In brief: There’s some pretty high fire risk on the Plains today, as powerful winds impact the region, along with some mountain snow and snow near the Canadian border. Today, we also take a detailed look at how negotiations on a revised Colorado River compact failed spectacularly and what may come next.

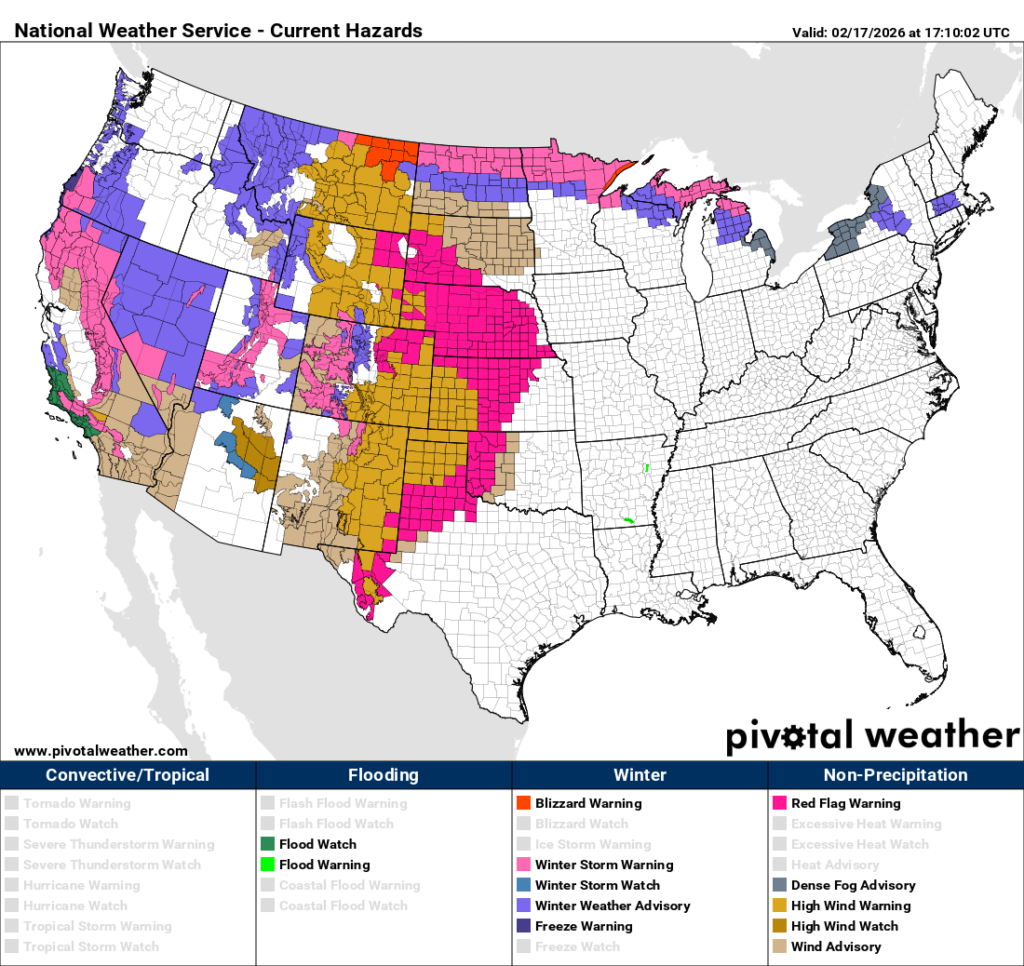

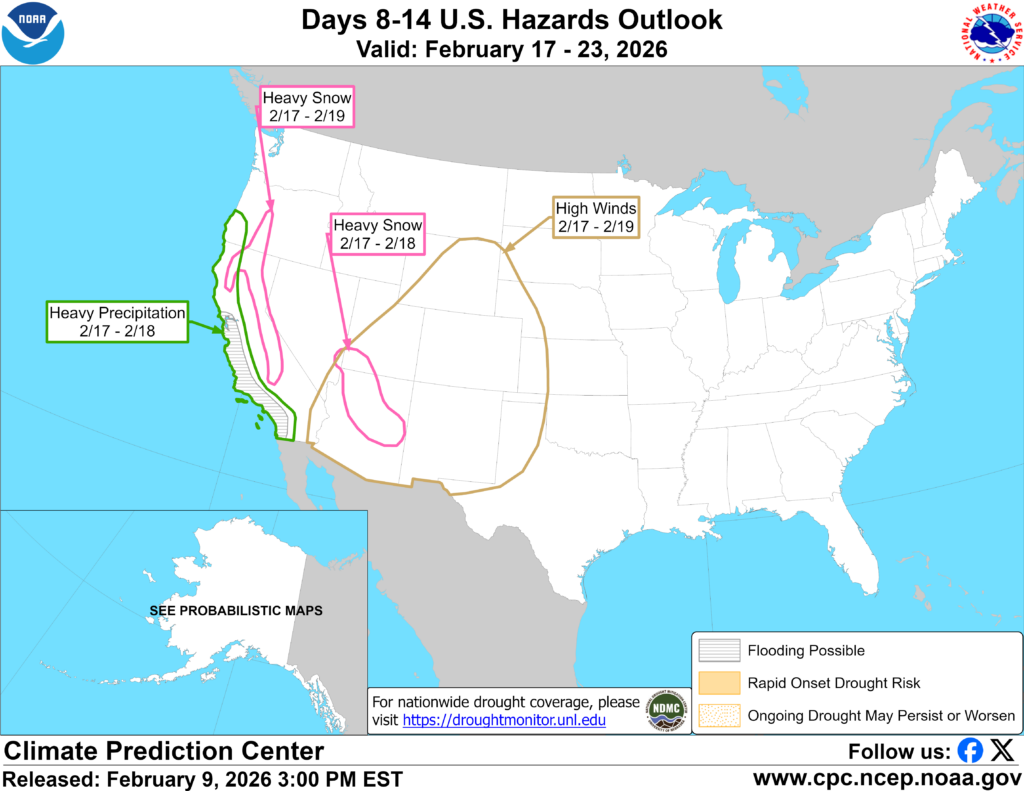

