One-sentence summary

It’s November 30th, so today’s post will take stock of what was a very interesting hurricane season.

By the numbers

The 2023 Atlantic Hurricane Season was a busy one. It wasn’t so much that there were a lot of large storms; the season itself had “only” 7 hurricanes and 3 major hurricanes, which is spot on normal for a typical hurricane season. But we had a lot of storms that lingered for awhile, traversing the open Atlantic for a long time.

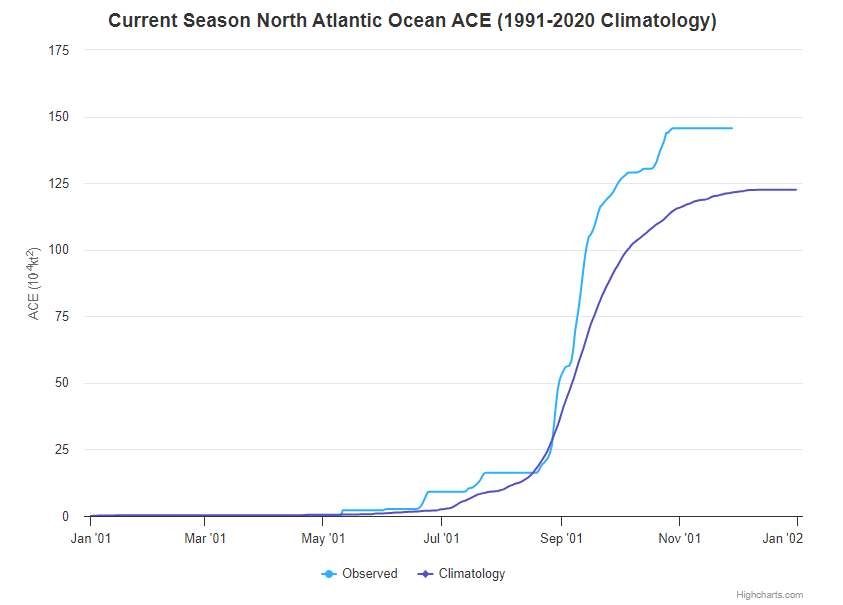

Recall that ACE, or accumulated cyclone energy is calculated using just the wind intensity and duration of a storm. It’s an inherently imperfect calculation, but it serves us well in terms of putting a season into context. Examples of recent seasons with ACE values in the “hyperactive” category include 2020, 2017, 2010, 2005, and 2004. Not many would argue that those seasons were anything but busy. 2023 falls into the next bucket of seasons, which are considered above normal. Our ACE will finish the season around 145.5 units, falling short of the 159.6 needed to be a hyperactive season.

Because of the duration of some of the stronger storms, the 2023 season certainly felt above normal. As noted, ACE is not perfect, but it tends to do better from a seasonal standpoint than number of storms. As our capability to name a greater number of storms increases, the actual storm count means a bit less than it used to perhaps. But ACE manages it better.

Speaking of, we will finish with 20 named storms this year. We managed to get to Tammy, leaving Vince and Whitney unused.

Why was the Atlantic so busy? Why were the Gulf and Caribbean not very busy?

Let’s talk for a quick moment about what happened this season. From the map at the top of this post, you can see that the amount of traffic in the open Atlantic was excessive. Other than Arlene, Idalia, and Harold in the Gulf and Franklin and Bret in the Caribbean, all of the action was in the open Atlantic. So why was that?

