In brief: Gabrielle should become a hurricane by tomorrow as it passes well east of Bermuda and out to sea. Behind Gabrielle, the next tropical wave may develop heading into late next week. But aside from that, it looks pretty quiet, with AI models backing off Caribbean and southwest Atlantic development. A wetter pattern takes hold in many drought-plagued parts of the country, except New England, as mild/warm weather continues.

Tropical Storm Gabrielle

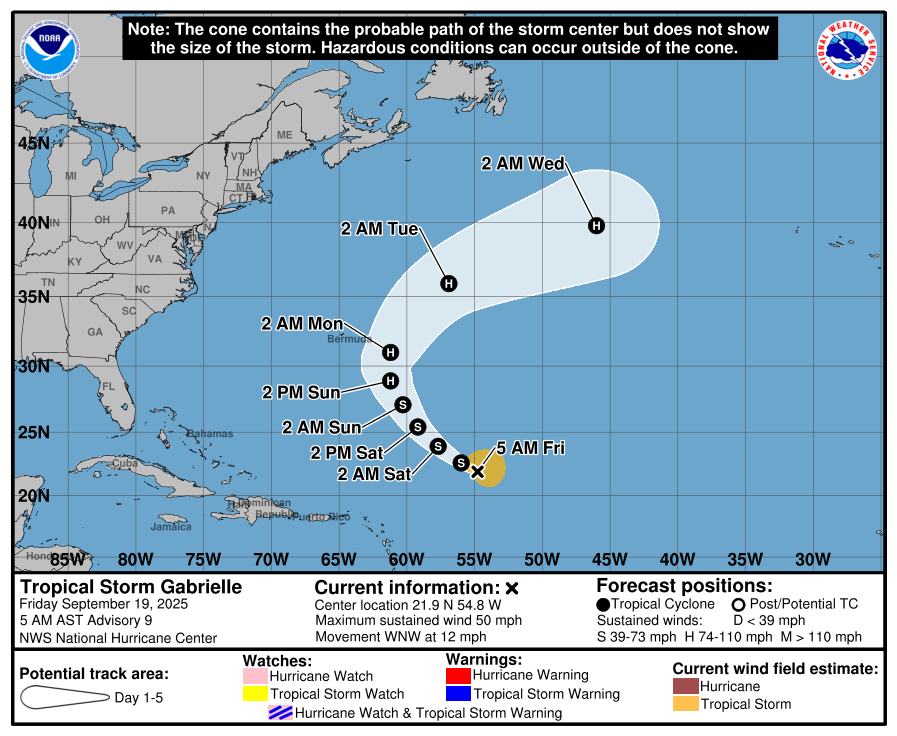

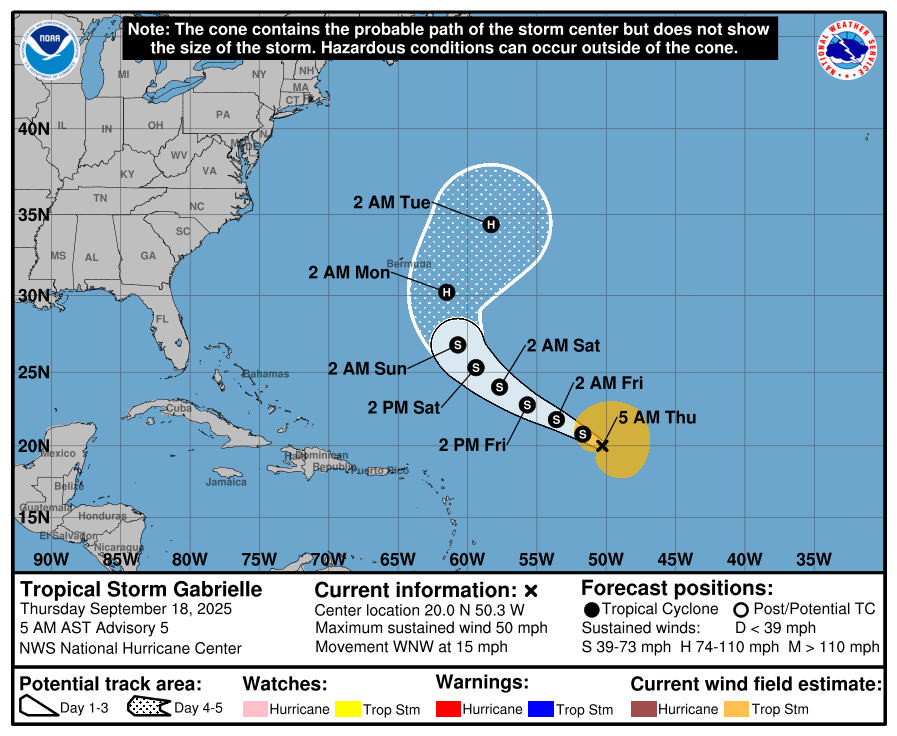

