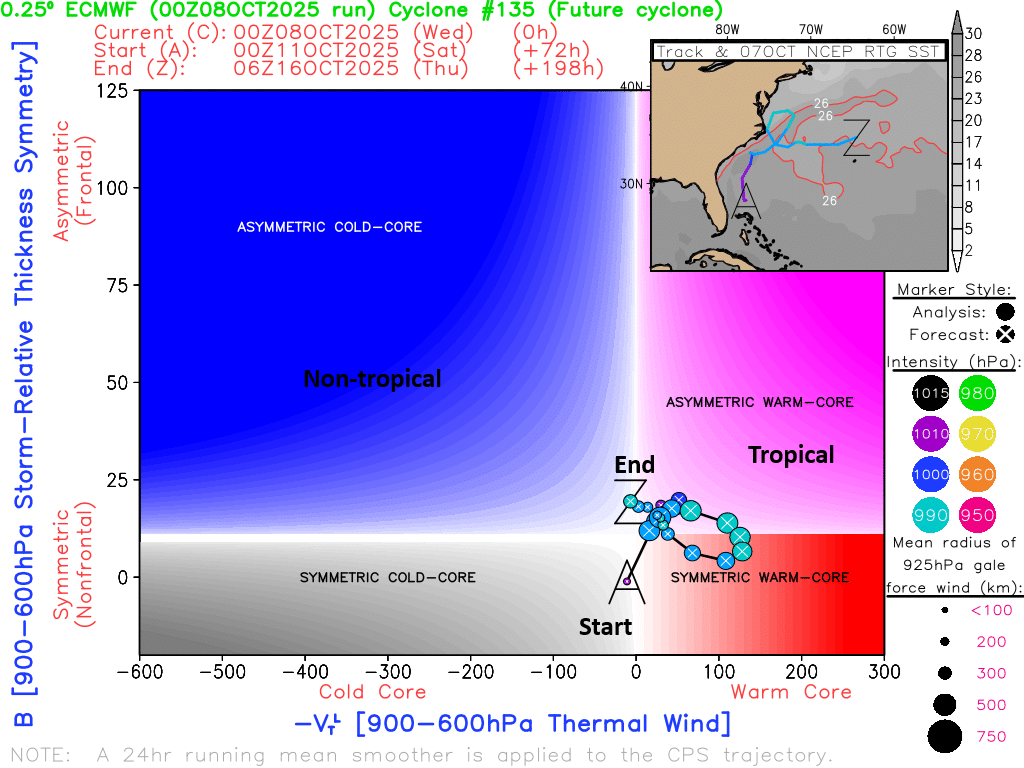

We’ll start today again with the latest on a likely coastal storm that will taunt the Eastern Seaboard from the Carolinas to perhaps New England from Saturday into early next week. There still remain numerous questions on track, intensity, etc., but a few updates today. First, again to be clear, this will not begin as a tropical system. This is going to be like a winter nor’easter (minus the snow) in terms of how it develops. As it interacts with the warm water off the Carolina coast, it could begin to take on a “flavor” of a tropical-type system.

We typically would call this potentially a subtropical storm, and if that’s the case it will get a name (Karen; go ahead, make your jokes now. Sorry to all Karens).

All that said, the main point: Name or not, the impacts will be virtually the same on the East Coast regardless.

