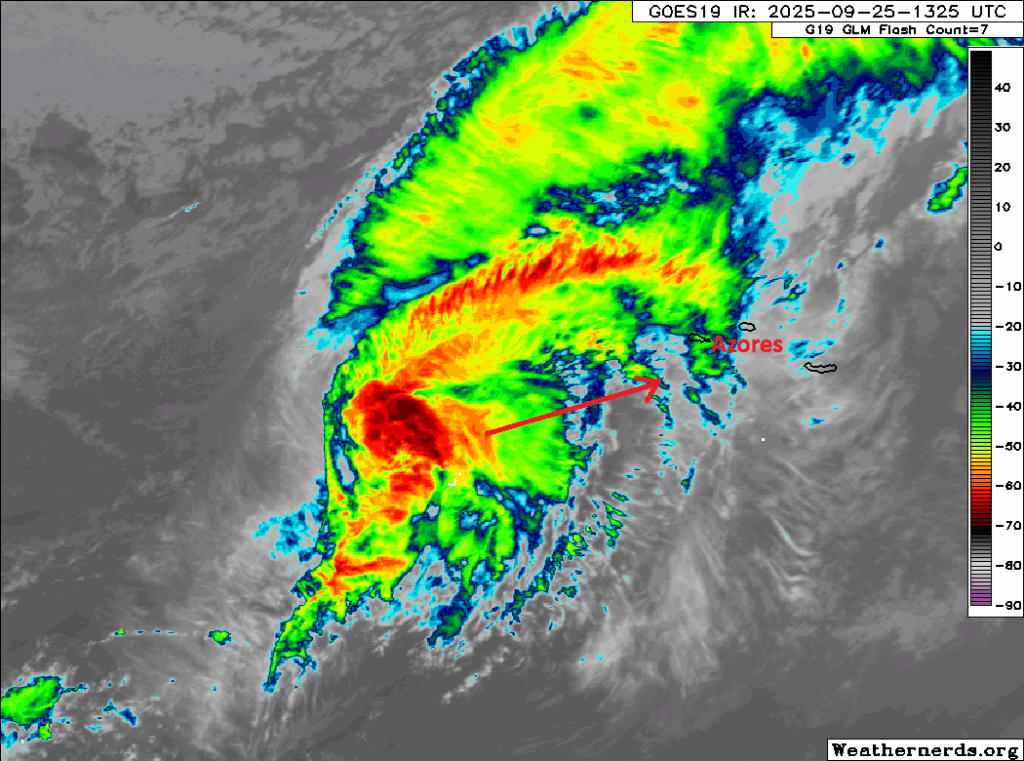

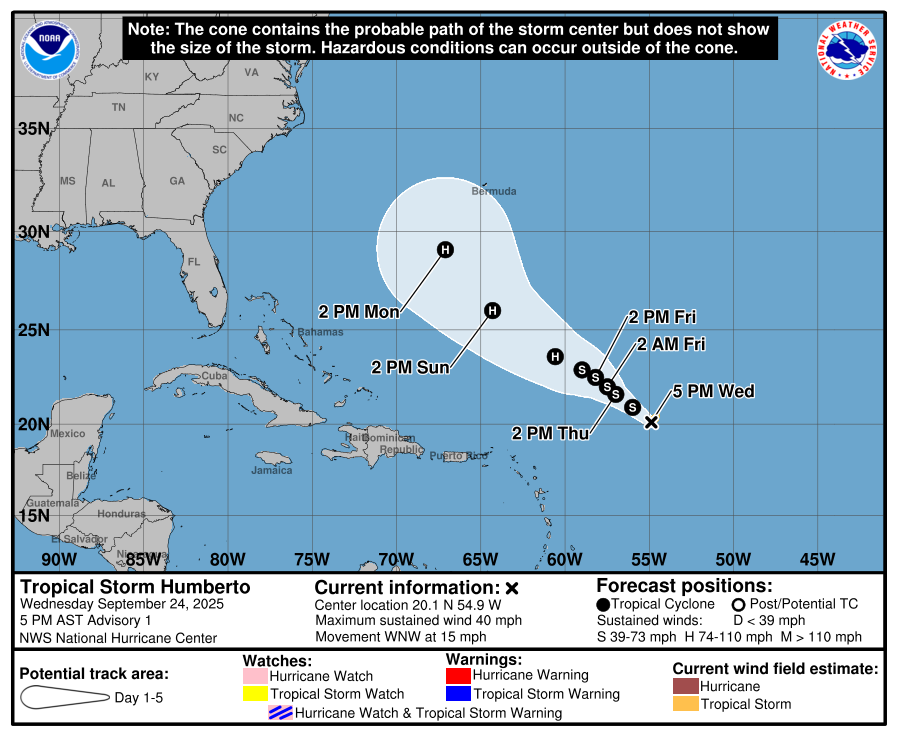

In brief: Invest 94L was reclassified as Potential Tropical Cyclone 9, meaning it is likely to become a tropical storm within the next 24 to 36 hours and produce tropical storm conditions in the Bahamas. We discuss the rain risks there and in Cuba. We also take a closer look at the current forecast goalposts of rainfall for coastal South and North Carolina.