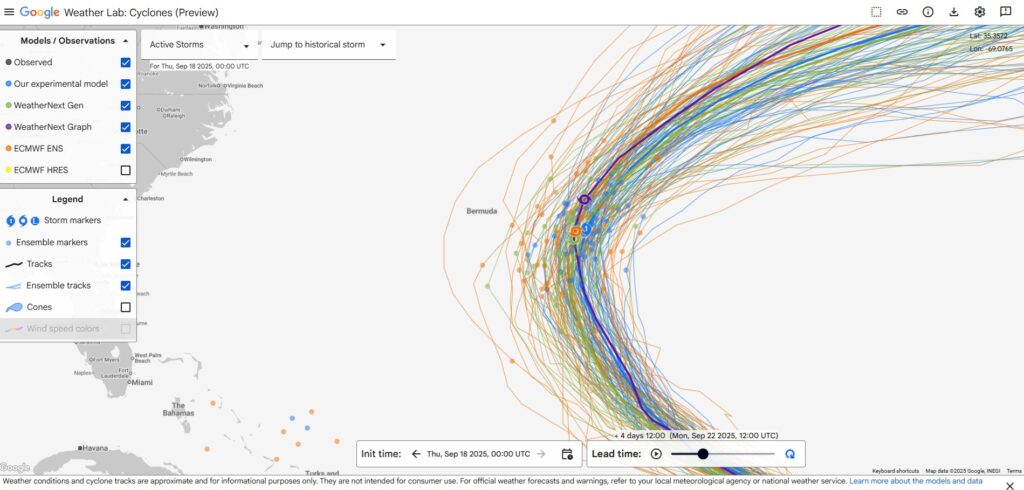

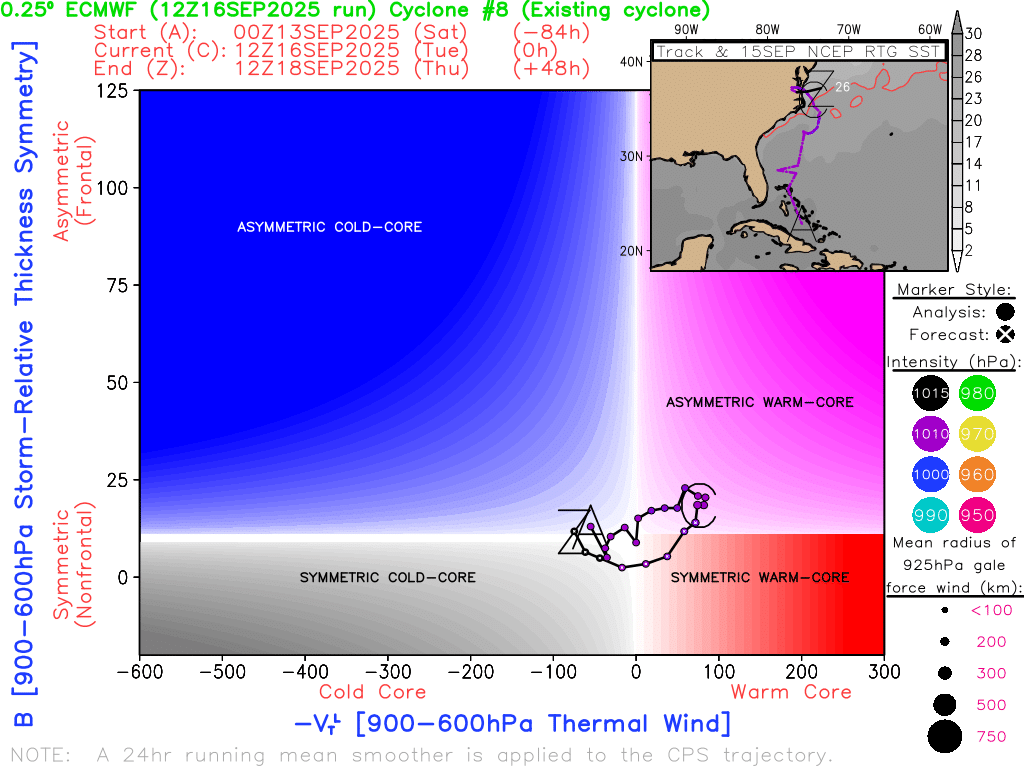

Gabrielle will be passing east of Bermuda today and tomorrow, thankfully, as it likely becomes a hurricane. Winds are currently 65 mph, and it’s looking like it is on the cusp of becoming a hurricane.

Gabrielle is expected to intensify, possibly rapidly over the next 48 hours, and there is a better than usual chance that it could become a major hurricane in that time. Odds of rapid intensification are around 2 to 3 times climatology, which is to say better than usual.

