Headlines

- Hurricane Beryl was “only a category one” storm, so how did it cause so many issues?

- Today’s post tries to bust the myth of “it was only a category one.”

Hurricane Katrina’s first rodeo

Back in August of 2005, South Florida was struck by a hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph. The storm made landfall near the border of Miami-Dade and Broward Counties. It killed 14 and caused the 2024 equivalent of $1 billion in damage. It was Hurricane Katrina, and while the storm is obviously remembered for the horror it inflicted on the Gulf Coast, Katrina’s first act was to catch South Florida a bit off-guard. Katrina dumped 10 to 20 inches of rain and knocked out power to about 1.5 million Floridians.

Katrina intensified from about a 50 mph tropical storm to an 80 mph hurricane in the 24 hours leading up to landfall in South Florida. By the time it re-emerged into the Gulf of Mexico, it had only lost a bit of intensity. You can view a great radar loop from Brian McNoldy’s archive here, and you can see how the storm really got its act together right at landfall.

There have been numerous category one hurricanes that have hit land over the years. Yes, most are generally well-behaved. Most cause some damage but not exceptionally long-term disruption. Katrina bucked this trend somewhat, and early this month, Beryl did the same for Houston.

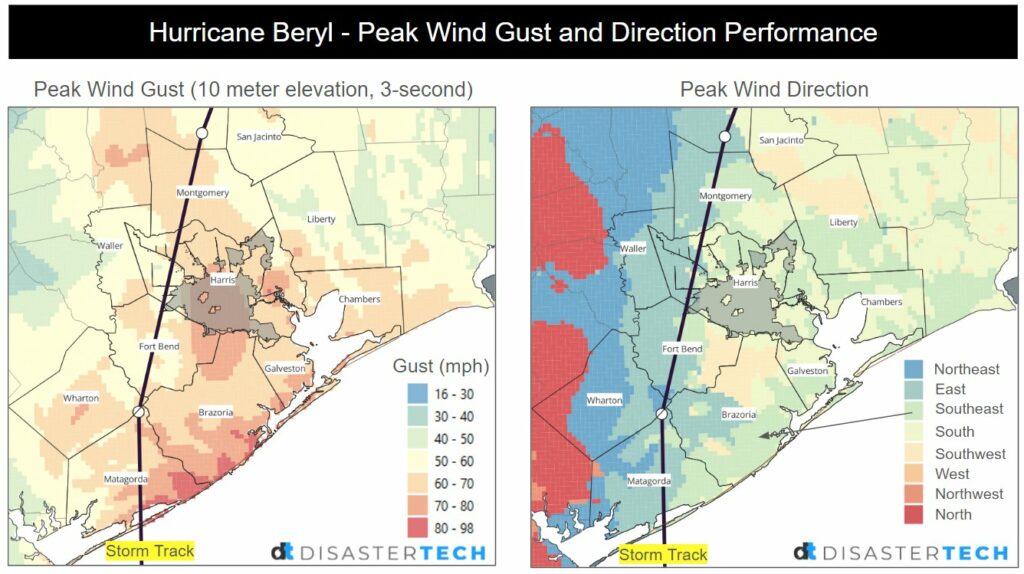

During Katrina, winds gusted to 97 mph in Homestead, 94 mph in Virginia Key, 82 mph in Fort Lauderdale, and 78 mph in Miami. During Beryl, winds gusted to 97 mph just near Freeport, 85 mph in Angleton, 78 mph in Galveston, 84 mph at Hobby Airport, 83 mph at Bush Airport, and 89 mph at the University of Houston. In some ways, Katrina and Beryl make for a nice case study of like-minded category ones. And they also blow away the myth of “it’s only a category one.”

