The tropics remain quiet in the near-term and more interesting a bit farther out in time, though with no real concerns to any specific place at this time. If you missed it yesterday, we published our first real in depth piece which discussed the story of the Gulf of Mexico in recent years and what it does (and doesn’t) tell us about the future.

One-sentence summary

Over the next 7 to 10 days, the most interesting area to watch will be in the middle of the Atlantic and toward the Lesser Antilles, where there is perhaps a low chance of lower-end development.

Happening now

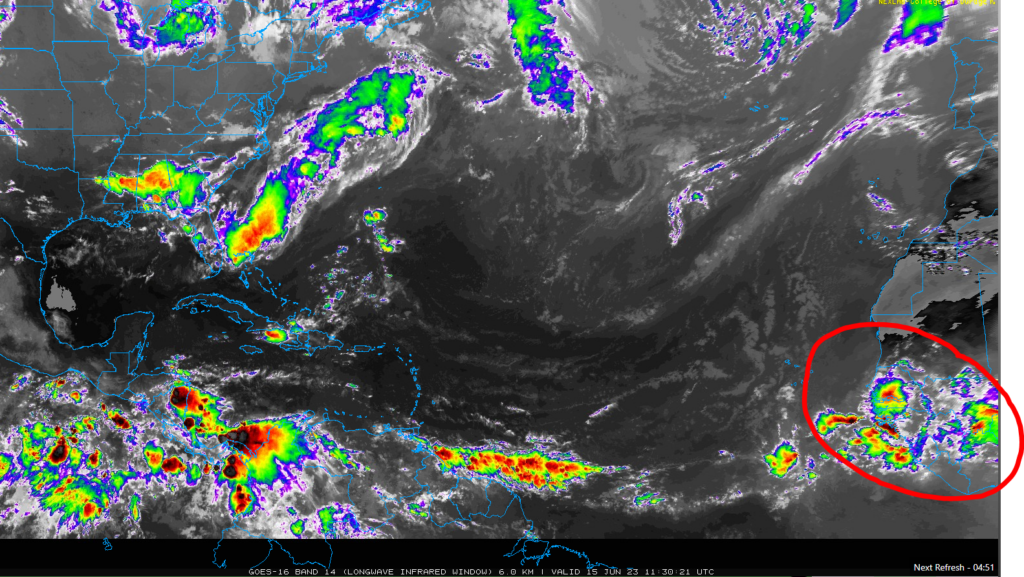

Over the next few days, we don’t expect much of anything to occur. If you look at a satellite image of the Atlantic, there’s nothing of note. Yes, there are storms off Florida and the Southeast coast, but they remain extremely disorganized. By next week, the circled area of thunderstorms over Africa may try to slowly begin developing as it moves across the middle of the Atlantic.

But, that’s more of a medium range story, so let’s shift to that section.

