We have a lengthier post than usual today to catch you up on the doings of the Atlantic, which may be opening its doors to business this week. We’ll call it a soft opening for now. Just a reminder that you can subscribe and get these posts in your inbox, by signing up for email updates to the right (on desktop) or at the bottom (on mobile).

Also, give our social channels a follow:

Facebook

Instagram

TikTok (Matt tries to post an update each day)

Twitter

Threads (the Meta Twitter competitor)

Bluesky

Mastodon

And a reminder that we’re here to cover the entire Atlantic basin, not just the Texas coast.

One-sentence summary

Hurricane season should pick up some later this week, with one or possibly two systems potentially trying to develop in the eastern Atlantic.

Happening now: Peak season begins this week. Maybe.

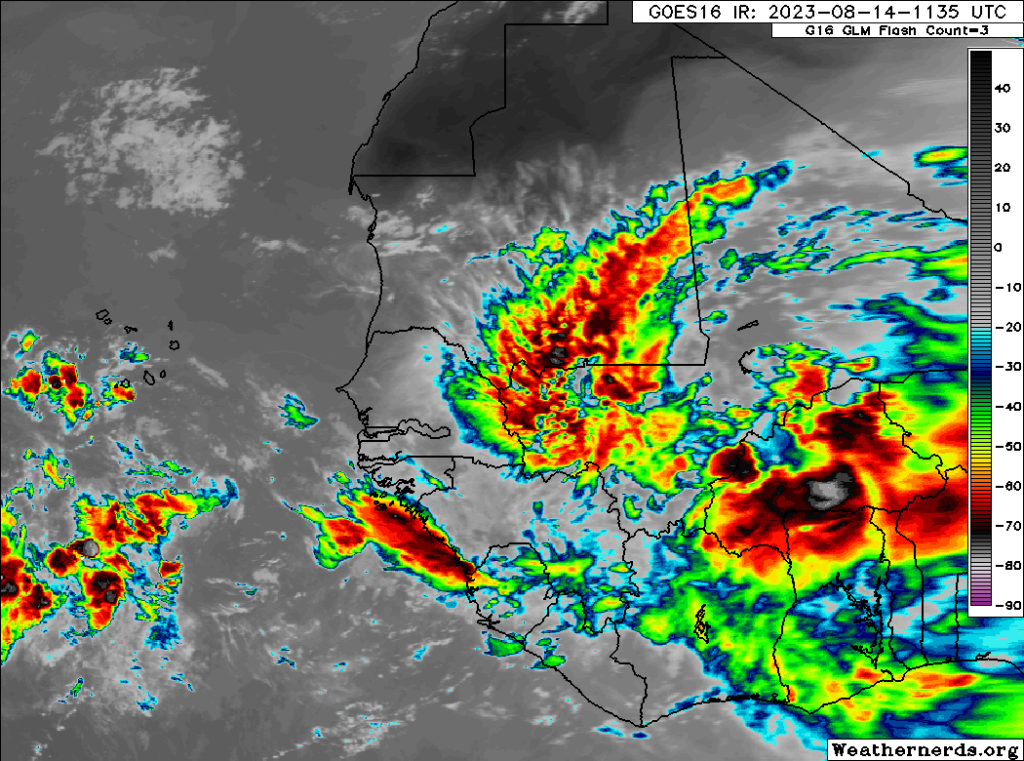

The tropics look to remain quiet the next couple days at least, but as waves begin to emerge off Africa this week, we’ll watch the late week period for the potential of some development. If we look at the satellite imagery over Africa this morning, we can see the beginnings of this burst of activity.

