In brief: We explain what’s behind the quiet Atlantic start this season. We also look at how wet bulb globe temperatures can more adequately qualify the severity of the heat next week in the Eastern U.S.

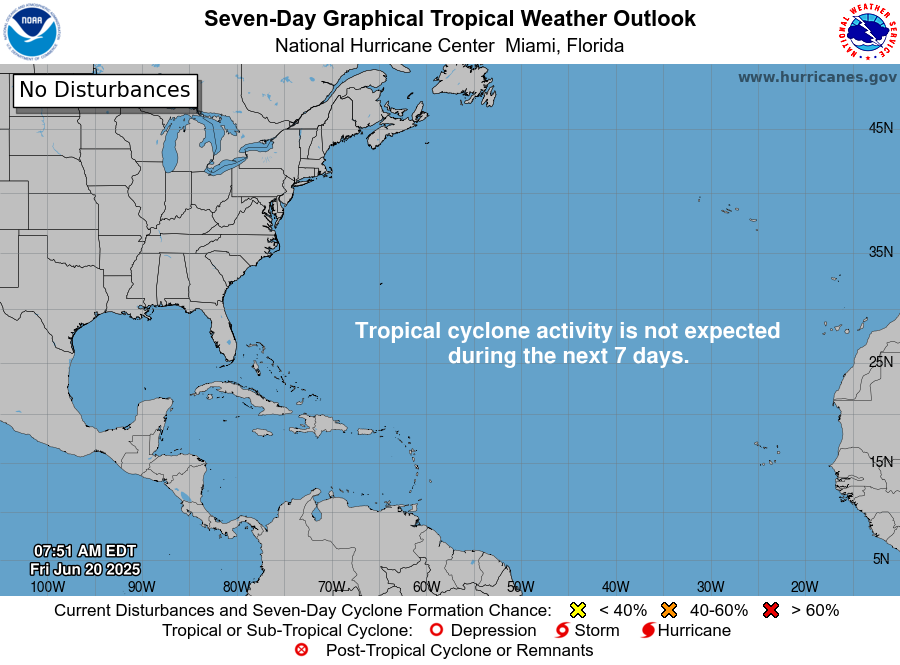

The calm Atlantic continues

This morning at our Houston-focused site, Space City Weather, I explained to our local audience sort of why things have been quiet in the Atlantic. I am reposting that here today, as we have no further items to discuss at this point in time tropics-wise.

Today is June 20th, and to this point I don’t think we’ve said a word at Space City Weather about hurricanes or tropical storms. It’s a refreshing change of pace after recent seasons. In fact, the last year that we did not have a storm in the Atlantic before July 1st was back in 2014. It’s been a while.