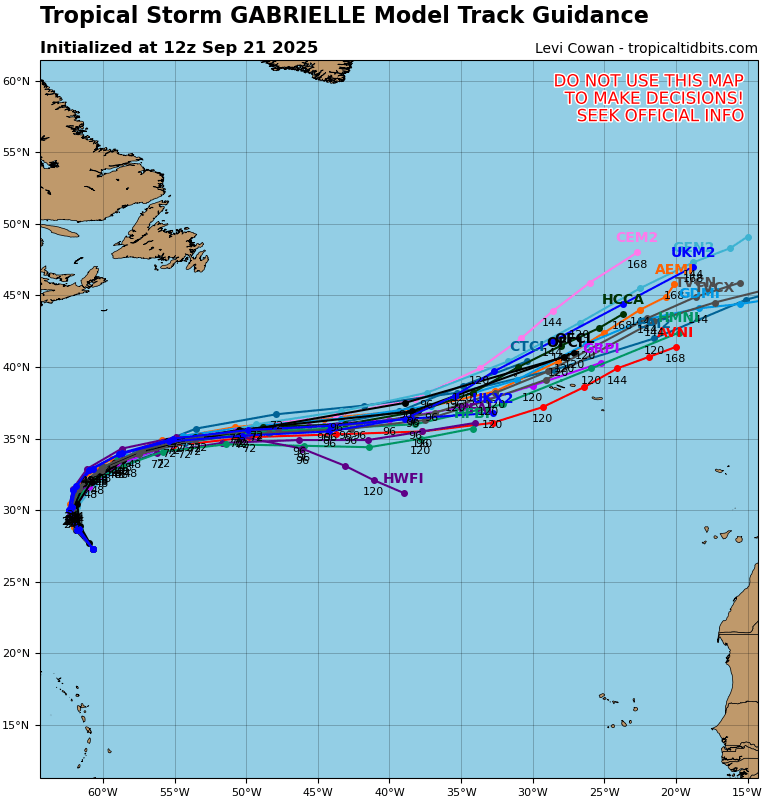

There is pretty good agreement on the track forecast of Gabrielle. It will slowly creep northward over the next 36 hours before making a bit of a hard right out to sea.

Other than a potential brush with the Azores in 5 days, Gabrielle will be just something to look at through midweek.