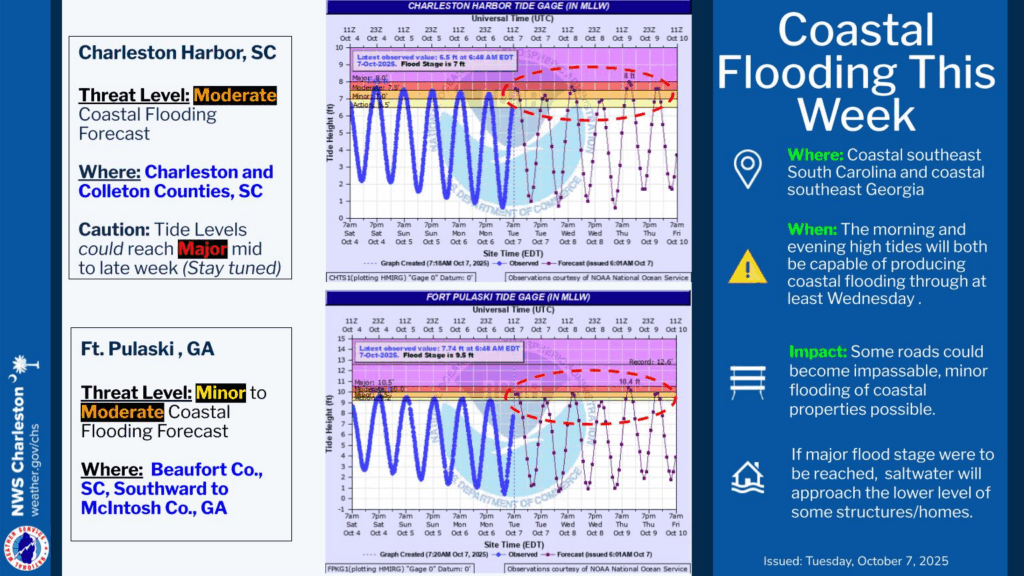

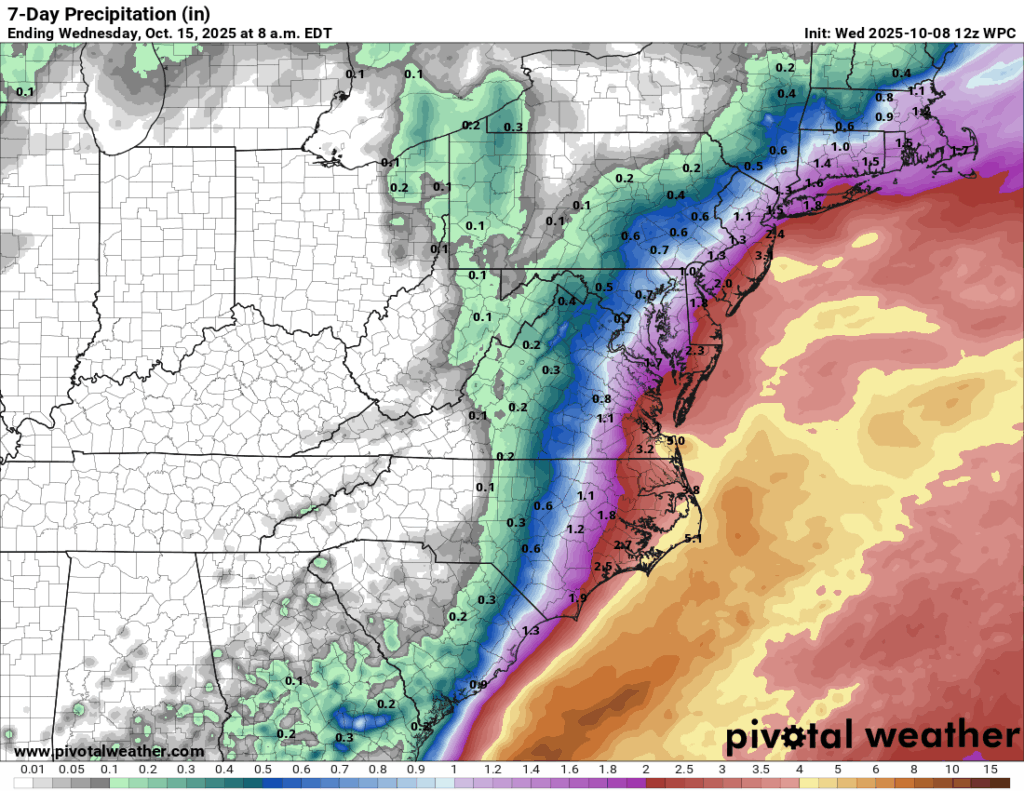

So, now that we know not to focus on the name or “type” of storm it is, what will the impacts be? Well, that’s going to depend on track. A few things seem likely: Rough surf, potential for beach erosion, some element of tidal flooding, gusty winds on the coast. What are we unsure of? How strong will the winds be? Will they make it farther inland? How severe will tidal flooding be? Which location will experience the worst conditions? How long will this last? Who sees the heaviest rainfall?

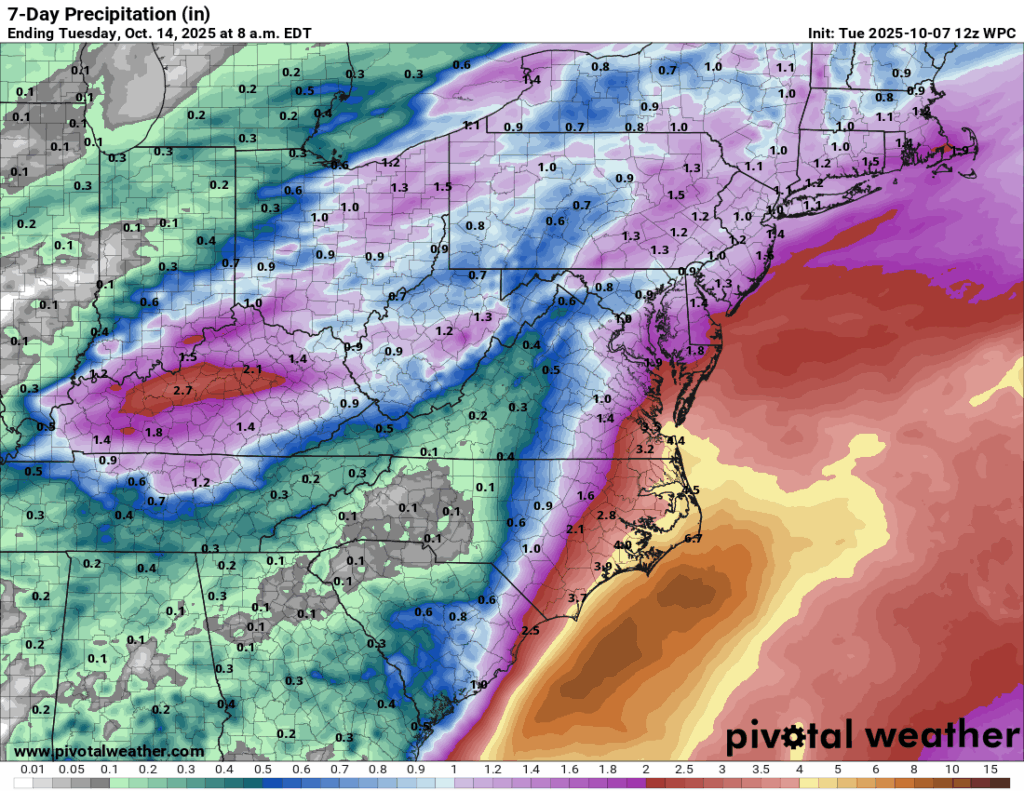

Various models show various solutions at this point. The high-level thinking right now is that a surface low will form off the South Carolina coast on Friday and Saturday, work northward, perhaps close to Long Island or off the Jersey Shore by Monday, then either drift east out to sea, or drift back south toward North Carolina and then out to sea. Although none of this is set in stone, one thing we can say is that this could potentially be a long-duration event for folks, meaning multiple high tide cycles worth of impacts from the Outer Banks to the Jersey Shore or possibly Long Island and New England.

Folks on the beachfront will want to prepare for several days of potential inconvenience, including tidal flooding and potentially significant beach erosion. Additionally, heavy rain on the immediate coast could exacerbate tidal flooding issues as well. Wind could be on the order of 40 to 60 mph in gusts on the coast, which could cause some damage as well, particularly when considering the potentially extended duration of winds.

Bottom line: A significant, complex, tricky to forecast specifics storm is coming this weekend from the Carolinas through New England.