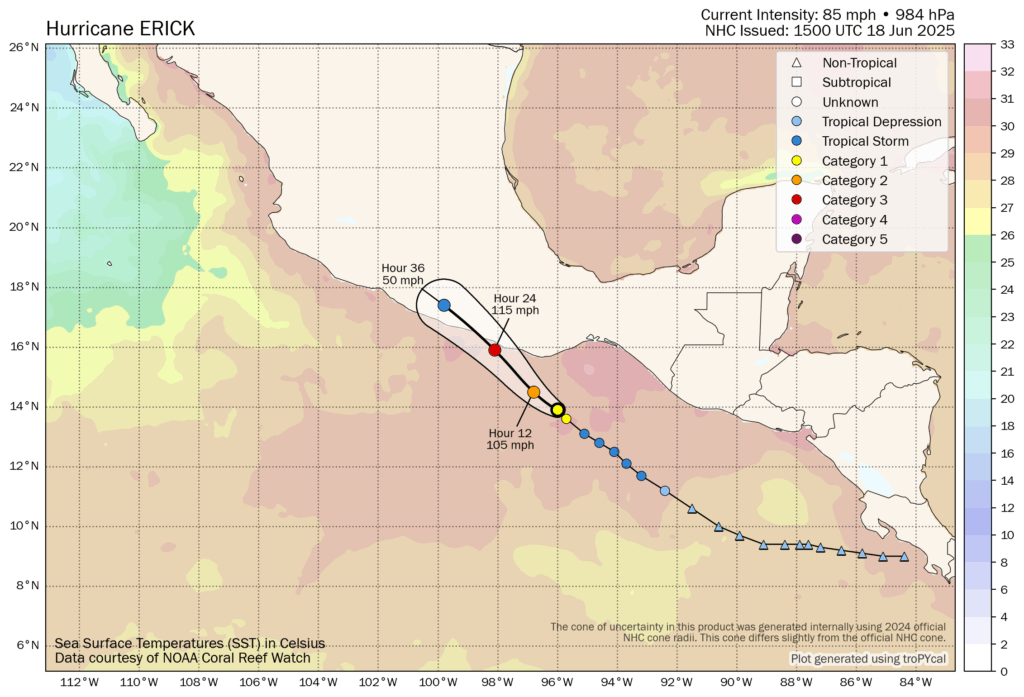

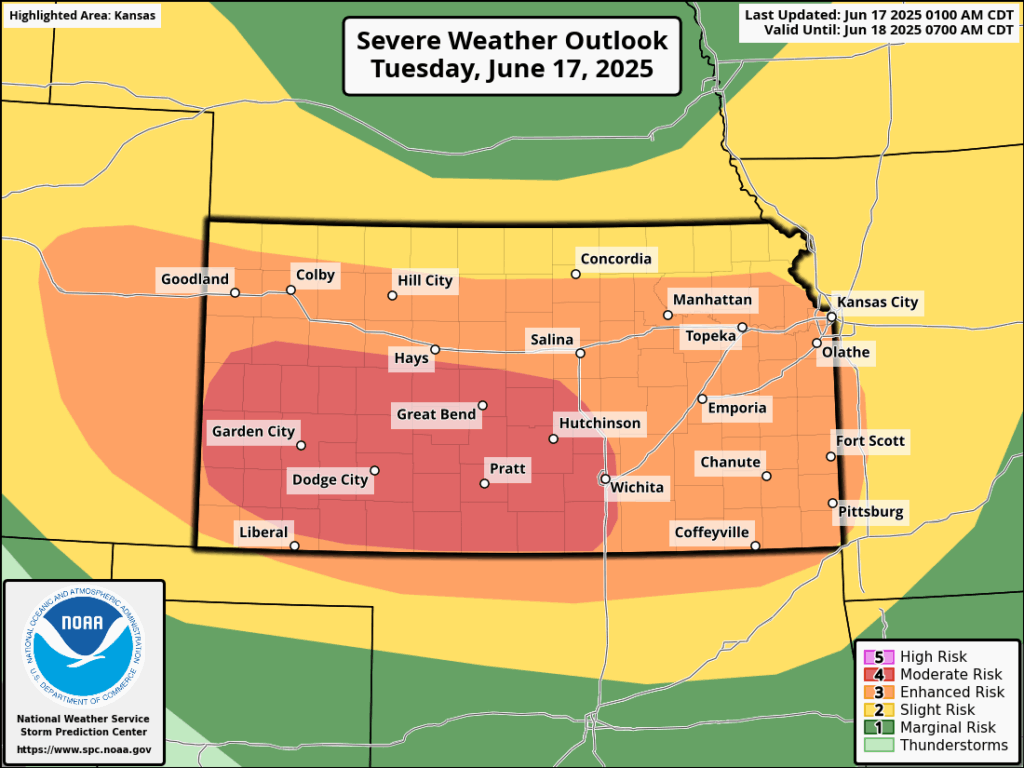

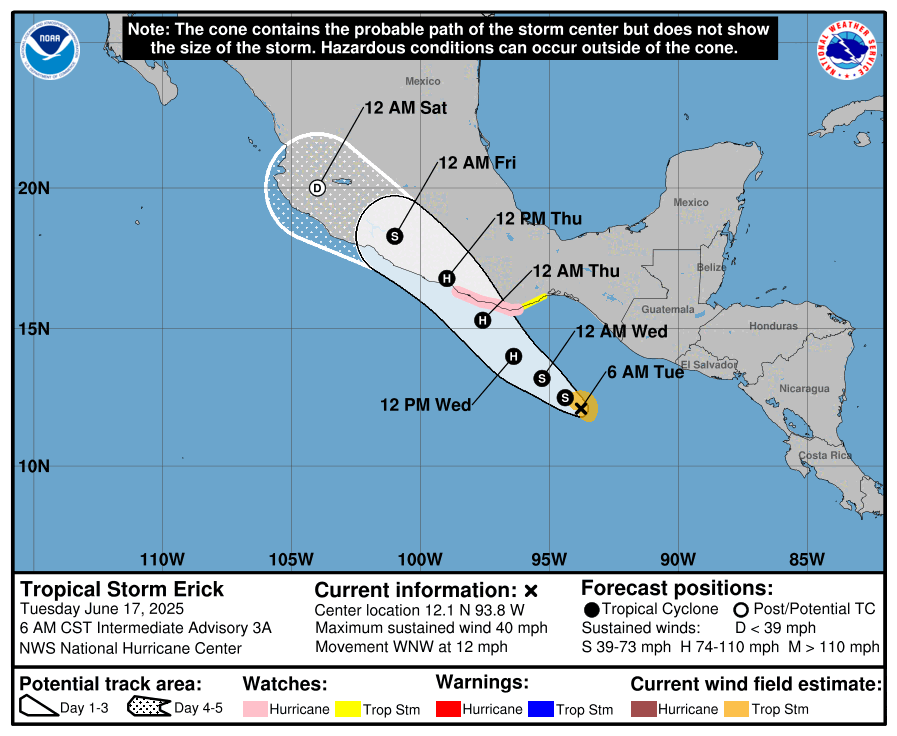

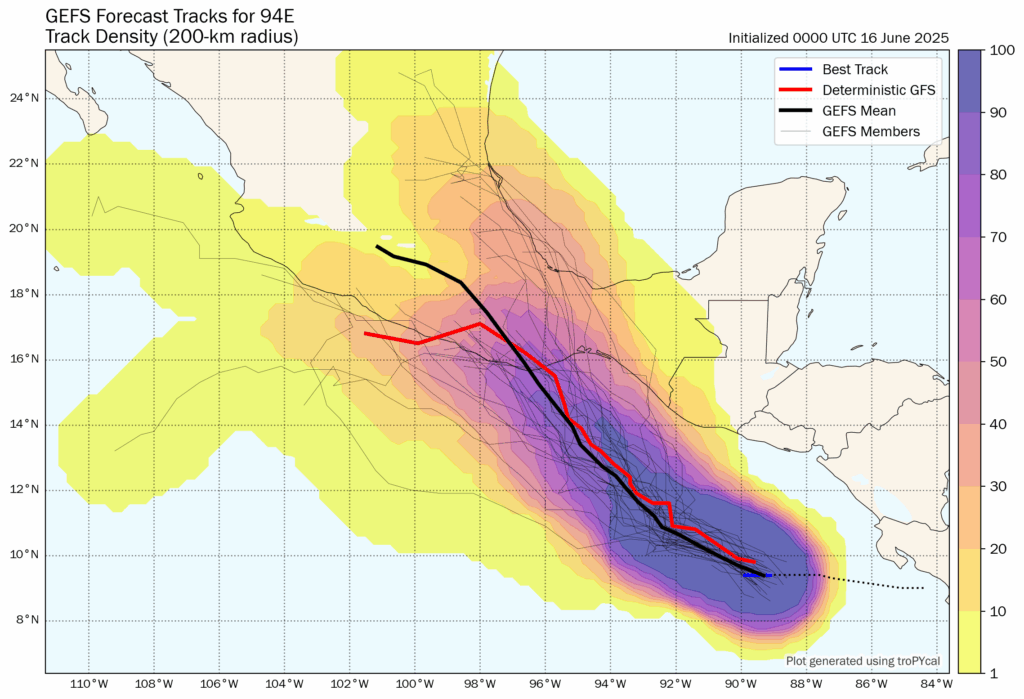

Meanwhile, the Pacific has been churning out storms apace this season, with five so far. Of course, only one of them (Erick, which just made landfall yesterday) was a big storm. Still, the conditions to this point this hurricane season have strongly favored the Pacific. You can thank dust and wind shear in the Atlantic for one, but those things aren’t abnormal, even in recent Junes. So there has to be more at play here.

