In brief: A major winter storm is going to impact the Carolinas and Virginia this weekend, with significant snow, wind, and tidal flooding. Behind the storm, the coldest air mass in over 15 years will settle over Florida leading to an extremely serious freeze there. All that and a dispatch from the annual meeting of the American Meteorological Society.

Good Friday afternoon all. First off, I do have to apologize for a lack of posts. My day job requires significant time investment off hours when weather gets serious in Houston, and with the threat of ice last weekend, I was completely void of free time. This week also marked the annual meeting of the American Meteorological Society here in Houston. I’ve been quite involved in organizing and planning sessions and socializing with colleagues in the community. More on both of those items below.

Weekend storm

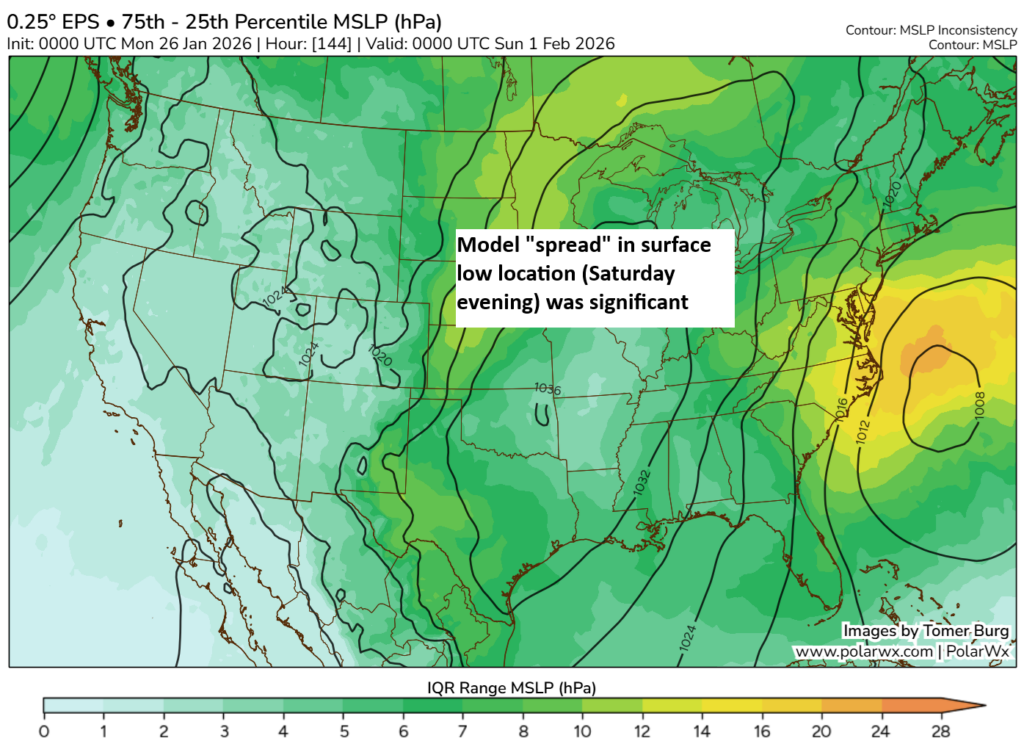

As many of you have been tracking through the week, a massive storm is going to blow up off the Mid-Atlantic coast beginning tomorrow. It has been a week of nauseatingly challenging changes to the forecast track. I want to step back real quick. Let’s go back to Monday’s 00z European ensemble run.

If you look at the spread in interquartile range between the 75th and 25th percentile sea level pressure forecast from back on Monday, you can clearly identify a rather large spread off the Carolina coast. The mean position of the low is actually not far off where it should ultimately locate. But in general, it was pretty evident that there was a significant degree of uncertainty. That uncertainty expanded on Monday then contracted later Tuesday and Wednesday. And now we’re focused on a southern track storm.