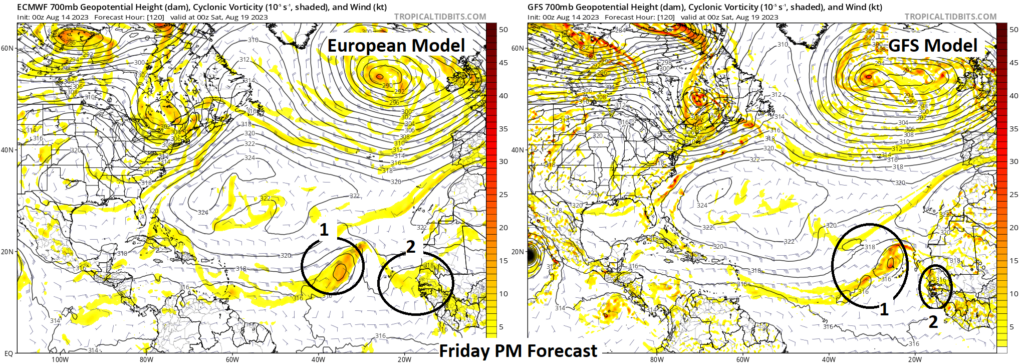

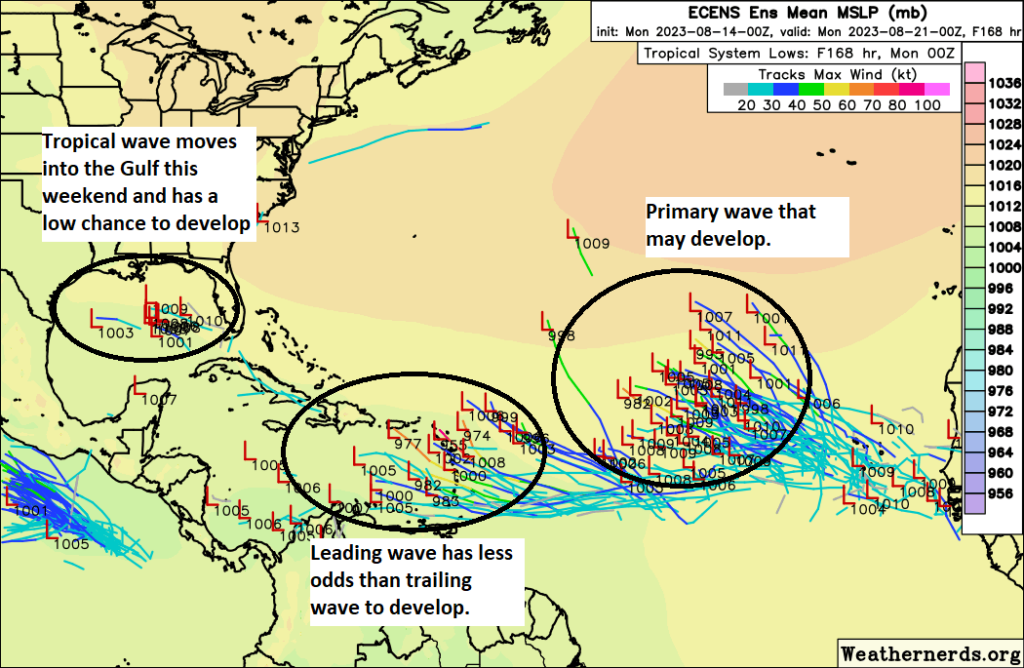

From this morass, we expect about two primary disturbances to show themselves. Both the GFS & European models are now in decent agreement on that for day 5.