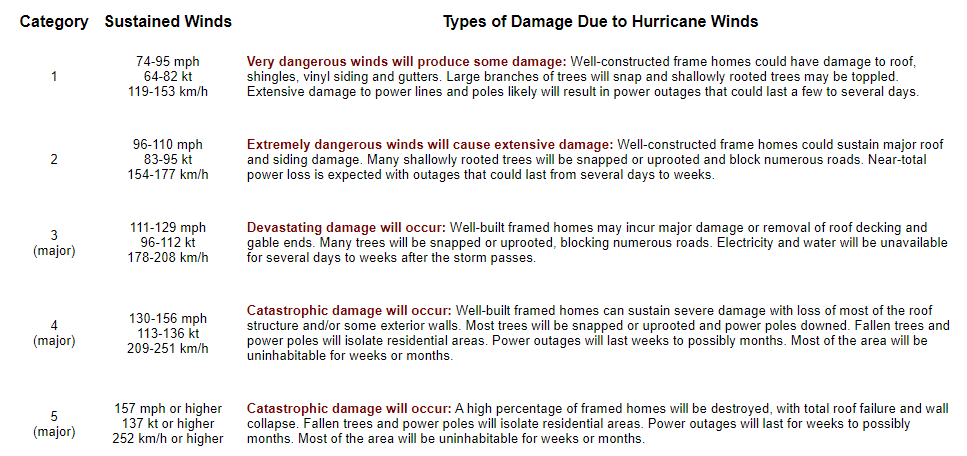

The usefulness of the Saffir-Simpson Scale

For hurricanes, we’ve long relied on the Saffir-Simpson scale to guide us in terms of the definitive categorization of intensity.

It’s a great tool for bucketing hurricanes in terms of their strength. Category 5 storms like first ballot hall of famers Andrew, Camille, and Michael generally fit the idea of the scale nicely. It tends to work even better when you consider “major” hurricanes, those that are category 3 and higher. The vast majority of memorable, devastating storms will fall into those buckets.

The uselessness of the Saffir-Simpson Scale

While the scale has true scientific value, many disparate voices within the meteorology and social science communities and beyond have long argued that the Saffir-Simpson Scale falls short in conveying the true threat to the public from a given hurricane. Think about Hurricane Harvey. It was a category 4 hurricane with massive damage on the Middle Texas Coast. By the time it arrived in Houston, it was a tropical storm, but it produced arguably the worst flooding event in Texas history. Hurricane Agnes in 1972 was only a category 1 storm but ended up being the costliest hurricane in American history at the time. The Saffir-Simpson scale, for all its usefulness is based on one variable and one variable only: Maximum sustained wind. If you have a 25 mile radius of hurricane winds that hit 155 mph winds, you have a category 4 hurricane. Whereas a storm like Hurricane Sandy before it was classified as extratropical was “only” a category 1 storm with 85 to 90 mph winds but had a wind field that sent hurricane winds out 175 miles from the center. Which storm is capable of more damage? Or are they capable of equal damage?

Thankfully, most meteorologists recognize this and tend to focus on the impacts more than the category of the storm.

Beryl came in like a wrecking ball

This brings us to Beryl. Right off the top here, let me explain some Matt philosophy for you. Prior to Beryl, Matt believed that things would generally be fine in Houston during category 1 or 2 hurricanes because once they arrived in the city, we’d have gusty winds, some power outages, and scattered damage. But overall, we’d get back up on our feet rather quickly. I even basically said as much literally a few hours before Beryl’s eyewall moved into Houston.

