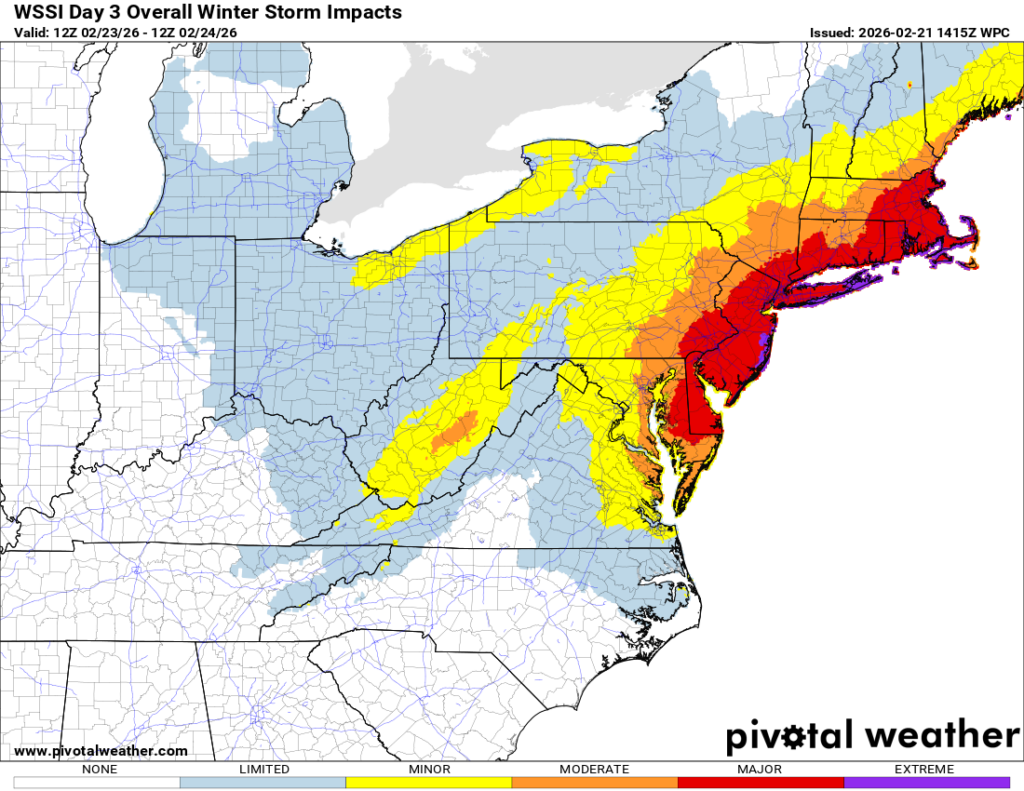

In brief: An extremely impactful winter storm is going to impact the Mid-Atlantic and southern New England beginning tomorrow afternoon and continuing through Monday. Blizzard conditions, powerful winds, heavy snow, and coastal flooding are all part of the mix.

I was having a text message exchange with a friend of mine from New Jersey, and we both agreed that more often than not, it’s the storms that seem to come out of nowhere a day or two before they hit that seem to overperform. And indeed, we’re shaping up to see quite a storm in the Mid Atlantic this weekend.

