Headlines

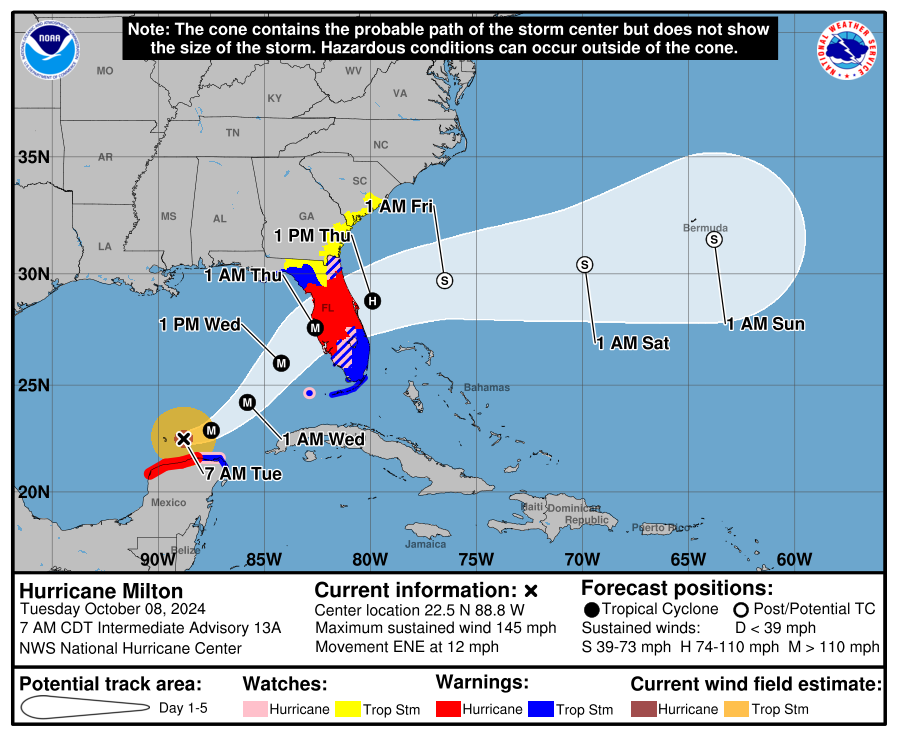

- Milton will fluctuate in intensity over the next 18 to 24 hours, perhaps once again becoming a category 5 storm for a time today.

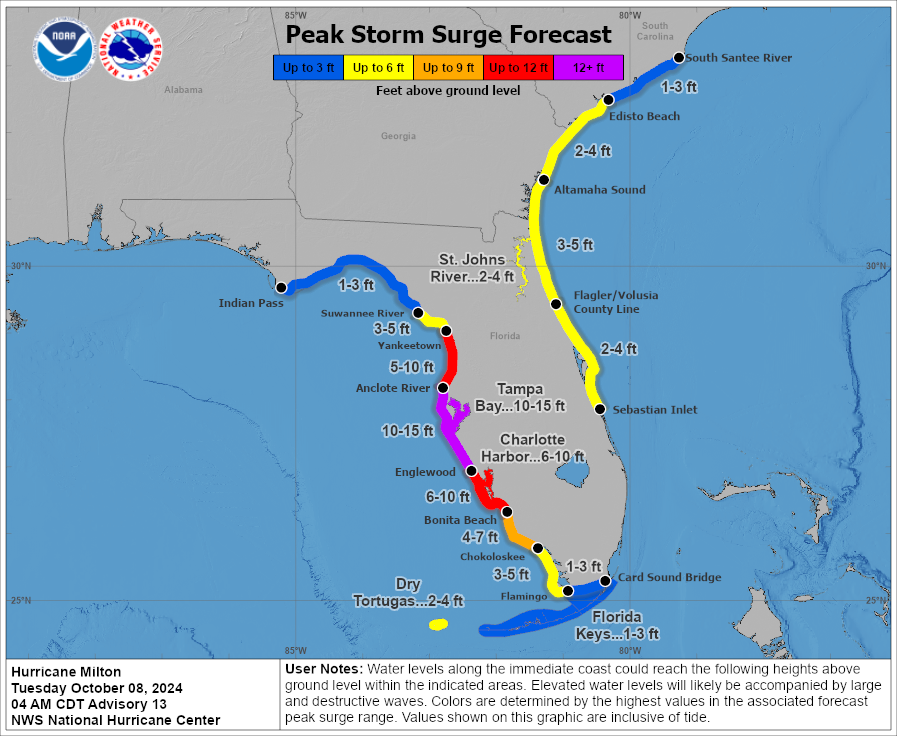

- Milton is growing in physical size, with an expanding wind field likely to help lock in significant storm surge when it makes landfall tomorrow night.