A rollicking storm is going to push across the Western U.S. today, leading to a wide swath of gusty winds and high fire danger on parts of the Plains and in the West. High wind warnings and red flag warnings stretch from the Big Bend of Texas to the Bighorn Mountains in Montana.

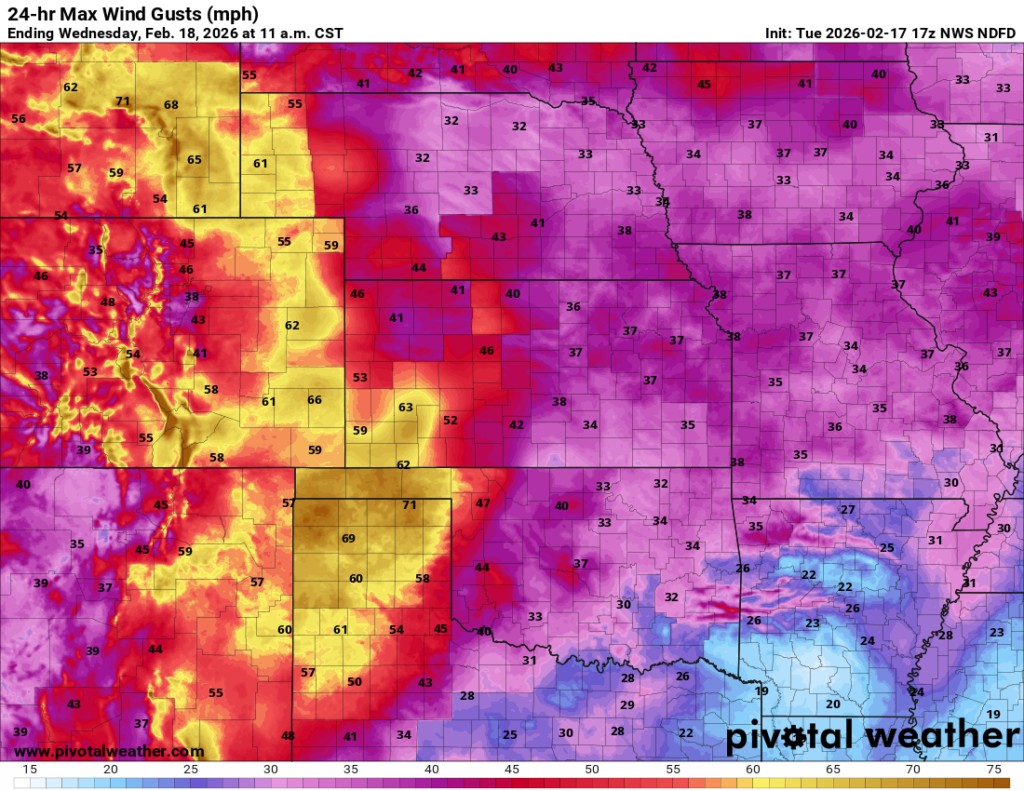

Between precipitation in California and the interior West, the wind, and the fire risk, this one has it all. The wind gusts today are expected to be…..