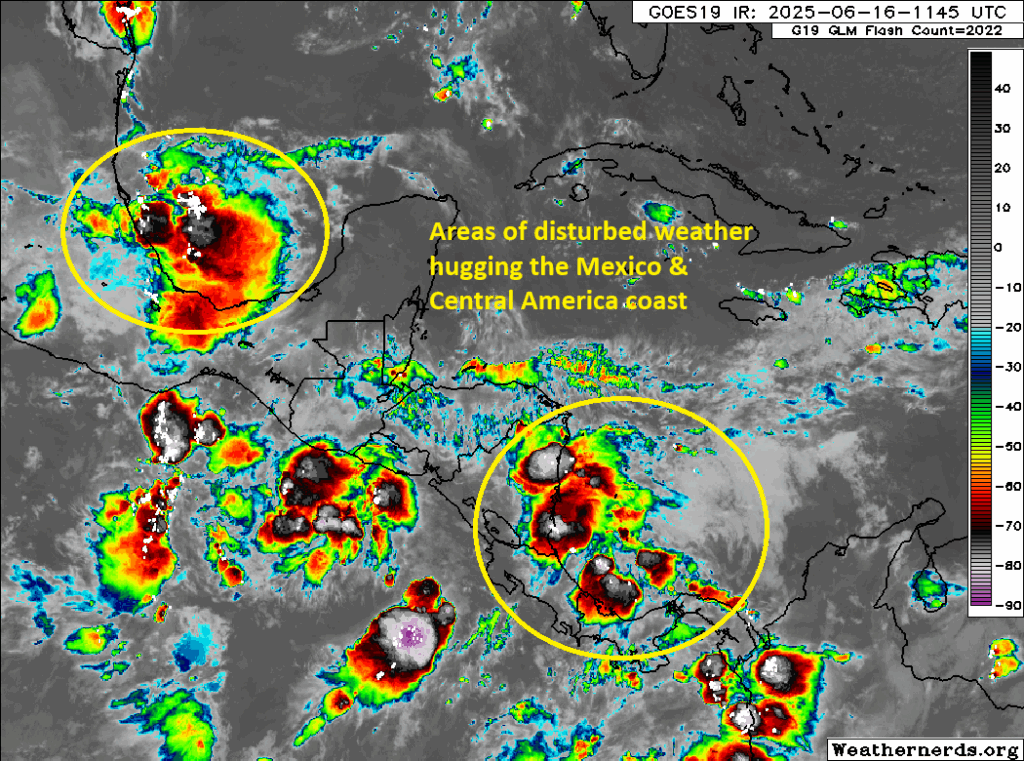

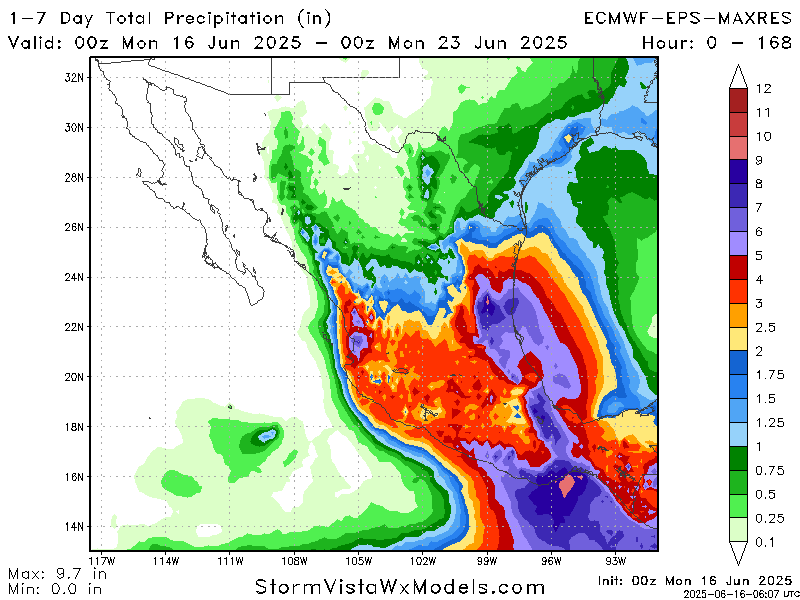

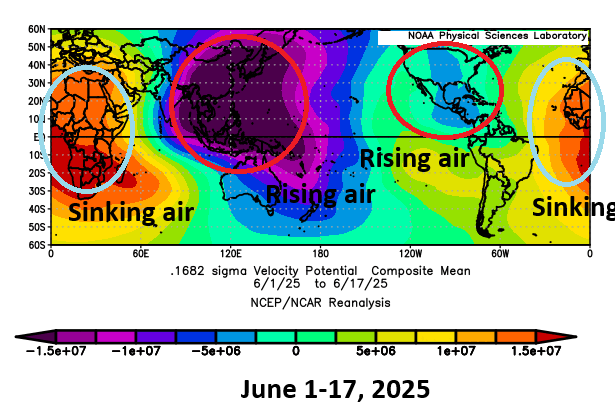

We often talk about the “background state” of the atmosphere. You have individual tropical waves and systems and such through the year, but the background state is important. Are the overarching global weather conditions favorable for development or unfavorable? So far this June, we’ve had the majority of rising air, or a “favorable” background state for tropical development sitting over Central America. Rising air is what helps thunderstorms to develop. Since tropical weather generally moves east to west across the planet, this has meant that most seedlings for development are being planted in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Sinking air sits over Africa and extends all the way across to the Caribbean islands. Sinking air tends to suppress cloud development and dry the air out a bit. By the time any waves can really get going, they more than likely end up over land or kicked into the Pacific.

Over the next couple weeks, this pattern is unlikely to change a whole heck of a lot, but we may start to see slightly more favorable conditions emerge over Africa or the far eastern Atlantic by early July. That said, there are no guarantees that actually means anything. Realistically, the next 7 to 10 days look calm and the 10-to-14-day period has no signs of meaningful change yet.

We do still expect an average to above average hurricane season; June’s activity has no real correlation to the rest of the season, so you can’t decipher any relationships. But when you can get a hassle-free month in hurricane season, you take it without complaints.

Bottom line: You still have time to prepare for hurricane season.