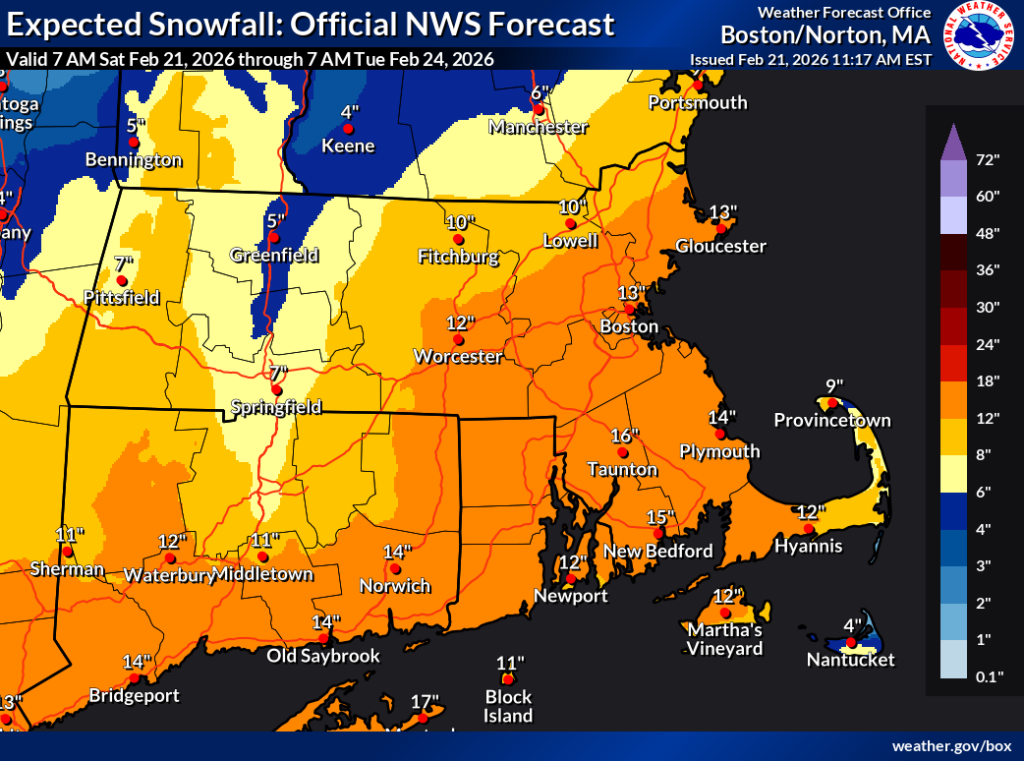

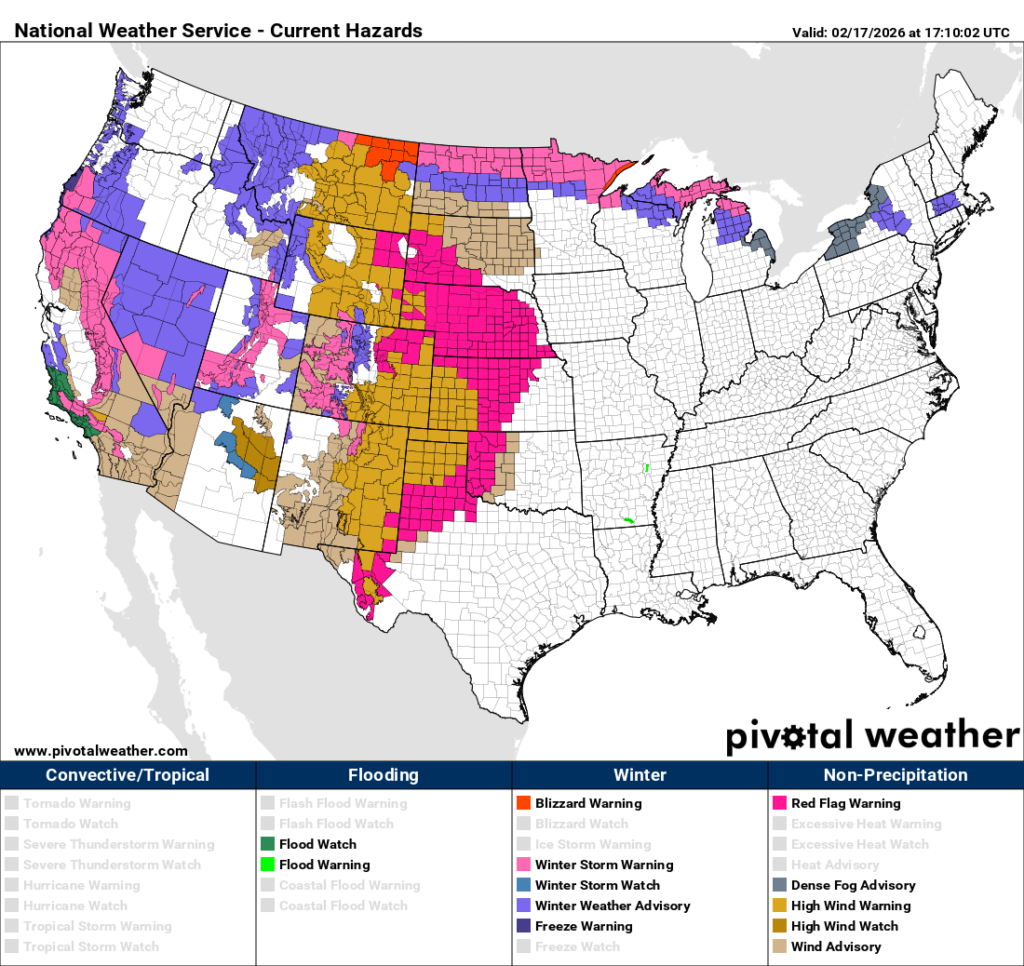

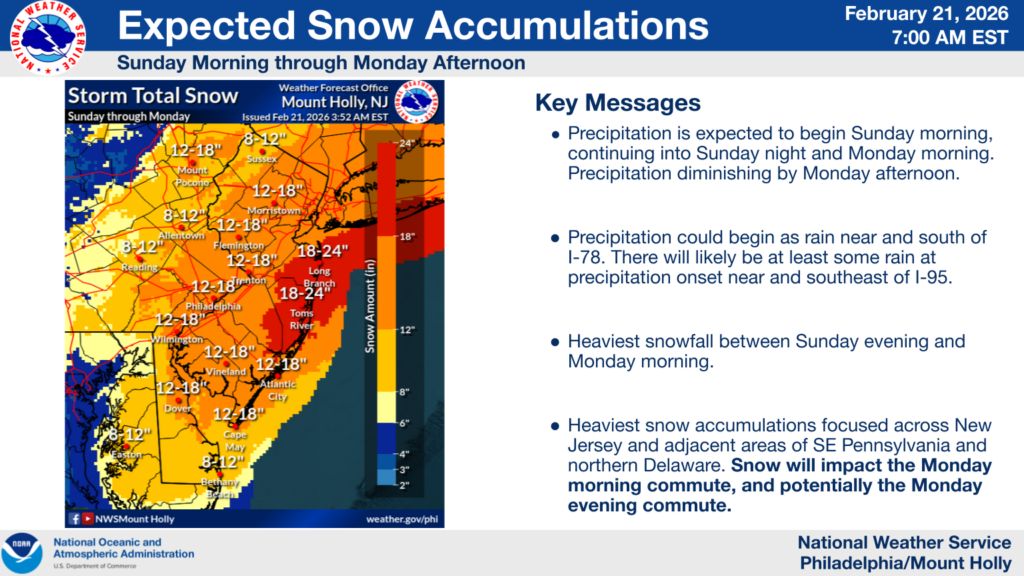