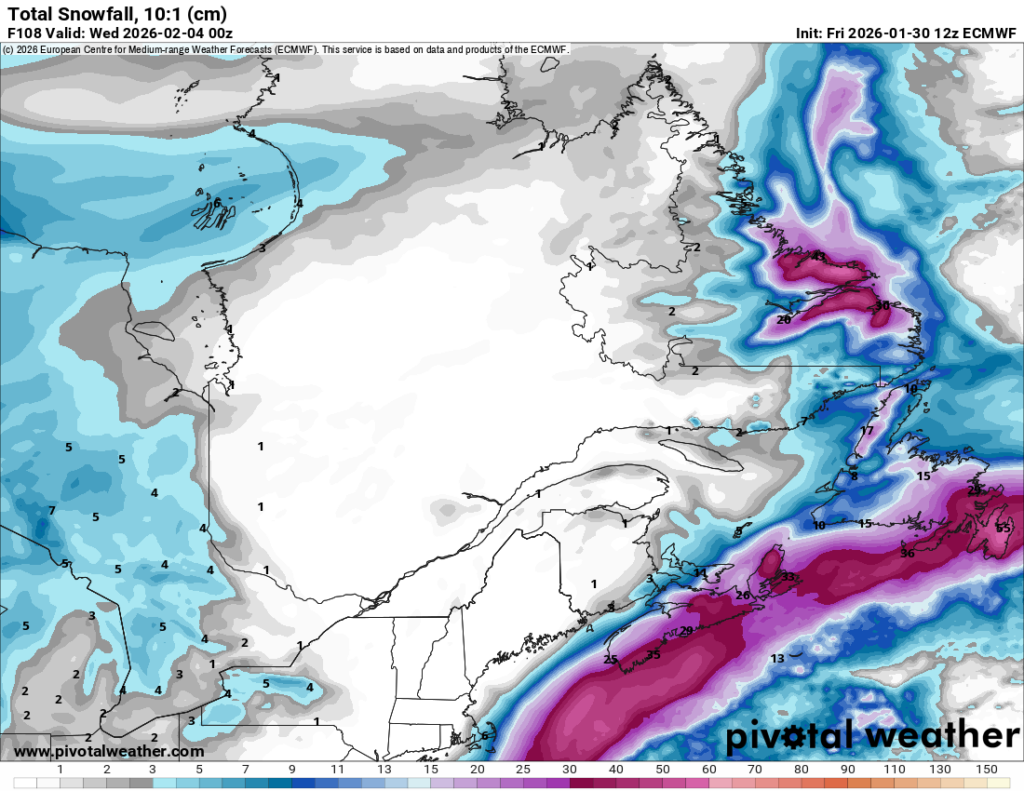

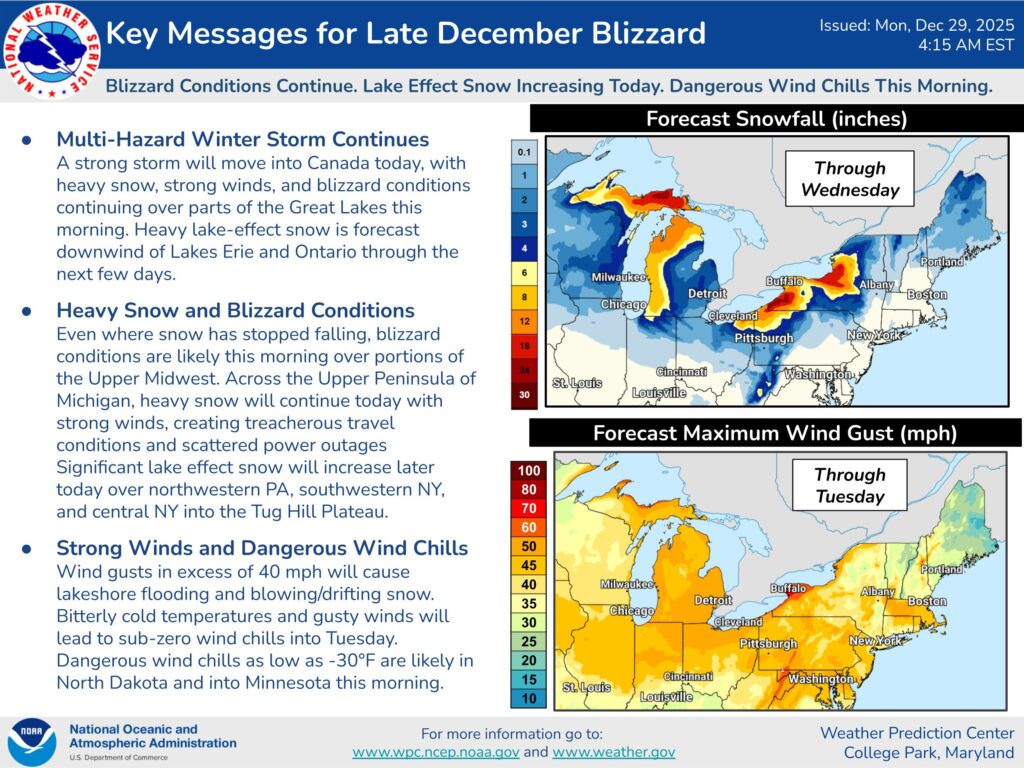

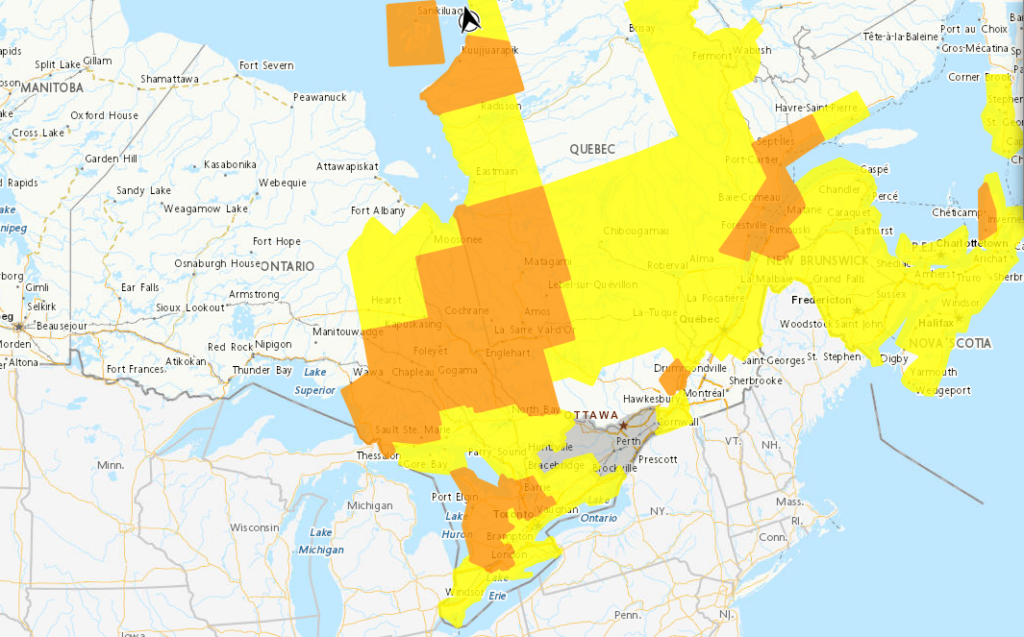

In general, the storm should develop and intensify off the coast of Capes Hatteras and Lookout. It will then move east-northeast out to sea rather than up the East Coast, at least initially. High pressure in the upper atmosphere over eastern Canada will help suppress the storm a bit. Eventually, the low finds its way into the Canadian Maritimes likely bringing blizzard conditions to parts of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.

To be clear, the term “bomb cyclone” and “bombogenesis” are valid here, but this is a strong nor’easter. The other terms reference specific meteorological definitions of intensification and sound cool. Otherwise, they’re meaningless. A cyclone “bombs out” if it strengthens at least 24 millibars in 24 hours. This one deepens from about 1010 mb once offshore tonight to about 976 mb tomorrow night, a drop of about 34 mb. That’s a bomb. It’s also a strong nor’easter.

