In brief: We take a look at the northeast Gulf disturbance that may try to develop this weekend, but regardless it will be a rainmaker for the Gulf Coast and Florida. We also look at the latest on the hurricane satellite and proposed NOAA budget debacles.

Welcome to July. We’ve all survived month 1 of hurricane season. Only 5 months to go.

Northeast Gulf disturbance risk

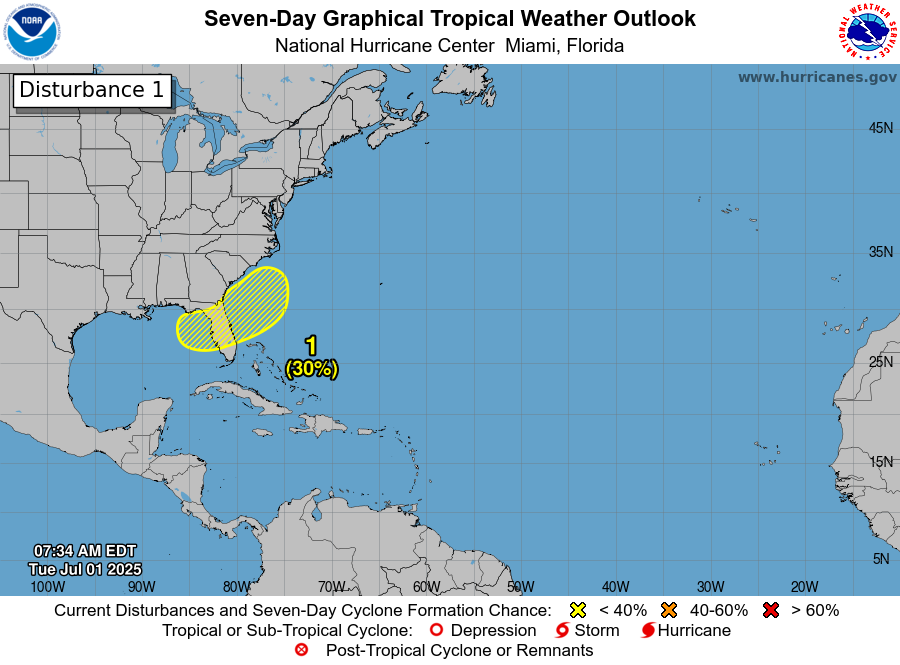

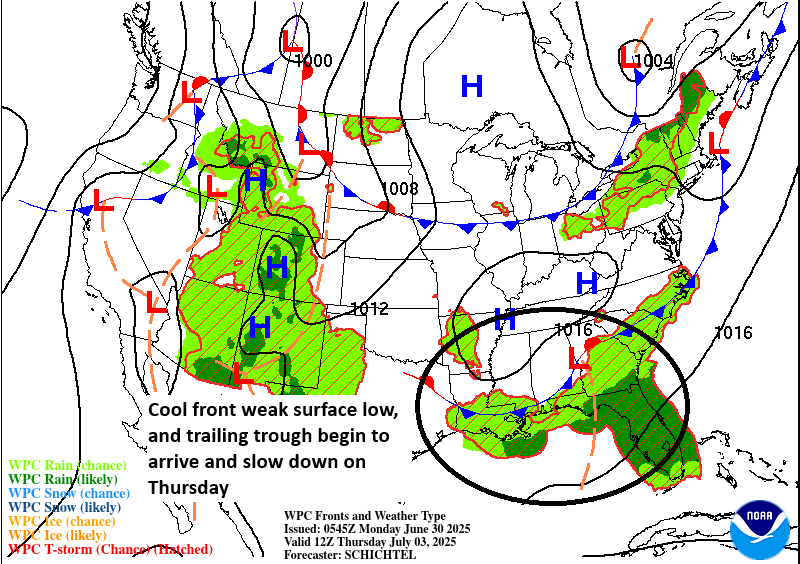

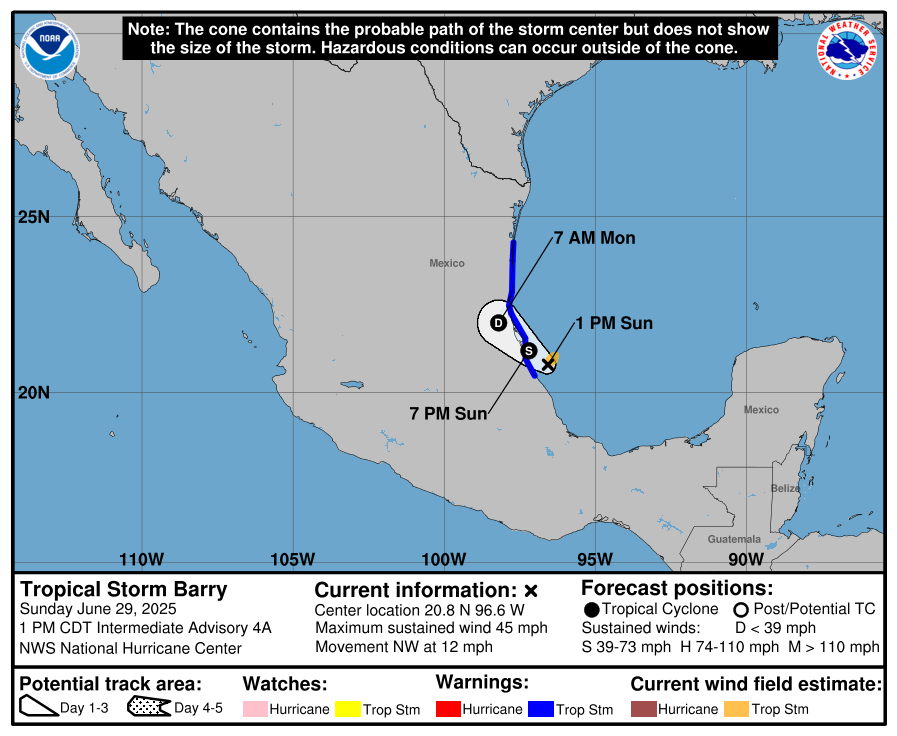

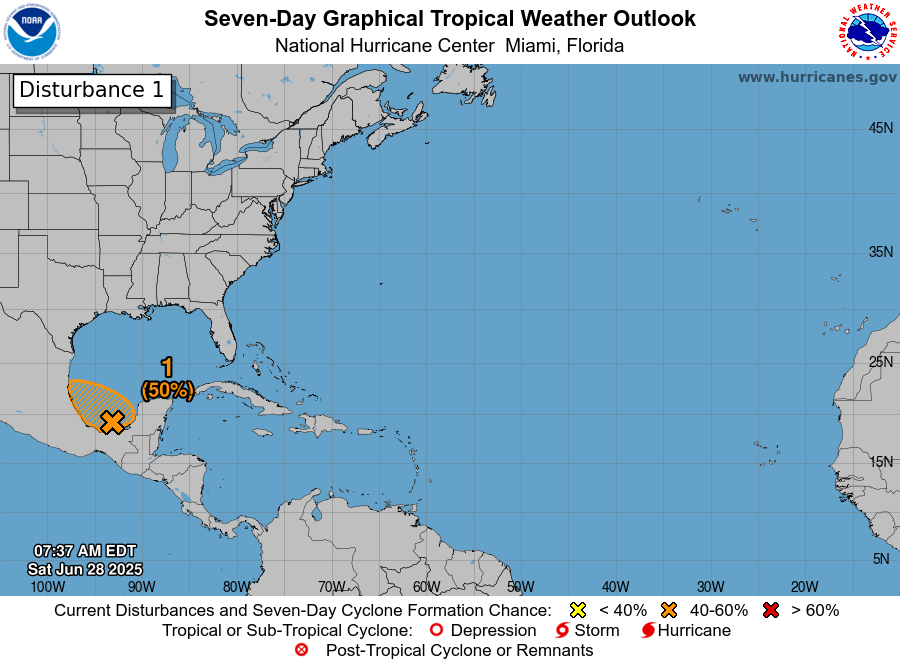

The NHC has nudged up the odds of development to 30 percent today for the projected disturbance along a dying cold front in the northeast Gulf or southwest Atlantic.