Qualifying a major heat wave

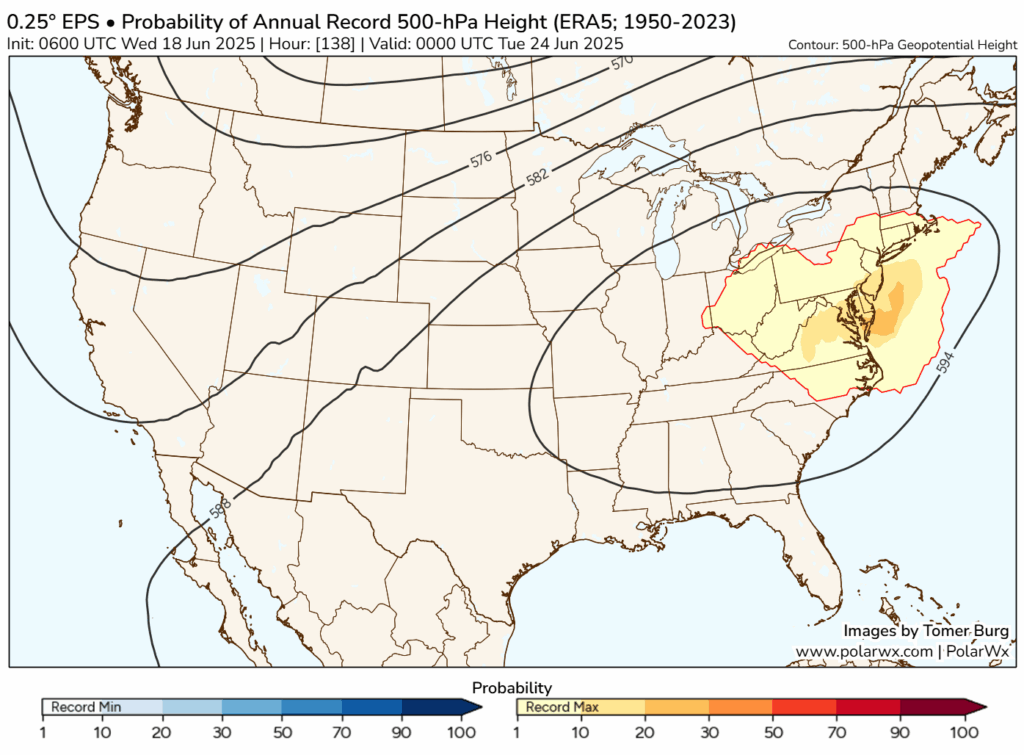

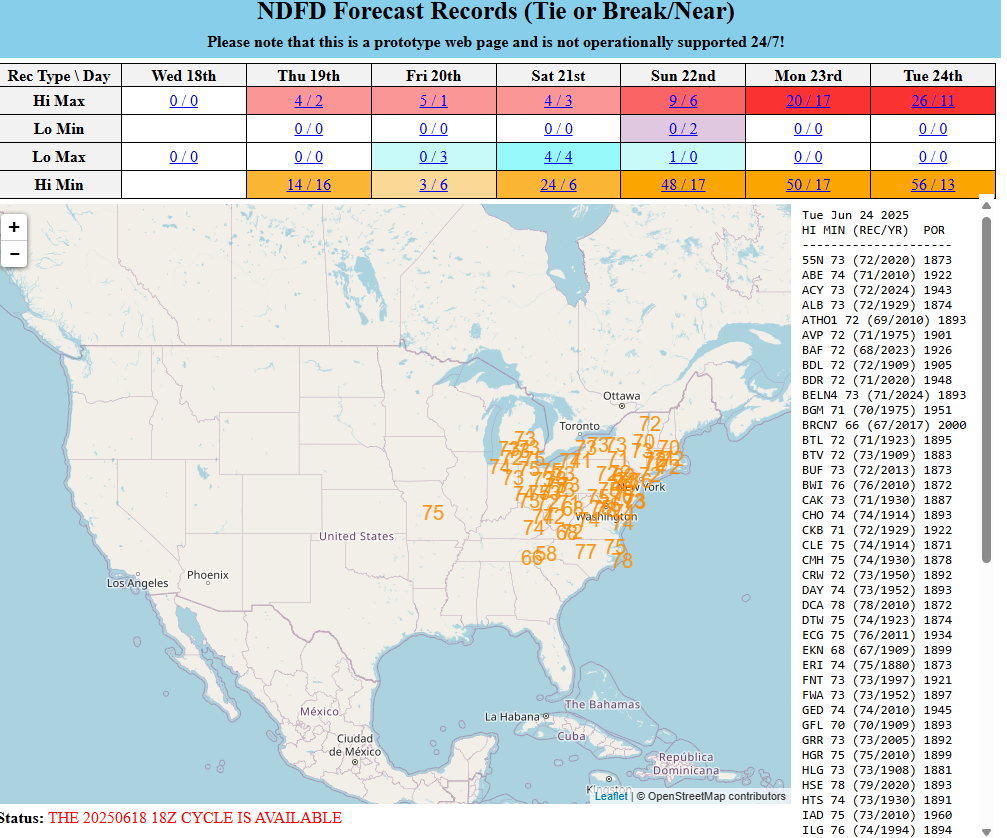

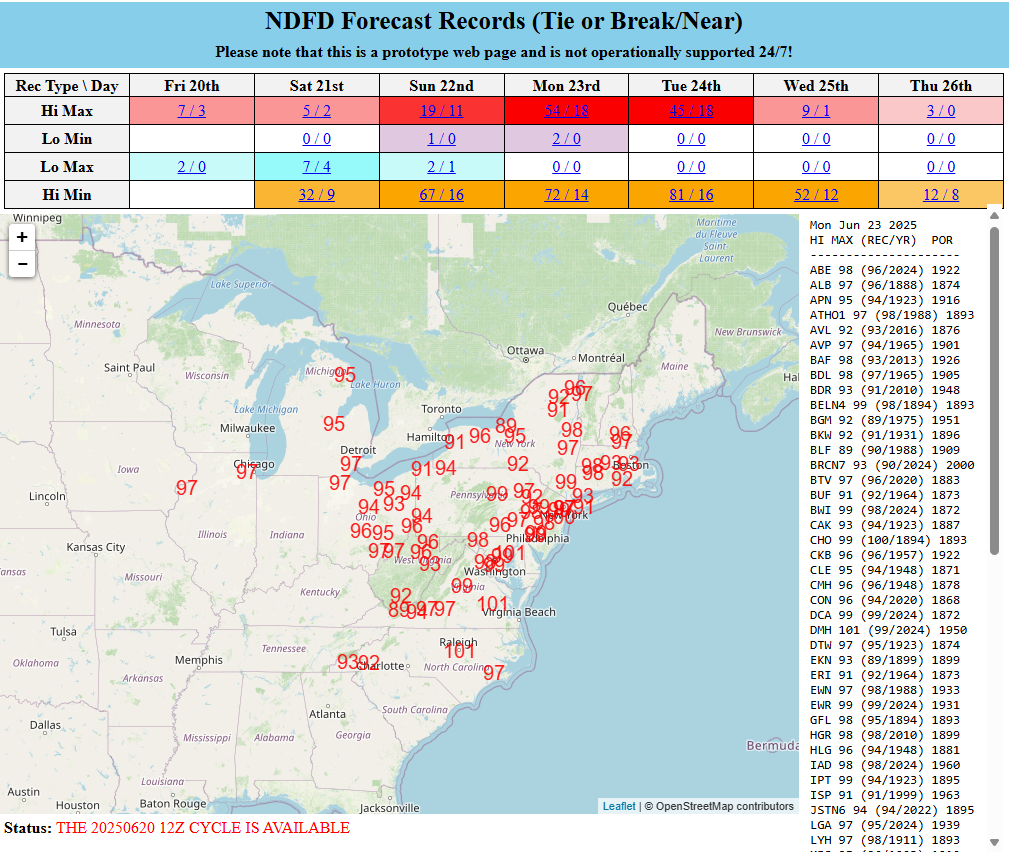

No, it’s not “just summer.” The upcoming heat wave in the Eastern U.S. is expected to break a number of records.

