One-sentence summary

Today’s post goes in deep on this weekend’s winter storm in the East, previews next week’s potentially major storm in the Eastern half of the U.S., and discusses what stratospheric warming and the polar vortex actually means.

This weekend’s storm: Snow chances highest north and west of I-95

Back on Tuesday, we laid out the groundwork for this weekend’s storm. There’s been a lot of hype surrounding this, and we tried to cut through some of it to show that the highest odds of significant snow would be north and west of the I-95 corridor, with the exception of New England. So what has changed since?

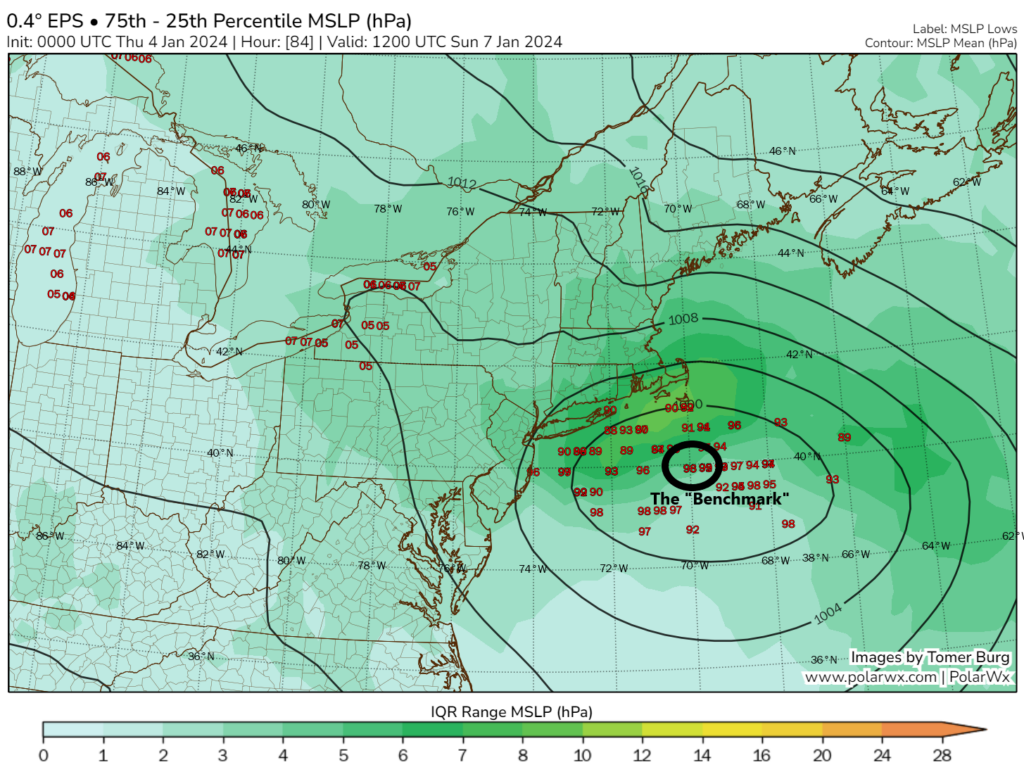

Not a whole lot. I love these IQR plots from Tomer Burg’s site. In simple terms they’re showing you the uncertainty within the modeling. When it comes to storms like this, you have to use ensemble guidance. Recall, the ensembles are 30 to 50 runs of a model with some tweaks each time, so you get a more realistic spread of possibilities. Often, when you’re watching the TV news or you see a loud post on social media, they’re showing you deterministic guidance, or what we often call the operational models. That’s the whole GFS vs. Euro thing you hear about sometimes.