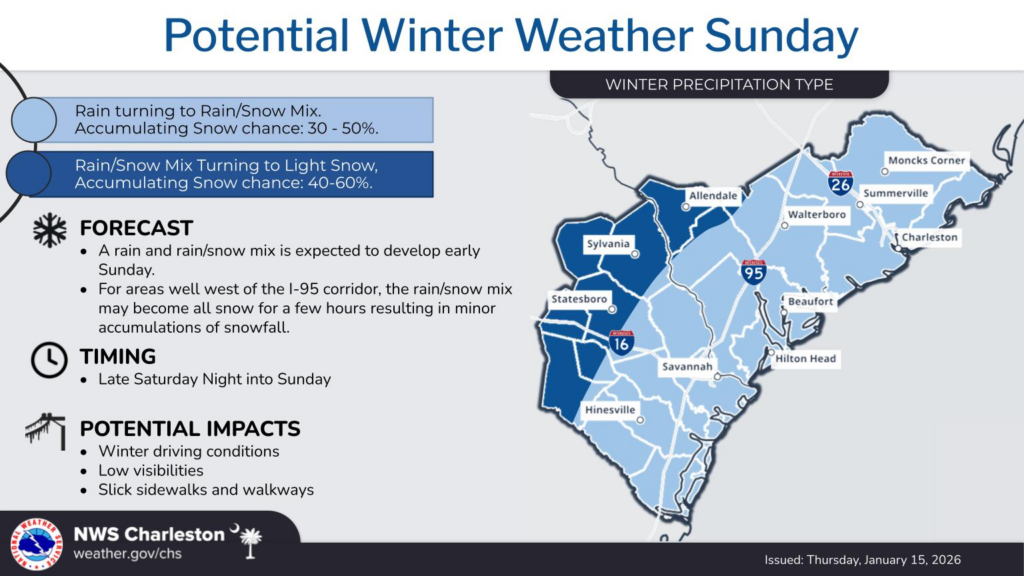

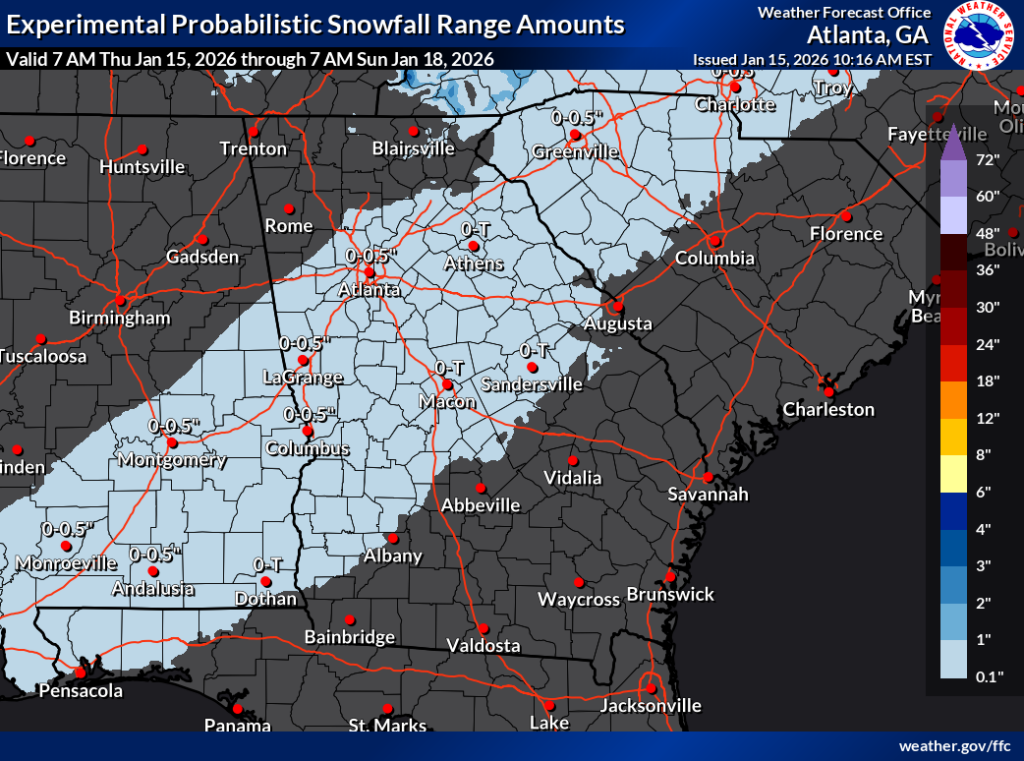

So what sort of situation are we looking at here? A lot of snow for the Carolinas and southeast Virginia.