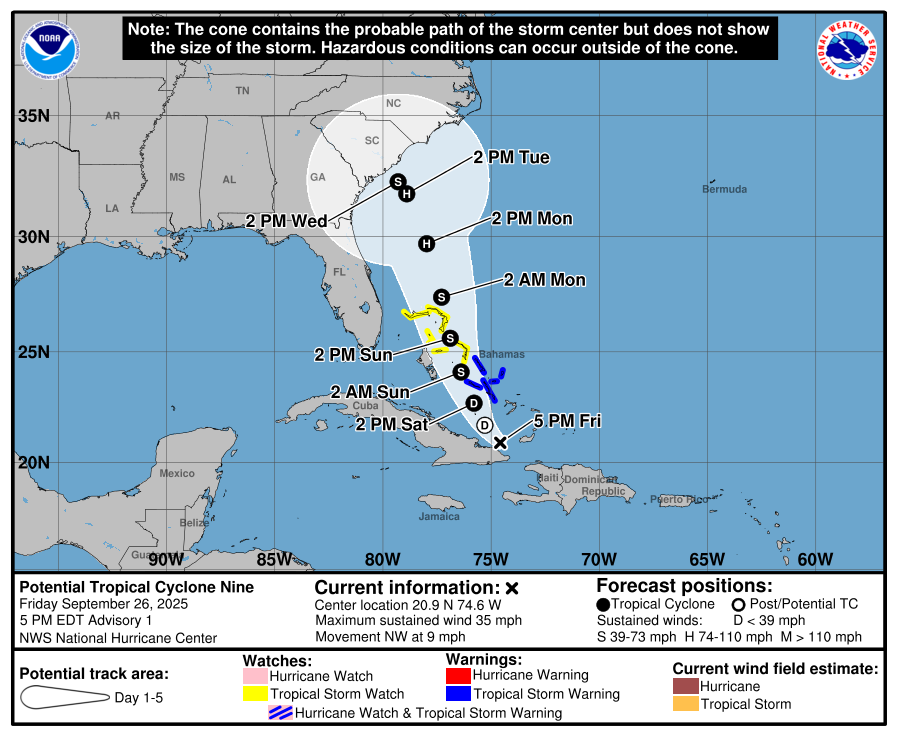

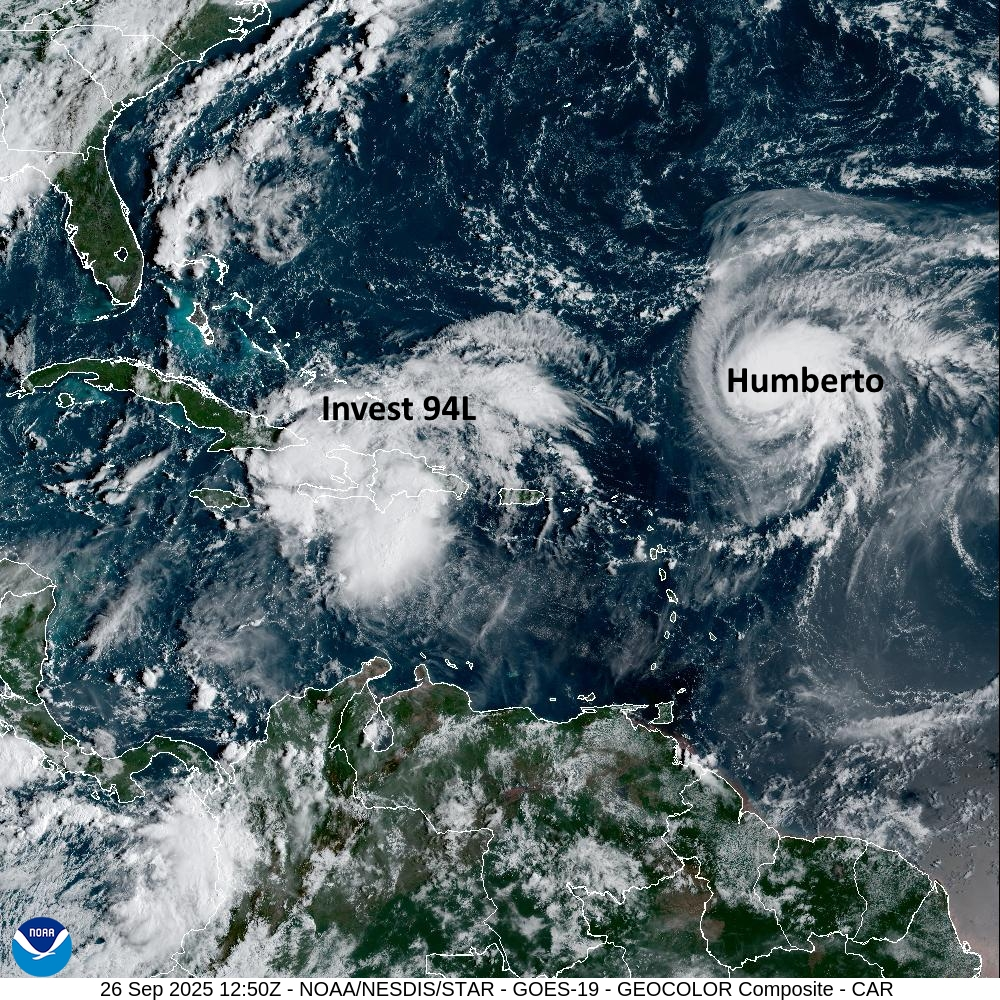

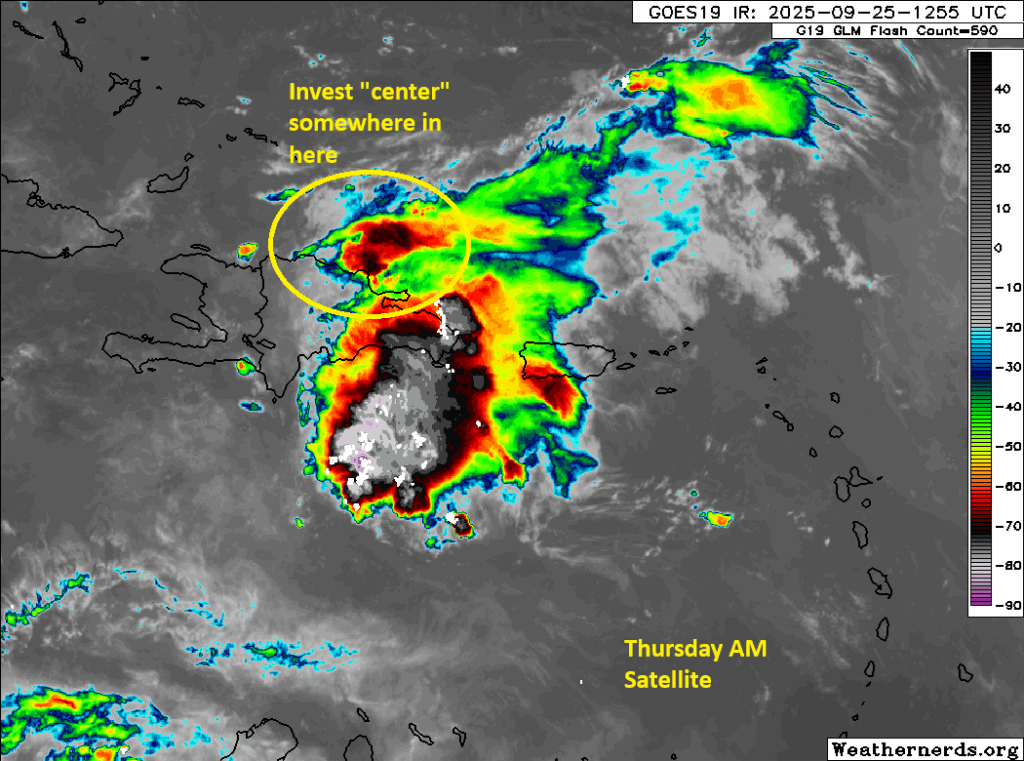

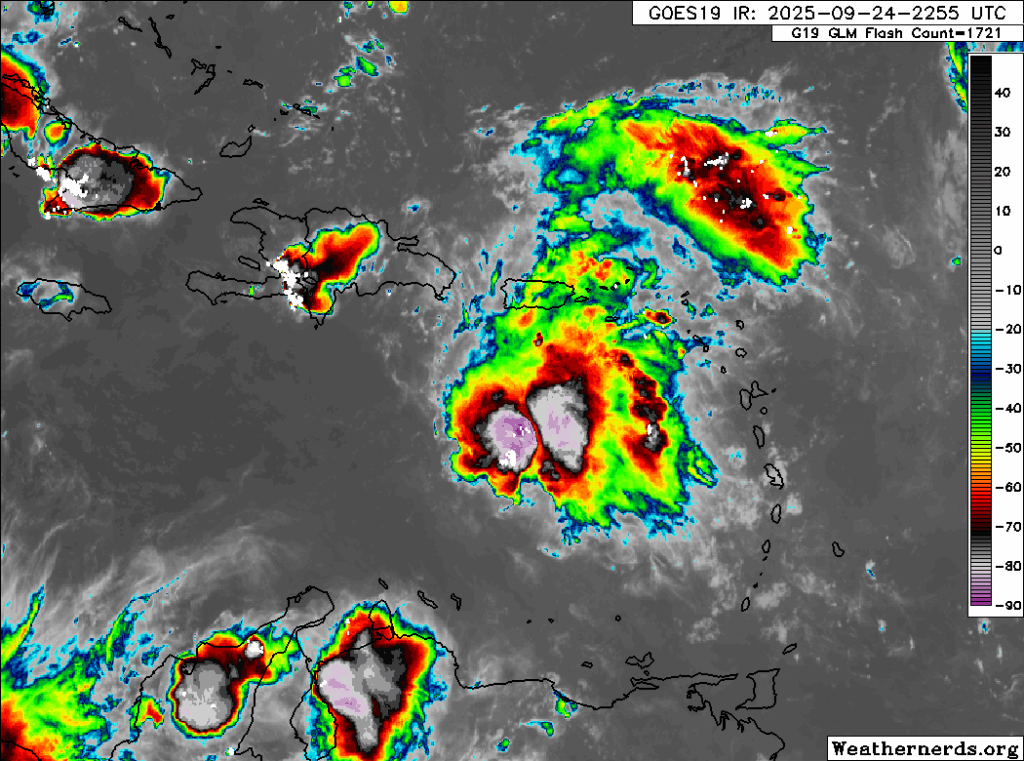

We wanted to add a post this evening to highlight that Invest 94L has been designated as Potential Tropical Cyclone 9, meaning that the National Hurricane Center expects it to develop within the next 36 to 48 hours, requiring tropical storm watches and warnings. In this case, those warnings are presently limited to the Bahamas.

PTC 9 is expected to become a tropical depression tomorrow and a tropical storm tomorrow night as it moves into the Bahamas. Heavy rain is likely in the Bahamas, along with increasing winds and seas as the storm moves through.

Some intense rain is likely over the eastern tip of Cuba as well. Rain totals may reach as high as 16″ or more in the higher terrain there leading to dangerous flooding and landslide risks.