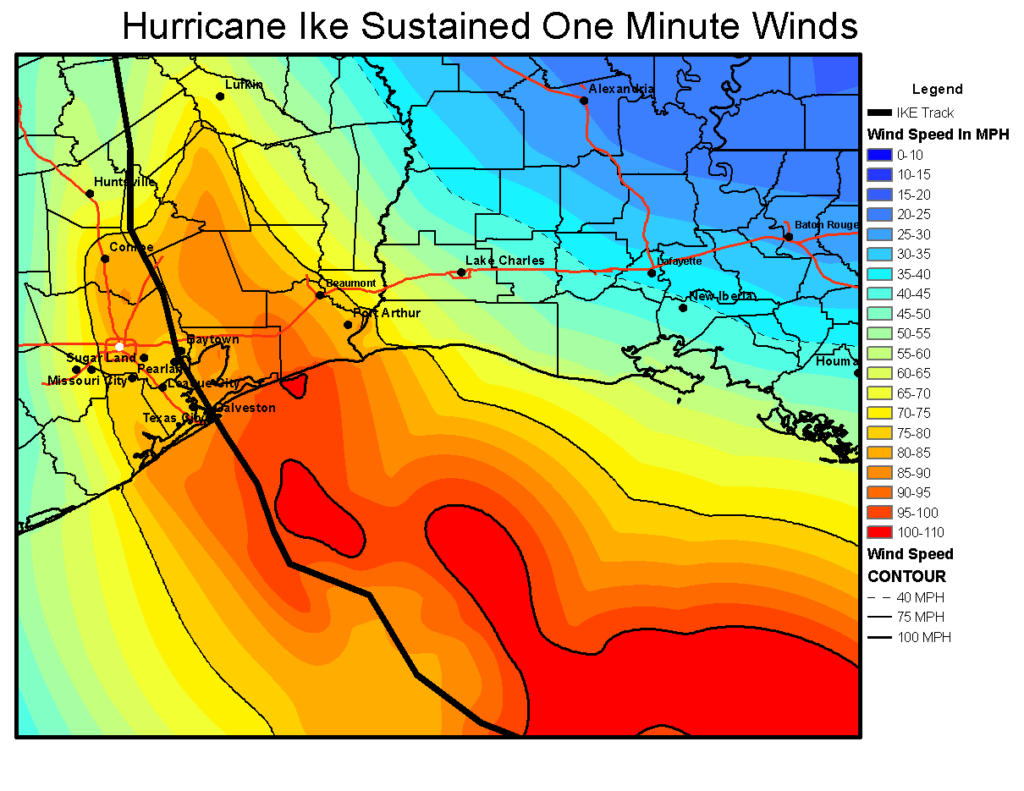

Yes, we did see the forecast 40 to 80 mph wind gusts, but it was more like 60 to 90 mph over the entire metro area. I believed we’d fare well, given that Hurricane Ike, a much larger and somewhat stronger storm in 2008 knocked out power to 2 million customers for up to 2 weeks, even though most of the Houston metro experienced the western (weaker) side. I figured, Beryl, smaller, weaker, but the dirty side…we’ll have outages and some damage, but we’ll manage.

Sustained winds were higher during Ike, but wind gusts in Beryl came up to basically match some of those sustained winds.

Here we are comparing a category 1 relatively compact hurricane to a category 2 unwieldy, large hurricane.

Why did Beryl match Ike’s scope of power outages despite being a weaker storm? First, the track put Houston on the stronger side, so most of the metro area saw the eyewall of Beryl and the strongest winds. Second, and this is where our expectations probably failed us most: Ike was weakening on approach to Texas. Beryl was entering rapid intensification. Beryl was only slightly weaker when it arrived in Houston as it was on the coast. Ike was about 110 mph at landfall and 95 mph once in Houston. Beryl was 80 mph at landfall and 75 mph once in Houston.

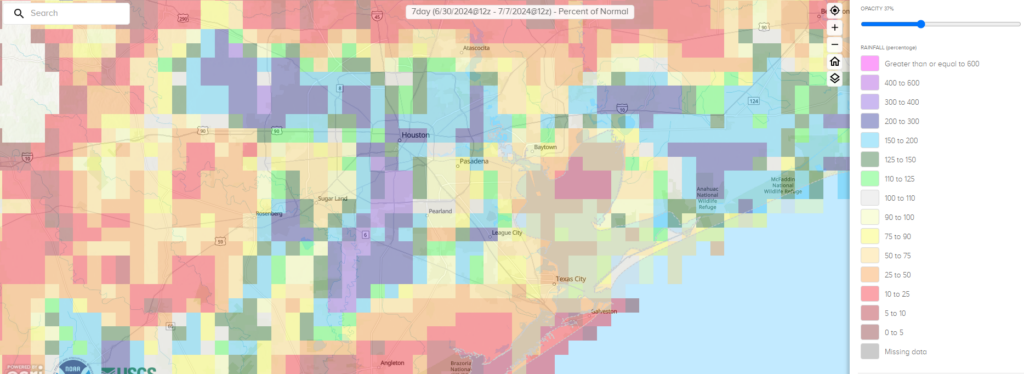

It barely weakened. Why? I think there are two reasons. First, Beryl while undergoing rapid intensification up to landfall took some time to unwind. There is absolutely a difference between a hurricane ramping up at landfall and one that is already decelerating. My new philosophy on this will be to add a category of wind impacts to a storm that is intensifying up to landfall. Second, Beryl was traveling over an area that had seen about 200 to 400 percent of normal rainfall over the prior week.