But back to Tomer’s plot. On Tuesday, I noted “the European ensemble shows a number of storm tracks on either side of the Benchmark with several rather close to the coast. This means uncertainty is high.” Then, as a meteorologist, I looked to see what our cold air supply looked like, and it’s meager. All this to say that it made sense to think that snow would stay mostly north and west of the I-95 corridor, with the exception of New England, where the storm track may favor more snow. That’s a lengthy introduction to say, here we are today:

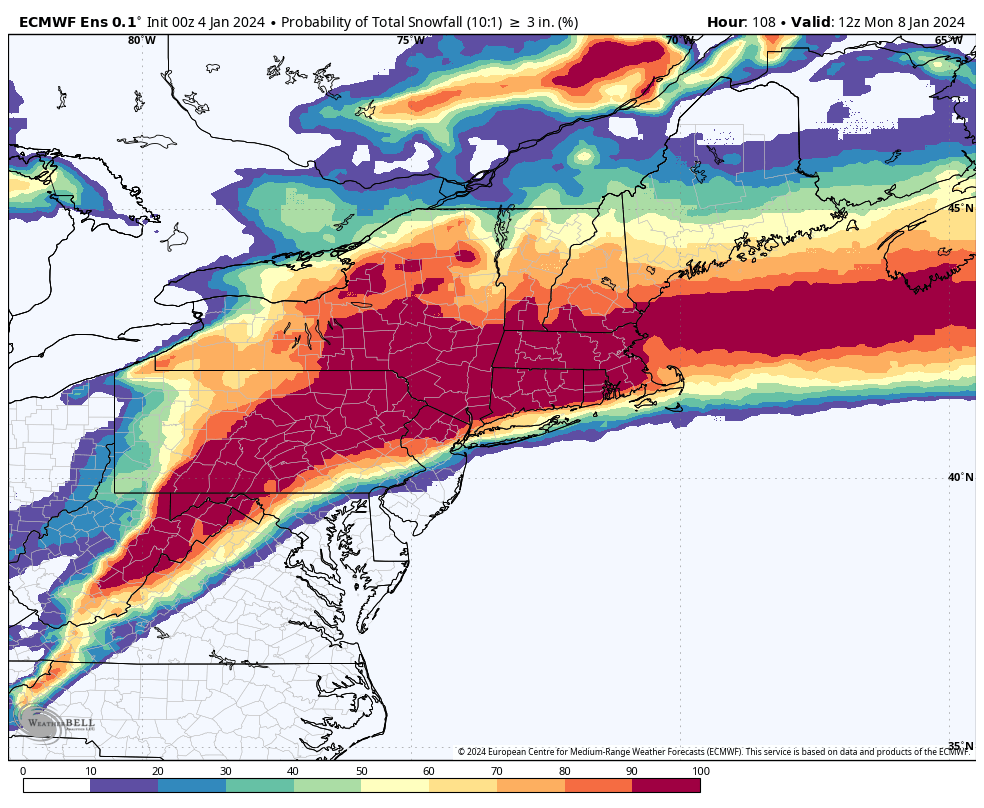

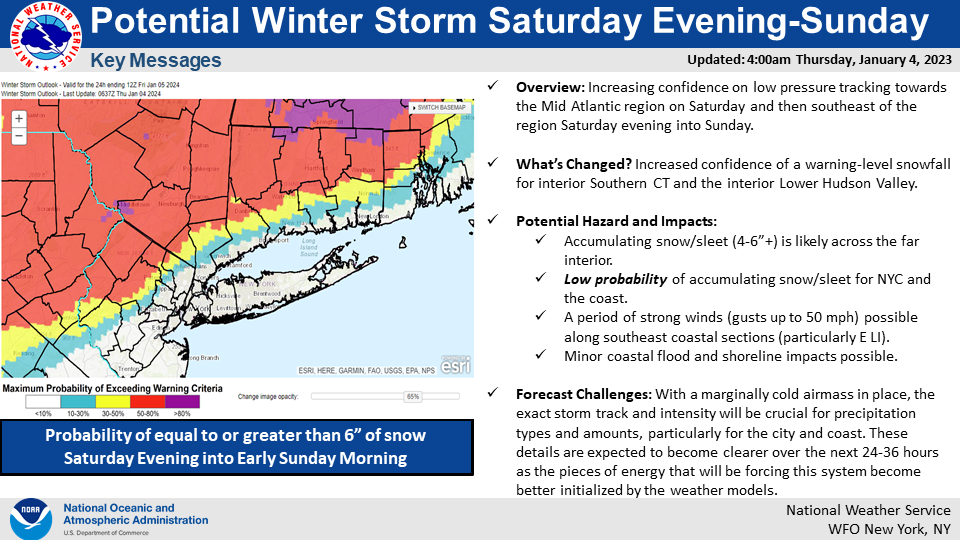

Since Tuesday, uncertainty has dropped, and we’re seeing a coalescing of ensemble members at or north and west of the 40/70 Benchmark. With this type of track and a distinct lack of much cold air, the focus of snow will likely be inland for this event, with rain or a mix at the coast. With track forecast confidence comes snow forecast confidence to a point. If we look at today’s odds of 3″ or more of snow from the European ensemble, here’s what we get:

Back on Tuesday, Washington, DC had about a 40 percent chance of 3″ or more snow. Today, that is less than 10 percent. For Philly, we were around 40 to 50 percent on Tuesday, and we’re down to about 20 to 30 percent today. New York City was 50 to 60 percent on Tuesday and may be about 75 percent today. Boston and most of Southern New England were 60 to 80 percent on Tuesday and near 100 percent today. So, over the last couple days, as the models have sort of nudged things north some, the snow cutoff has nudged with it, with lower odds in Philly and DC and higher odds in New England (as you might expect with the storm closer).