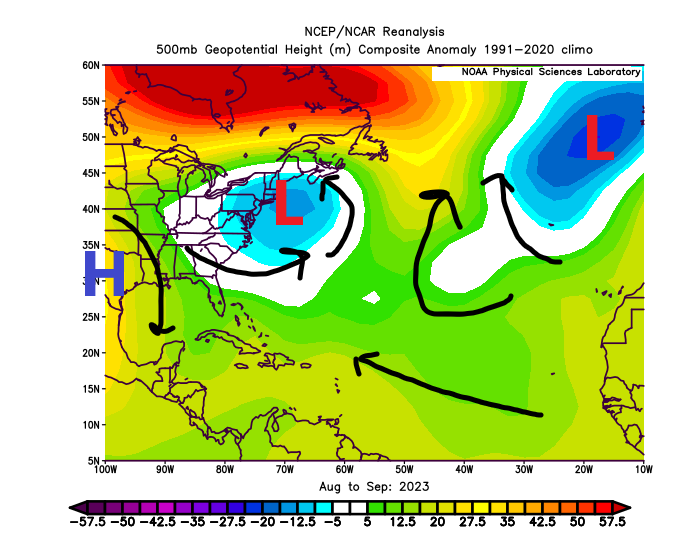

If you look at the upper air pattern for August and September, when 13 of the 20 storms occurred, you can sort of understand what happened. We’re looking 20,000 feet up here at what we call the 500 millibar (mb) level of the atmosphere. This is a good proxy for steering currents, or what will move tropical systems from point A to point B.

What can we make of that map? A couple things. Let’s work left to right on the map above. First, over Texas, high pressure was stagnant. It was arguably the worst modern summer in Texas history in terms of heat, but it did keep storms out of the western Gulf. So that kept that part of the basin quiet. For the eastern Gulf, we managed Idalia in there, the one bad storm that found its way northward into the U.S. But overall, most storms would have been directed northward off the East Coast based on this map due to pretty persistent low pressure in the upper atmosphere off the New England coast. This is also to blame for the extremely wet summer in that part of the world.

We also had low pressure northeast of the Azores. When you have low pressure systems like that one and the one off New England, you are often going to induce a poleward motion to the tropical system. In other words, they feel the “pull” north. All tropical systems generally track west, then north, then northeast in Atlantic (with plenty of notable exceptions). But on the long-term average, that’s what we see. In this case, they had help this season, and that’s why so many “fish” storms occurred and so many impacts to Bermuda occurred out in the open Atlantic.

Did the much hyped warm oceans play a role?

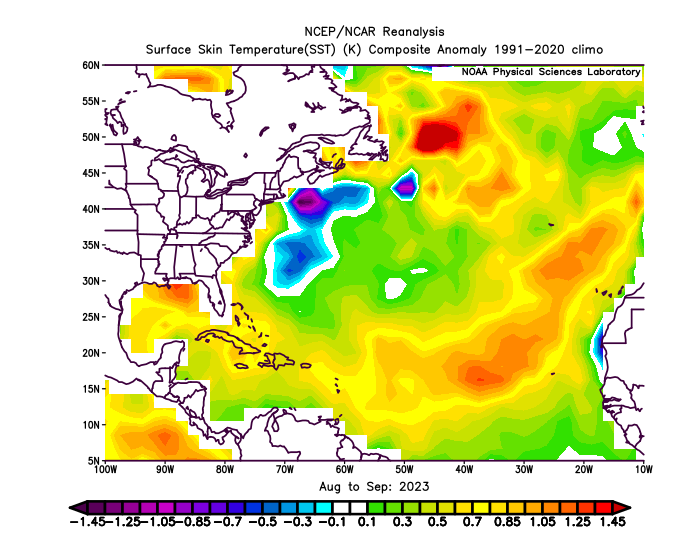

When the season began, one thing we honed in on right here in The Eyewall’s early days were sea-surface temperatures. The Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the Gulf were all record warm at times this hurricane season. The August and September mean of sea surface temperatures (SSTs) was above normal virtually everywhere. Why is there that pocket of so much cool water off New England and southward? Hurricanes Idalia, Franklin, and Lee all worked to basically devour all the warm water there.

When the season began, we noted that the extremely, if not record warm SSTs were enough reason to justify an active hurricane season forecast. Many articles were written across the media about this. And indeed, that is what allowed most seasonal hurricane forecasts to come close to verifying this year. Instead of the 16/7/3 consensus forecast for the season, we got 20/7/3 for our storm/hurricane/major hurricane slash line this year. I will say this: It takes courage to call for an active hurricane season in the face of one of the strongest developing El Niño events in recent memory. So kudos to those that stuck to that logic, despite what history has told us about El Niño.

What about El Niño? Did it matter at all? What else?