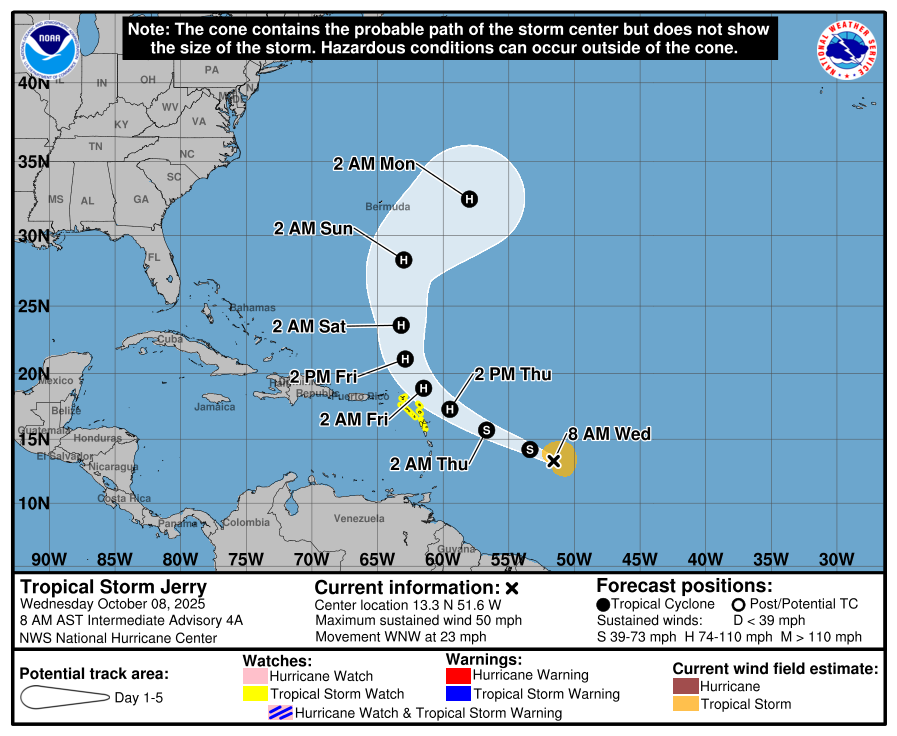

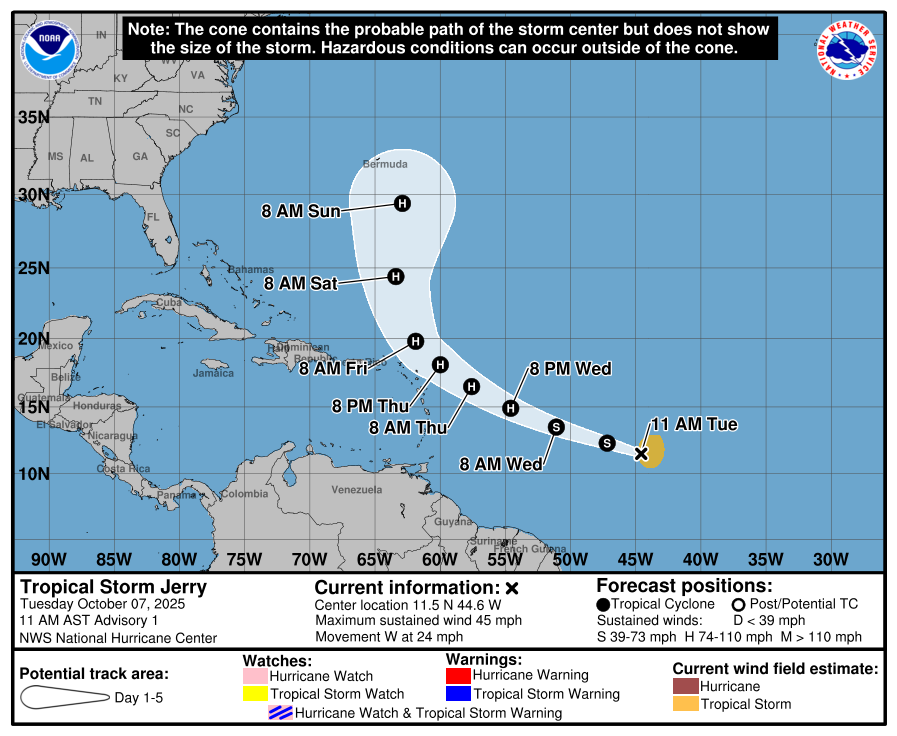

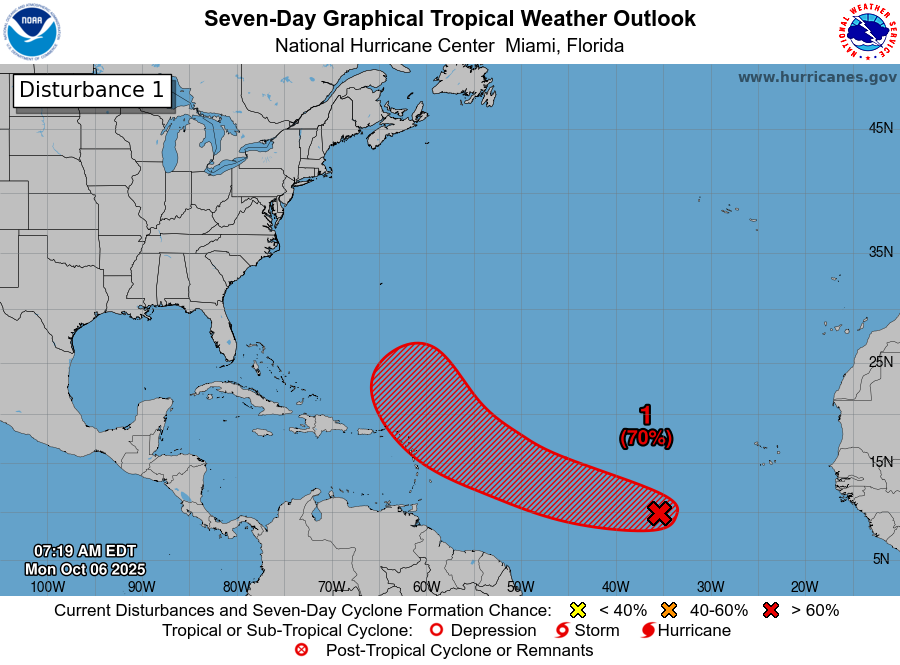

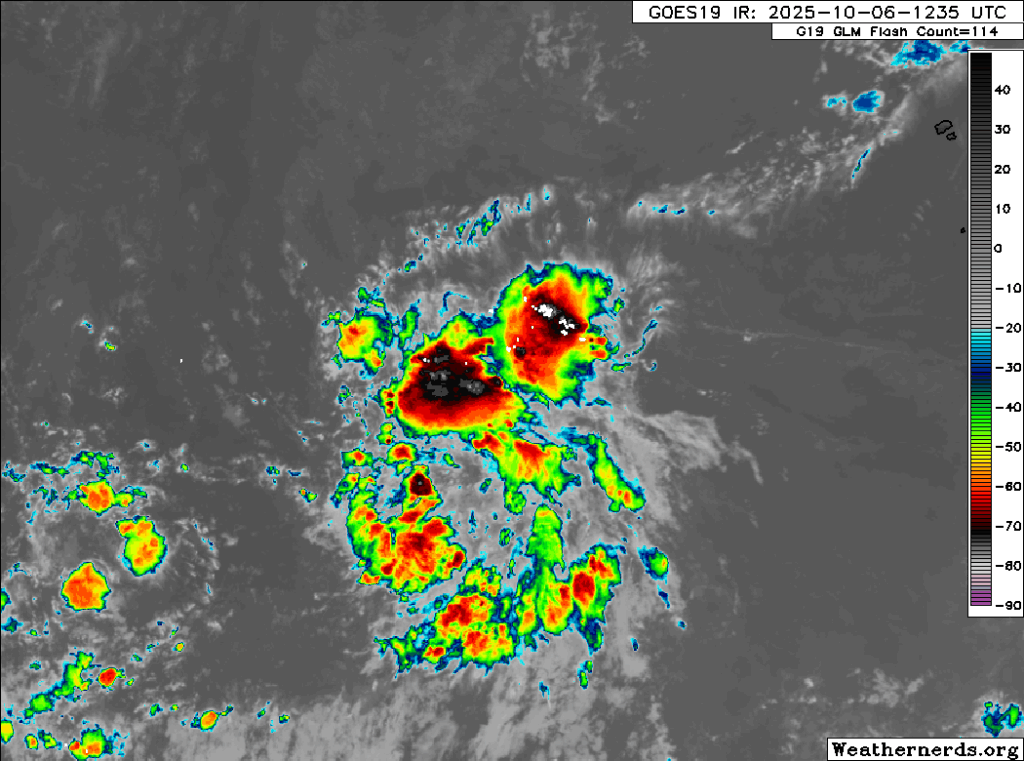

Tropical Storm Jerry

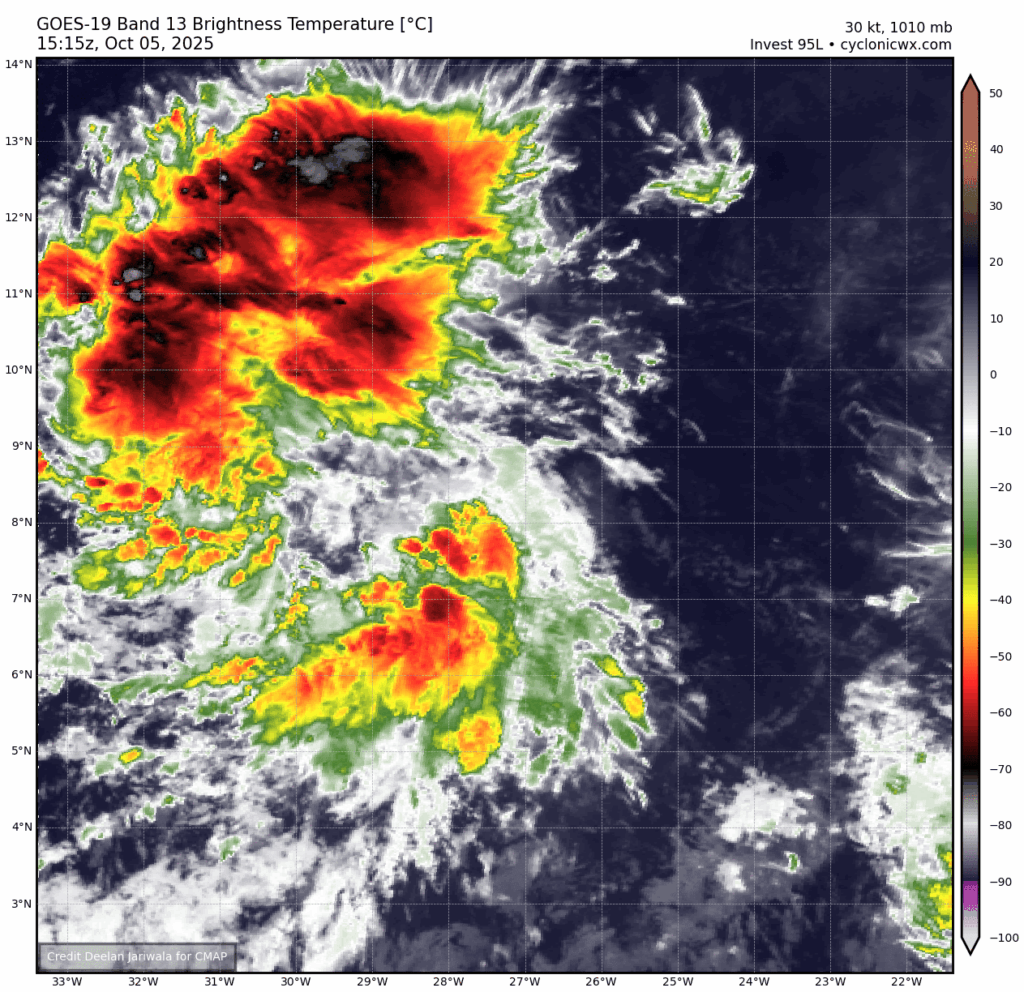

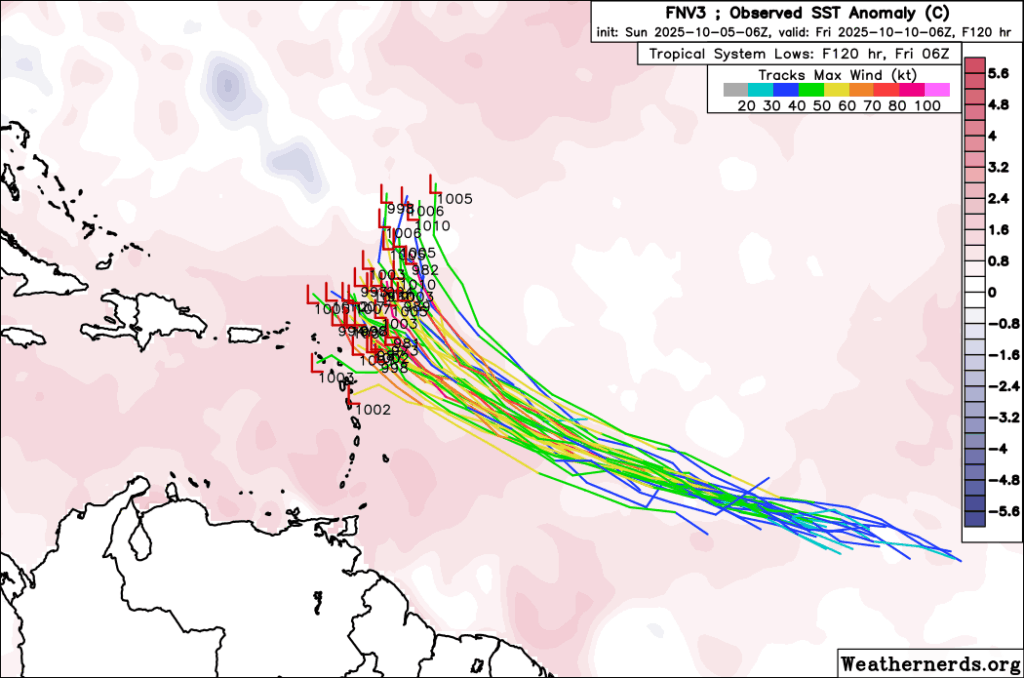

Jerry is struggling this morning, as wind shear takes some toll on the system. It frankly looked a bit better yesterday.

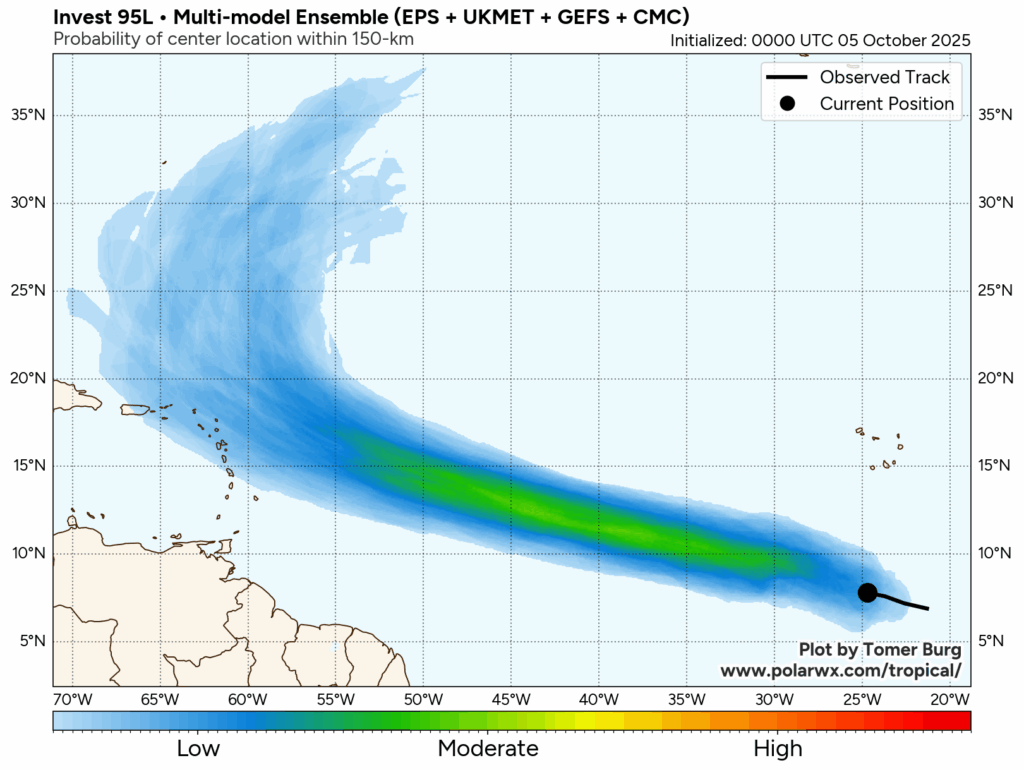

Jerry will begin approaching the northeast Leeward Islands on Thursday afternoon. As it does so, it will slow down, preparing to turn more northward. As this happens, the storm should begin to put itself together better, which will lead to a burst of intensification. Because of the close proximity of the forecast track of Jerry and the likelihood that the storm will strengthen, a Tropical Storm Watch has been issued for a pile of islands: Antigua, Barbua, Anguilla, St. Kitts & Nevis, Montserrat, St. Barthelemy, St. Martin, Saint Maarten, Saba, St. Eustatius, and Guadeloupe.

The NHC forecasts Jerry to become a strong category 1 hurricane, which is current stronger than most model guidance shows, a good strategy the way things have gone this summer. At this point, very few models or model ensemble members drag Jerry directly into one of the islands in the northeast Caribbean, but Antigua and Barbuda would be the closest to the center of the storm. Either way, gusty winds, tropical storm conditions, and heavy rainfall are likely in the islands there.

Jerry should turn north and eventually northeast, with decent model agreement right now on a track staying away from Bermuda.