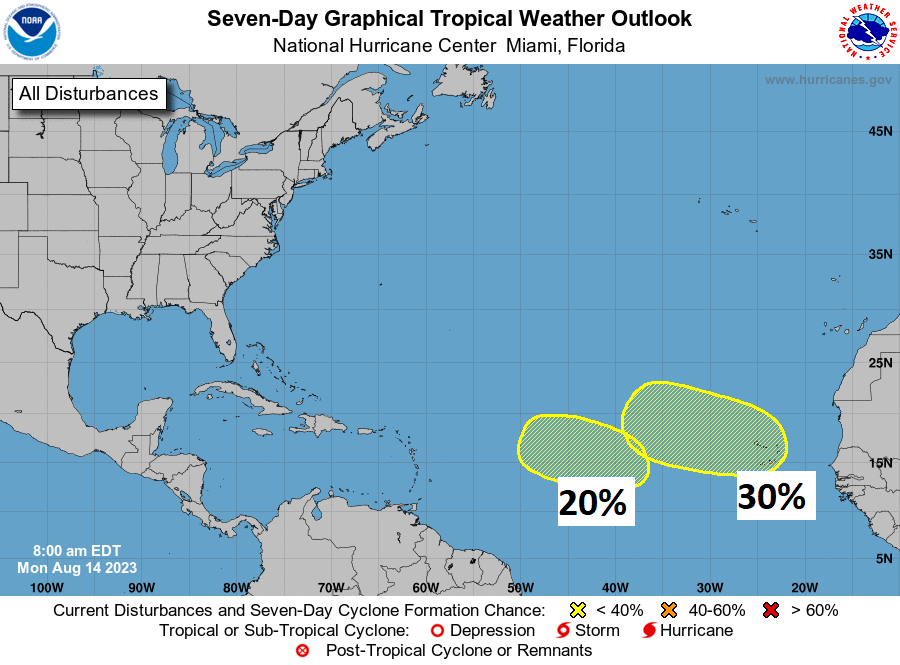

The eastern Atlantic seems to be the most likely area for development to occur at the tail end of the near-term period, and it would likely be one or two waves that could do it. That being said, there is going to be a lot of “noise” out there with this stuff. You really need these disturbances to break out of this noise to have a good shot at developing; destructive interference can be a thing. The National Hurricane Center currently has odds of 30 and 20 percent for these disturbances to develop in the next 5 to 7 days.

I would say the odds of one system developing is probably above 50 percent right now. The odds of two systems developing is probably 20 percent or less. Either way, we at least know where to watch this week. We’ll talk about the future of these waves below.

Elsewhere, the European model is slightly bullish on a third piece of activity that makes it close to the Lesser Antilles later this week. I would say the odds of that area becoming something are extremely low right now, so we’ll leave it at that. There is another tropical wave that should make it across the Caribbean or end up near the Bahamas later this week as well, but that will not develop this week. More on that one below.

The medium range (days 6 to 10): An in-depth look at what will drive the bus in the Atlantic

So, with so much noise heading into the period and two dominant features in the eastern Atlantic to focus on, let’s check up on three things to see how this might go: Steering currents, dust/dry air, and wind shear.