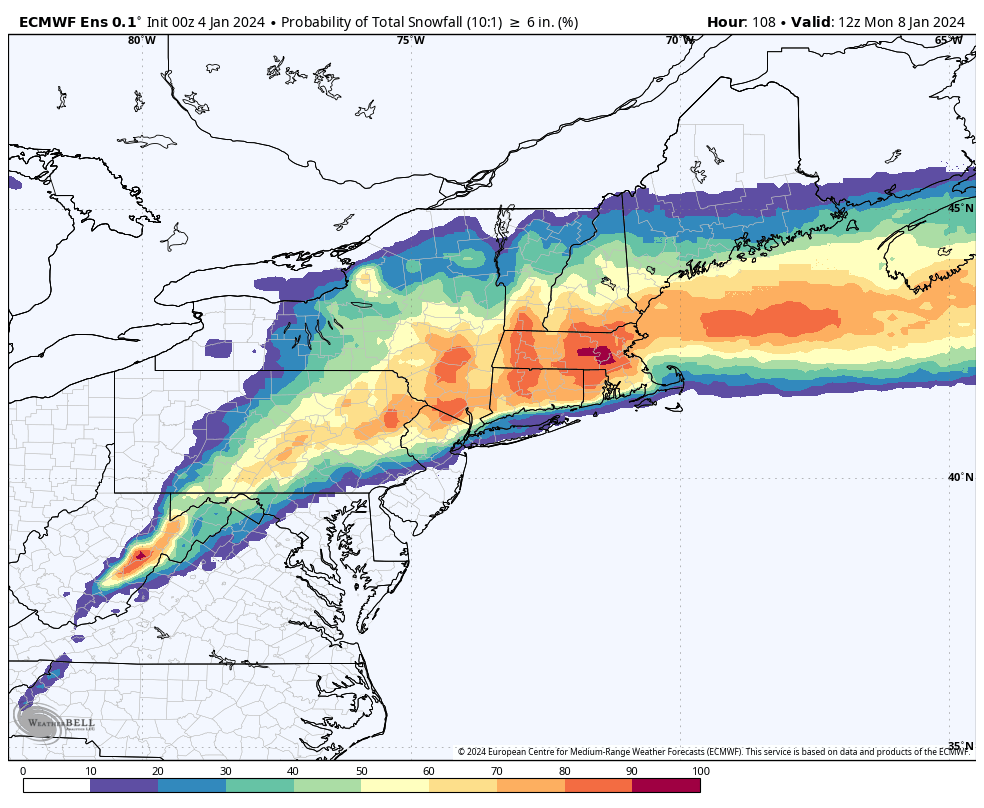

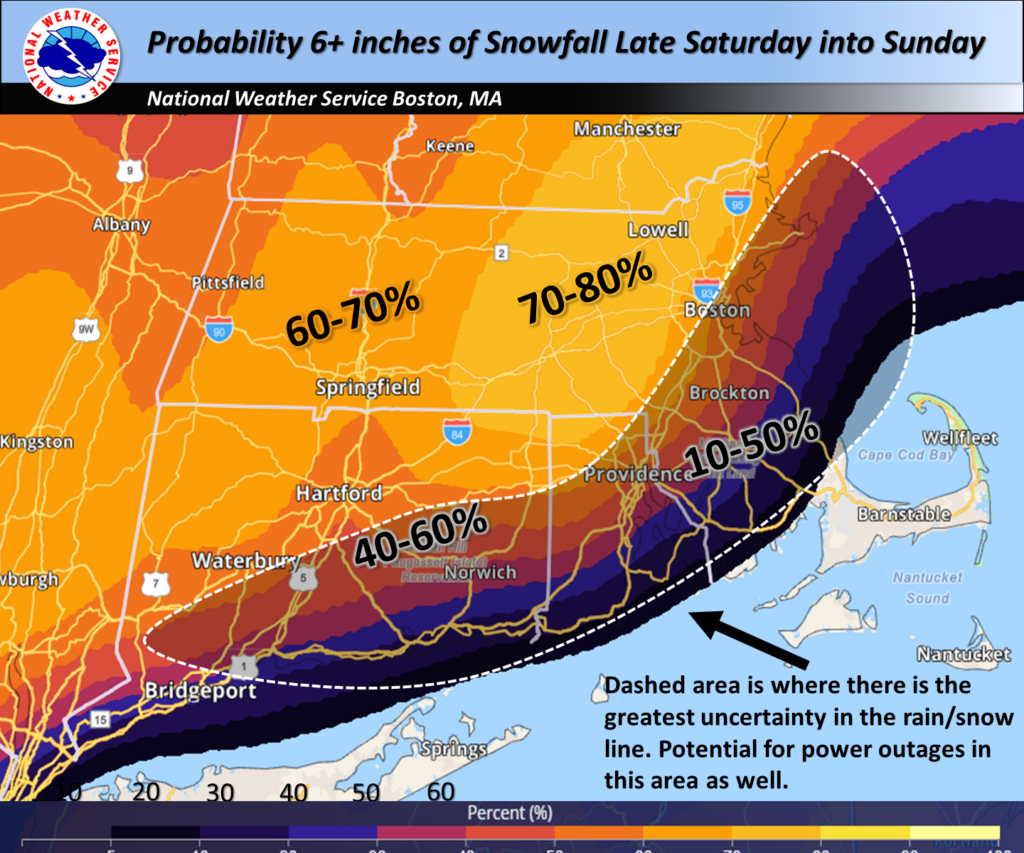

Let’s ratchet things up to 6 inches. What do those odds look like?

The 6 inch probabilities are interesting, and you can begin to see where the highest uncertainty may be. From Philly south through DC, the odds of 6″ of snow are extremely low, if not close to zero. This looks like a snow to rain or mix event there. My homeland of Southern New Jersey is in the same boat. Things get much trickier though once you get into areas north and west of Philly up into New York. The “gradient” of snow percentages increases dramatically over a short distance. For example, you have about a 10 to 20 percent chance of 6″ of snow on Staten Island but about a 50 percent chance in the Bronx. Similar style gradients exist in North Jersey and near coastal New England. That’s according to the European model. In reality, with cold air lacking, I think these odds may even be a bit too high on the southern end, and I am going to assume that most of NYC will see some wet snow to a mix or rain. The NWS in New York City highlights the chance of interior snow, with a very low chance that the city sees accumulating snow.