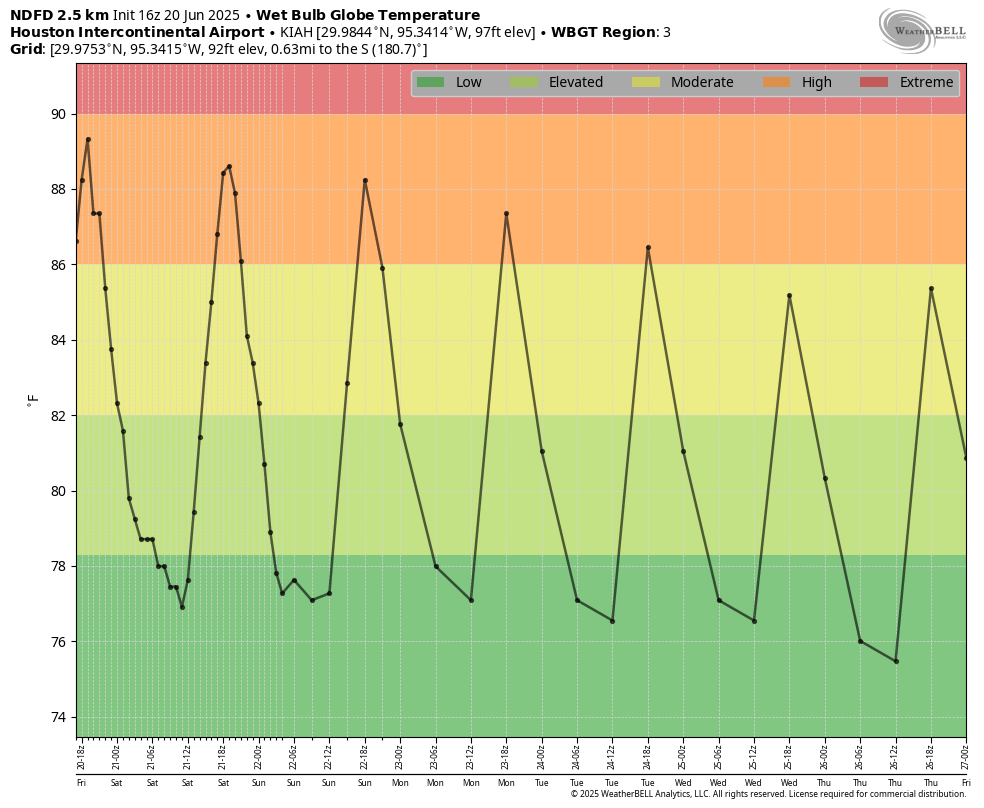

In Houston, we’ve adapted our readers to looking at heat in a more nuanced way. Heat and humidity are common issues here in Texas. We deal with low to mid 90s almost daily from June through early September, with a face-full of humidity and hotter temps periodically peppered in. It’s not pleasant. So things like “heat index,” which is commonly referred to as real-feel or apparent temperature doesn’t always help us to explain heat. Some days can have a 105 degree or 110 degree heat index, but what does it actually mean?

That’s why we often utilize the wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) for expressing heat risks here in Texas. Our forecast is pretty normal right now, without any real significant heat on the horizon. So when you look at our WBGT, you’ll see it sits in the moderate to high range for the next week. High heat is normal in Southeast Texas. But we do not rise to the level of extreme with this forecast.

What is WBGT? It factors in more than heat index (which is just temperature and humidity). A heat index of 105 in Houston means something much different than a heat index of 105 in New York City. So we need more variables. WBGT factors in latitude, sun angle (time of year), wind, cloud cover, temperature, and humidity. It’s a lot more “stuff” than just heat index, so it becomes more valuable. It also helps that it’s a medically accepted guideline for qualifying heat as extreme or high.