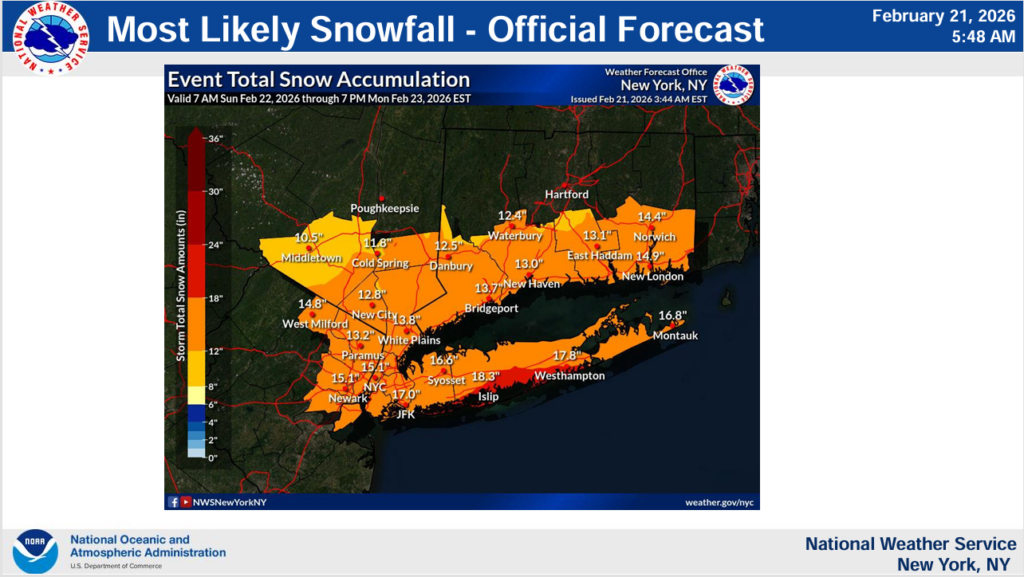

In addition to the impressive snowfall accumulations that are forecast across New Jersey above, Blizzard Warnings are posted for coastal Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut.