For New England, the battle line becomes the coast, with the typical problem areas from a forecasting perspective coming to fruition this time as well. Despite the cheery view of the Euro in Boston, the actual odds are probably a bit less than shown for 6″ or more snow there, and the NWS Boston image below shows this, with about a 50 to 60 percent chance for the city.

All in all, we’re likely looking at a storm with the greatest odds of meaningful snow from portions of interior Pennsylvania through northwest New Jersey, the Catskills, Litchfield Hills, perhaps to Hartford and Worcester, southern Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. For the northwest suburbs of NYC and for Boston, it will be a closer call.

Don’t overlook the wind and coastal impacts with this storm either. A pretty healthy period of wind is possible from about Long Beach Island, NJ up through Long Island and coastal southern New England. This will likely cause some minor coastal flooding and possible beach erosion as well.

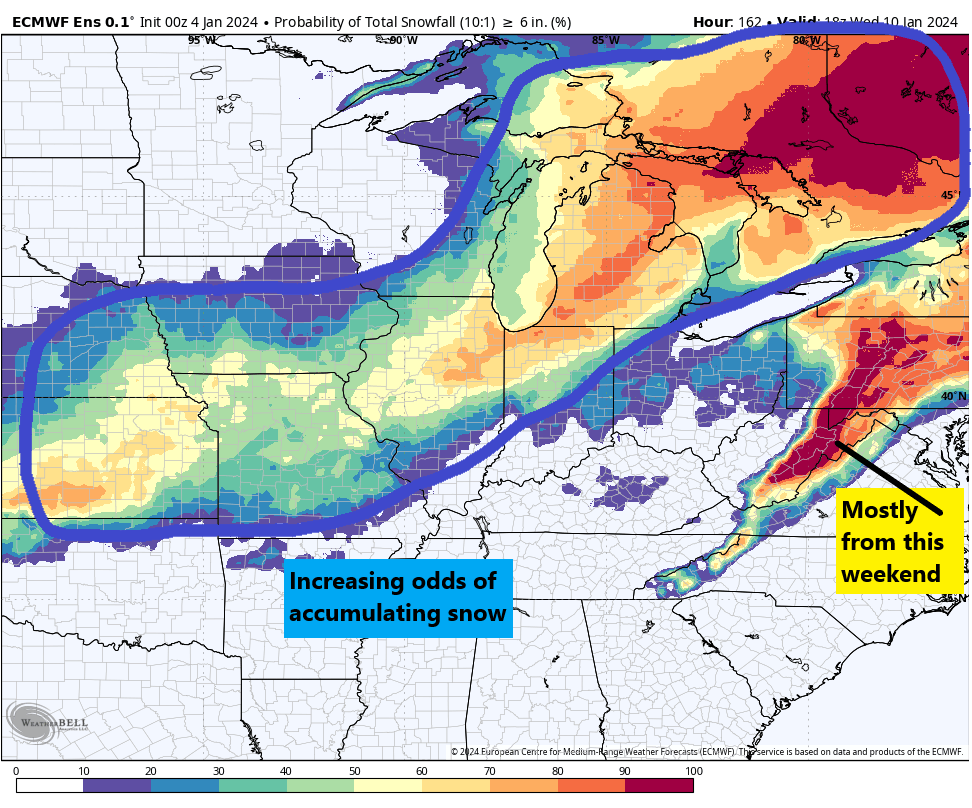

Next week: A major interior U.S. winter storm with big wind possible

It’s still a bit too soon to get into the finer details, but we are likely to see a much more significant storm next week across the interior U.S. Modeling has been consistently indicating the odds of a deep, strong area of low pressure tracking from Texas into the Ohio Valley and Ontario and Quebec. This storm is going to have it all: Heavy rain, severe weather, heavy snow, and powerful winds. Here’s a quick overview of what we’ll be watching.