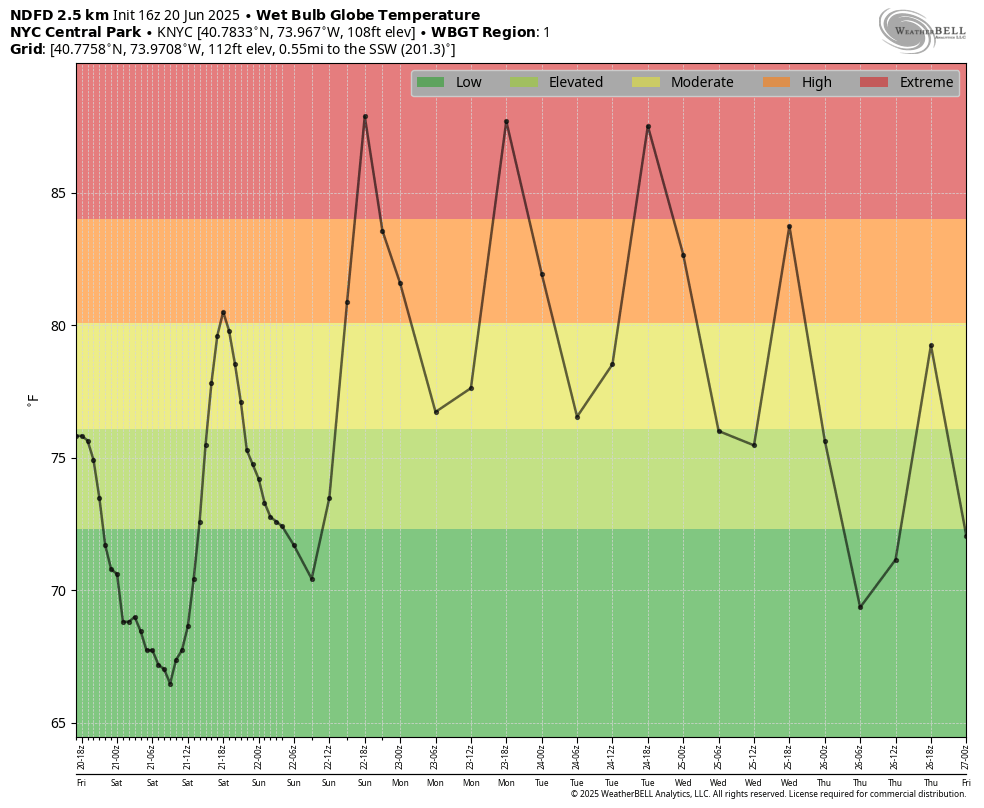

So what of the upcoming heat in the Eastern U.S.? Well, let’s let the WBGT guide us. Let’s start in New York City, which is of course the center of the universe. The upcoming heat rises to “extreme” levels by a fair margin.

This is a hazardous heat for the City. Even at night, we still retain moderate heat values which can cause problems of its own.

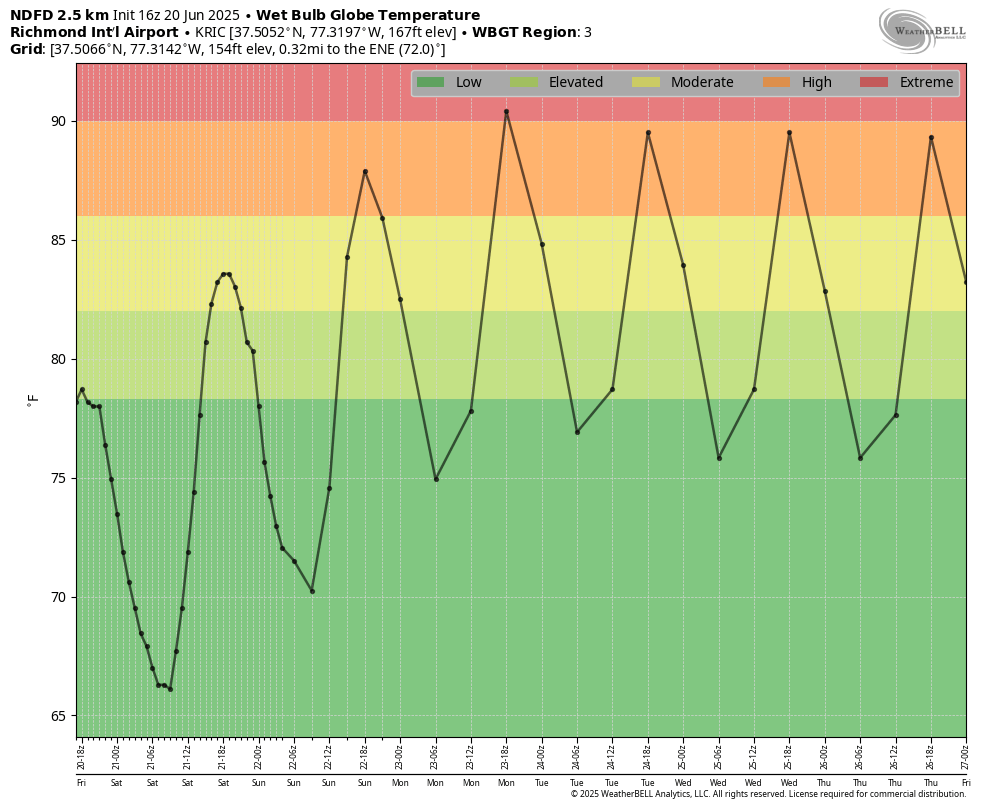

Let’s look at Richmond, Virginia. There, where higher heat is a little more common, the WBGT levels are forecast to just barely get to extreme levels.