For Houston and points south, basically right on Beryl’s track, we had very soggy ground. This likely contributed both to Beryl maintaining intensity and the wind damage it caused. Trees fall more easily on saturated ground. Could there be an element of brown ocean effect at play here, where hurricanes can maintain intensity over land? Maybe, but that’s a longer-term research project.

There’s certainly an argument to be made about whether or not the power infrastructure in the Houston area is underprepared for the true threat this region faces. After Katrina hit Miami in 2005, 90 percent of customers had power back within three days. Three days after Beryl, about 58 percent of customers were back online in Houston. I don’t want to use this post to assign blame or recommend what should be done, but given that a category one or stronger storm can hit Texas every other year or so on average, this is probably an area that should be a wake up call. Texas should be attempting to match Florida, which has done great work in the hurricane resiliency space, between power restoration and building codes, despite some occasional hurdles.

Most importantly, I want this post to convey that there is honestly no such thing as “only a category one” hurricane or “only a tropical storm.” While classifying storms is good from a scientific standpoint after the fact, it’s not always great science communication in real-time. This was certainly a wake up call for me, and I hope it will be for others that the only thing that matters in each unique storm is what the impacts will be. And hopefully we can convey them in an understandable way to folks here in Texas and elsewhere as our site grows across the Gulf and Atlantic.

And we’ve added 1.5 million people since Ike I believe. And, we don’t trim trees like we used to. And, Centerpoint is a public company.

We could order all to buy $500 1 week house battery, we now have good batteries unlike Ike. Really a cellphone and internet is what most care about, with little fan a nice plus.. we just need a little power that 1 week to be half comfortable….

Thank you so much for your thoughtful expertise and devotion to understanding the illusive nature of our weather here along the gulf coast! Your perspective provides deeper analysis that offers peace of mind, acceptance of weather’s ever-changing dynamics and patterns. Thank you!

Great analysis and information. We all know the problem Houston has. Hopefully y’all fix it soon.

Great summary of what’s really happening with these storms and our dependency and foolish dependency on destructive power based on assigned category.

Seems that each storm needs to be analyzed on its particular attributes and potential for delivering on all its fronts.

Excellent info in your posts. As a long-term Florida resident I always appreciate your insight on the possibilities.

I still remember “tracking” hurricanes with my dad in the 1960’s using a map and plotting the reported latitude and longitude. That told us where it was. No one could ever tell us accurately what would happen next

I think I remember that Ike was a category one Hurricane as well. But if I remember correctly it covered the entire Gulf of Mexico. So it was gigantic and I think size matters with tropical storms. Beryl was a one but smaller and moved more quickly. And I think I remember a tropical storm, not even hurricane strength that did a lot of damage.

I remember thinking, well, Beryl isn’t large in area, so we’ll be fine. Oops.

Good write up on the factors that lead to the large amount of damage Hurricane Beryl was able to do. I think the brown ocean effect and rapid intensification up to landfall are reasonable to point to the underestimation of the impacts.

I think it is also reasonable to point blame where it belongs. The state government and Center Point energy. Even with a perfect forecast and ample time to prepare, Houston would have still seen nearly the same damage regionally. The shortcomings in our system are generally not the onus of the individuals. As strong as Beryl was even the gust barely scratched into Cat2 ratings. The nature of the industry (petro-chemical) in the Houston area should motivate us to have better infrastructure in place. When (not if) this region has a Cat3 or stronger storm make landfall or multiple Beryl type storms in succession, the viability of our region depends on it.

Great article. The state government is definitely to blame because of their fear of regulations! This has gotten us in trouble on many occasions. On the whole I feel, Center Point did an exceptional job given the circumstances! It was the same with the “Deadly Freeze”! When there is no emphasis in infrastructure on preventive maintenance, the people suffer! Those able to afford whole house generators versus the rest who cannot is no acceptable solution. Then for Abbott to breeze back into town finger pointing, was the height of hypocrisy. Government should always be for the good of the people…all the people! God bless those Center Point linesmen and those from out of state or county! We owe them a huge debt of gratitude!

It also is interesting that the ICON model (not one usually referenced/relied on) was probably the best (even a week out) in terms of identifying that the storm was more likely to come into the upper Texas coast. Now if you could identify some model that would reliably indicate what week Centerpoint’s CEO will resign or get fired that would be useful as well

Ike was a Cat 2. Period. It was a Cat 5 earlier in that week before it entered the GoM. It was huge, about the size of the entire Gulf, and we didn’t get the worst of the weather because it tracked right over the Bay and Downtown. Had it landed where Beryl did – we would have had the catastrophic surge flooding that the Ike Dike is being constructed to prevent. A storm stronger than Beryl with similar track will probably shut down Houston for 2-4 weeks, and places around here even longer. Galveston took a full year to recover from Ike.