Heavy rain: A swath of heavy rainfall is likely on the warmer, Eastern side of this storm from the Gulf Coast up through the interior Southeast, Mid-Atlantic, and possibly the Northeast. The Weather Prediction Center already has a slight risk on day 5 (Monday) for the central Gulf Coast, which is level 2 of 3 at this timeframe.

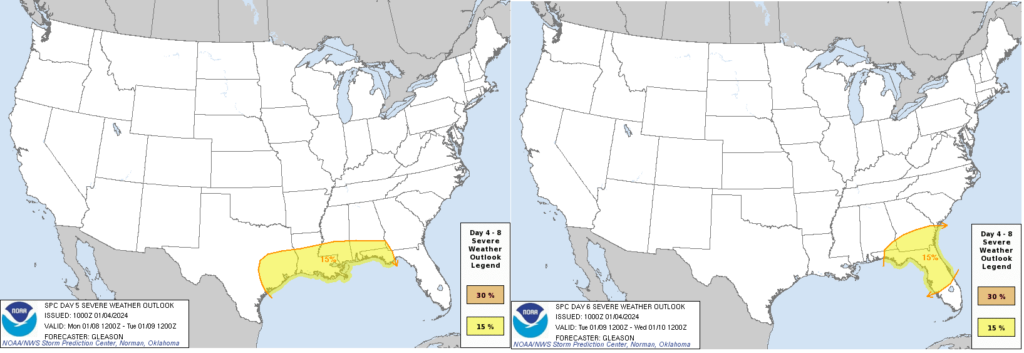

Severe weather: The Storm Prediction Center is highlighting the chance for severe weather on Monday from Texas to the Florida Panhandle and on Tuesday in Florida and Georgia.

It’s too early to speculate on details, but just know that severe weather is a possibility early next week.

Heavy snow: There is an increasing chance of heavy snow for somewhere between Kansas and Missouri into Iowa, Illinois, perhaps Indiana, Michigan, Ontario, and Quebec. Current European ensemble model odds of 6″ or more snow are relatively high in Kansas, Illinois, northwest Indiana, and Michigan into Canada.

It’s far too early to speculate on details, but it’s apparent that someone will get a good bit of snow from this storm. One of the challenges again in this storm is a lack of cold air. There will be significant cold dumping into the Western US, but the Plains and Midwest have decidedly blah cold air available at this time. A lot of time to sort this out still.

Strong winds: In my opinion, the heavy rain in the East and the strong potential winds from this storm are the most serious looking elements next week. Modeling is at least implying the risk of a wide area of 30 to 40 mph or higher winds from the southern Plains into the Southeast, Ohio Valley, East Coast, and Great Lakes. Expect this storyline to become more noteworthy in coming days as the details of this storm get sorted out.

Is the polar vortex coming?

I want to close by addressing something that’s got a lot of people spooked or excited or more aware than usual of winter weather. There has been a lot of speculation on social media about the polar vortex coming later this month. The reasoning is attributed to a sudden stratospheric warming event (SSW) that displaces the polar vortex from the Pole and dumps cold air into the mid-latitudes where most people live. It sounds pretty terrible, unless of course you love cold. So what’s the deal, really?