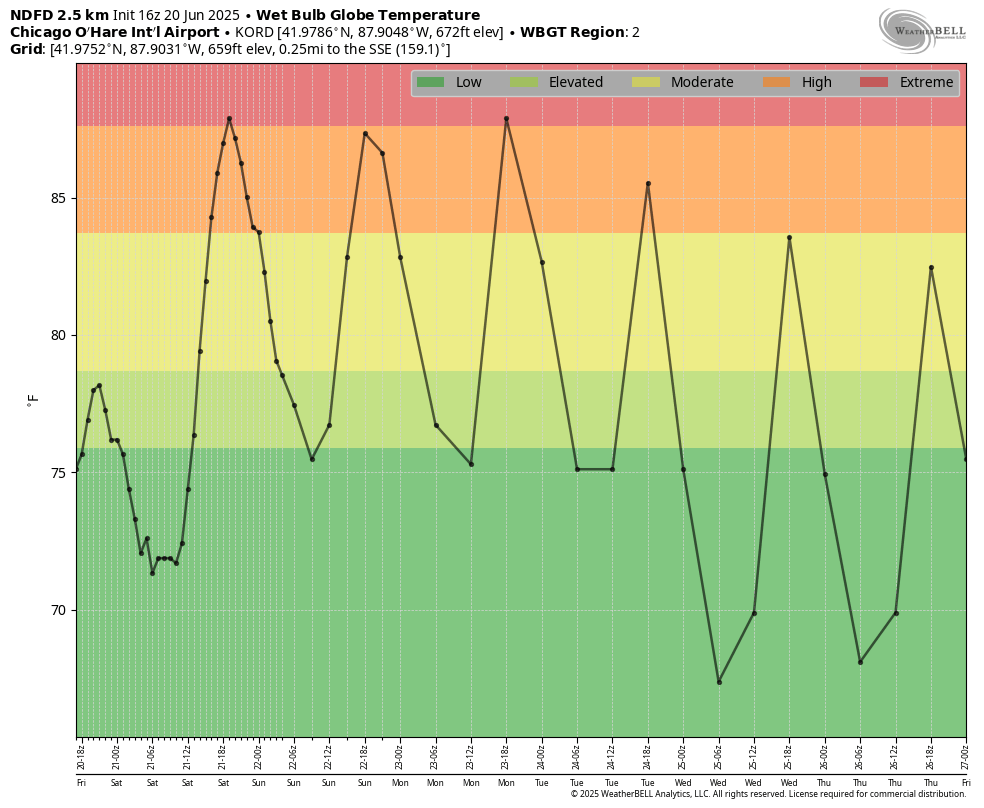

Since the region of the country is what sets the scale, extreme heat starts with a WBGT of 84 in New York but 90 in Richmond. Let’s move to Chicago, where they’ll likely see borderline extreme heat too.

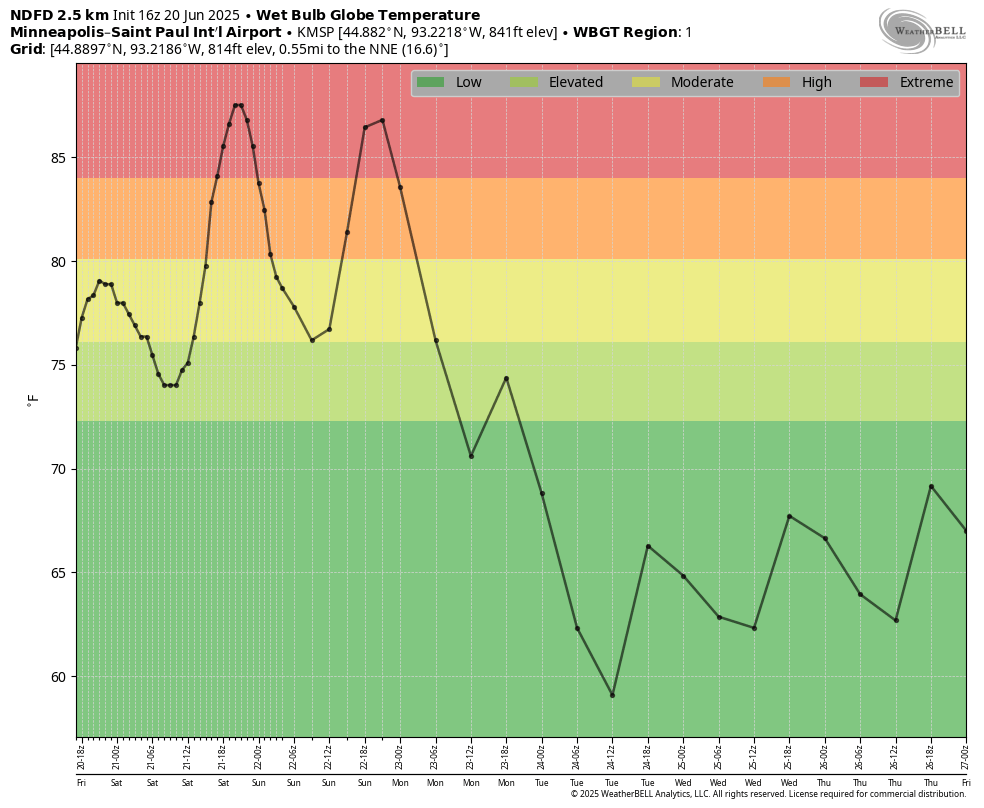

While the focus is on the East, let’s not forget the Upper Midwest. A short-lived but powerful dose of heat is going to set in this weekend, with Minneapolis likely experiencing two days of extreme heat before temperature fall off a cliff.

In some places, the heat is going to sit around deep into next week, and it’s possible that some forecasts will need to be adjusted hotter over time. The ridge of high pressure responsible for this heat wave should begin to break down next weekend.

So what is the point of this? Extreme heat is not “just summer,” and when you utilize metrics like WBGT, the data becomes very clear. Also critical is the duration of the heat and how warm it stays overnight. In New York, for example, nighttime lows may struggle to drop below 80 degrees. That is exceptionally warm there. Going back to the 1860s, Central Park has only recorded 69 nights that failed to drop below 80 degrees. Over a third of those have occurred in just the last 30 years, due in part to climate change and warming oceans. It’s been a minute since nighttime temperatures that warm have occurred in New York, with the last 80 degree night recorded in July 2020. The longer those warm nights occur, the more compounding impact the daytime heat has, and the more hazardous it becomes, particularly for elderly people and those with poor air conditioning.

Anyway, bottom line, be smart about the heat in the East next week. Practice heat safety and drink plenty of water.