Steering currents

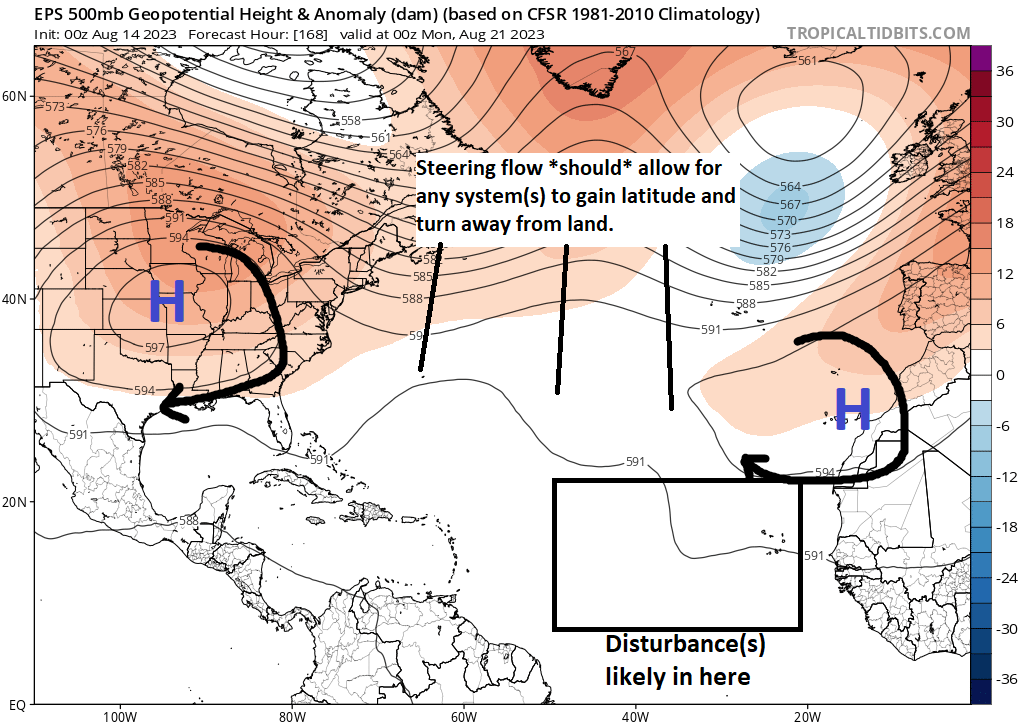

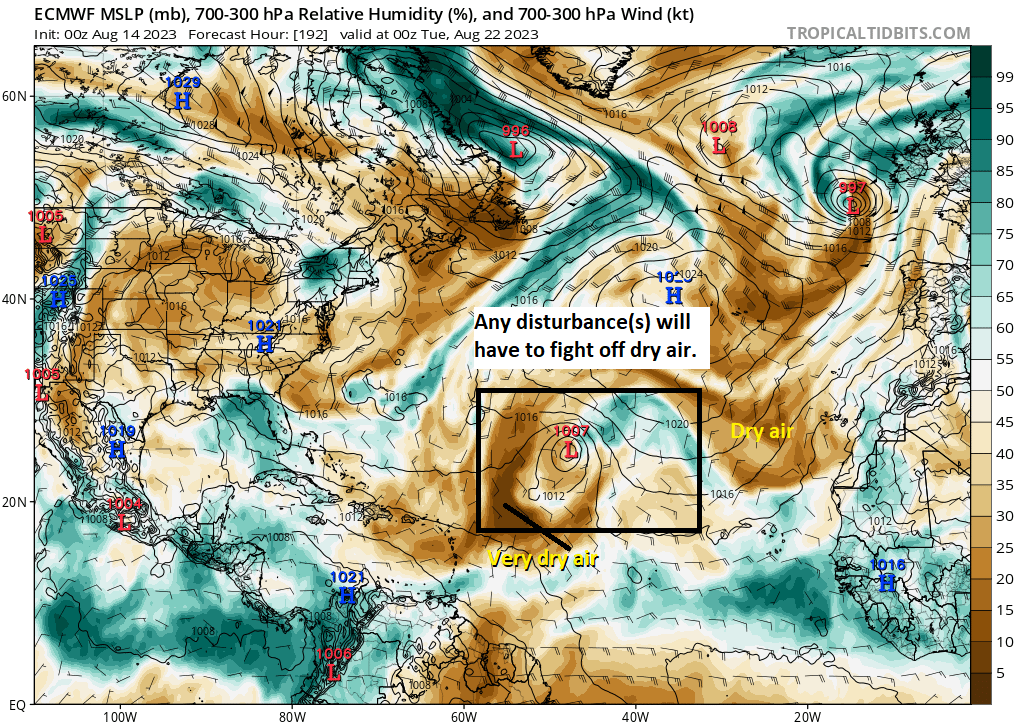

Where will these systems go? Beginning later this week, high pressure over the central Atlantic will begin to weaken. By Sunday (day 7), we have a map up at 20,000 feet in the atmosphere that looks like this:

High pressure has reformed itself by then, somewhere south of the Azores or near the coast of Africa. What does this mean? Well, at first, given the weaker high pressure, we’ll probably see any system(s) in the eastern Atlantic turn to the northwest fairly quickly, particularly if they form quickly. As that happens and the high re-strengthens, that system or those systems will probably get pushed back to the west some. The good news is that it does not appear (for now at least) that the high pressure area will build west as the potential system(s) comes west. This should keep the exit door open to the northwest and north in the Atlantic. The vast majority of ensemble data suggests this to be the case as well. Ensembles give us 30 to 50 runs of the same model with tweaks, so we get a realistic “spread” of options, and in this case, almost all take it out of the way.