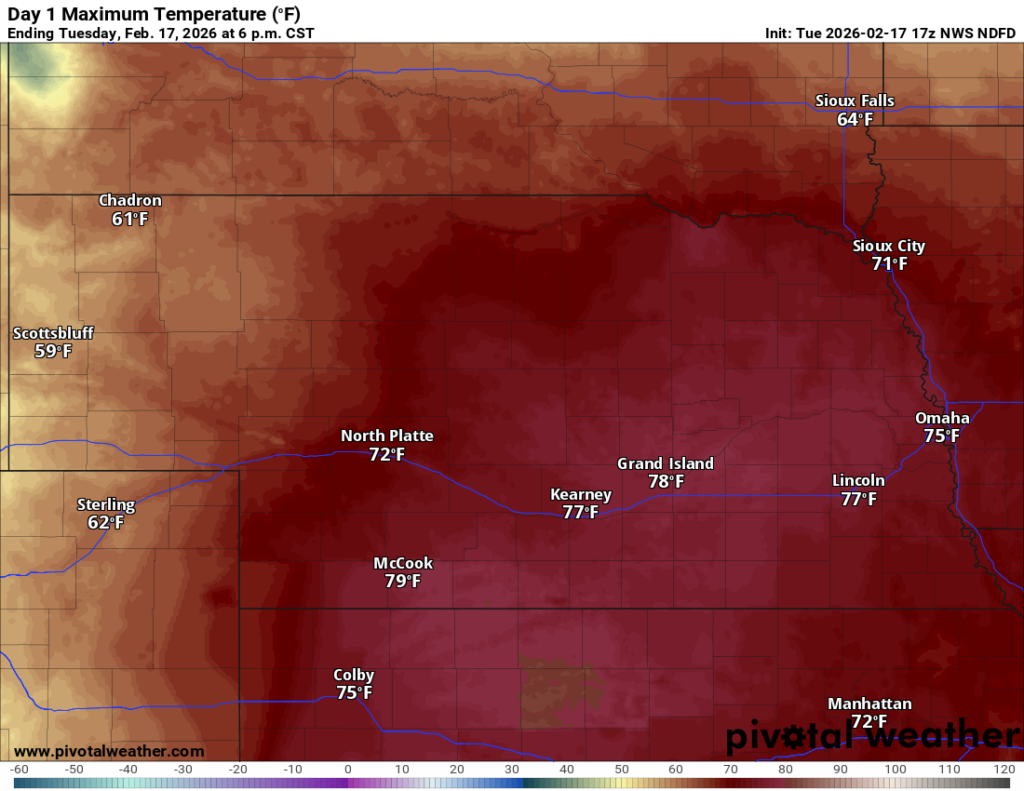

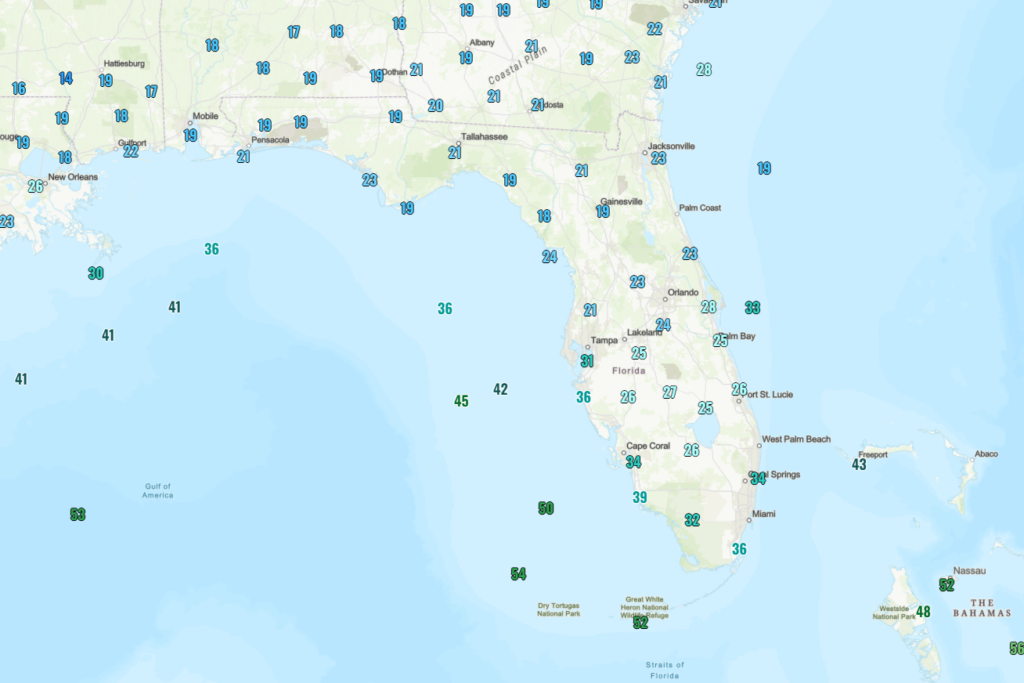

In addition to the winds, we are going to see some potential record warmth in the Central U.S., with much of Nebraska likely to push records well into the 70s. Even Abilene, Texas is expected to hit the mid-80s today, tying a daily record from the late 1800s.