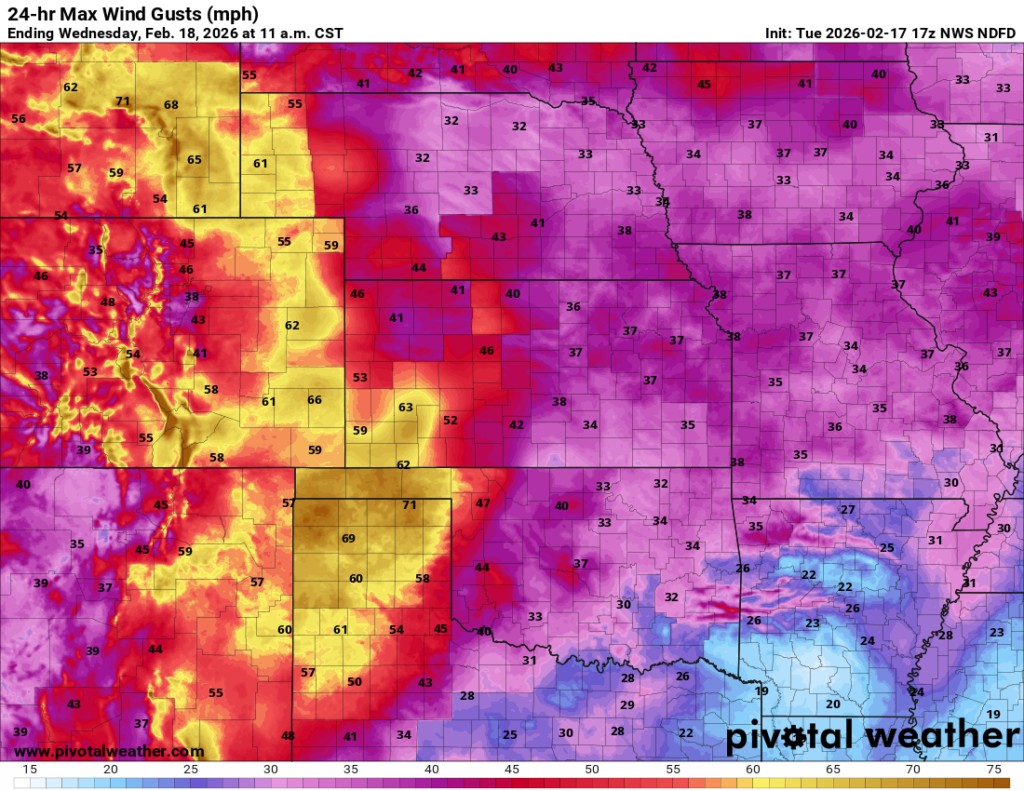

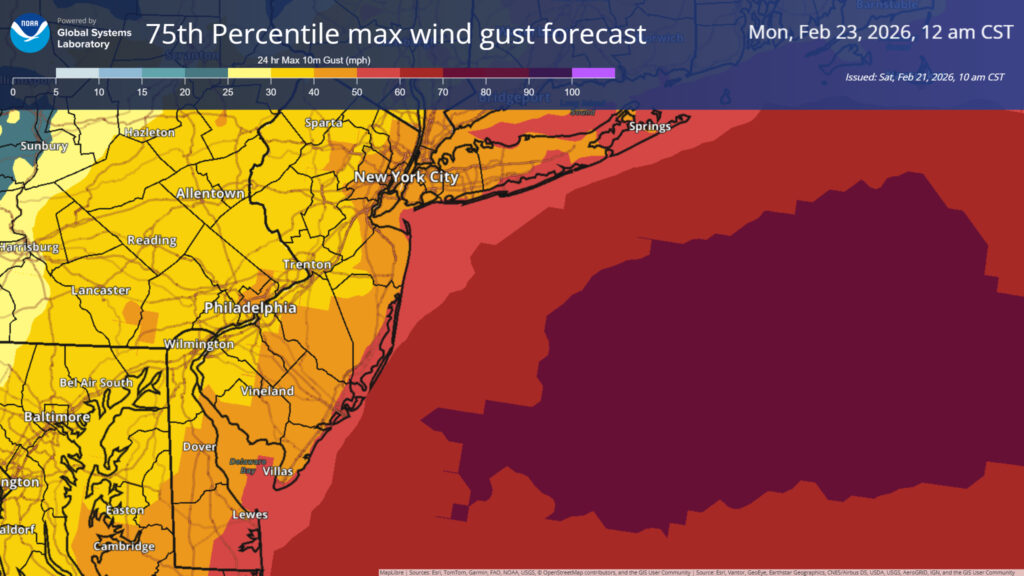

The onset of snow should be Sunday morning, although it may start as rain in many spots. As a South Jersey native, I can assure you that there’s always some uncertainty as to how long it takes for rain to change to snow there, but at present, the models think this will occur by early afternoon on Sunday. From that point, the storm system is going to rapidly deepen off the Jersey Shore and Delmarva, possibly bombing out, deepening at least 24 mb in 24 hours. Regardless, this will lead to the wind cranking out of the northeast. Wind gusts will top off probably in the 50 to 60 mph range, but some higher gusts cannot be ruled out. A good idea to charge your electronic devices on Sunday afternoon in case you lose power.

The storm itself will track toward New England or just off the coast of southeast New England by Monday afternoon.

Heavy snow will expand into New England as well, with significant snow likely in the southern half of Connecticut, Long Island, and Rhode Island.