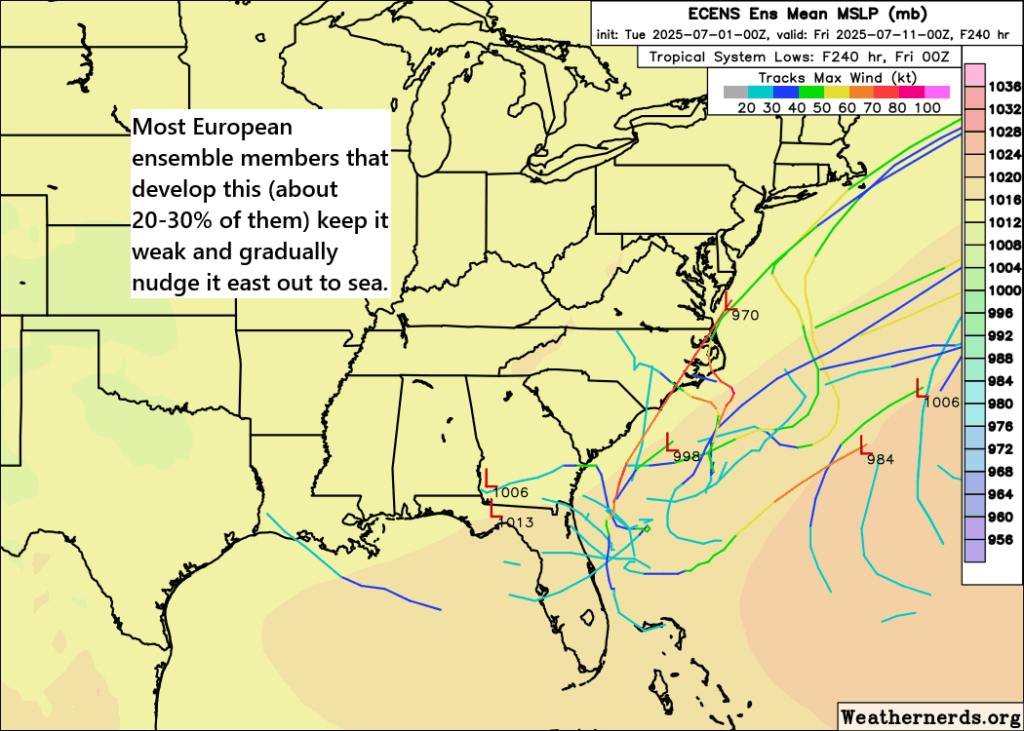

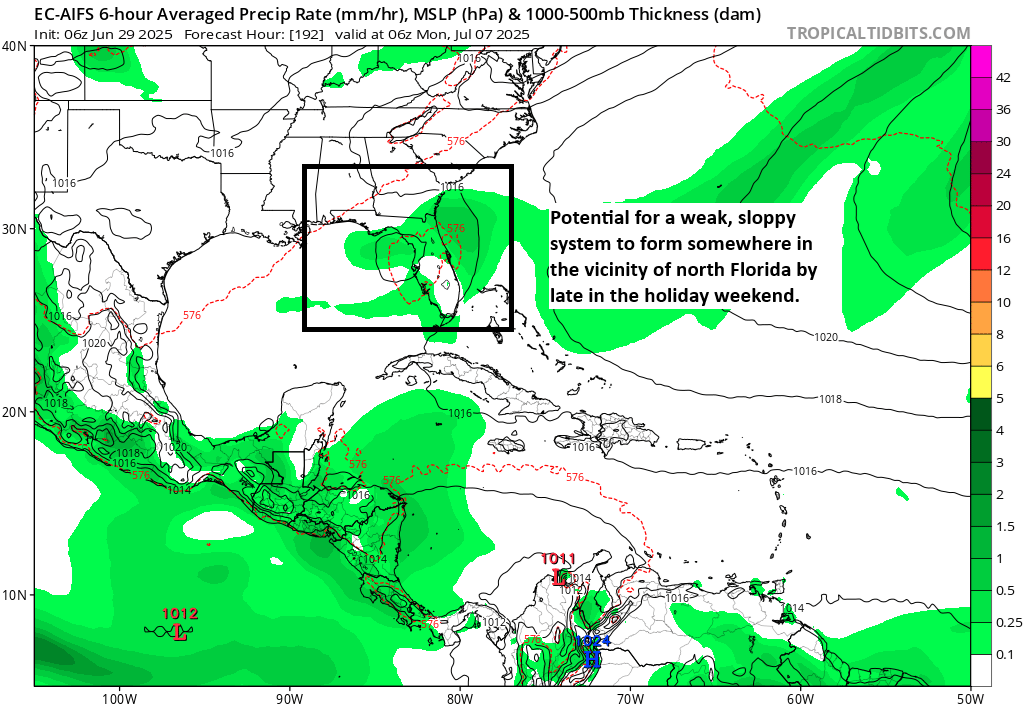

The only meaningful change I’ve seen in guidance today has been to basically shift the risk a little more to the Atlantic side. In fact, it almost looks like we get two disturbances out this mess next week, one that comes west or southwest and another that drifts around Florida and into the Atlantic. In fact, if you watch the European operational model loop below, showing “spin” (or vorticity) at about 10,000 feet above our heads, you can see how a chunk of the disturbance actually breaks off and drifts west, while the primary disturbance slides (or meanders) to the east.