The medium range (days 6-10): An odd area to watch in June

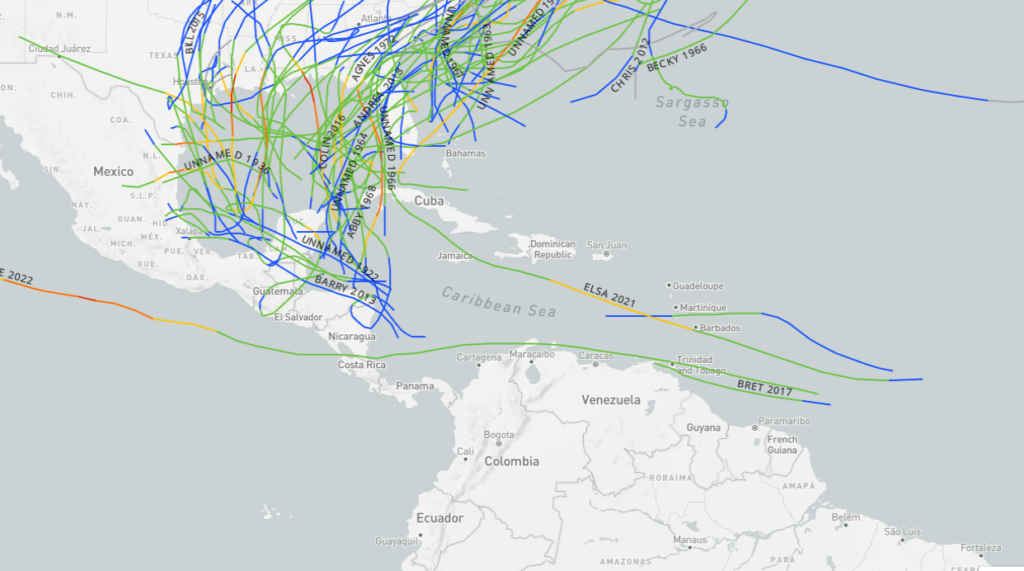

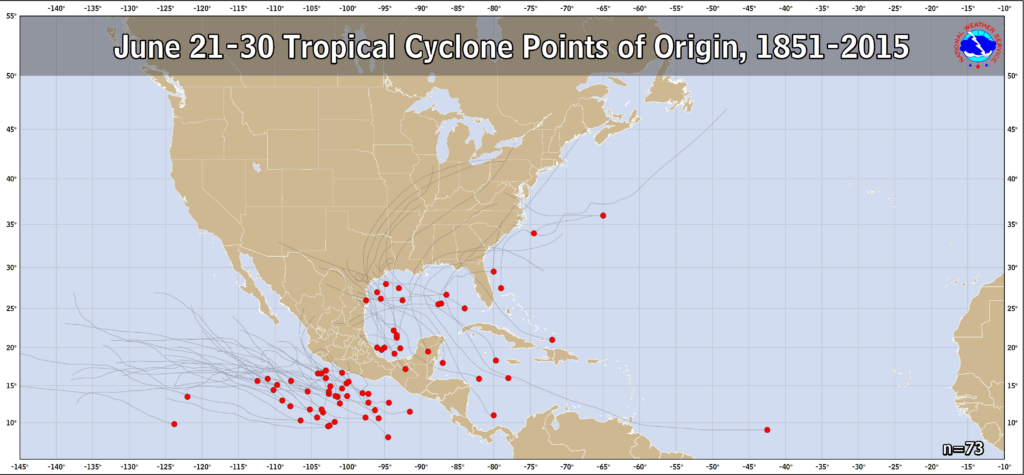

If you look at a map of where June storms form at the end of the month, historically, you are not really looking east of the islands.

Through 2015, there had been one that developed in the same general area we’ll watch next week. Since 2015, we have added three more, so we’re either getting better at identifying systems that far east or this is a new phenomenon.

None of these storms became particularly large, though Elsa did become a category 1 hurricane and caused over $1 billion in damage, becoming notable also for being the first hurricane in years to hit Barbados.

Editor’s Note: As of 8 AM ET, the National Hurricane Center designated this as an area to watch over the next week, with 20% odds of development.