- For areas between Tampa Bay and Venice, this may be your version of Ian, with devastating storm surge and strong winds.

- For Tampa Bay, the track is still much too close for comfort with equal odds of it going just north of the bay (bad) or just south of the bay (bad, but less bad)

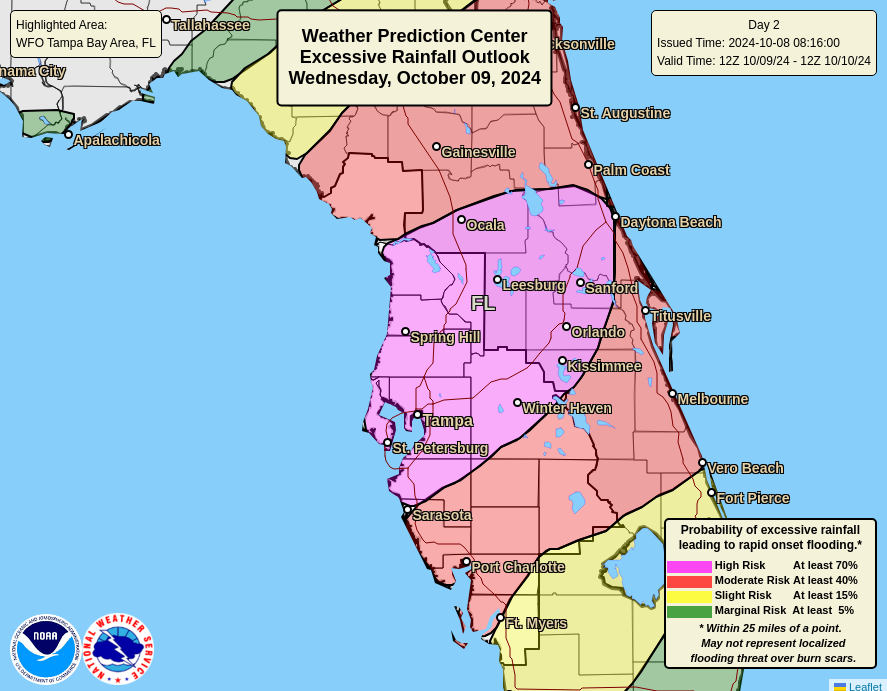

- Major freshwater flooding is a possibility due to 10 to 15 inches of rain that may fall near and north of the I-4 corridor, including Tampa, Orlando, and Ocala.

- Inland areas will see hurricane force winds and potential for substantial power outages.

Hurricane Milton bottomed out sometime yesterday evening with a sub-900 mb pressure, the type of storm we have only seen a handful of times historically. Tentatively it is the 5th strongest hurricane on record in the Atlantic, but we’ll see what happens from here and in the postseason analysis before that gets firmed up. But the takeaway: Milton is not just a powerful storm, it is a historic one.

Milton underwent an eyewall replacement cycle overnight. In a nutshell: That’s when a hurricane pauses its intensification, takes a breath, and typically grows a bit in size. Milton did just that, knocking its winds back to 145 mph, raising its pressure, but also expanding its tropical storm force wind field from 80 to 105 miles. Milton will continue to grow in physical size as it comes northeast today and tomorrow.

Milton will continue on a northeasterly path now. This will carry it into the west coast of Florida tomorrow night. Exactly where in Florida it crashes ashore is still to be determined. Modeling seems to be honing in on the area between Clearwater and Sarasota, but given the typical error 36 to 48 hours ahead of landfall, there’s still a wide berth here.

For Tampa Bay’s surge zones: This remains much, much too close of a call to risk riding out. Is there a chance this goes just south of Tampa? Yes. In that case, Milton will probably be damaging but not devastating specifically in Tampa Bay. But you’re talking literally a few wobbles or something like 5 miles of track shift, things that cannot be predicted making that difference. Assume the worst, hope for the best.

For areas south of Tampa Bay, things are locking in now unfortunately. This includes Sarasota, Venice, Longboat Key, and elsewhere. This may be your version of Hurricane Ian. The surge south of there into Charlotte Harbor, Punta Gorda, Cape Coral, and Fort Myers will be bad, at 6 to 10 feet, which is significantly lower than was seen in Ian but will be quite significant on its own. The bottom line: This is a terribly ugly storm surge forecast up the coast from where Ian hit in 2022. We cannot stress enough to try to evacuate if ordered, check on neighbors, family, and friends in the region, and hope that somehow or some way this is not as bad as it looks. I fear that is getting harder and harder to occur.