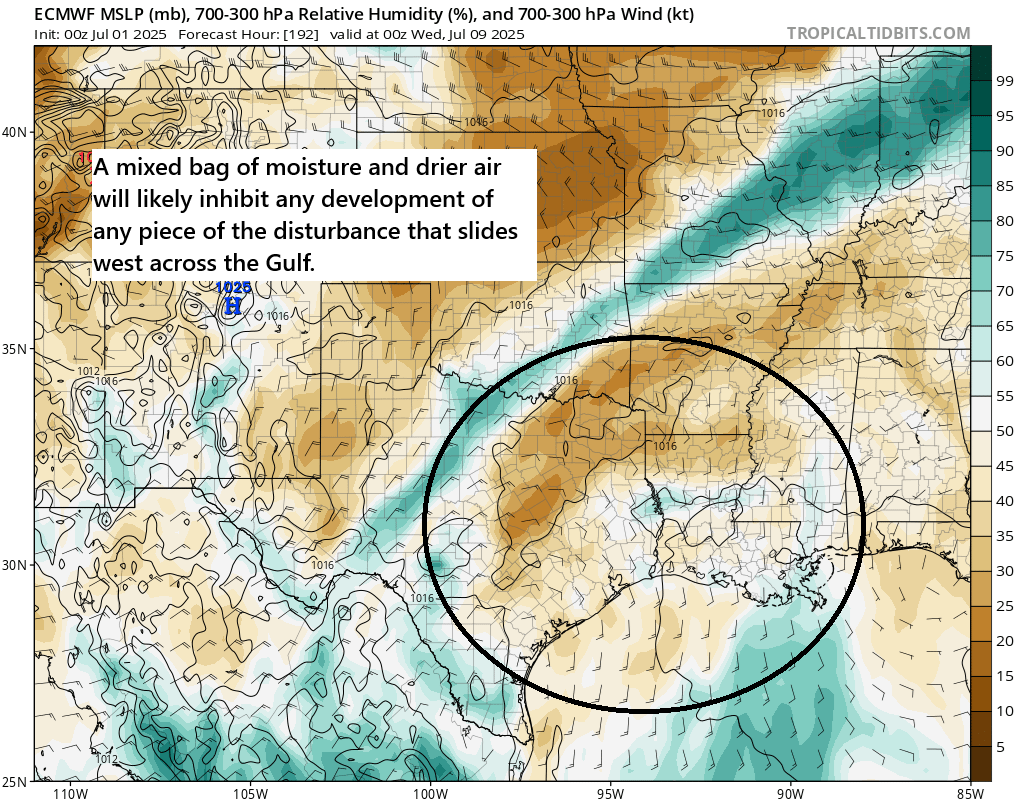

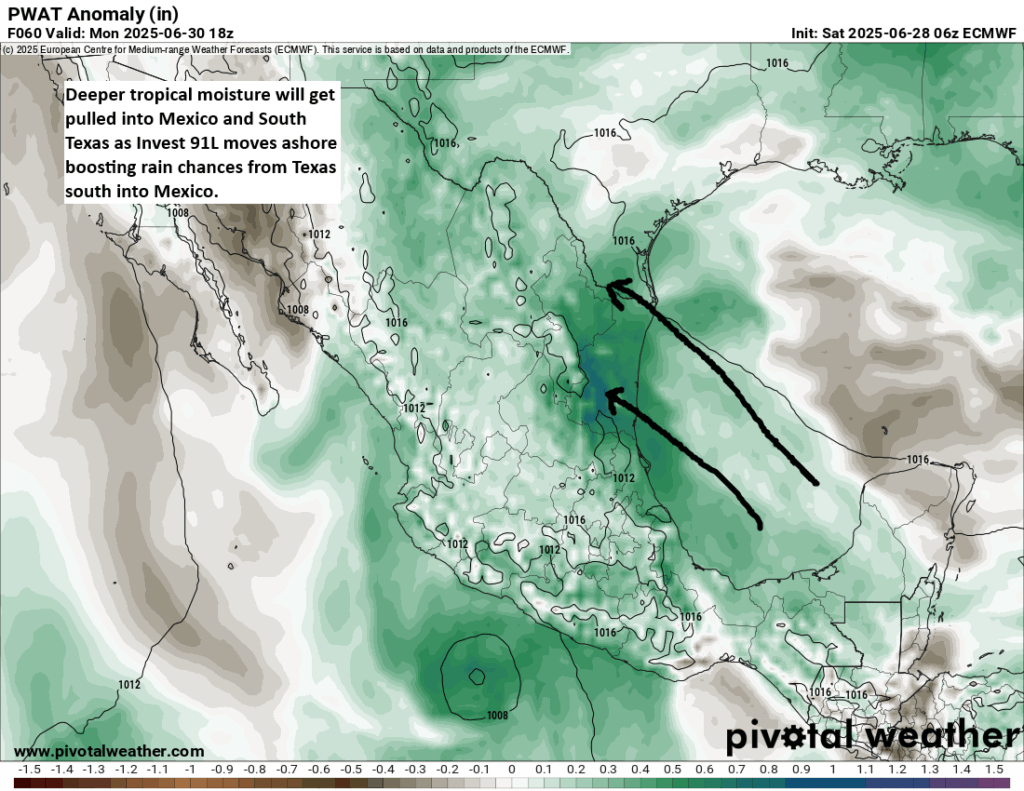

The westward, weaker one will probably struggle because a.) it’s too close to land and b.) the air in the western Gulf isn’t exactly expected to be loaded with moisture as high pressure sits over the western two-thirds of Texas.

The easternmost disturbance is probably what I’d focus on for development chances, but even with that one, they don’t exactly look super bothersome. Most of the European ensemble members don’t develop this in any appreciable fashion. The ICON and European AIFS AI model, last year’s big breakouts don’t do much with the Atlantic system.

Bottom line: 30 percent seems like a fine place to be right now. Any potential development probably has a low ceiling, with the highest odds of development shifting more into the Atlantic today. Still, because it’s the Gulf and it’s hurricane season, we’ll continue to monitor things.