The ensemble here is saying to us “Hey, you’ve got a tropical wave here that has a shot at developing, but it will probably turn northwest before it really gets to impact any land.” We expect that it will turn north right now, but we are not sure exactly when. Obviously we will watch this closely, but for now at least, we think this will turn northwest.

Dry air and dust

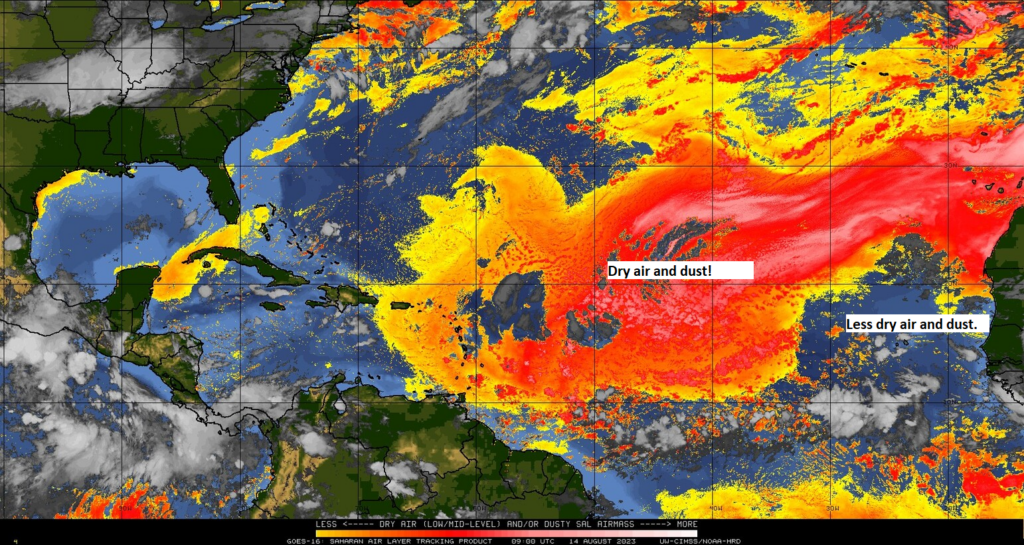

There is an awful lot of dry air and dust in the Atlantic — right now.

But notice how it relents some near Africa. Initially, dry air probably won’t be a huge obstacle to overcome. But, if you trust modeling, the dry air is going to be a feature, not a bug.

Above, you see a map of mid-level atmospheric moisture on day 8, next Monday. If we box in the area where disturbances *might* be, and then we delineate dry air from moist air, you can see that there’s definitely dry air back in the vicinity of where this system or these systems may be. Tropical storms do not like dry air. It inhibits their growth and development. Assuming dry air is nearby, then you may have a situation where there is a “cap” on how strong these systems can get.