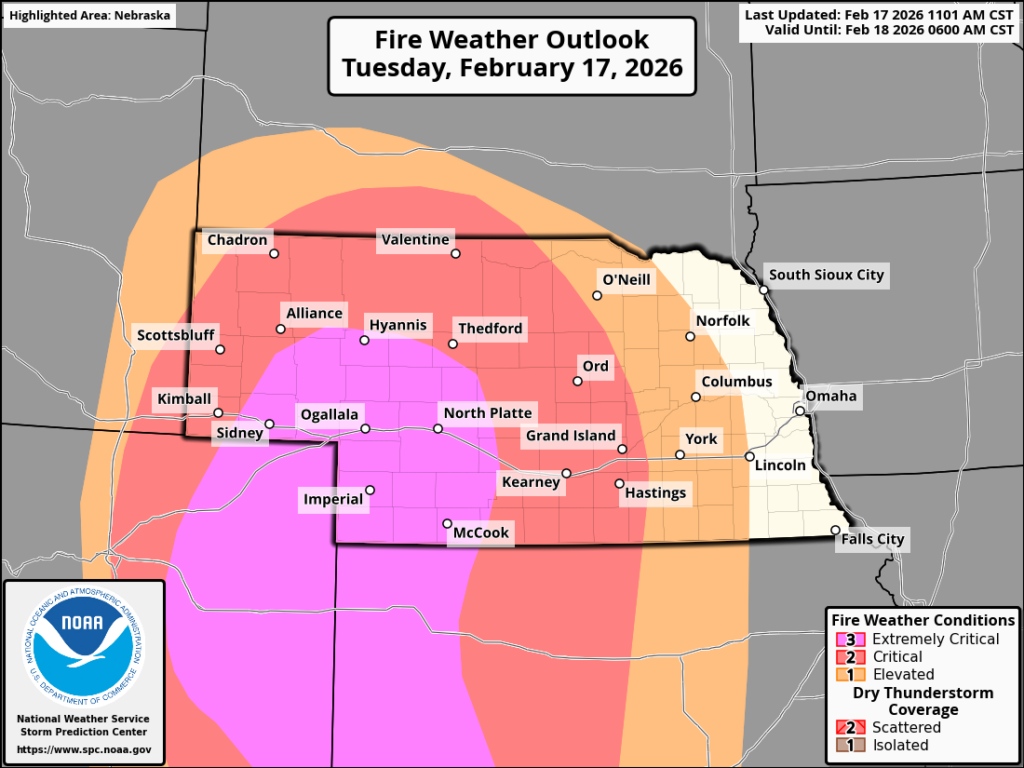

Fire weather is defined as “extremely critical” in western Nebraska, northwest Kansas, and northeast Colorado today, a high-end day for this region.

Overall, today is one of those days to be extra careful with flammable material risks.