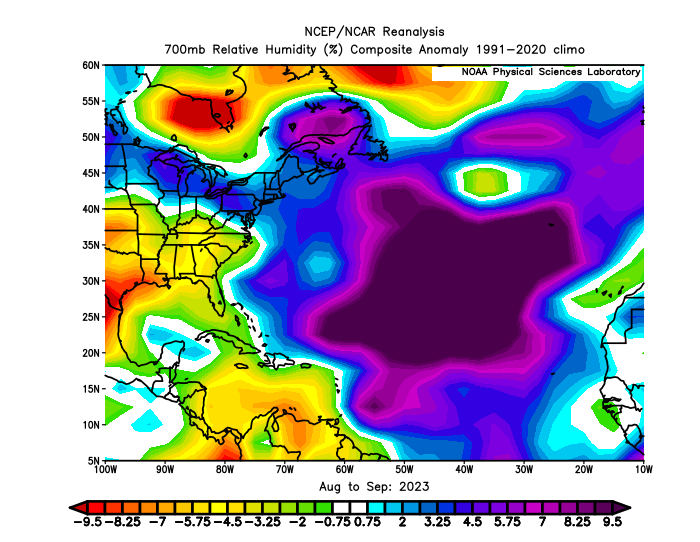

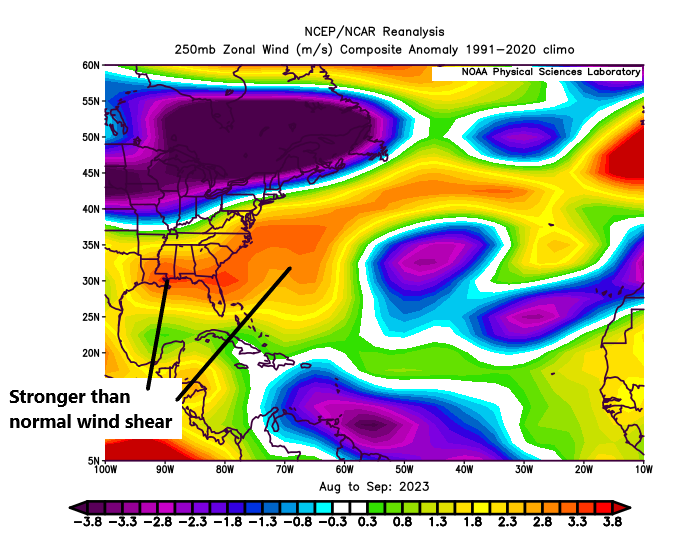

The answer to whether El Niño mattered or not this year is “sort of.” Wind shear is usually enhanced during El Niño summers, especially over the Caribbean. That did not actually happen, but we did see very strong shear near the Gulf Coast this season.

While I think that was notable, the dry air in the western part of the basin didn’t hurt. With high pressure dominant and so much drought development on the Gulf Coast this summer, it definitely worked to help mitigate any storms.

So it was an interesting season. It’s worth noting that the average of the strongest El Niño hurricane seasons (taking the July-September ONI from NOAA) was 9 storms, 4 hurricanes, and 1 major hurricane. Suffice to say, 2023 will go down as one of the most active El Niño hurricane seasons ever recorded. That’s a little concerning given that an El Niño of this magnitude is usually enough to mitigate things. That only partially happened this year, in part due to the extreme warmth in the Atlantic. So does that mean that if we live in a world of more permanently warmer SSTs, El Niño might not matter as much when it comes to hurricane season? It’s a tantalizing and unsettling question, but it’s one we should be asking.

Thanks to those of you that joined us on this journey for the hurricane season and put your trust in our commentary. We are appreciative of your support. The Eyewall’s parent site, Space City Weather is holding a fundraiser for a couple more days. Any contributions you make will go toward both sites. If you feel compelled, click here to donate or purchase some Houston-focused swag. Thanks for considering! We will be back from time to time through winter with an update on big weather when we can. Stay with us, and enjoy the non-hurricane season!

Very helpful big-picture overview. Thank you!

Thank you for being there this hurricane season. I feel that I learned so much I didn’t know before!

Thanks from this Tampa-area guy for your insight during the season. Just made a small donation to help you guys keep doing your great work.

I am so glad hurricane season is coming to an end today. I relied on you through out the season to give me and my family the best hurricane news. Excellent reporting. Thank you, and I bought a tee from the fund raiser.

I’m totally psyched for next hurricane season! It can’t get here soon enough!

I am so glad I discovered the eyewall and was able to keep up with our hurricane season here in Houston area. Just want you to know how much I appreciate your website.

THANK YOU!

Thanks that focused and wider view is very valuable.

Excellent reporting. Easy to understand and very informative