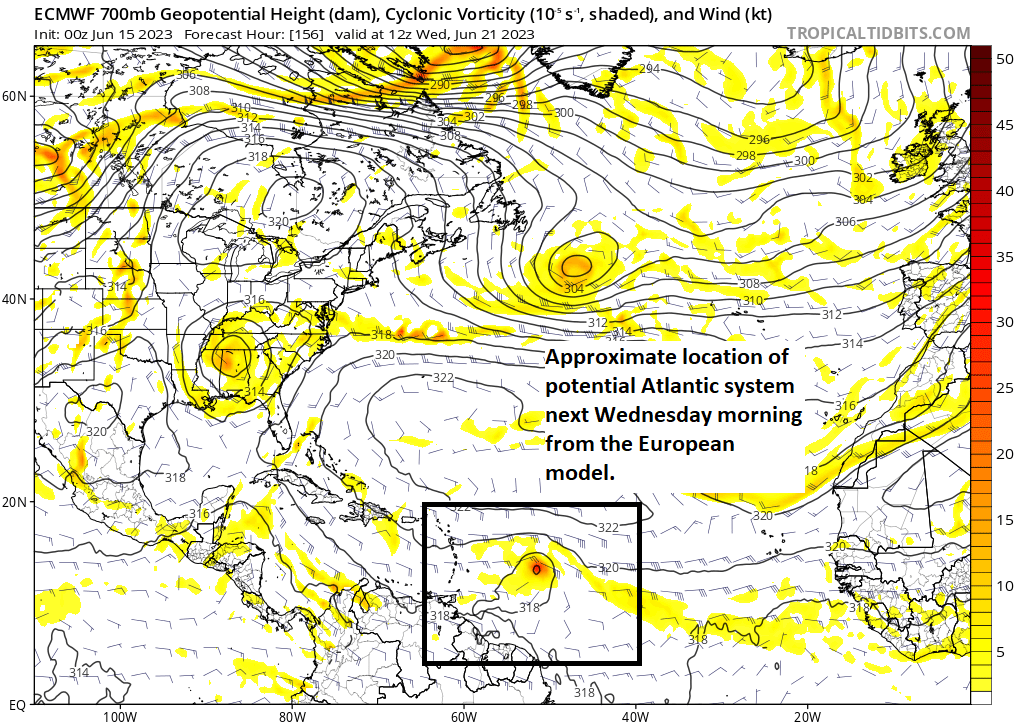

As we go into next week, that wave highlighted above near Africa will move into the Atlantic. Both the GFS and European models show it trying to develop, slowly, in between Africa and the Lesser Antilles. If we look at the European model in about 6 to 7 days, we can see a pretty clear signal about 10,000 feet up just east of the islands.

Interestingly, the GFS model has a similar situation shown. Ensemble guidance seems to validate this with a fairly weak ensemble mean signal and about 50 percent of individual ensemble members showing development. The maps shown here today are from deterministic, operational models, as they have a clearer signal we can highlight. But meteorologically, we are looking closer at the ensemble guidance, which gives us 30 to 50 different outcomes and allows us to blend together a more nuanced picture of development chances, which are elevated but by no means a lock.