Behind and beyond Gabrielle

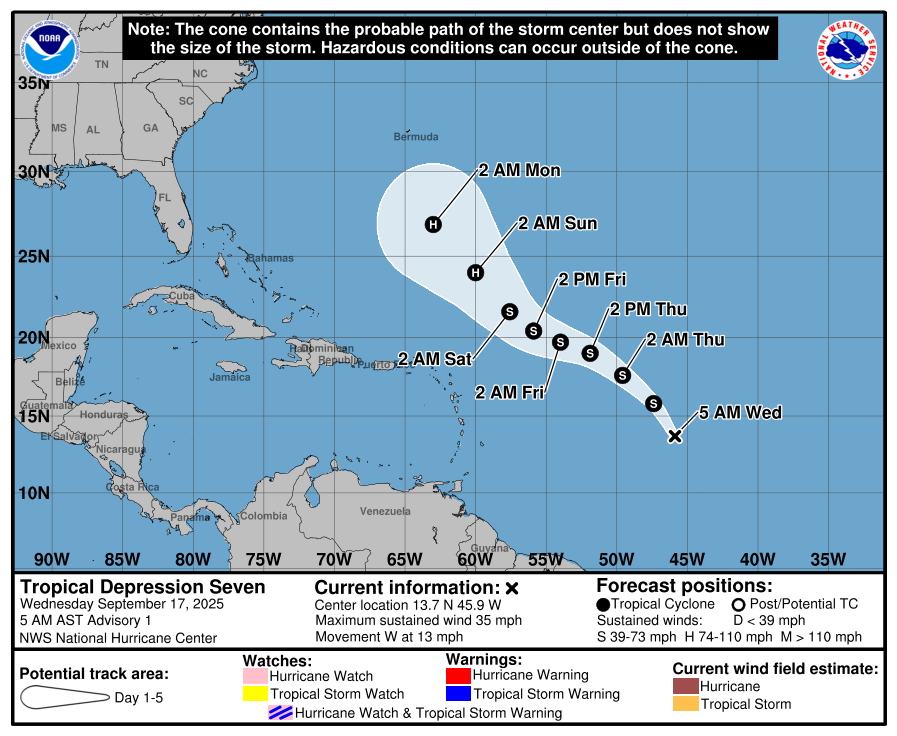

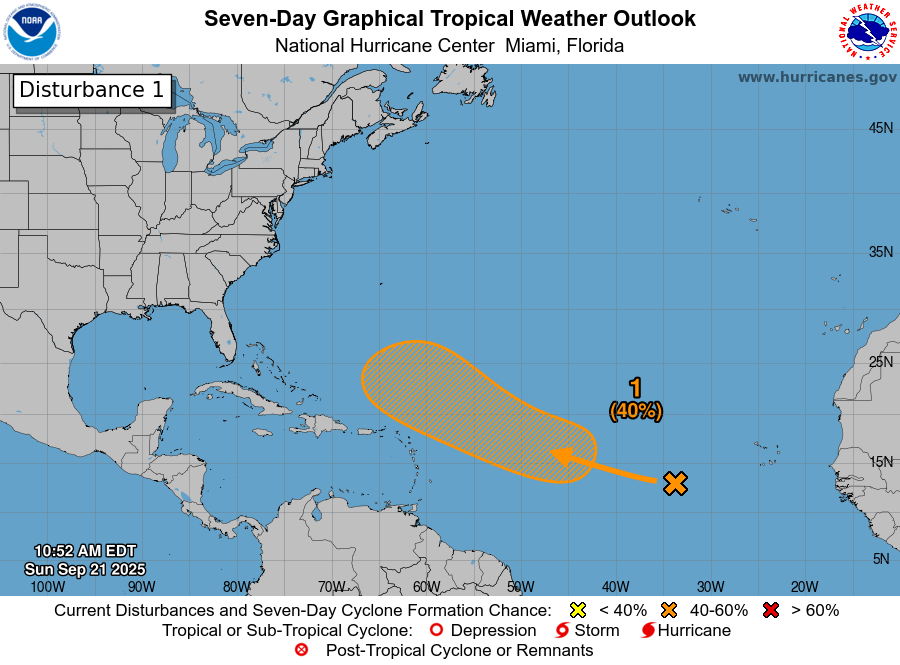

The next wave up has seen some growing potential for development. Odds went from 20 percent the last couple days to 40 percent this morning.

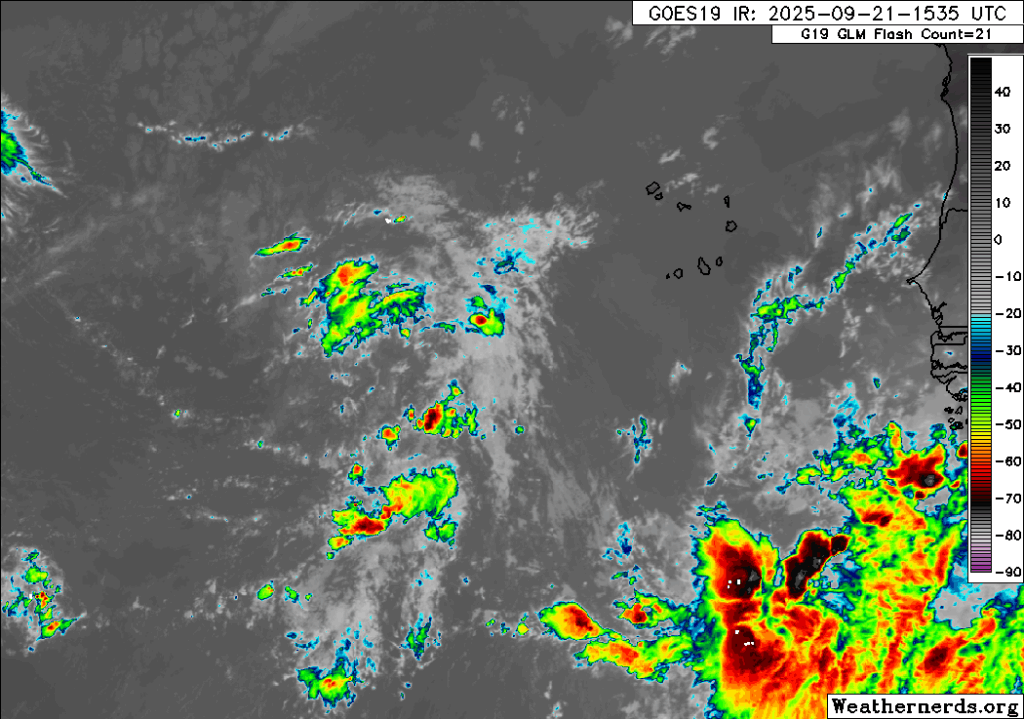

At least initially, this seems to be dealing with the same issues that plagued Gabrielle early on. Dry air and wind shear are limiting any organization.

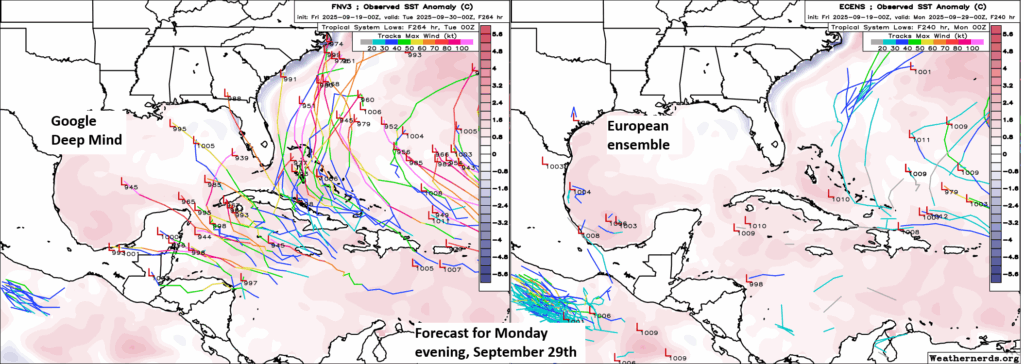

So I would not expect much of this through at least Tuesday or so. Beyond that, conditions are expected to become more favorable. In general, I think this will take a similar track to Gabrielle, but it may creep a little farther west than the current storm is doing.