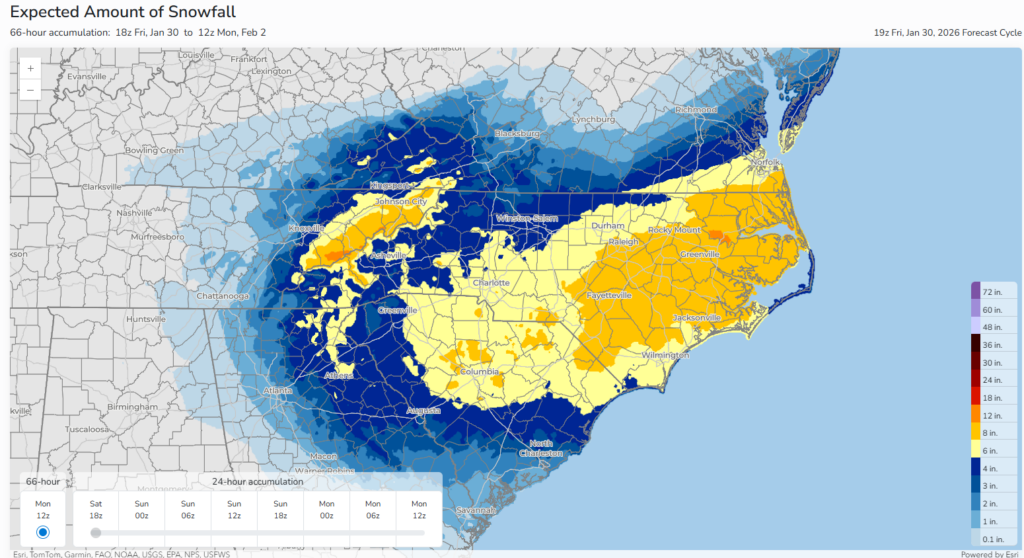

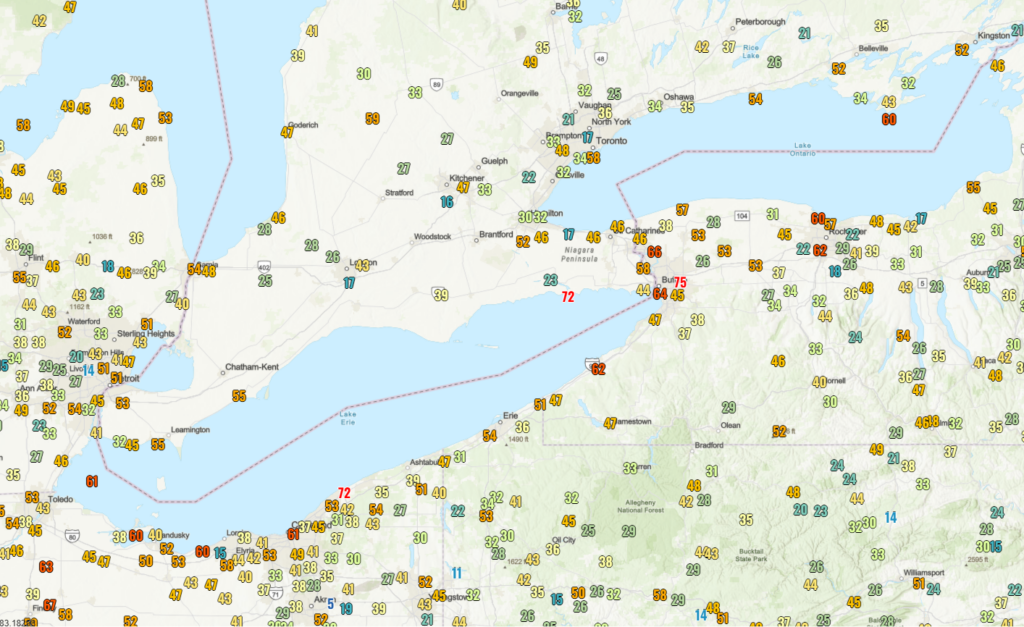

The snowfall forecast suggests a wide swath of 6 to 12 inches from Columbia, SC through Fayetteville and toward the Virginia Tidewater. There are signs of potentially higher amounts embedded within that. It is possible that we see some lower amounts too, but the probability of seeing 6 inches or more of snow is basically 60 to 70 percent or higher for the orange shaded regions. Either way, this looks like a very impactful snowstorm for the Carolinas and southeast Virginia.

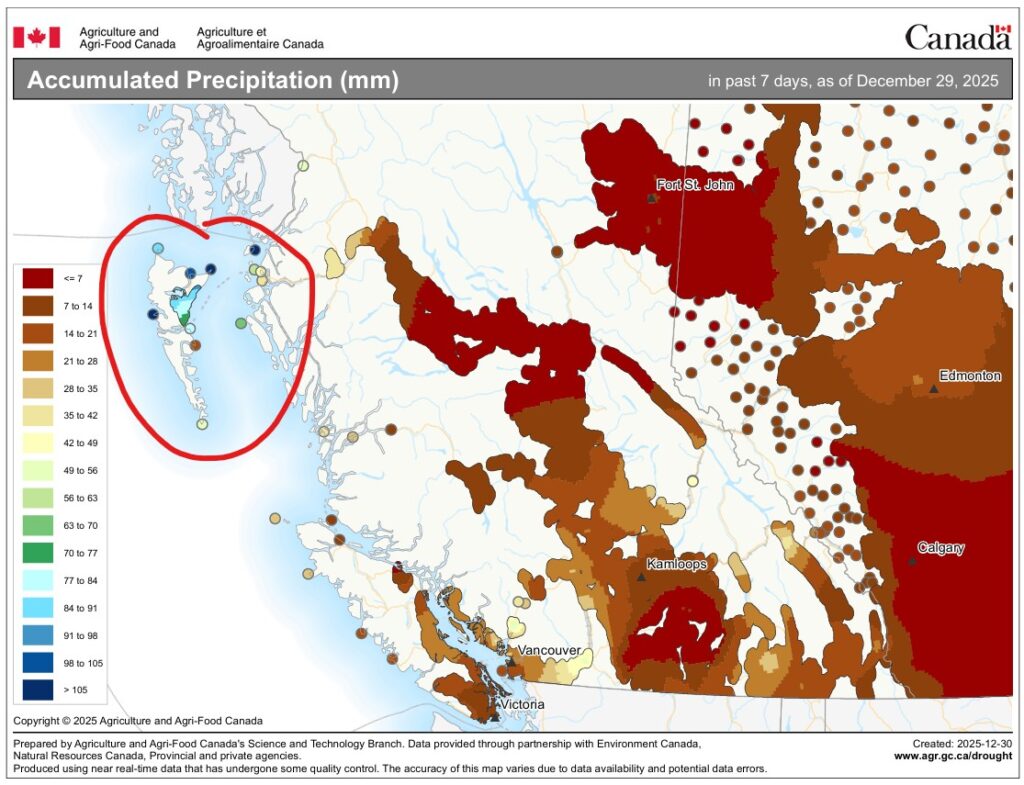

Farther north, there will be significant snow in the Canadian Maritimes as well. Anywhere from 20 to 30 cm or more of snow is likely between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, particularly the Avalon Peninsula.

Blizzard conditions are likely in some of those areas with the combined wind and snow.