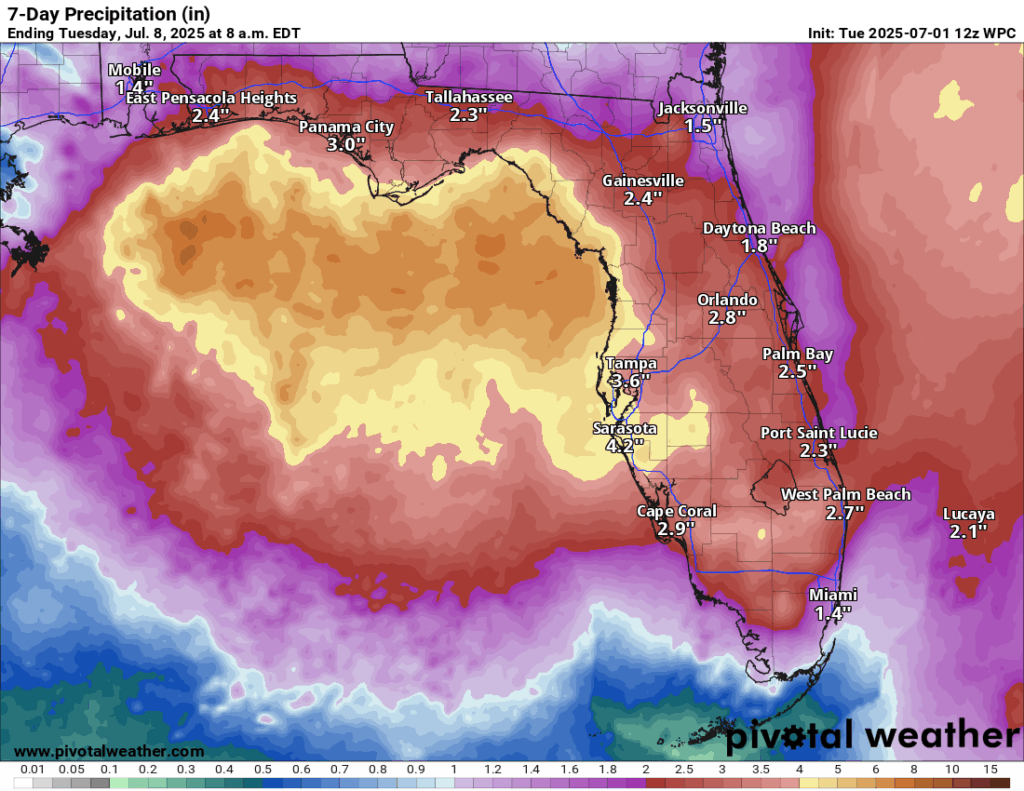

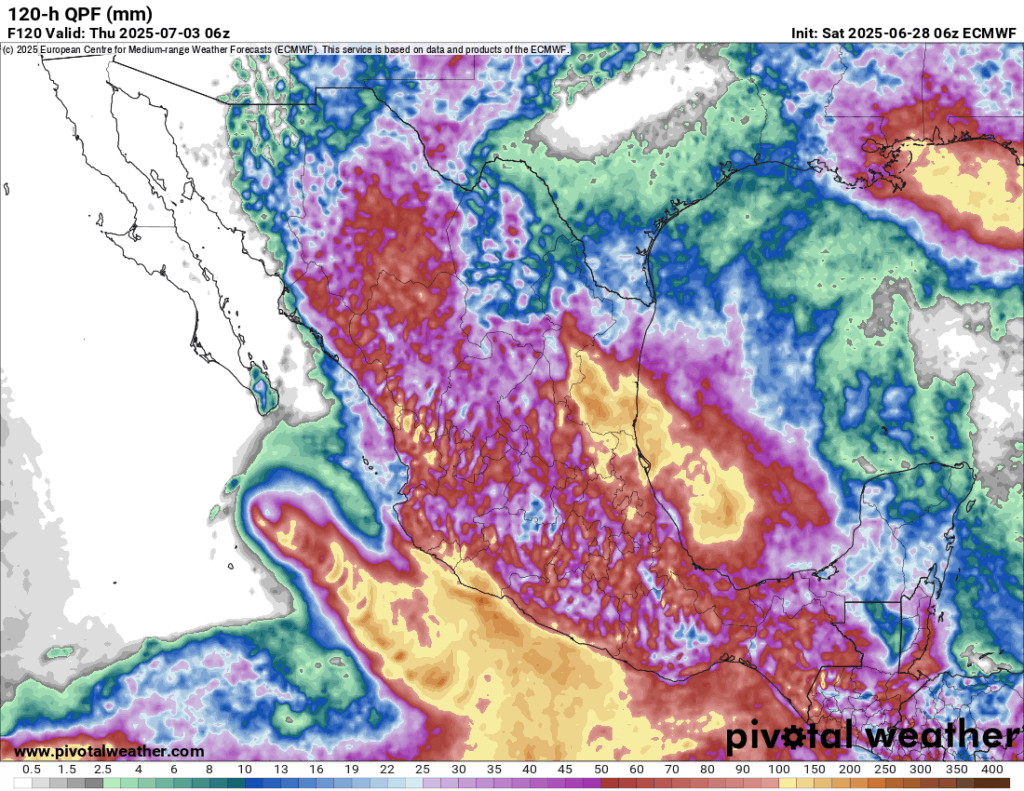

One thing is for sure: Heavy rain is likely in Florida. While the heaviest and most persistent rains will be confined to the Gulf Coast of Florida, where upwards of 4 to 7 inches is possible, the rest of the state will see a bit of a pickup in rain chances as well. Gradually, flooding could become part of the issues here as we head into next week.

Aside from this one, there are no other Atlantic tropical concerns.