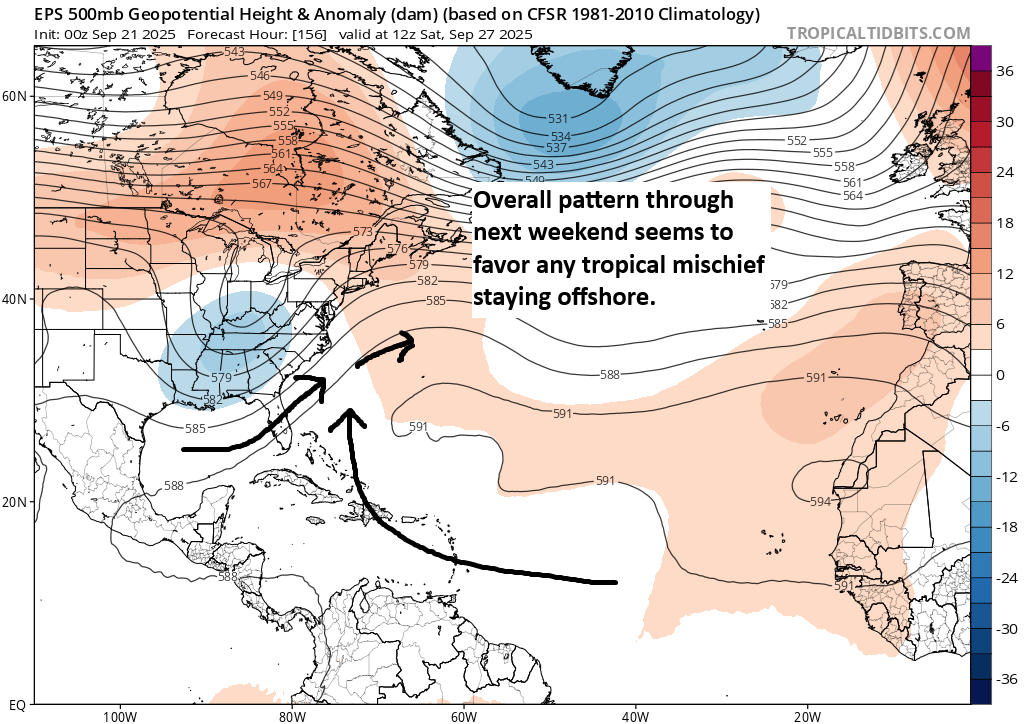

Last week we discussed the AI models and how they were all a bit more bullish than traditional weather modeling on potential northwest Caribbean and southwest Atlantic development. Well, it seems that they have chosen instead to focus more on the upcoming wave rather than that more dangerous area closer to land. You can see the change in the forecast from Friday to today above for next Sunday.

In general, the pattern through next weekend will continue to favor this offshore track of anything tropical in nature. For now, the U.S. is mostly protected from anything on the Atlantic side. And with no real sign of anything imminent in the Caribbean or Gulf, we look good through the end of September.

Perhaps the Gulf or southwest Atlantic will get more active in early October, but that’s extremely speculative.