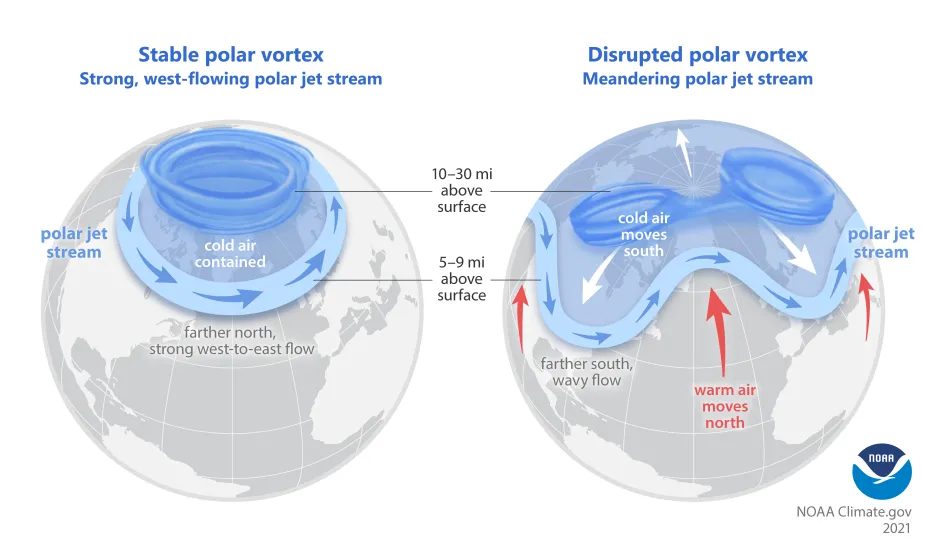

Every winter, the polar vortex strengthens over the North Pole. It basically houses the coldest air in the Northern Hemisphere. It’s never perfectly still, but it’s usually confined to the North Pole. Every so often, the polar vortex can be disrupted, allowing cold to leak out of the polar region and toward the mid-latitudes, where most people live.

The image above lays out, broadly how this happens. For example, this winter has been a mild one for most of the U.S. so far, and it’s not a shock that the polar vortex has been fairly strong.

One of the pathways to displace or split the polar vortex is by what we call a sudden stratospheric warming. What is that, and why does it matter? When we talk about the “polar vortex,” most meteorologists are actually referring to the stratospheric polar vortex. We’re looking about 10 miles and higher up in the atmosphere. That’s the actual polar vortex. When you think of the polar vortex, you’re likely thinking of blobs of intense cold that periodically drop into the U.S. during winter. So, they’re two fundamentally different things. Related, but different.

During some winters, there will be a disruption of the stability in the stratosphere that happens via a sudden warming event, where the strong westerly winds locking the polar vortex over the Pole can weaken or even reverse. When that happens it can release some of that cold from the polar region into the mid-latitudes, impacting the U.S. or Europe or Asia.