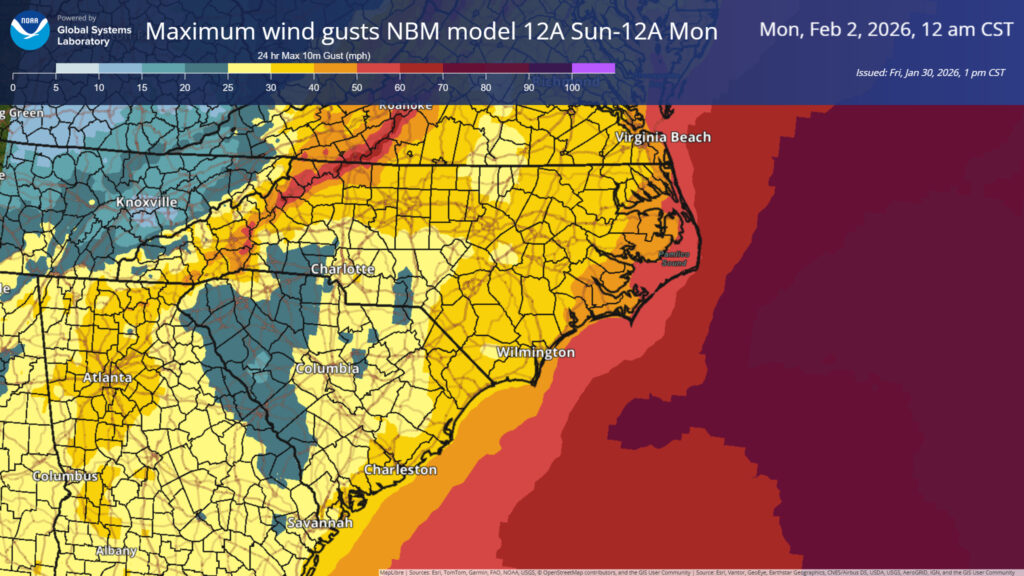

Speaking of winds, max wind gusts are expected to be on the order of 50 to 60 mph on the coast of North Carolina and Virginia.

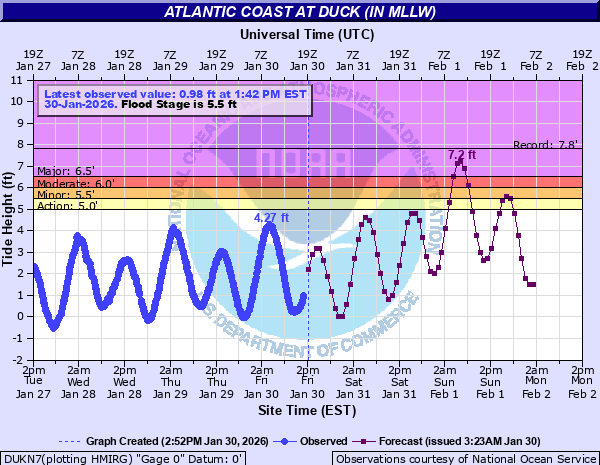

Current tidal forecasts suggest that the combination of winds and seas will lead to minor or moderate flooding on the soundside of North Carolina and major flooding on the oceanfront, particularly the farther up the coast you go. The tide forecast at Duck, NC shows a 7.2 foot tide level for Sunday morning’s high tide.

To put this in perspective, the forecast at Duck is higher than any of the tropical events this summer and the highest since September 2019, or during Hurricane Dorian. The only other higher tides were with Isabel in 2003 and during the powerful November 2006 nor’easter. The tidal forecast farther up the coast in Virginia is more in line or slightly lower than this past summer’s tropical events.

So, bottom line: Wind, cold, and snow. Minimal ice is expected but sleet or plain rain may mix in closer to the coast of the Carolinas.