Shear

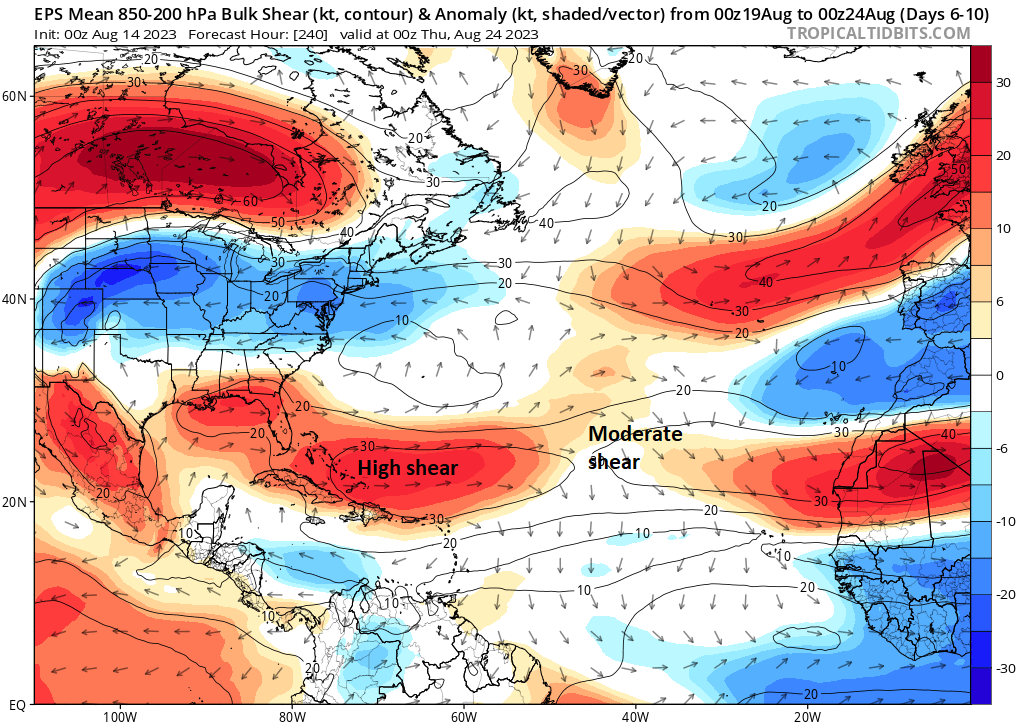

Another reason to potentially keep a lid on the ceiling for whatever forms is wind shear.

The wind shear anomalies shown above for the medium range period are less than optimal for tropical storms to develop and strengthen. Wind shear is when winds move in varying directions with height, something that’s not great for hurricanes. The less wind shear, the more hospitable the environment is for tropical systems to grow. For now, this is an okay looking map if you’re rooting against storms.

As always, there are exceptions to the rules, but I think when you look at the sum of the parts right now, between shear, dry air, and the steering pattern, we are not in terrible shape in the Atlantic basin, despite the noise from modeling over the next 10 days.