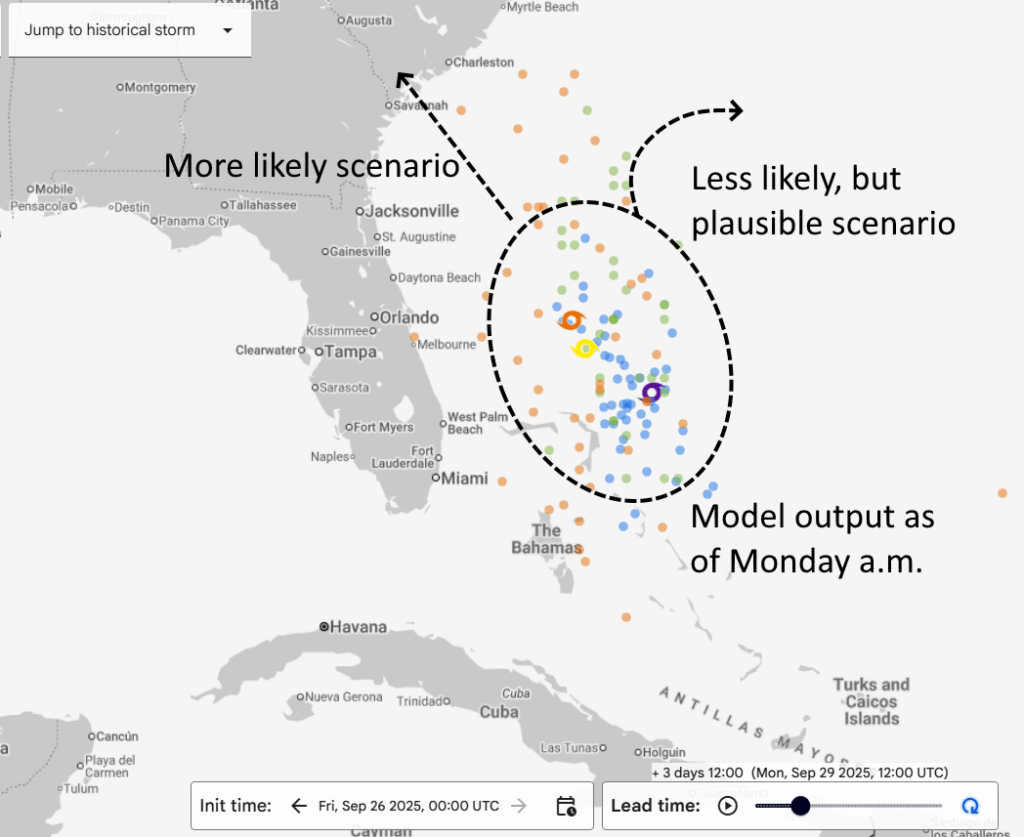

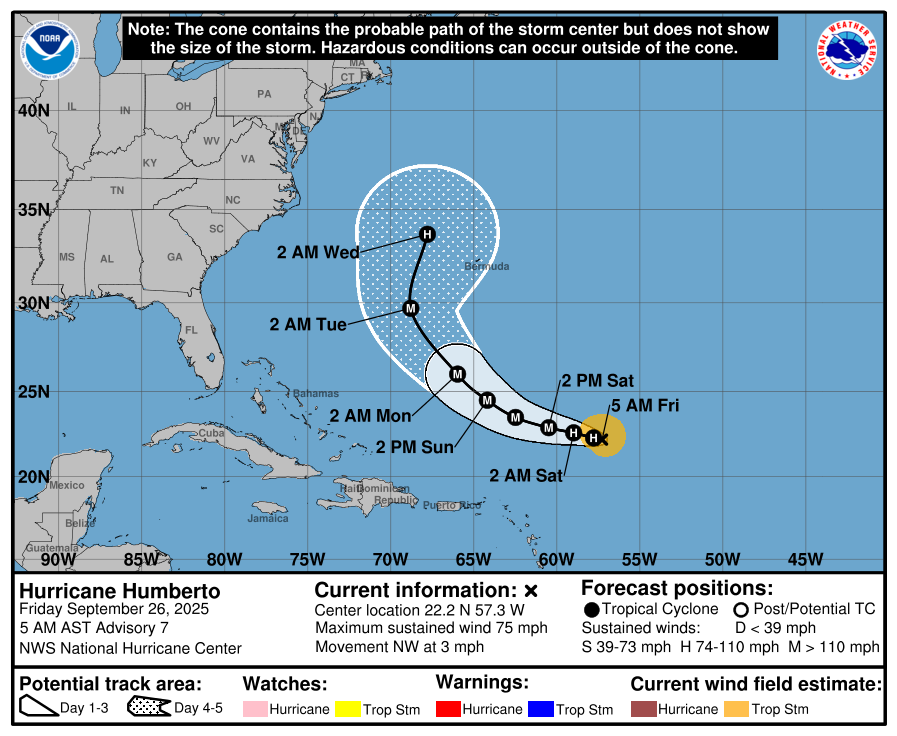

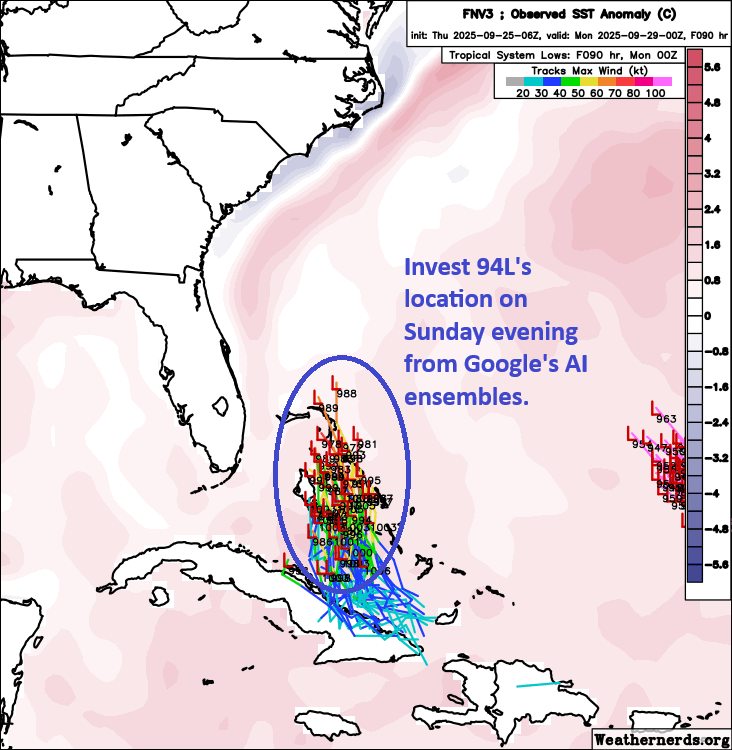

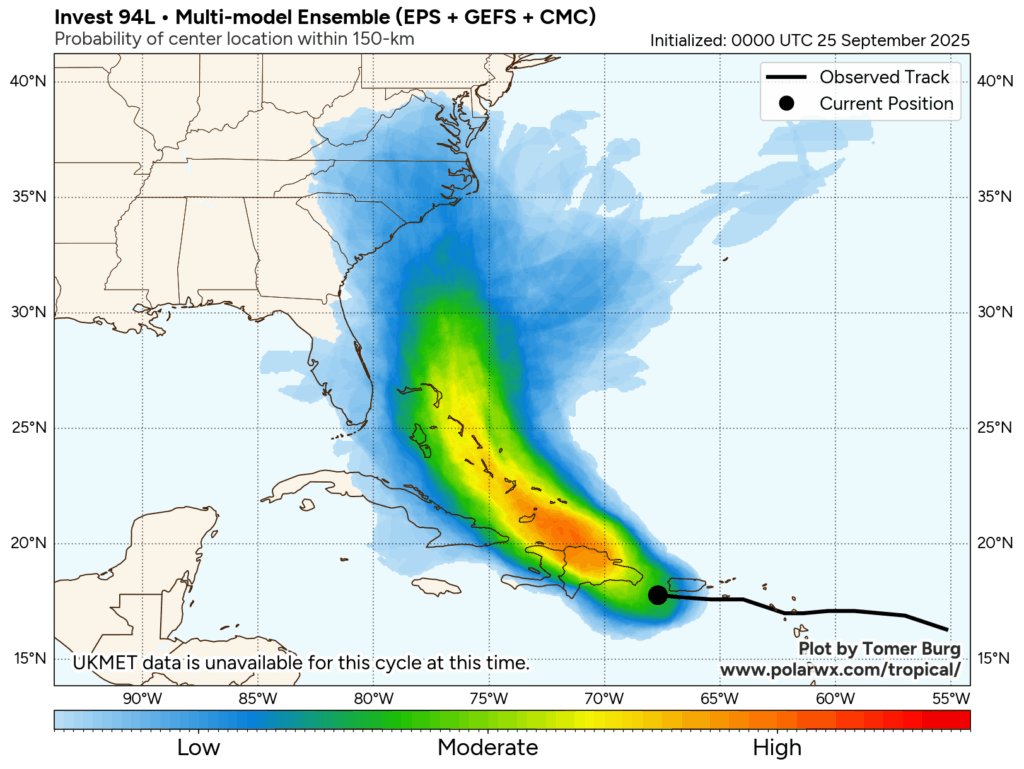

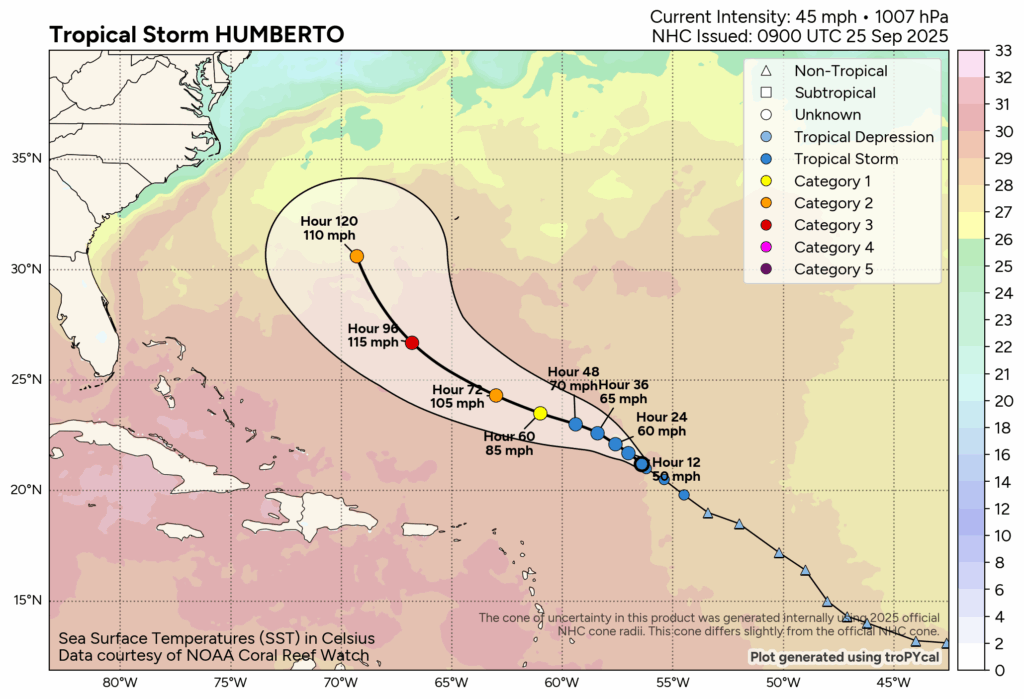

From there, you can see the National Hurricane Center track above. It shows a hurricane and eventually a tropical storm approaching the coast of South Carolina by Tuesday night or Wednesday. There is a tremendous amount of uncertainty on exactly where this system will go, and if you look under the hood and read the NHC’s discussion, they make this clear as well. It’s possible that a landfalling hurricane or tropical storm hits the South Carolina or North Carolina coast early to mid-next week. It’s also possible that this thing just taps the brakes and meanders offshore for a few days. Both scenarios deliver impacts, including torrential rain to the Carolinas, particularly in the Coastal Plain between the Lowcountry, Pee Dee and southeastern North Carolina.