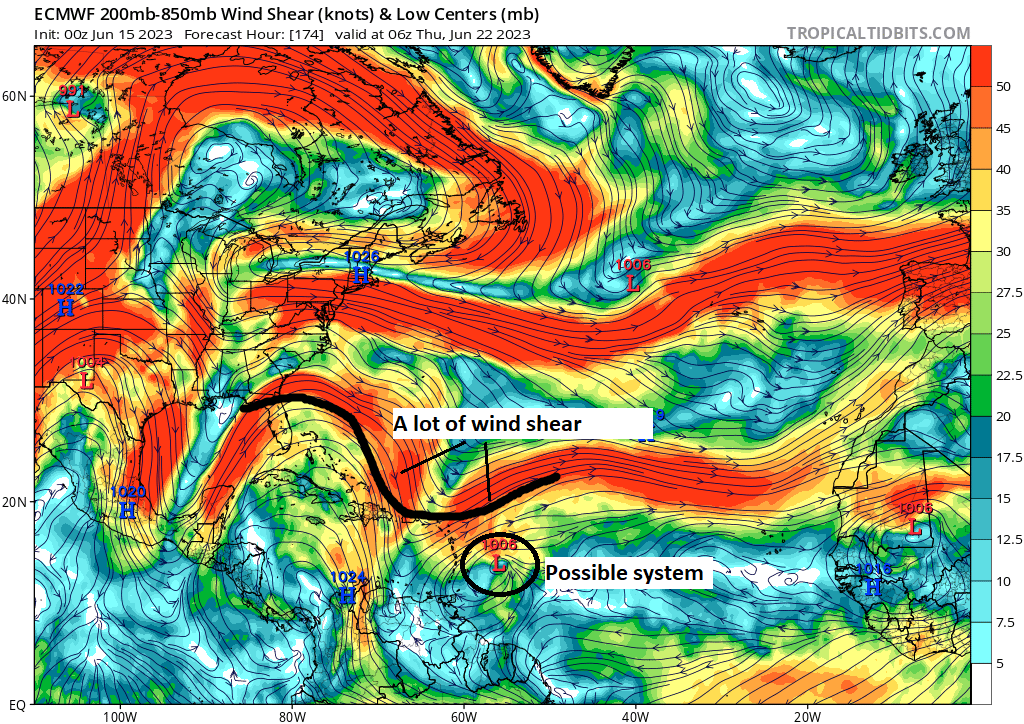

So what to make of this if you live in the islands? Well, you should monitor this. I think there’s enough signal on the models right now that makes it clear that, at the least, some sort of robust disturbance is going to approach later next week. It may not organize, it may turn before getting there, or it may come through as a tropical system. We just don’t know at this point. Would it be a big storm? Probably not, given the time of year, dust in the area, and some (a lot of?) wind shear as well.

So, if you live in the Lesser Antilles or Virgin Islands or Puerto Rico, this is worth monitoring but probably not worth getting too worked up about. It’s a definite oddball given where it could develop relative to the calendar. But it seems likely that it will have some hurdles to face to become a defined tropical entity. We’ll keep watching and have more tomorrow.

Fantasyland (beyond day 10): Still noisy, still not super impressed

The Atlantic system will probably disperse at some point in this timeframe, so we could see unsettled weather in the Caribbean. We are continuing to watch the western Caribbean for some noisier conditions but we remain unimpressed with the odds of any organized development in this timeframe.

Yesterday was great. Please keep up the good work.

Thank you!

Super creepy that something’s trying to develop off Africa this time of year…

😮

Love that one sentence summary!!

In reference to your in depth piece yesterday, since comments closed on it and couldn’t comment yesterday.

I do appreciate that this piece is more balanced on the climate change debate. My question is though, how do you get around the lack of resolution with data for a 100 years back. Other meteorologist have been calling for this intensification during landfalling storms to occur for several years now, and they will site it occurred back in the 40s through 60s, which I assume correlates with the AMO. I think back to Hurricane Michael which hit an area which wasn’t densely populated, if the same area was hit 100 years ago in Florida…..while I am sure we would have known a strong storm went through, would we even have enough data to differentiate between a Category 3, 4 or 5 based on damage to natural features? Granted, I am not an expert by any means, but the damage along I-10 to the forests from Ivan and Michael (I’ve driven this route too many times in my life over the past 20 years) looked very similar to me. I guess storm surge inundation might be another method, though we saw with Katrina that there is a bit of a lag effect and overall area coverage of the storm is a huge influence. Even today we have categorized numerous storms as Cat 5 in post-analysis (I believe Andrew and Michael come to mind). I also think about Harvey vs Claudette in 79, I could be wrong, but my guess would be we have a lot more rain gauges across the Houston metro area during Harvey than Claudette that maybe somewhere actually got more rain than Alvin even?

My apologies if this is a elementary question, but it seems we have really limited time frame of really good data in which we are trying to infer abnormalities from natural variations.

Hi ASH, you hit on a topic that’s one of the bigger challenges some of this research faces but I don’t know that it’s as big a challenge as it seems. As tempting as it is to assume we missed intensification events of the past, it’s unlikely that a material amount are missing. In fact, studies that focus on the so-called satellite era (1970s to present) seem to be mostly in line with what research says at a higher level. So, I wouldn’t assume too terribly much is off due to observational gaps. The active periods of the past in conjunction with the AMO are something that’s notable, but I think even the AMO is being called into question now as an adequate oscillation, even by the creator of it themselves. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6941994/?cf_history_state=%7B%22guid%22%3A%22C255D9FF78CD46CDA4F76812EA68C350%22%2C%22historyId%22%3A10%2C%22targetId%22%3A%22A8BB053824ACC7490320EC3D7F4C61C2%22%7D

Rainfall is indeed another matter, but it’s not as if the NWS didn’t have radar back then to help with rain in, say, Claudette. If you want to argue some storms in the 1900s-1950s may have some observations missed, that’s a fair argument to make. I think the reality is that, yes, the density of observations has improved considerably and aided in getting more data in the last 20-30 years versus 50-75 years ago. But the research outcomes may be immaterial in key areas. Hope this helps!