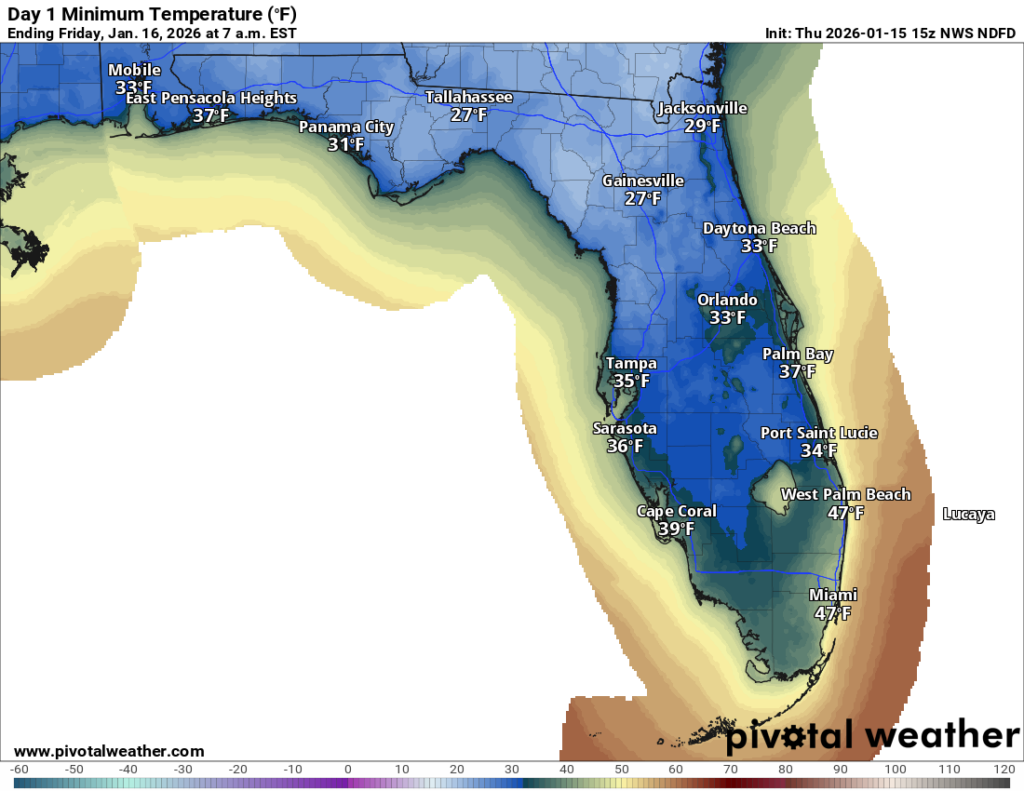

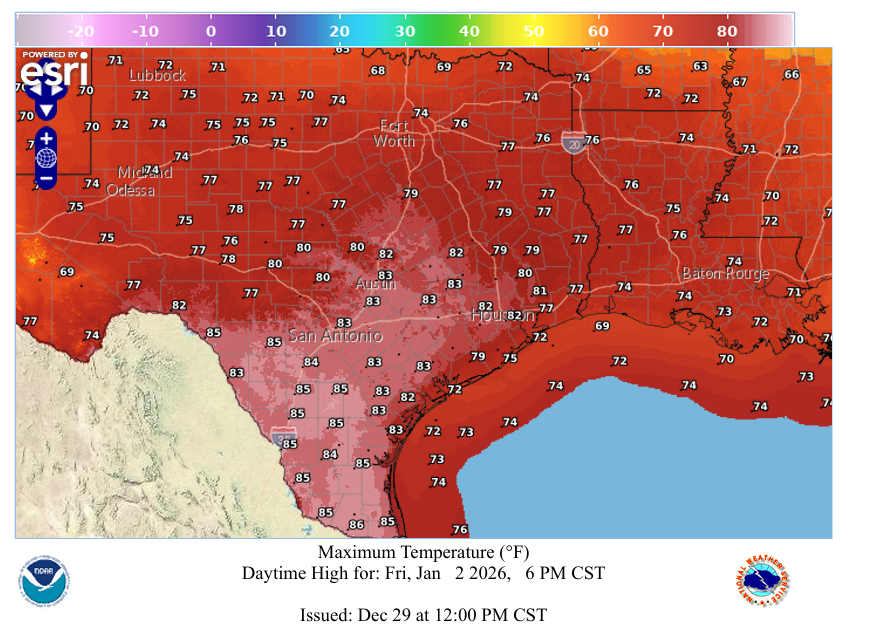

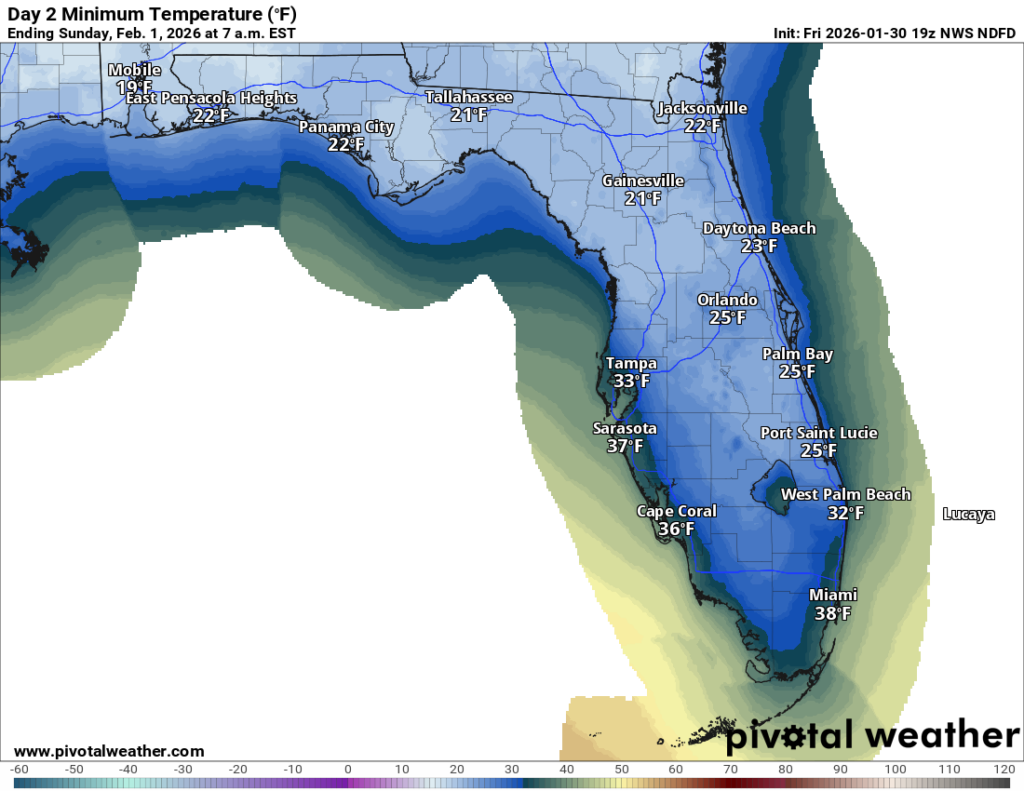

What about cold? On the backside of this storm, some intense cold air is going to drop into the Southeast. Dozens of records may be threatened, particularly farther south away from the storm into Georgia and Florida. Sunday morning’s low temperature is forecast to be 25 degrees in Orlando, 22 in Jacksonville, and 32 in West Palm Beach. Even Miami gets down to 38 degrees. If that happens, it will be Miami’s coldest morning in 16 years.

