Hurricane outlook season continues

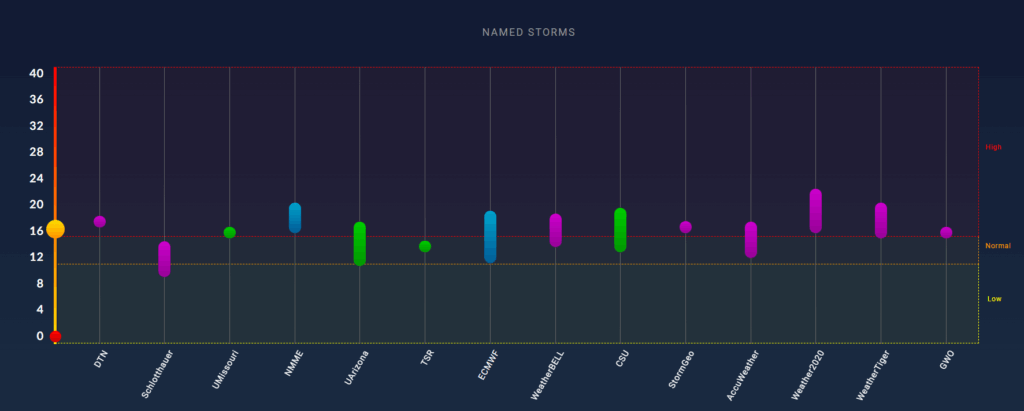

We focus a lot on Colorado State’s hurricane outlook, but many others are beginning to issue their own as well. This includes The Weather Company and Atmospheric G2, which expect a slightly more active season.

A number of outlooks are now public, and there seems to be a consensus that most entities buy into an active season but perhaps not a hyperactive one. Recall, last year’s hurricane forecasts were pretty unanimously doomsday, which is kind of what happened (though not in the way we all expected). This year’s are not. But the message should be that it only takes one storm, and you should prepare this season as you would any other one if you live in hurricane country.

Tropical weather outlooks from the NHC will resume in about 3 weeks.

One last note: A recent paper published in Nature Climate Change focused on storm surge extremes, and it turns out that we may be underestimating them at a majority of coastal sites due to observational gaps. As it turns out, more data is good. Which leads us to…

Putting the “fun” back in NOAA funding

In summary: There has been some good news recently, but the negatives continue to outweigh the positives.

Obviously, we are watching the developments surrounding NOAA and the National Weather Service and budget issues very closely. Here’s an update on where we stand and some apolitical thoughts on what’s going on.

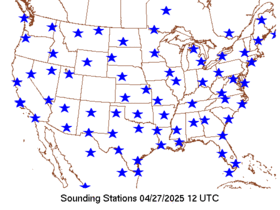

One of the major issues we’ve discussed recently has been regarding staffing cuts leading to fewer weather balloon launches each day. That continues to be a problem. There has been some minor progress, however. Representative Mike Flood, a Nebraska Republican congressman has been one of a handful of political leaders that has been fairly vocal on the risks of this. In short, he gets it. The good news is that balloon launches are scheduled to return to Omaha, and improvements in launch frequency are slated for some other High Plains and Northern Plains locations. The bad news is that staffing is coming from other offices. In other words, the risk is that we may be creating more problems by solving one problem.

A good example of this is happening here in Houston where the local forecast office will soon be without a meteorologist in charge, a warning coordination meteorologist, and a science and operations officer, the top 3 leadership positions in the office. While those will be filled with reassigned employees, it’s pretty evident that hiring freezes, and “strongly encouraged” early retirements are creating a math problem that will only be solved by re-hiring fired probationary employees (which the current administration is against) or bringing in new hires (which the current administration has shown no appetite for to this point). 2 + 2 + 2 is still 6 no matter if the person is in Omaha, Houston, or Fairbanks. The government allowed or “strongly encouraged” hundreds of years of cumulative forecasting experience and mentorship walk out the door in the last 2 to 3 months. So, while there are some positive signs popping up, more must be done. We are objectively worse off in terms of the National Weather Service than we were four months ago and we’re not trending better enough fast enough. Without being overly activist, I’ll just say that these are issues you should raise with your members of Congress if they concern you.

A lot of what is happening is targeting climate change research, but what a lot of the folks enacting these cuts don’t fully understand is that by targeting that, they’re likely to cause significant collateral damage to weather forecasting in the process. One good example of this was the recent failure to renew a bunch of regional climate center funding earlier this month, which caused several data sources used by meteorologists (including myself) on a regular basis to go offline. Thankfully, that funding was renewed, but the passback document unearthed recently suggests it will not be long until that’s back on the chopping block. I am also especially concerned that cuts to the GFDL, AOML, and NSSL labs, collateral damage in this fight, would cause outsized harm to weather research and forecasting. This point continues to need to be reiterated and raised. This isn’t about your stance on climate change, it’s about fundamentally degrading the capability of the NWS to achieve its mission of protecting life and property.

For a unique and helpful perspective on some of the bureaucracy here, I encourage you to follow Alan Gerard’s Substack, “Balanced Weather.” Alan is a recently retired veteran of NOAA and is very measured in his explanations. He is also anti-hype and focuses on the issues of note. A worthy newsletter to tap into.

Another thing to really understand in this whole thing: How much is a weather forecast actually worth? Planet Money recently re-aired a really good feature about the value of weather forecasts. Since 2009, when thinking of just hurricane forecast improvements alone, it’s estimated that roughly $7 billion has been saved thanks to government-driven research. And again, that’s just on hurricanes. It’s a short segment that’s worth 10 minutes of your time.

One of the most common questions I’ve heard because of the cuts is “Are you seeing impacts?” I believe we are seeing some of the issues of the reduced weather balloon launches rear their heads in real time. I have begun to notice that some higher-resolution short term models are struggling a bit more than usual in capturing significant thunderstorm complexes. Of more interest is seeing global models, like the European model do a great job depicting a threat 3 to 6 days ahead of time but then misplacing it within 3 days. Why is this happening? Theoretically, it would fit the idea that a lack of upper air data in a region would contribute to this. Is it officially the reason? No. We have to be careful, as it’s not unheard of for this to happen in spring. But it merits continued monitoring ahead of hurricane season. The takeaway right now is that missing upper air data is probably having some impact on our forecasts but mostly in a “cosmetic” fashion or “slightly higher uncertainty than usual” so far. Time will tell.