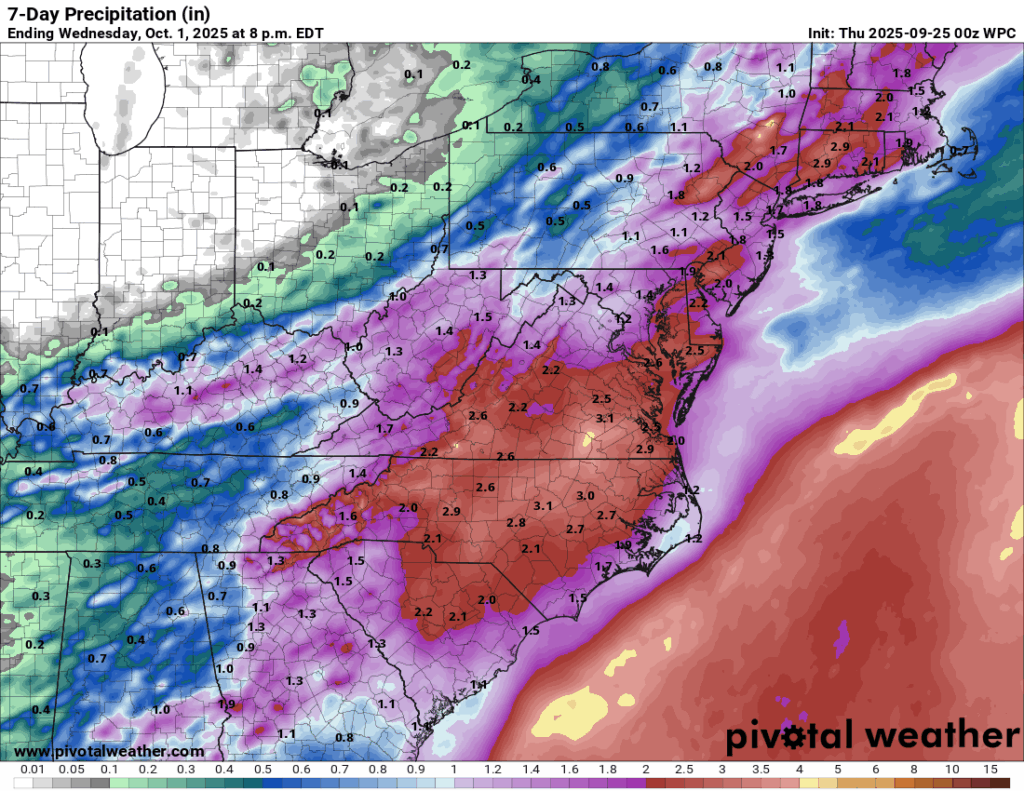

Rainfall scenarios

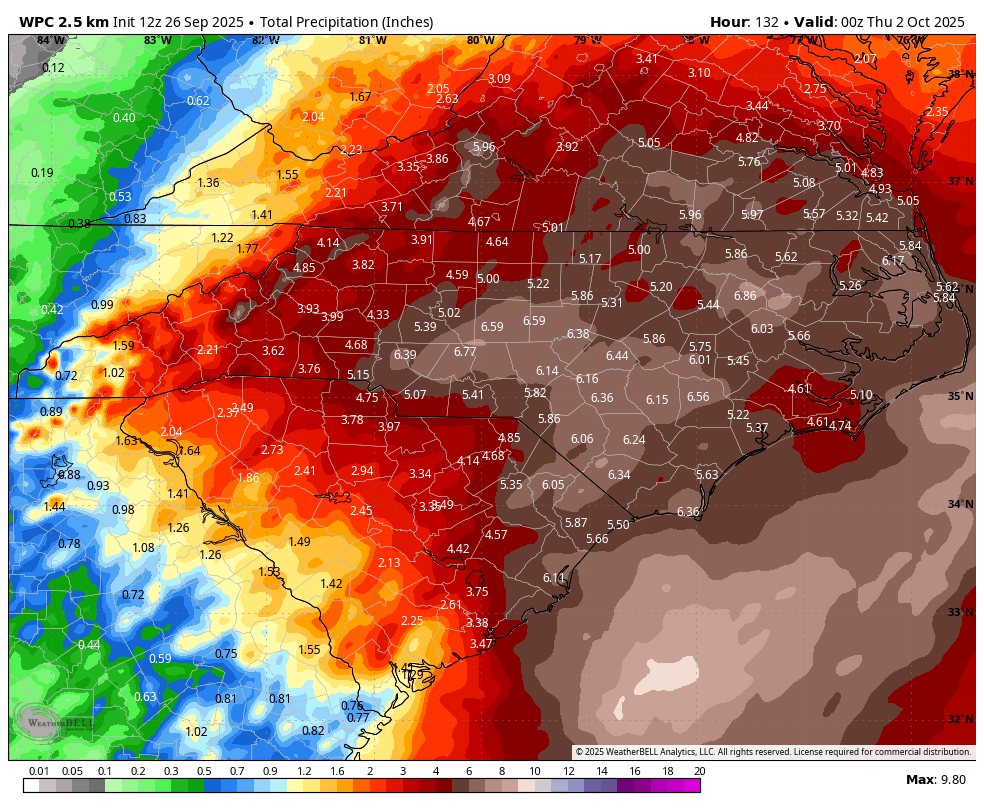

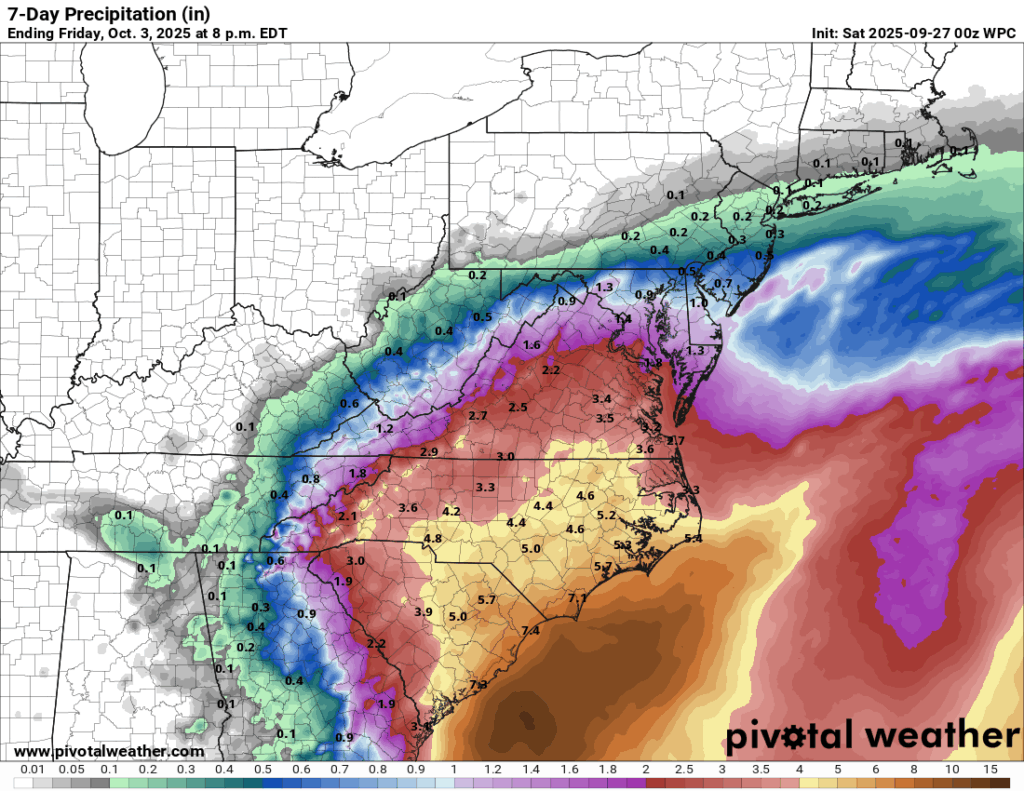

So let’s lay out a couple of the rainfall scenarios. First, here’s the current official forecast. Consider this the best estimate of how much rain may fall, on average, across the region over the next 7 days.

So, officially at least, the current thought is 4 to 8 inches with isolated higher amounts at the coast.

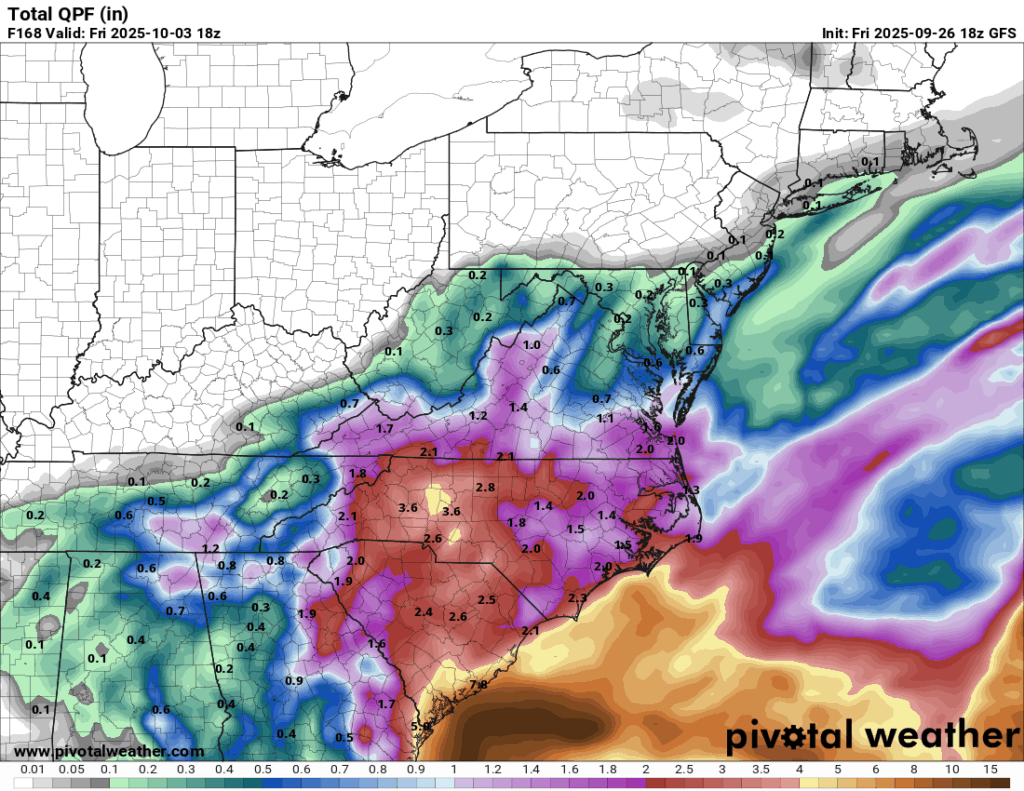

Let’s say the system never really makes landfall and approaches the coast but probably stays offshore and drifts eastward. The GFS model shows this fairly well today. Its rainfall totals are still impressive.

But they’re also notably lower than the current official forecast. This feels like a nice “floor” for how much rain could occur. I would anticipate at least this much. There will obviously be ways this could change, but given the scenarios in play, that’s where we are right now.