This will be a severe freeze for the state of Florida.

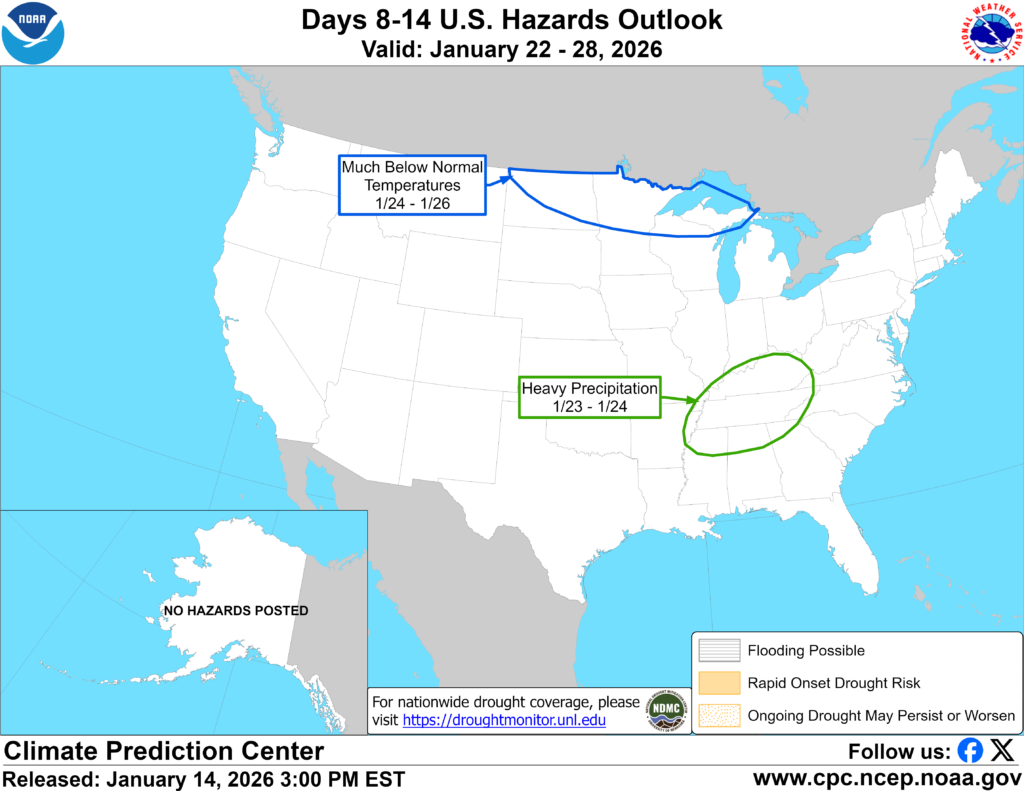

Cold weather is expected to continue in the East for a while longer however. We may not be done yet.

Ice storm recovery continues, and I encourage you to check out Alan Gerard’s Balanced Weather for more on the impacts and recovery.

AMS Annual Meeting Takeaways

Lastly, the American Meteorological Society, the largest professional organization for meteorologists held their annual meeting this week in Houston. I attended this event and talked to numerous people about the state of affairs right now. A few quick observations I feel are relevant for the general public to understand:

First, the students and young, early career professionals in our field are exceptionally optimistic and motivated. I heard so many students say that their dream jobs are at the National Weather Service or in broadcasting. Both of those areas have seen an exodus of talented individuals in recent years, with NWS accelerating in the last year. Despite all the struggles and hurdles in last year, these students are still committed to serving the public, and I think that’s amazing.

Second, also despite the hurdles and challenges, the science is enduring. Research does continue, though it is handicapped and being slowed down. But in general, the work continues. And while I won’t say the vibe is optimistic, it is focused on the tasks at hand.

Third, there is grave concern about NCAR being shut down, and there is great concern about what that means regarding a lot of the ongoing and upcoming research. While the work continues, losing NCAR, even if it means “redistributing” its mission to another agency would cause a lot of unnecessary headaches and seems to be a woefully inefficient use of federal resources. Make of that what you will, but it’s disappointing that the verbiage to protect NCAR was not agreed to in the otherwise pretty good appropriations bill passed by Congress.

A number of federal colleagues were not allowed to travel to the meeting, which was deeply felt for sure. The weather also played a role. But in general, I expected a slightly more negative, pessimistic vibe this week. While reality drives some of that for sure, the slightly more positive takes really stood out to me. We’ll see how it goes next year in Denver.