In terms of intensity, we may see Milton make a run back to a category 5 today. The next 18 to 24 hours will probably see some fluctuations in intensity, as is typically the case in hurricanes of this intensity. We’ll probably see the intensity wane some tomorrow, but because the storm will compensate by growing in size, it will be very, very, very bad. Milton should arrive on the Florida coast as a borderline cat 3 or 4 storm in terms of wind, with a surge that will punch above the weight class, closer to cat 4 or 5. Milton is almost certainly not going to “weaken” enough before landfall to matter in terms of impacts.

One thing that seems assured regardless of exact track? Rain. Flooding rainfall is likely near and north of the I-4 corridor tomorrow as Milton moves in. A high risk (level 4/4) has been posted for the area between Tampa and Daytona north to about Ocala. Moderate risks (which are also usually not good) surround this north to Jacksonville and Fernandina Beach and south between Fort Myers and Vero Beach. Total rainfall could be as much as 10 to 15 inches in the high risk area, enough to cause significant, damaging freshwater flooding.

For interior locations, I know this is a scary storm too. But while it will be damaging inland, the hope is that it’s manageable by sheltering in place. If you’re visiting, most hotels and resorts should be pros with this and able to keep you safe. If you live there, winds of 65 to 75 mph sustained and gusts in the 80s or 90s will be unpleasant but as long as you shelter in a sturdy home, you will be fine. Power loss will probably be the most significant problem there, with perhaps a few days without power. Just make sure you’re prepared for that. Run from the water, hide from the wind. East coast beachfront locations will deal with full fledged tropical storm conditions and some modest surge flooding as well.

As is always the case, isolated tornadoes are possible as Milton comes ashore tomorrow night.

Look for another update this evening after we take a look at the 5 PM ET NHC advisory.

This late season surge is really trying to make up for the quiet August, isn’t it?

Good information!

How long is that CAG supposed to be down there?

Ty

A quick Google search and hop on over to Wikipedia yields this bit of information: “It (Central American Gyre) primarily develops annually during the region’s rainy season between May and November, and most commonly occurs during late spring (May–June) and early fall (October–November).”

Thank you for all you do to keep people informed, thus safe, near and far. Even as far away as Nacodoches. iykyk

Why isn’t the Miami area considered to be at a higher risk? The models keep tracking further and further south, everywhere north and south of it is at higher risk, water temps are high, and it’s right on the dirty side for a counterclockwise band. What gives?

Miami is much further south than Milton’s expected track, and is on the Atlantic coast, not the Gulf side.

There are areas further south of Miami, also on the Gulf side that are at higher warning levels. That’s what doesn’t make sense.

Can you explain what areas you are comparing to, and which watch/warning levels?

All of the South Florida coast is under the same wind warning level (Tropic Storm Warning).

The areas under storm surge warning are on the Gulf side, as you say, because the surge is coming from the Gulf. Nowhere on the Atlantic coast is under storm surge warning.

(Correction: I meant that nowhere on the South Florida Atlantic coast is under a surge warning. There are areas further north that are.)

Miami is not under storm surge warning because of the wind direction. Wind will be blowing water away from Miami rather than toward it.

A couple of questions: Cat 5s don’t seem to last very long, is there some point where they just start to tear themselves up internally? In other words is a Cat 5 sustainable even with perfect developmental conditions? Second: what size does a storm have to be before Coriolis Effect influences its clockwise turn? I know it’s large and am curious how much of the shifting track to the south could be attributed to Coriolis given its Cat4/5 status?

The article mentions something called an Eyewall Replacement Cycle. This is, more or less, what you describe as the storm “tearing itself up internally”. The rainbands outside the eyewall become so strong that they become an eyewall of their own, leaving the storm with two concentric eyewalls. This isn’t sustainable – the new, “outer” eyewall robs strength from the old, “inner” eyewall, causing it to lose strength and eventually dissipate. The result is that the storm, now with a wider eye, spreads out and covers a larger area. But the new eyewall has slightly less wind speed, so the storm overall has less wind speed.

At the 48 hour pre landfall mark, when prediction is fairly firm based on past experience, Tampa Metro should assume it’s hitting them. Darn.

What about St. Pete? Are they protected being on the inside of the Bay?

The Gfs Cag modeling really seems to be heating up.

Is there somewhere online that we can go to monitor it closely? (I use TTs already)

I recall some discussion from Katrina days about the low pressure associated with the eye actually causes some water column rise that contributes to the storm surge. I haven’t heard any discussion on that in recent years. Is that now considered a minor contribution to hurricane surge?

What impacts can be expected in the Fort Lauderdale/Miami areas over the next few days?

Milton’s movement east slowed considerably from the initial forecast and is now expected to make landfall about 20 hours later than the early estimate. Is that a partial explanation for the rapid intensification, or is it possibly the other way around, and the intensification caused it to slow?