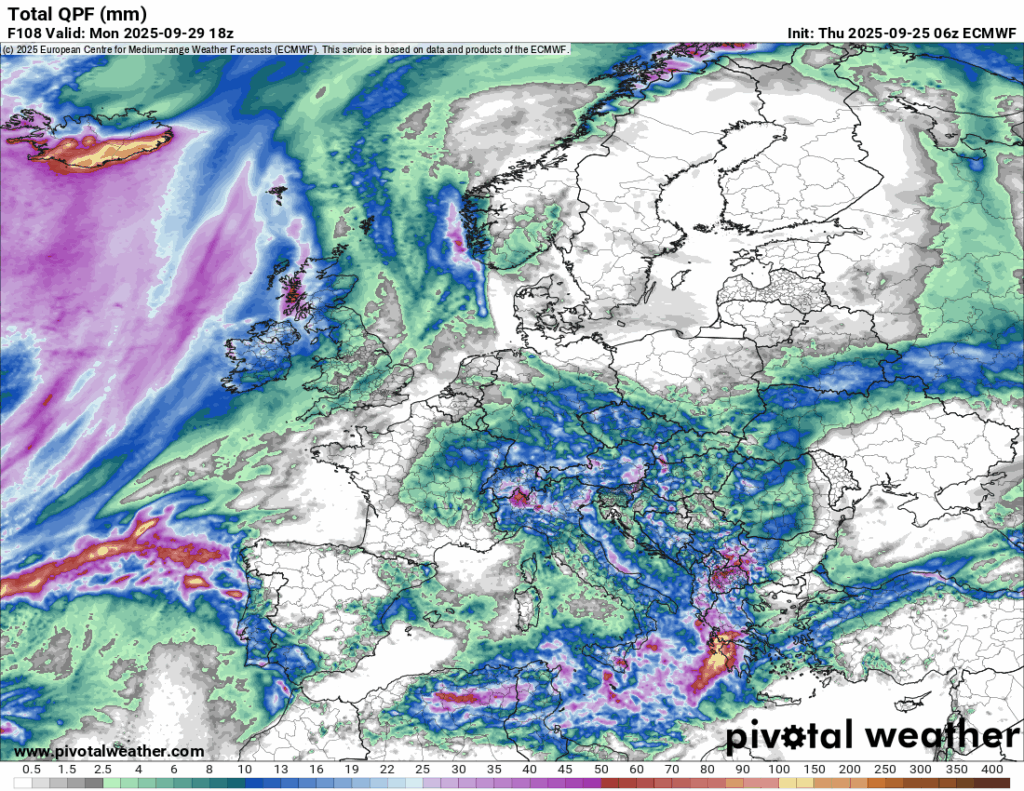

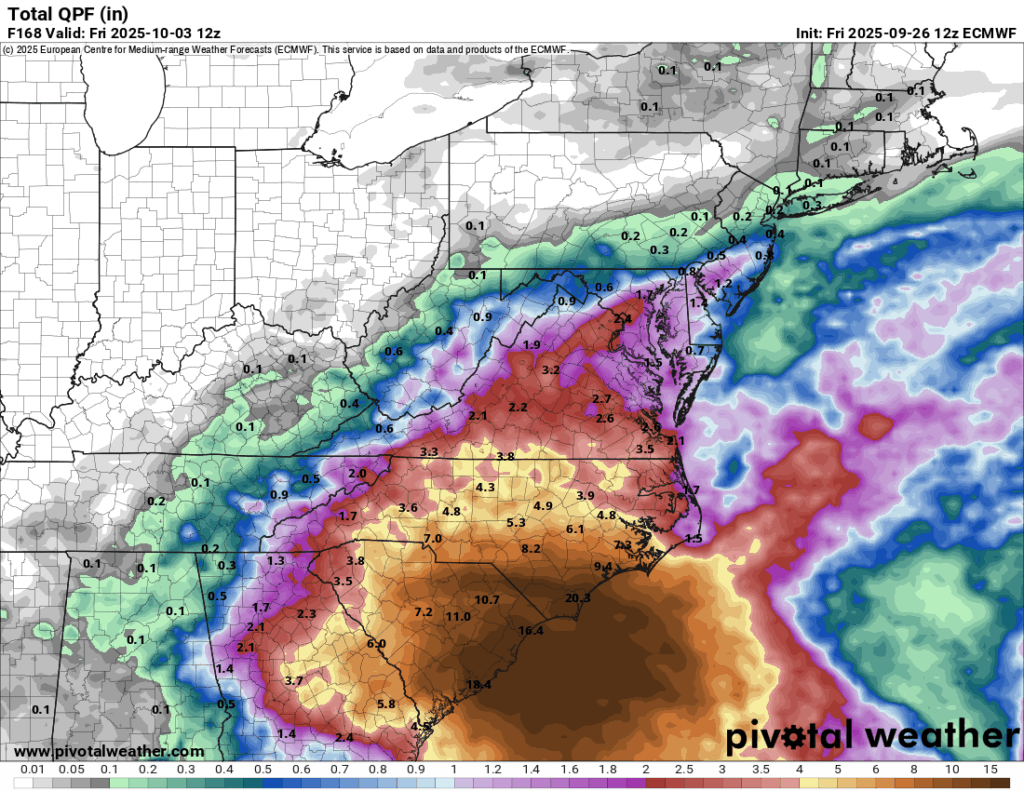

Now, let’s say the storm comes ashore or just hugs the immediate coast for a couple days. This is sort of what the European model showed this morning. How much rain falls in that scenario?

Well, the Euro represents an extreme example at the moment but one that cannot be entirely ruled out. In this scenario, rain totals of 20 inches would be possible on the coast between Charleston and Wilmington with a wide area of 5 to 15 inches in the Pee Dee and southeastern North Carolina. This would bear some similarities to Matthew or Florence in that scenario in terms of the rainfall. Both of those storms were terrible flood producers in this region. To be clear, no one is forecasting a Matthew or Florence redux. But on the higher end of the spectrum of realistic possibilities, we can’t adequately rule the Euro model’s scenario out yet. Same goes for the less problematic GFS, of course.

But in addition to the “there’s a storm coming” mindset, we want folks on the coast and inland in the coastal plain to prepare for the potential for a long-duration rain event and the potential for flooding as well. There will be much to monitor this weekend, and we’ll be back in the morning with the latest.