I so appreciate you and all your expertise and guidance. The information you supplied during Beryl and previously is very valuable to us. Thank you for your efforts.

Fairly recently (a year?) Tachus laid Fibre Optic Internet cable in my area (Kingwood), too late for us now but is it possible when laying any other type of cables to just go ahead and run power along side and therefore significantly reducing damage in the next storm?

When I see the estmates of how much it woul cost run put all the power lines underground I guess not but even if small sections could be done piecemeal everyone would benefit after the storm when some neighbor hoods didn;t need any help.

Appreciate all your work and love my Generac whole house generator, sure it was expensive but 8 1/2 days w/ out power would have been gruesome.

I’ve been worried about what we’re missing since Katrina. When I called my mom from Memphis to say “this storm is going to be really bad! Look at it!” My mom in Pascagoula MS said “the winds are decreasing! It’s only a Cat 1. Stop looking at the internet!” Everyone in our family lost their homes and all their life’s belongings. Thank you for addressing the myriad of factors. You have a tough but very important life’s work! Alyce

To discuss.. Hmm.. A Cat 1 to 3 won’t blow walls off a modern house post 2000, so people survive. Roof may be gone but little death. Evac seems NOT needed, if have weeks of water and ice and food to ride out recovery. Do the math, 4 million shaken from Cat 3 and just say 40 die from tree limbs crushin room.

We will have 50+ heart attacks from evacuating 4m, do the math… We can’t tell everyone to evac from a Cat 3 cuz 80% don’t prepare and have supplies. That is where this approach is headed, telling all to flee from Cat 1 to 3, cuz of 80% wussies. So yes ONLY A CAT 1, 2, OR 3 IS message to us prepared that we can stay.

Back when I studied waves long ago, we considered fetch length, windspeed, and wind duration when calculating wave heights. In watching enormous differences in surge associated with different hurricane categories, I’m sure these factors play an equivalent role. For instance, a high speed, but short length and duration, will cause a lower surge. Vice-versa should hold. All three factors in the wind field are critical components affecting surge, which should be another rating or category beyond the Saffir-Simpson Scale. Hide from the wind, run from the surge!

Excellent article. Thanks for the insight and for keeping everyone informed throughout the storm.

So hurricane ike peak wind gusts were like 50% greater than beryl. That’s material.

The force applied follows the squared of velocity at that speed so that’s like 2.25x greater applied force.

Houston has a problem

I know you guys look at WeatherBell since you often use their maps. What do you think of their Power and Impact Scale as an alternative to the Saffir-Simpson Scale since it seems to take into account a number of the variables you talk about here. Including whether the storm is intensifying or not as it comes to the coast, the wind field extent for hurricane force winds, tropical storm force winds and gale force winds, etc. I believe they had Beryl as a 1.9 on that scale rather than just a 1. I’d appreciate your thoughts on their scale.

And thanks for all you and Eric do for all of us in the Houston area and nationwide.

A model of intelligence and humility: learning from experience!

Great article! First class!!

I’ve been very concerned with both (01) rapid intensification & (02) the trend where hurricanes are not slowing down upon close approach to land (don’t want to think about Katrina & Rita not downgrading from 5s to 3s).

I can’t see how brown ocean wasn’t a factor in Beryl – I guess we’ll see what is concluded.

Really appreciate you being there for us – it made a big difference in resilience for me, and I’m sure it did for many others, too ⚘

Our power went out around 4 or 5 am, before the peak wind. It was probably only gusting up to 40-50 mph. That is normal strong thunderstorm wind; not even reaching to “severe thunderstorm” levels. That should not cause power outages. I do not think Beryl was much stronger than anticipated; the problem lies with the infrastructure. Out country’s entire grid is getting old.

Our*

Great read! I always enjoy your thoughtful analysis of these things.

I had completely forgotten that Katrina trekked across Florida.

Love this commentary! Thanks for putting a new spin on how you will be looking at the storms in the future and admitting that forecasts can be misleading.