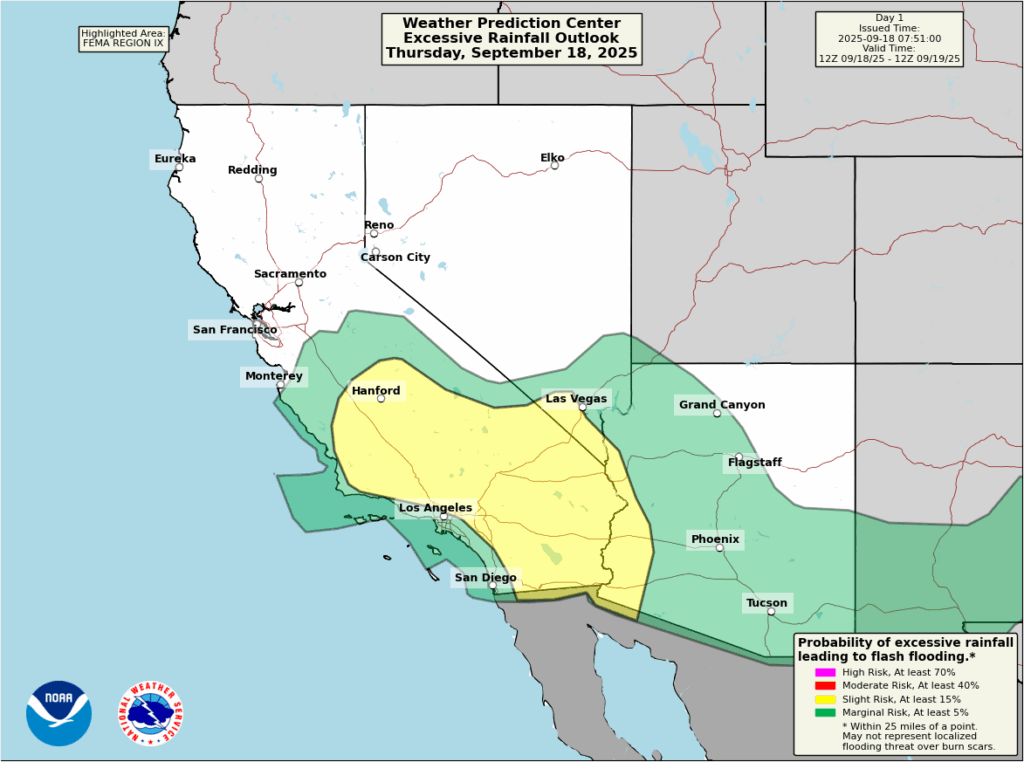

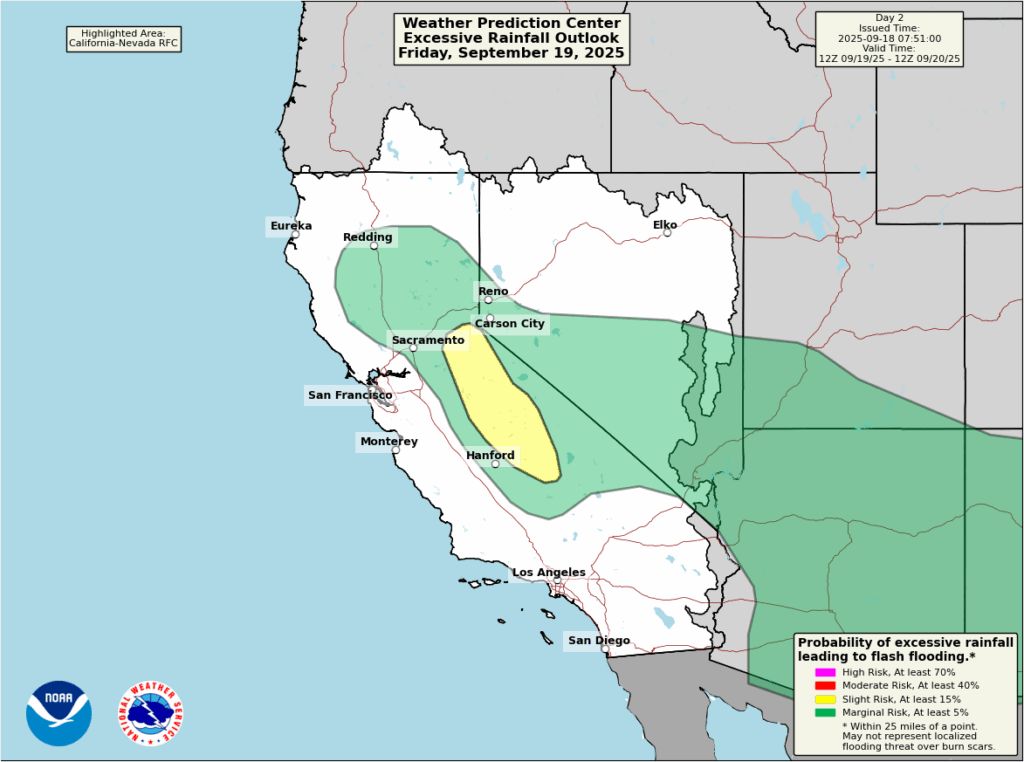

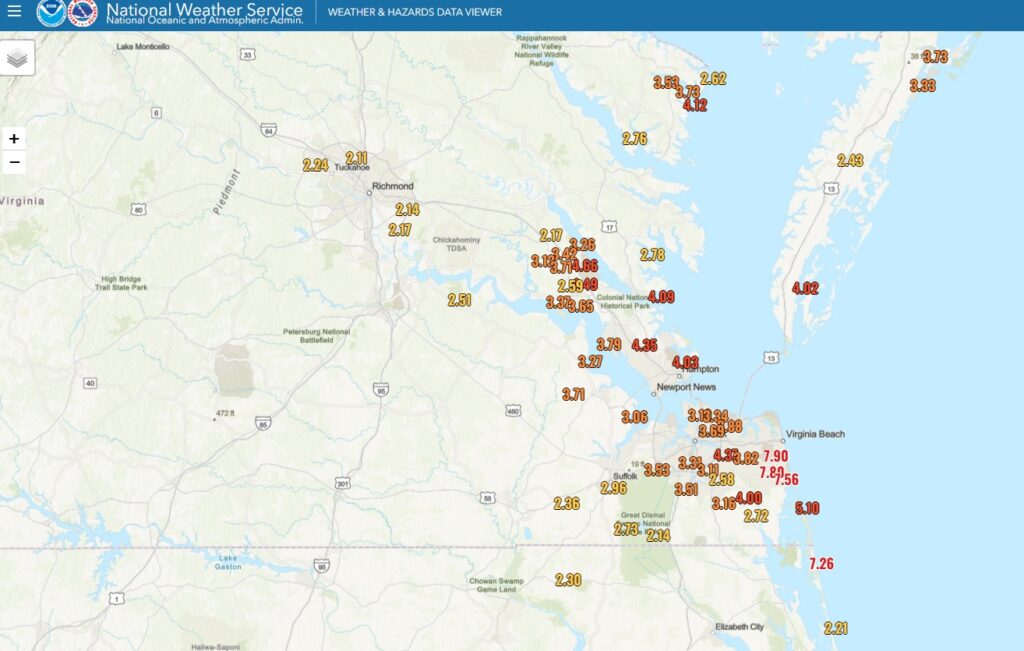

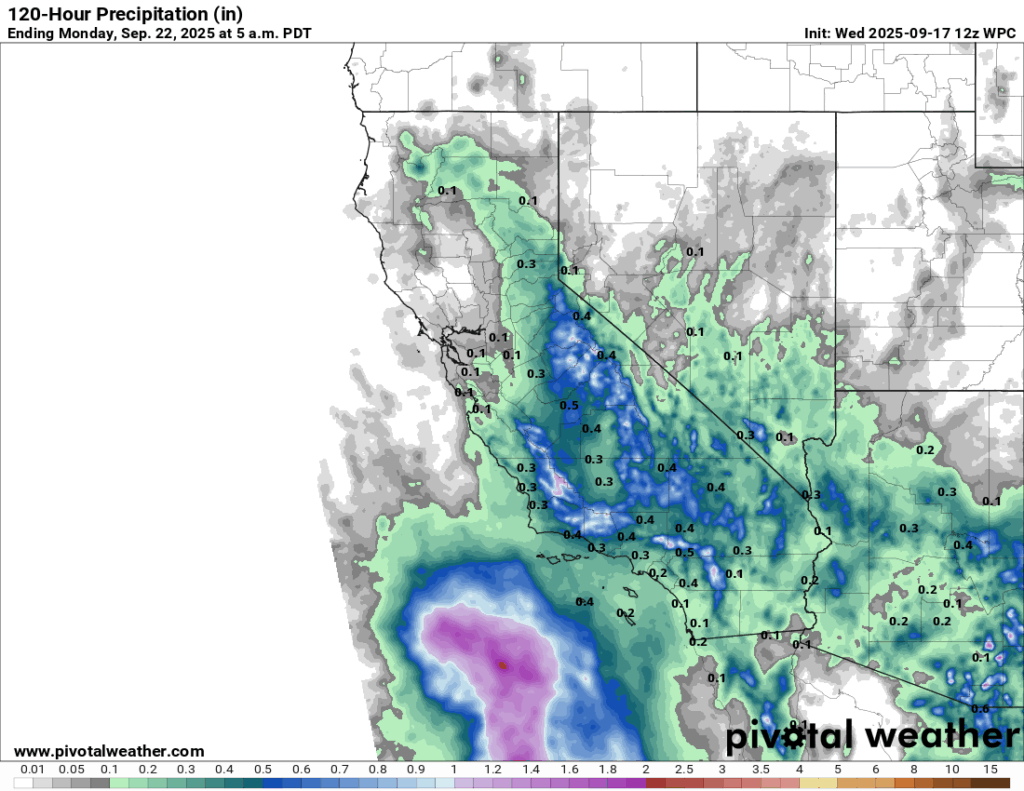

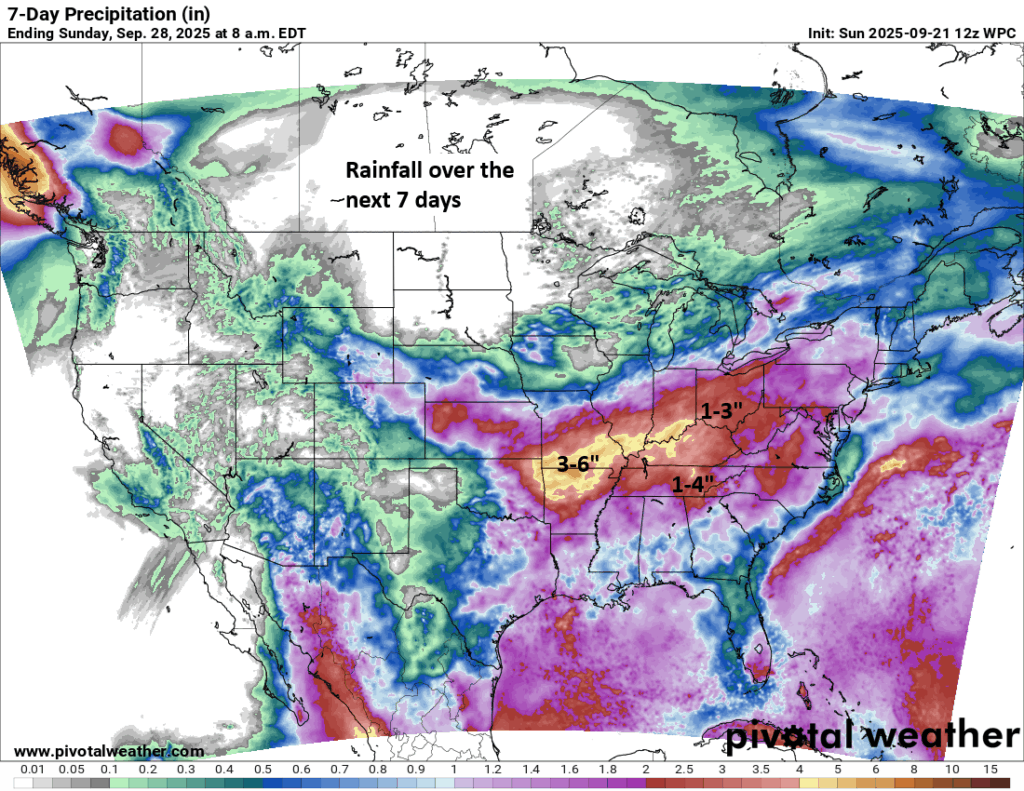

That trough in the upper atmosphere over the Southeast above (blue) indicates that weather will be pretty unsettled over the next several days as well. We should begin to see locally heavy rainfall tomorrow through midweek from the Ozarks into the