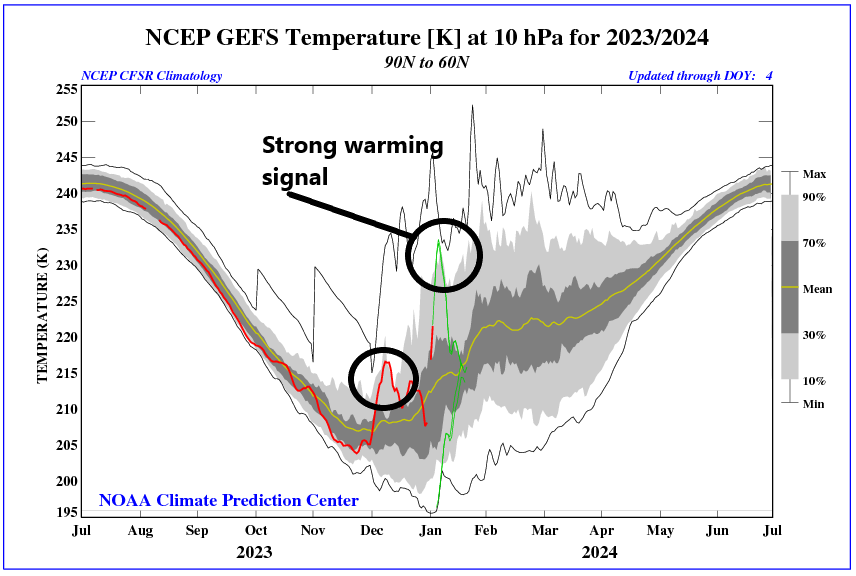

But that’s not a guarantee. No two SSWs are identical, and not every SSW will lead to a “release the hounds” cold air outbreak over the U.S. (or Europe or Asia). There’s a lot that we don’t completely understand about these events and what causes one to produce big cold or another to do little to nothing. But the bottom line here is that this year we are seeing a minor SSW event ongoing. This will do some work on the polar vortex, and it should allow for a relatively wavier jet stream heading into later January. That does not mean a repeat of the February 2021 or December 2022 cold events in Texas, but it could mean some pushes of stronger cold than we’ve seen so far this winter.

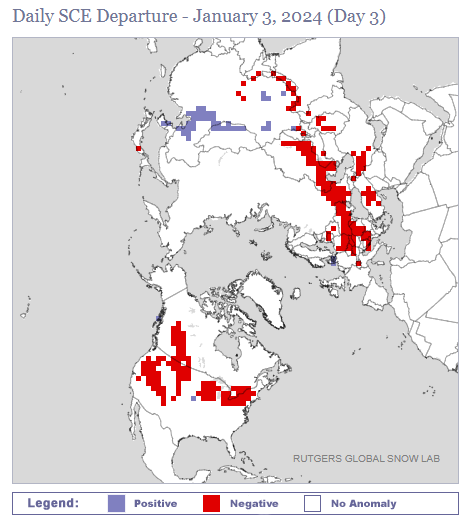

One hurdle right now is that snowfall across North America is running a good bit below normal.

Snow cover is below average in the West, Canada, the Midwest, and Plains. Cold air modifies and moderates as it comes south, and when it travels over less snowy ground, it can moderate faster. This can change in the coming weeks, but will it happen in the Plains? That’s TBD.

The takeaway from all this is that a SSW event does *not* guarantee strong cold air. There are complicating factors involved that can prevent strong cold from materializing. However, an SSW event does tend to weaken the polar vortex and increase the odds that colder air could emerge from the polar regions at times in a few weeks. That does not necessarily mean a repeat of February 2021 (Uri). These types of situations occur several times a decade and most do not produce historic cold air like we saw in that event. But they can produce some of the coldest air of a given winter. So our advice: Sell the hype. But don’t be surprised if the forecast later this month turns a bit colder than we’ve seen so far this winter.

thank you for doing this – it is not only educational – but fun to read

Thank you!

Excellent update!

Thank you!

Thank you for the update and great explanations. Always am learning something new. I am curious if the current SSW that we are experiencing is possibly related to the intense solar flare that happened on Dec 31, 2023?

Thank you, Susan! That’s unlikely. These types of things happen during both active and inactive solar periods. Perhaps there is a distant connection somehow, but if there is, we have not discovered it as of yet.

This is great stuff! Thanks!

Having grown up in Baltimore, I can attest that forecasts of snow in that area were always very tricky. Naturally, the school-age folks rooted” for snow to get a day or more off, but the parents of same, not so much – they had to drive in the stuff, and rear-wheel drive cars of that era didn’t do so well, even with “snow tires” installed.

Entertaining AND educational read.. thx for keeping this Wx fan in the know. Go RU!

Go RU! 🙂

OK, completely off topic but KPRC (channel 2 Houston) has been posting about the upcoming “hurricane season from hell” in 2024. Could we possibly have a non-alarmist post about this? How many grains of truth are in this? Is this going to be a season like 2005? Should we prepare for the next Hurricane Harvey? Do we REALLY know yet?

I’m not touching that. I know that they usually talk with a gentleman that has a method he uses and that they’ve found use from. I can’t honestly speak to how consistently good or bad it is, but that individual seems to think they’re on to something. Whatever the case, I would not worry about next hurricane season just yet.

Many thanks for this post. I’m in the mid-Atlantic region, with family in the Midwest, so a solid, non-dramatic, science-based discussion is greatly appreciated.