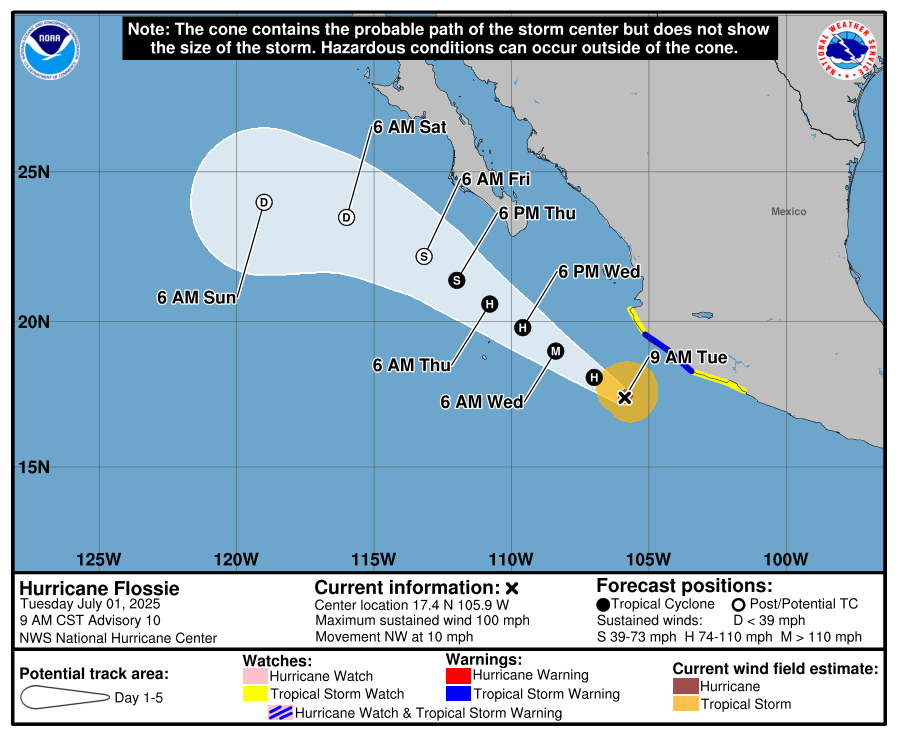

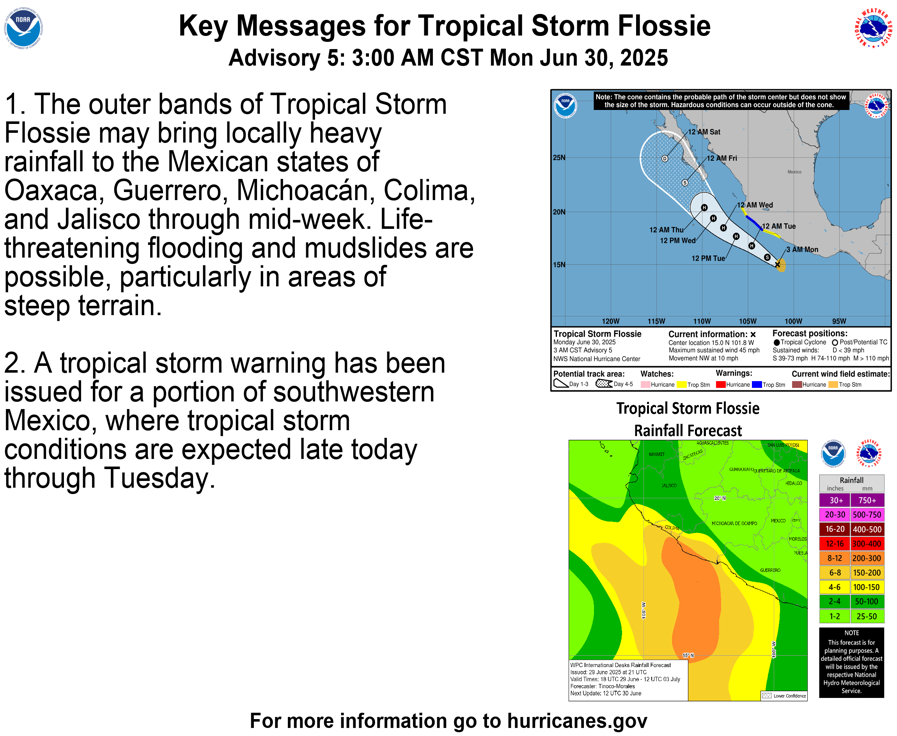

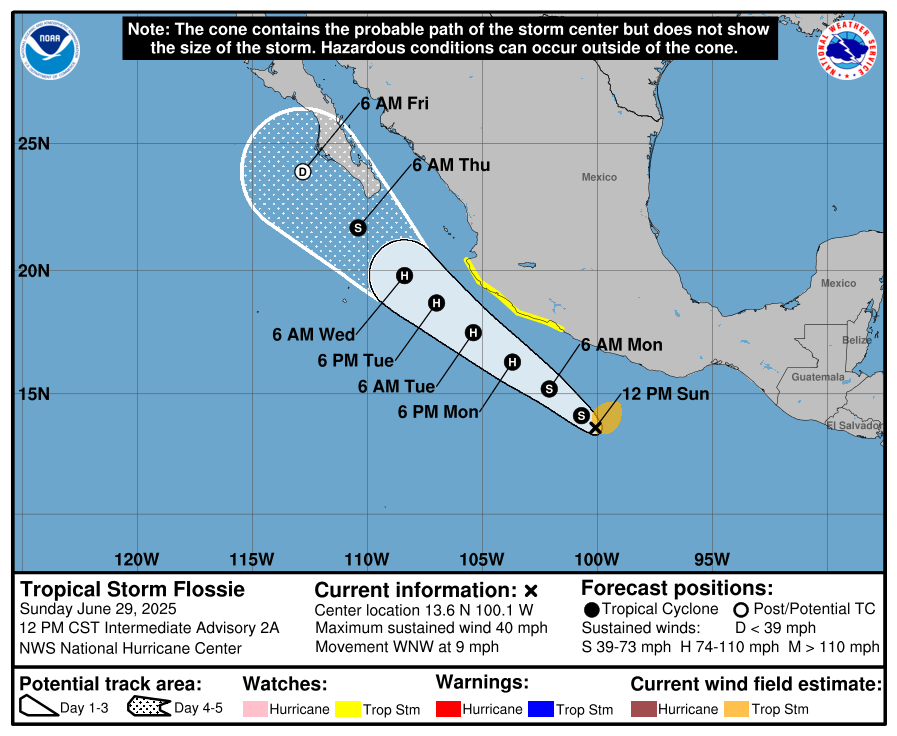

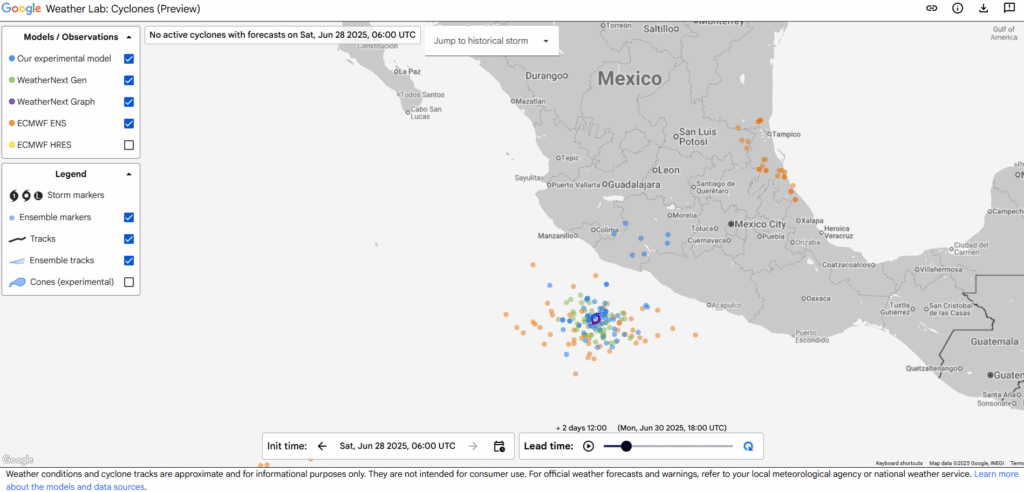

Pacific Hurricane Flossie

A quick note on Hurricane Flossie in the Pacific. Fringe impacts along the west coast of Mexico should be gradually winding down into tonight as Flossie pulls northwest and eventually away from the coast.

Flossie is now expected to become a major hurricane as it pulls away before falling apart well off the coast of Baja late this week.

Satellites and budgets

Semi-good news, and very, very bad news today. The good news is that the satellite sounder we’ve been discussing since last week, a key cog in the hurricane observations and forecasting process was granted a whole additional month of service by the DoD, letting it go until August 1st. Hopefully we can get this extended to November 1st, but we’ll see.

Secondly, and in much, much worse news, the official NOAA budget request was sent over to Congress yesterday. Because I don’t want to be accused of being biased, all I will say here are two or three things.

First, all you need to read about this topic has already been written. Alan Gerard tackled it last night in eloquent, nuanced fashion. Michael Lowry discussed the hurricane angle more specifically this morning.

Second, here’s the deal. American has been the undisputed global leader in weather research in recent decades because of the investments we have made in research and development. We have a major research base that produces tools that forecasters (like me!) can use when rubber meets the road. These tools save lives and protect property and make us an otherwise safer, more informed nation. We don’t often get surprised by weather like we did 50 to 100 years ago or more. This budget being sent to Congress is a disrespectful slap in the face to all those efforts and will allow America to abdicate the role of dominance in this space to another nation (more than likely China). It makes us less safe, less informed, and it will set meteorological and climate (not just climate change) research back years or more. The only logical reason one would propose this budget is if they had an agenda that wants to end American dominance in this space or wants to willfully make Americans less safe and informed. Full stop.

If you’re a deficit hawk and want to cut spending, this bill does absolutely nothing to tangibly change the federal deficit at a cost far greater than any savings could ever be. It is almost shockingly non-sensical. While this is strong language and this may sound like a politically biased or motivated take, it isn’t. For the life of me, I cannot understand who thought this was a good plan to propose and why they’d propose it at all. Nothing about it is America first, makes America great, or helps Americans rich or poor. It is a universally disastrous proposal, and we can only hope that Congress course corrects this quickly.