Ohio Valley. These are areas that are currently under drought conditions, so this will be mostly welcome news. However, the driest parts of New England may not cash in quite that much from this week’s weather, with a growing severe drought from Vermont through Maine. This is impacting foliage season, as my friend Jim Salge reports.

With the heaviest rains, we may begin to see some flooding issues crop up.

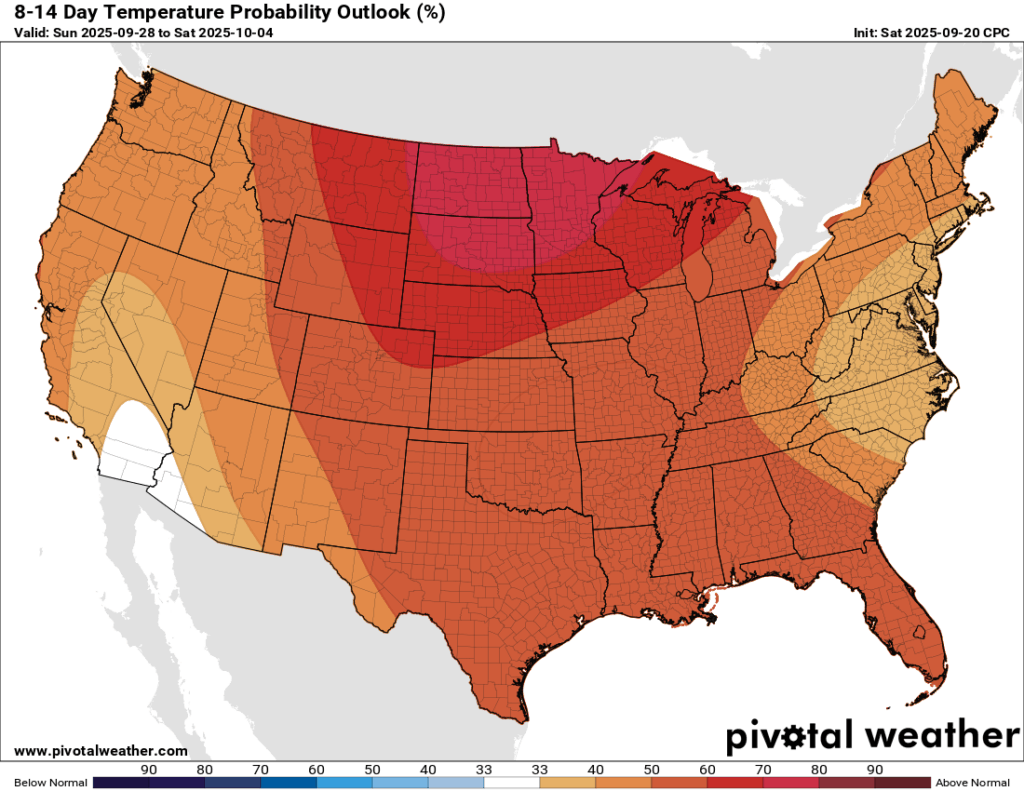

For those of you looking for true, legitimate fall weather, particularly in the southern half of the country, you may need to keep waiting. At times, some frosts may be possible in the usual northern colder spots that typically turn that direction this time of year. But the forecast for days 8 to 14 continue to show good odds of above normal temperatures across the entire country.

But if we can keep any hurricanes away, perhaps it’s not such a bad trade off.