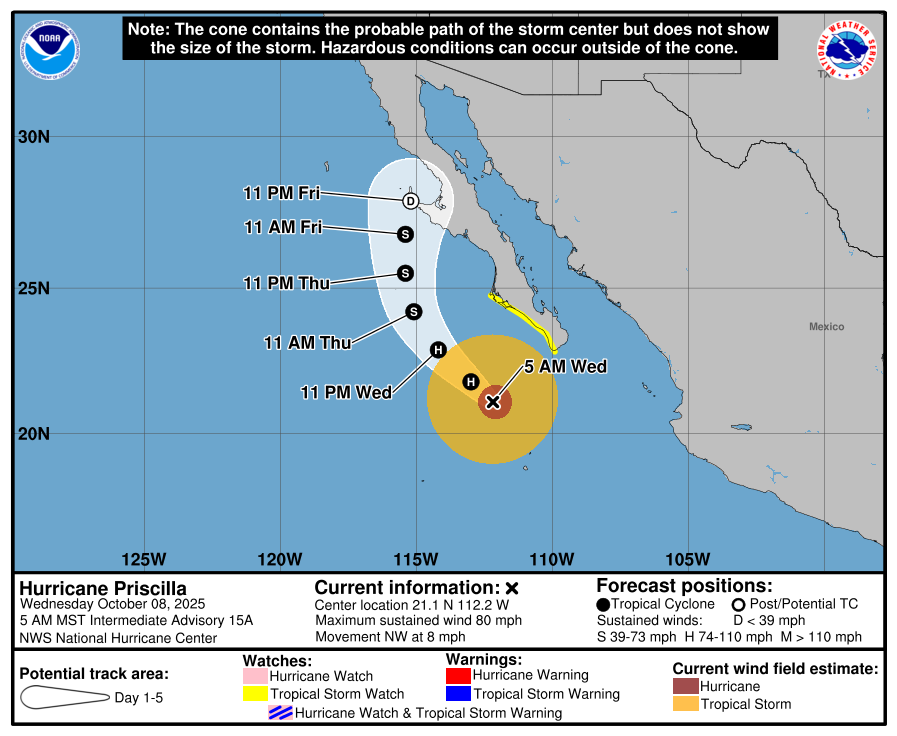

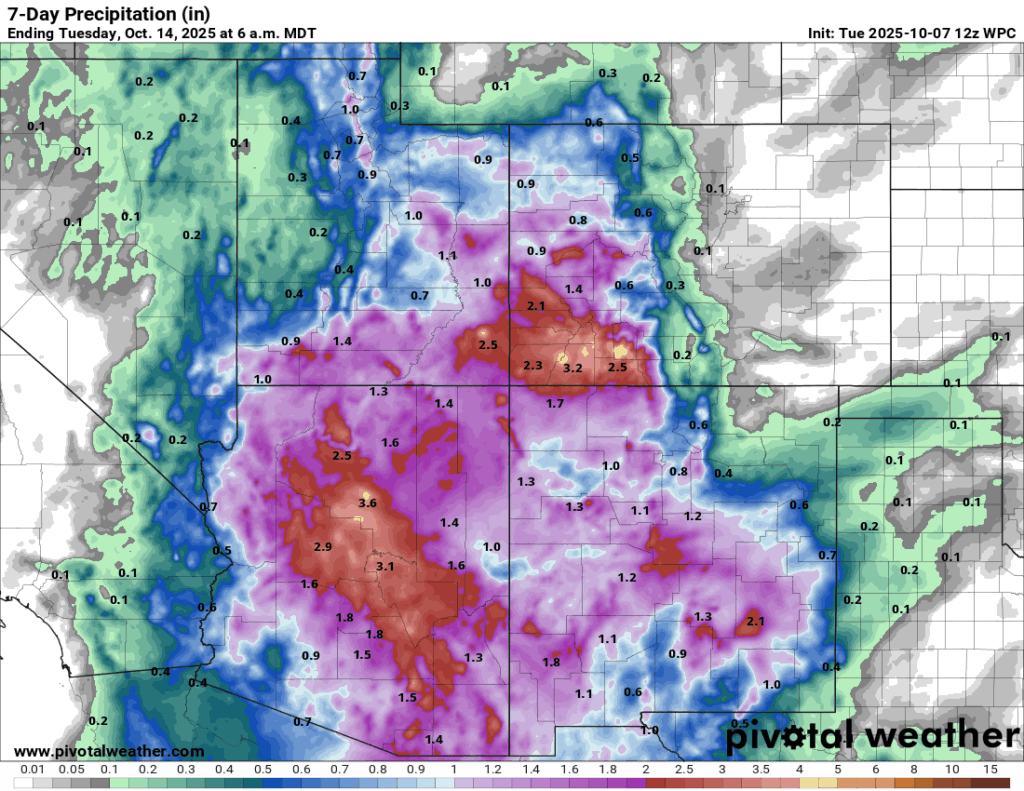

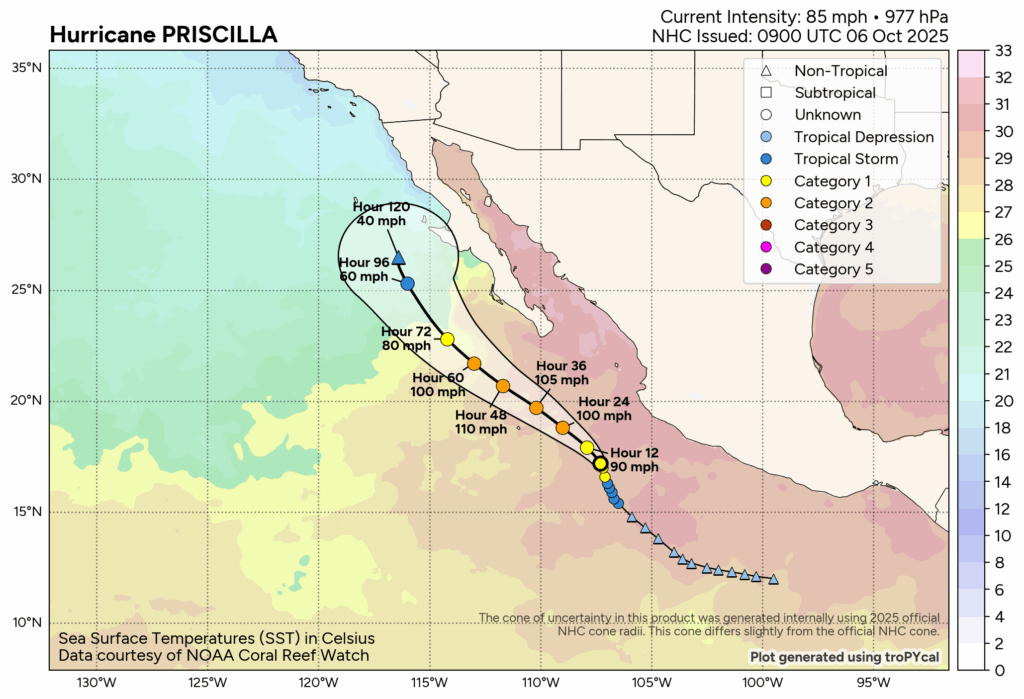

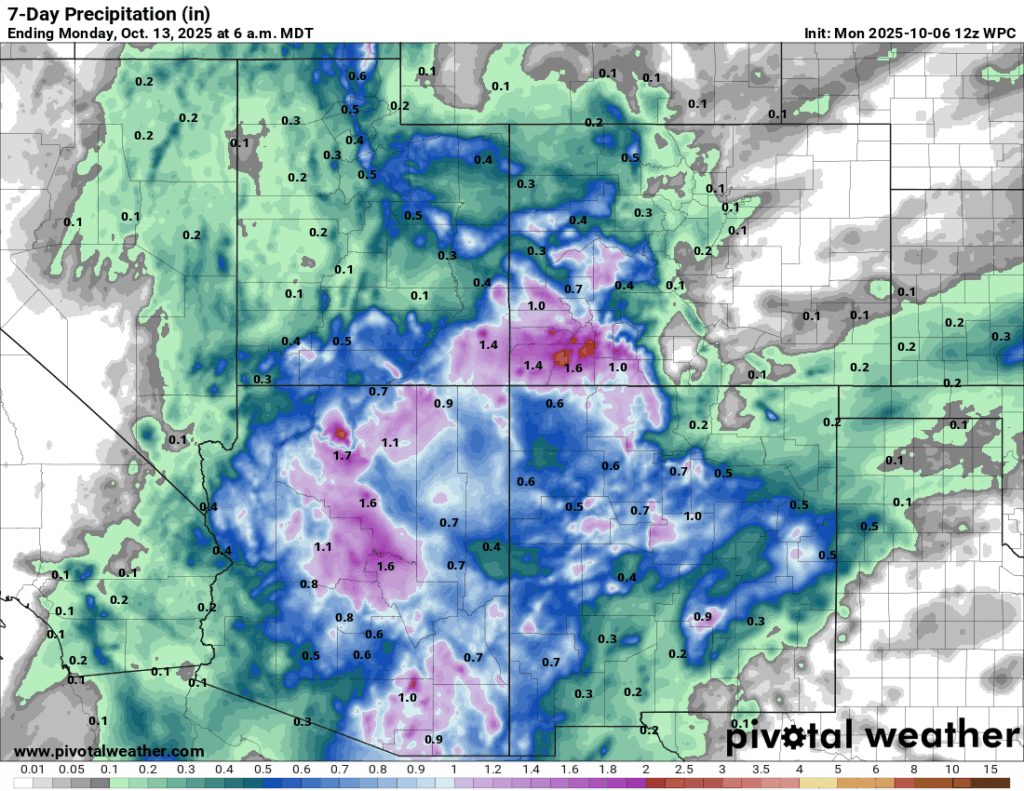

Desert Southwest and Priscilla

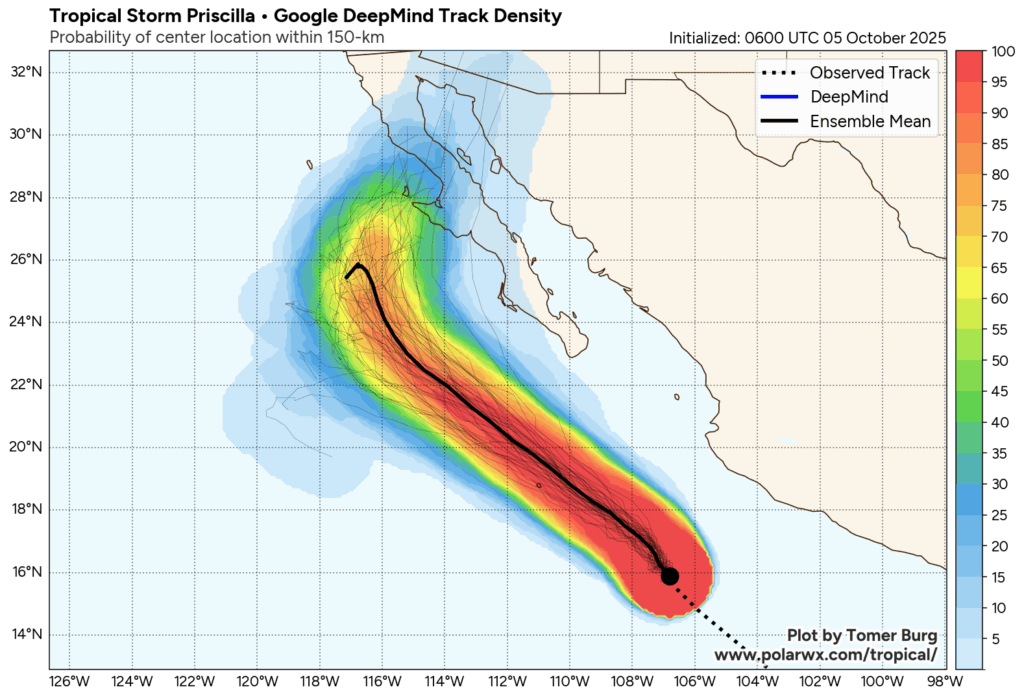

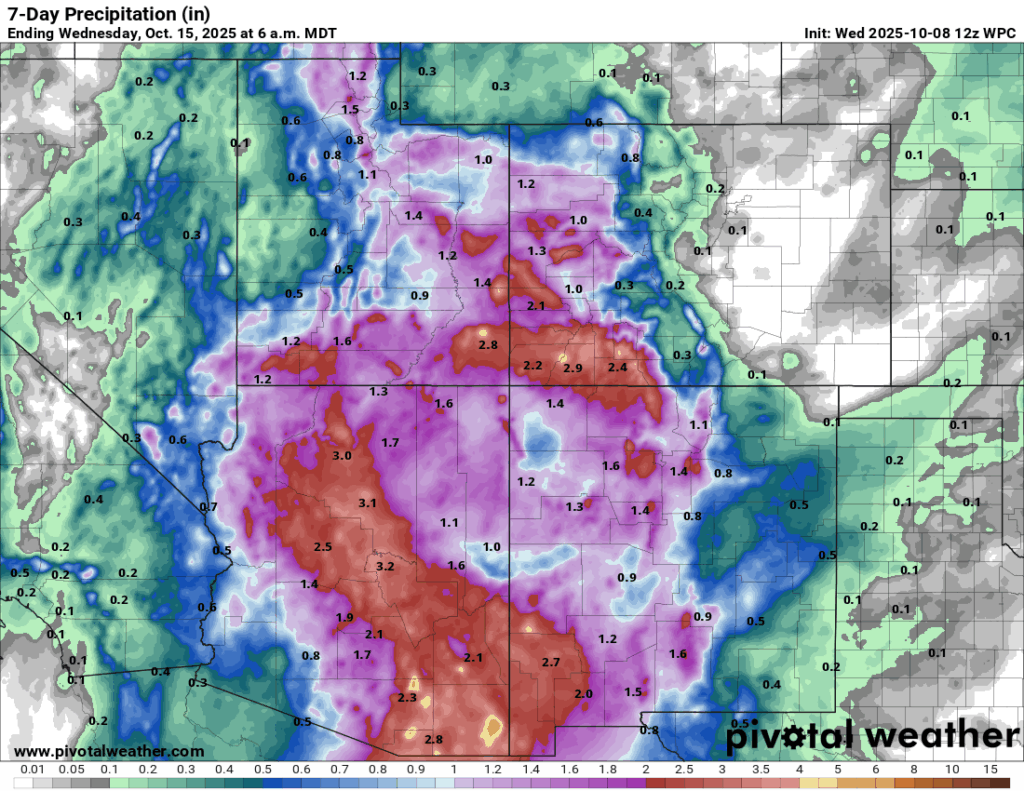

Hurricane Priscilla is weakening after topping out as a major storm. It should be dropping below hurricane intensity later tonight.