Deadpool

There is big news regarding the Colorado River right now, and I will continue to insist this is the biggest story most folks outside the West are not hearing about. Valentine’s Day was the overtime deadline for the Upper and Lower Basin states to reach an agreement on modified water use, replacing the one that had been governing the Basin since 2007. The states had until November to reach an agreement, which was extended to this past weekend, and we’re still at a stalemate. To give you some perspective here, the states have been in negotiations for two years now, and we’re still not really getting anywhere.

Jonathan Thompson at The Land Desk lays out where we stand right now.

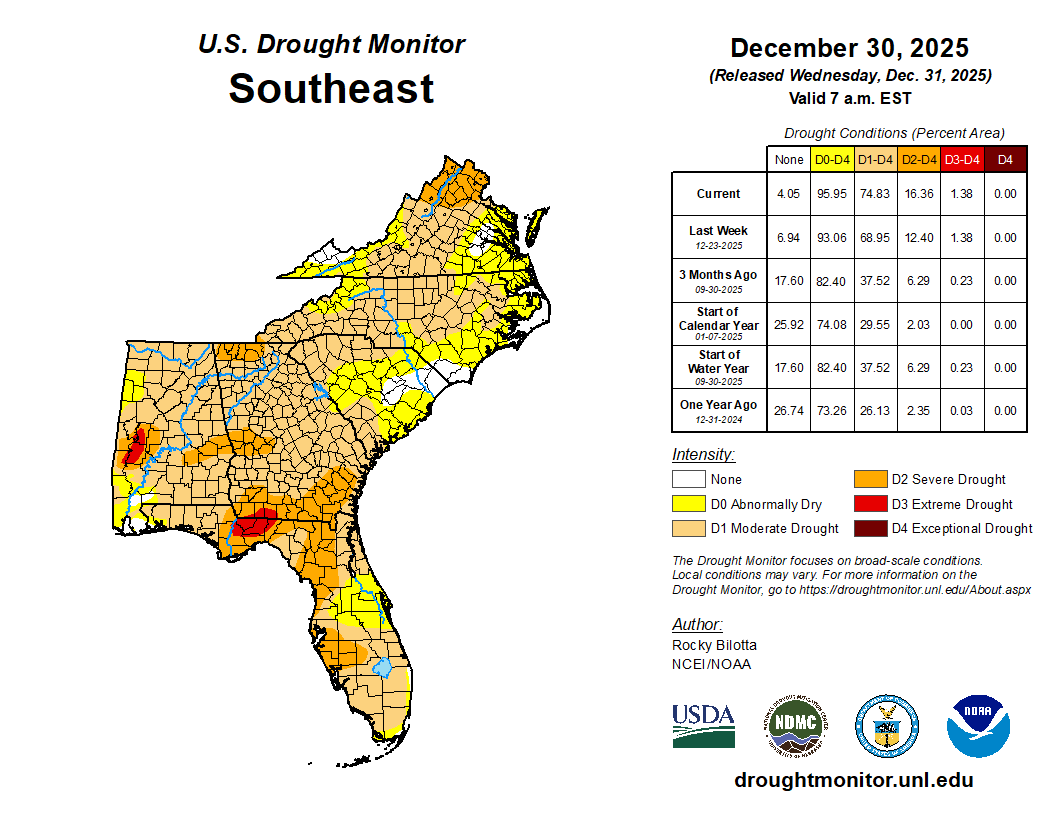

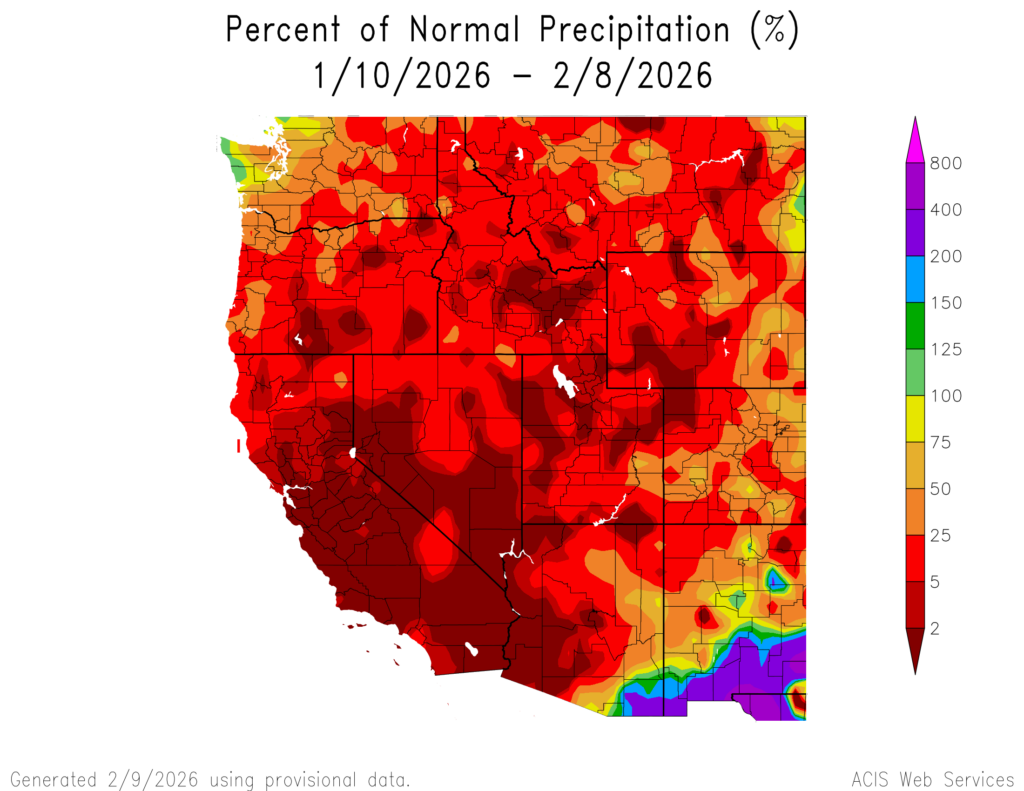

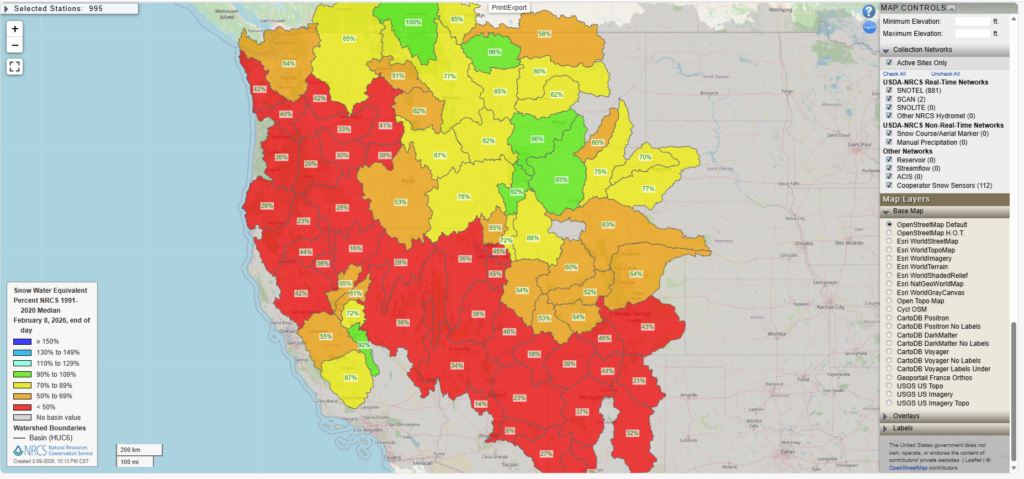

To call this a “crisis” is not hyperbole. Given the dreadfully low snowpack this winter in the Colorado Basin, with the upper basin running near record low levels and the timing of this arriving trainwreck, it’s very bad news. The Bureau of Reclamation believes Lake Powell is going to drop below the minimum power pool before the end of 2026, essentially dead pool. The problem right now is that the Upper Basin states (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico) don’t want to take mandatory cuts in their water use. They contest that they’ve done enough, having dealt with water cuts in dry years because reservoirs do not serve them, they serve the Lower Basin states. Also, water users are smaller in the Upper Basin, so more work and effort is required to divert water than is the case in the Lower Basin, where you have large projects like the Central Arizona Project for example that can take smaller allocations. Read Jonathan’s article for more on how this all could play out and why the Upper Basin may be forced to do something or face litigation.

He also has a great “101,” a primer on the Colorado River here.

I have curated a list of books on Western water issues on a Bookshop affiliate site if you want to learn more about the long-term issues at play here.

Here’s some additional news from the national, upper, and lower basin perspectives on the revised compact negotiations failing.

A lot more to come on this.