Elsewhere

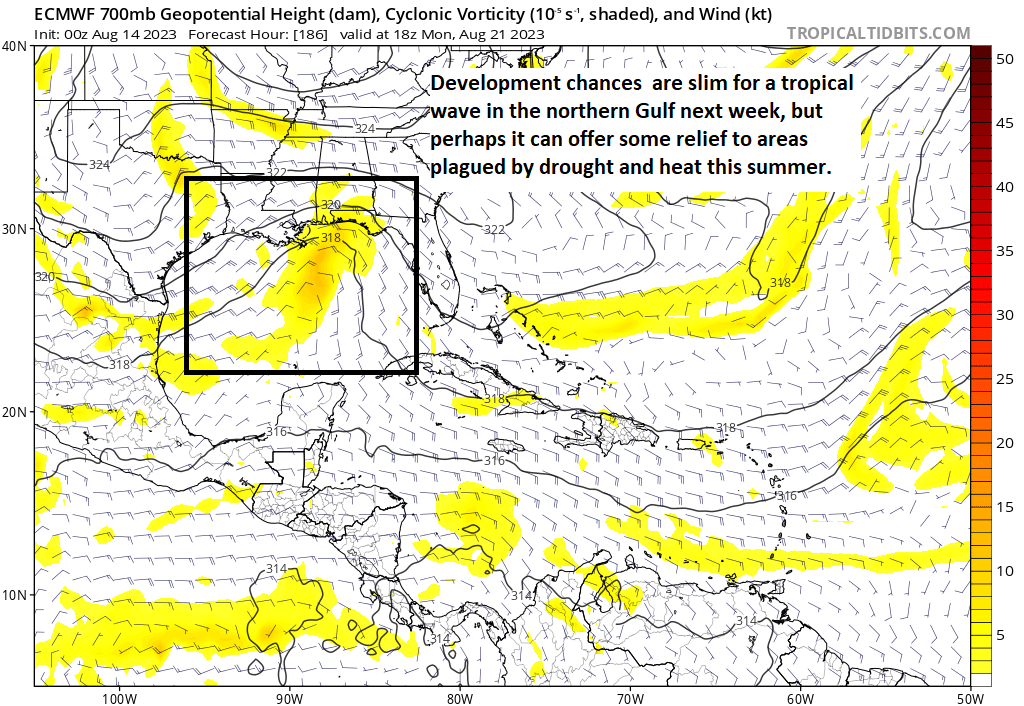

Aside from all this, we will have to wait and see if there is any consistency from models on the potential that the lead wave today can manage just enough to survive into the Gulf and then develop, something operational models show to some (modest) extent.

The upper pattern may support the Gulf being open for the Mexico or Texas coast next week, with high pressure centered over Missouri, farther north than it has been most of summer. The question as always is can we do anything with it? We’ll discuss that more through the week.

Fantasyland (beyond day 10): Active pattern may continue

As of right now, there are no specific concerns in the Atlantic heading out into the longer range. I do believe the pattern will remain fairly active, but the question will be whether or not the hurdles of shear and dry air will be low enough for storms to overcome. We’ll have to wait and see.

Seeing all the dead grass around Texas, I am kind of hoping that disturbance hits (not too directly) and widespread showers form over the oven baked area, but I also don’t want it to explode in the sauna that is the Gulf so I’m also counting on that shear to weaken it quite a bit.

I will take dead grass over anything tropical. I don’t care if we have dead grass til November.

I’ll take a mild tropical situation over wildfires.

Thanks for the very interesting explanation of our weather systems!!

I’ll take a few more days of this awful heat if that keeps the tropical bad guys away

*complicated*

ty for untangling everything – so glad you’re here ☺️

hopefully it will all blow over 🌬

I want to forward The Eyewall to some friends but don’t see the Subscribe link at the bottom. I see Unsubscribe and Manage. Is it just me?

Thanks, as usual, for all your work.

Click the 3 dots upper right corner and share away.

Best bet is probably to send your friends a link to the site, and just tell them to sign up if they’d like. Or try loading the page in an “Incognito” or “private browsing” window. It may just recognize that you have already subscribed. Thanks for reading!!

I am seeing many GEFS ensembles in the Gulf in “Fantasyland”. Is their cause for concern in the coming weeks?

Not a serious concern right now. There’s noise out there, but I think there’s a lot of reason to be skeptical that it’s going to be quite as crazy as some modeling has shown.

I have a feeling that I’m about to ask a common question, but I haven’t found an answer. — I’ve seen about unprecedented warmth in the Atlantic, but this mentions dry air. Warm water evaporates easier, & dry air promotes evaporation. So why hasn’t the dry air headed out into the ocean & promptly gotten humidified?

It’s not a common question actually, and I think it’s a good question. Yes, in theory, you would assume that as dry air moves over the warm, humid oceans you’d modify or moderate the air mass to be less dry. My hunch is a couple things. Saharan dust is one way to get dry air, and that’s a bit unique, so I don’t believe it moderates easily. So I think we see a bit of that out over the Atlantic. Second, I think some of what you see in terms of “dry” air is on such a scale (air masses tend to be large) that any moderation is minor. And it may be that a lot of it *is* being moistened up but not to a point where it’s more humid than normal…just less dry than normal. Dry air = sinking air, or subsidence, and when that’s around on a large scale, it won’t just disappear. It’s all very complex!