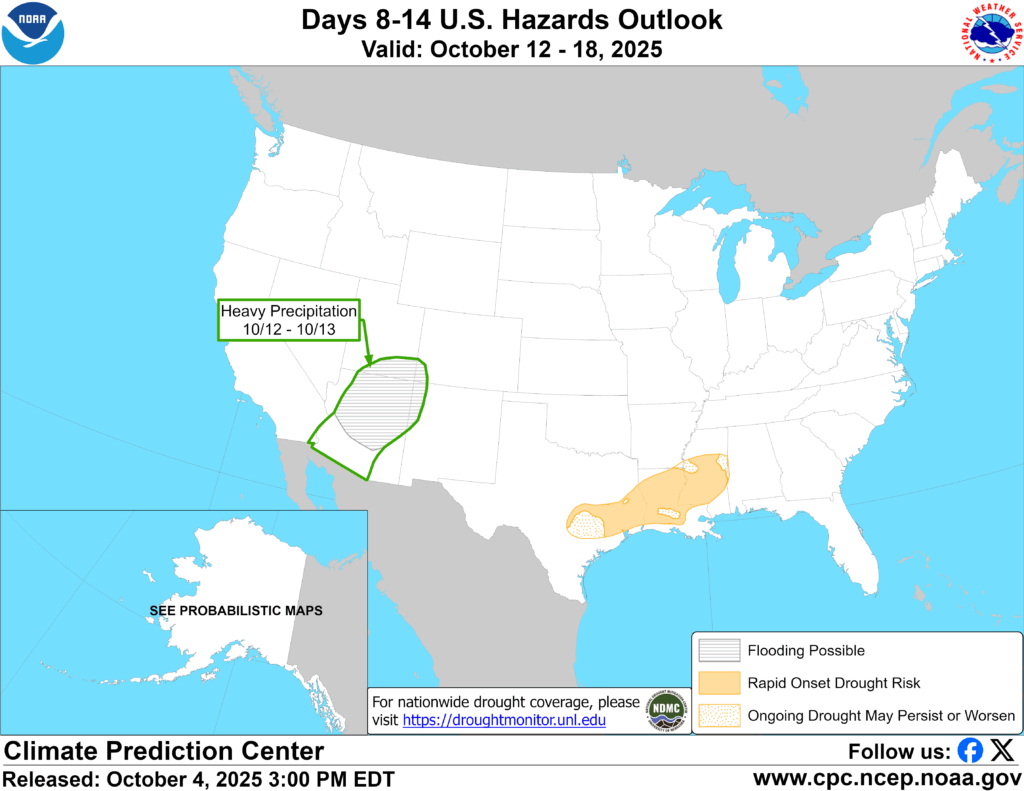

As Priscilla’s remnant come north, they will interact with a rather strong trough that nudges inland from the Pacific, allowing a funnel of moisture to aim into the Desert Southwest. As we’ve been talking about for several days, the potential for locally heavy rainfall is increasing, with slight risks for flooding (level 2/4) now in place from Friday through Sunday in various spots in Utah, Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico.

Some models show potential for even higher amounts than this in localized spots. I would expect flood watches to be posted by tomorrow for much of this region, so while the rain is mostly welcome in the long-term here, this could cause some short-term problems, particularly in Arizona and near the Four Corners.