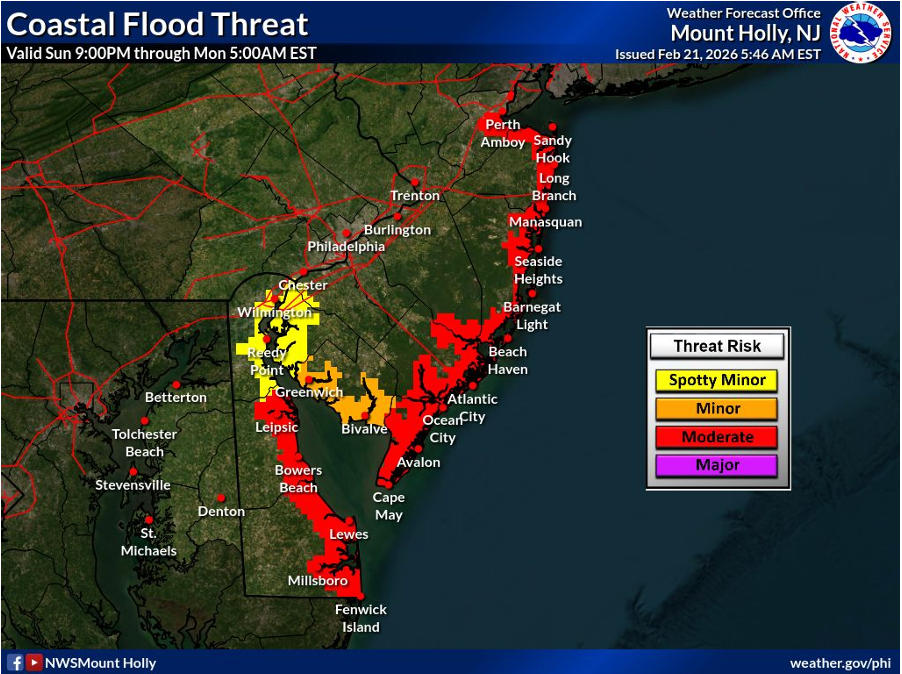

In addition to the snow and blizzard conditions, we will also see some coastal flooding of at least the moderate variety in many areas. The Jersey and Delaware shores will be most susceptible, with a secondary concern into Long Island and southern New England.

Overall, this is expected to be a highly impactful storm from Delaware through New England.

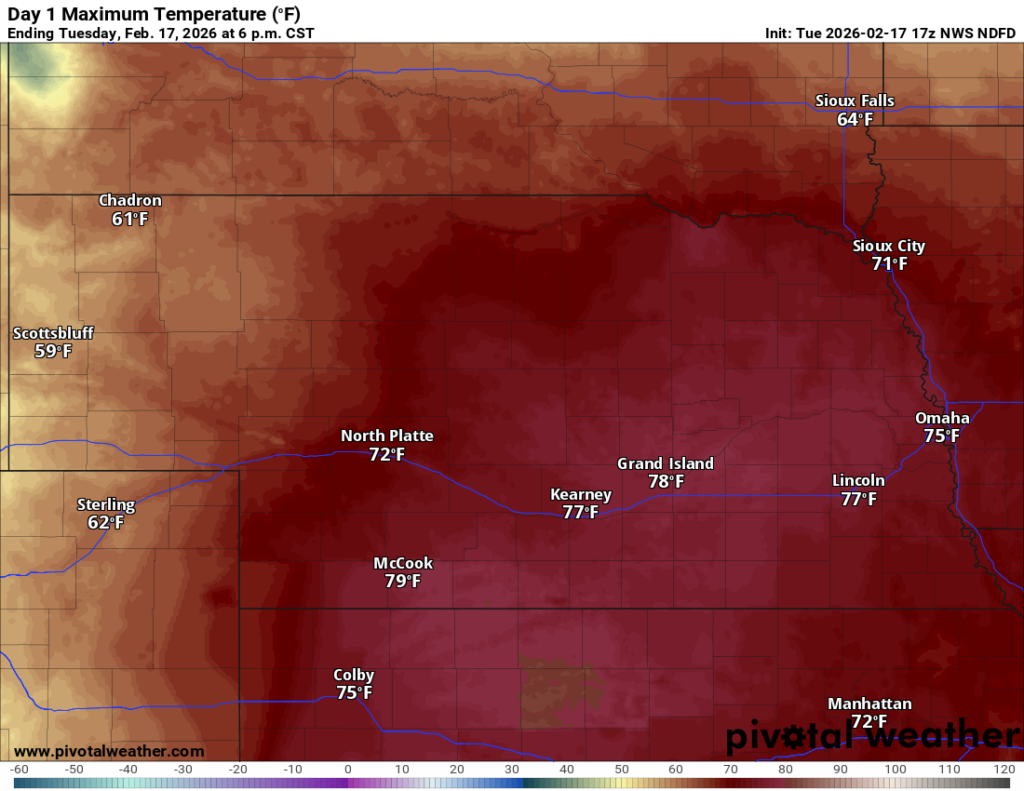

In terms of how quickly this sort of came about… There had been hints about this system for awhile now, but it really wasn’t until the last 36 hours that it really started to lock in. You can see the forecast precip from the European model for the last several runs and how it took some time to show up and lock in — and even then there were some issues with consistency!

You can see from an animation like this how little it takes to take a storm from being a nothingburger to being an extremely high impact. Most of this has to do with geography, right? The storm forecast may have only shifted by tens of or a couple hundred miles over a week, but it just so happens that several million people live near the coast. Snowstorm forecasting in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic is not for the weak!

Anyway, our hope to all in the storm to be safe.