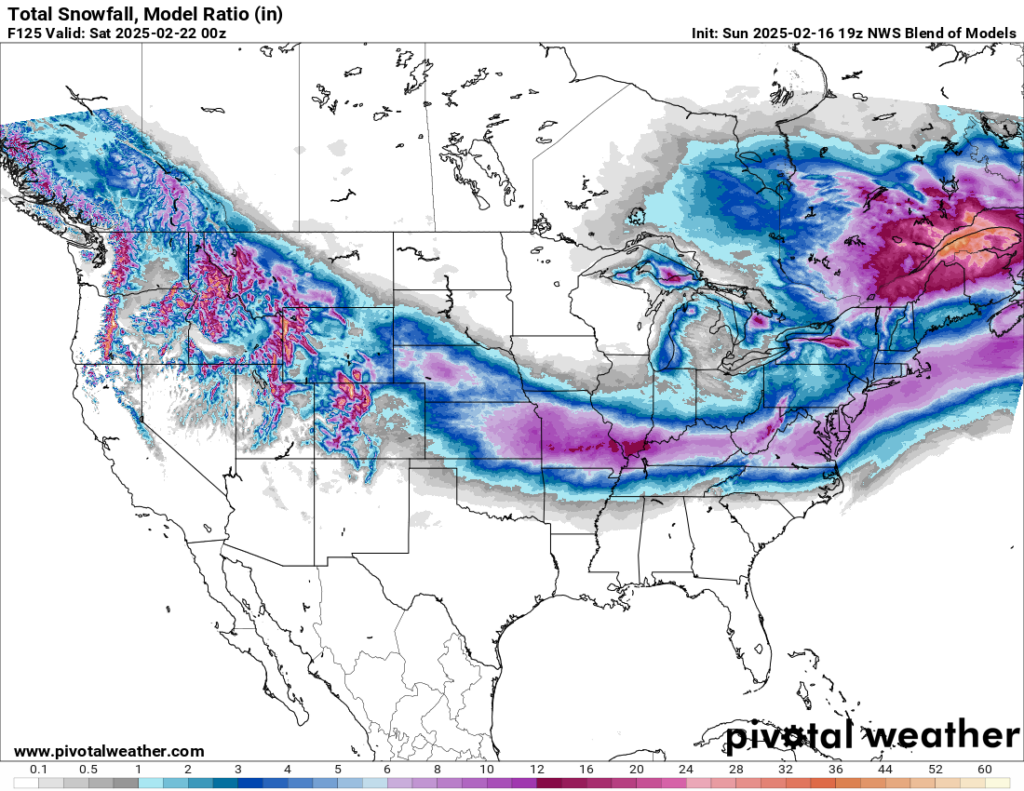

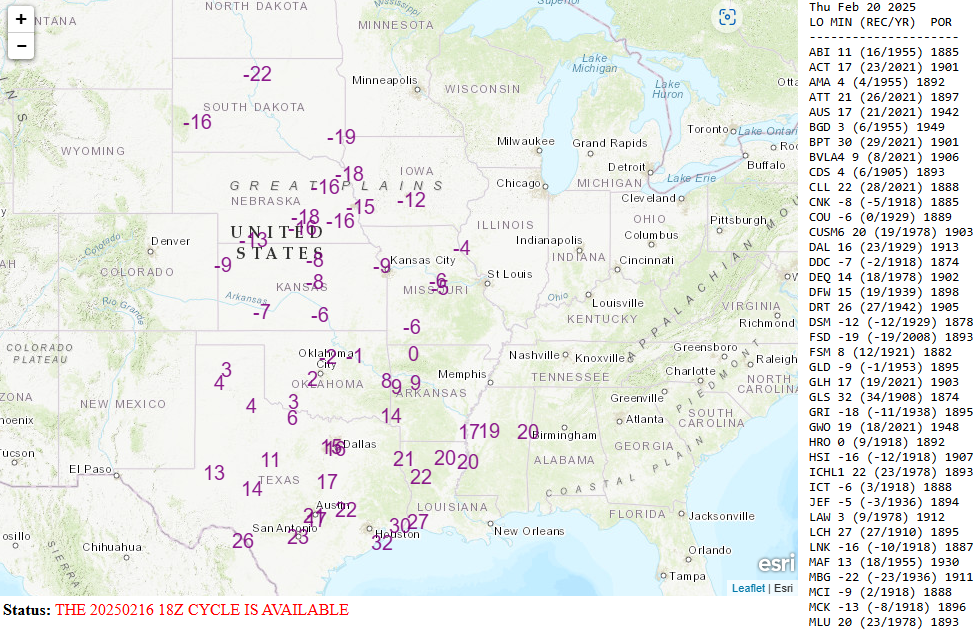

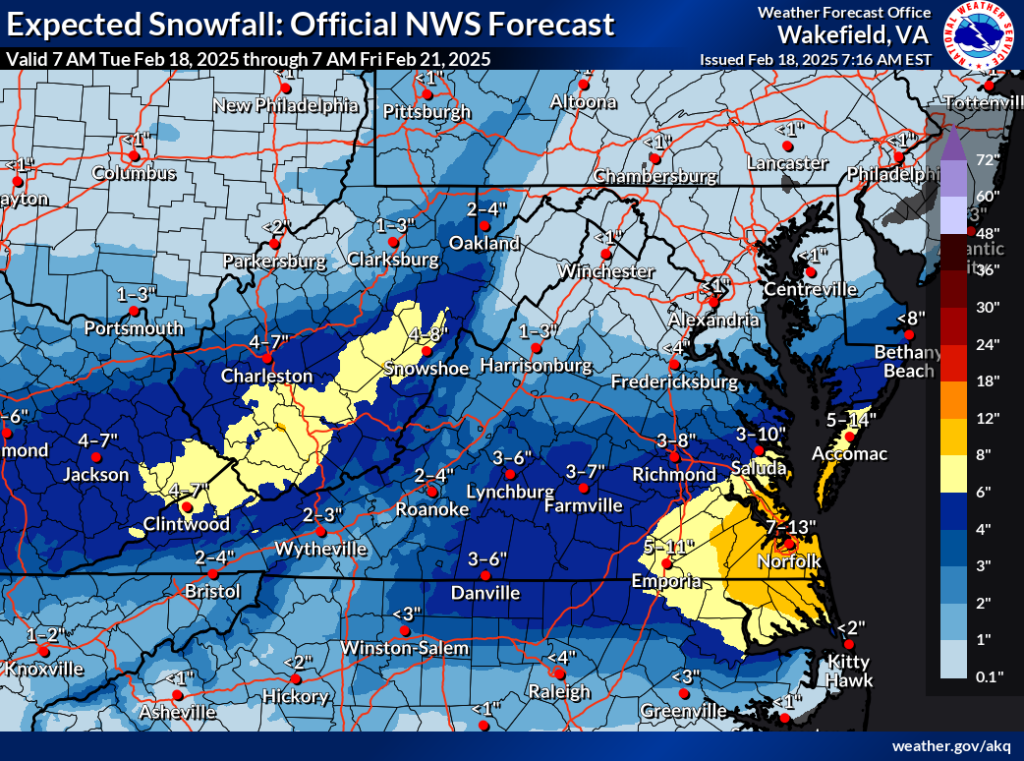

Funny things happen in the world of weather. As a meteorologist, I have seen more than my fair share of busted forecasts, surprise hits, forecasts that actually panned out, and surprise misses. Another snow event looks likely to join the long, long list of the ones that got away for parts of the Mid-Atlantic. As of Sunday we discussed a winter storm both in the context of the Mid-South, which is still intact but also for the Mid-Atlantic. Just for comparison, here is the snow forecast over the last several model runs for PM Wednesday and Thursday morning in the Mid-Atlantic.

That is about as ugly an outcome as I’ve seen for a snow lover. And that’s the European model, one of the better performing ones historically with snowstorms. So what the heck happened?

Well, basically, nothing comes together in time. If you look at the last few days of models runs from the European model, you can see a slow trend away from meaningfulness. On Saturday, the Euro depicted a 987 mb low off Delmarva. On Sunday it shifted a little to the southeast, and then yesterday, it popped up to 1001 mb and well southeast. The consequence here is that the storm basically never gets together now off the East Coast in a position close enough to deliver snow to the Mid-Atlantic, with the exception of maybe the Virginia Tidewater and northeastern North Carolina.

You can look up higher in the atmosphere and see how the more bombastic idea of a storm near the Mid-Atlantic coast gradually faded over the last few days too.

You can also look under more of the hood here and see how the ensemble members of the European model summed things up. The number of members with 4 inches of snow or more got to 80 or 90 percent in portions of Delmarva on Sunday before plunging to 10 percent yesterday.

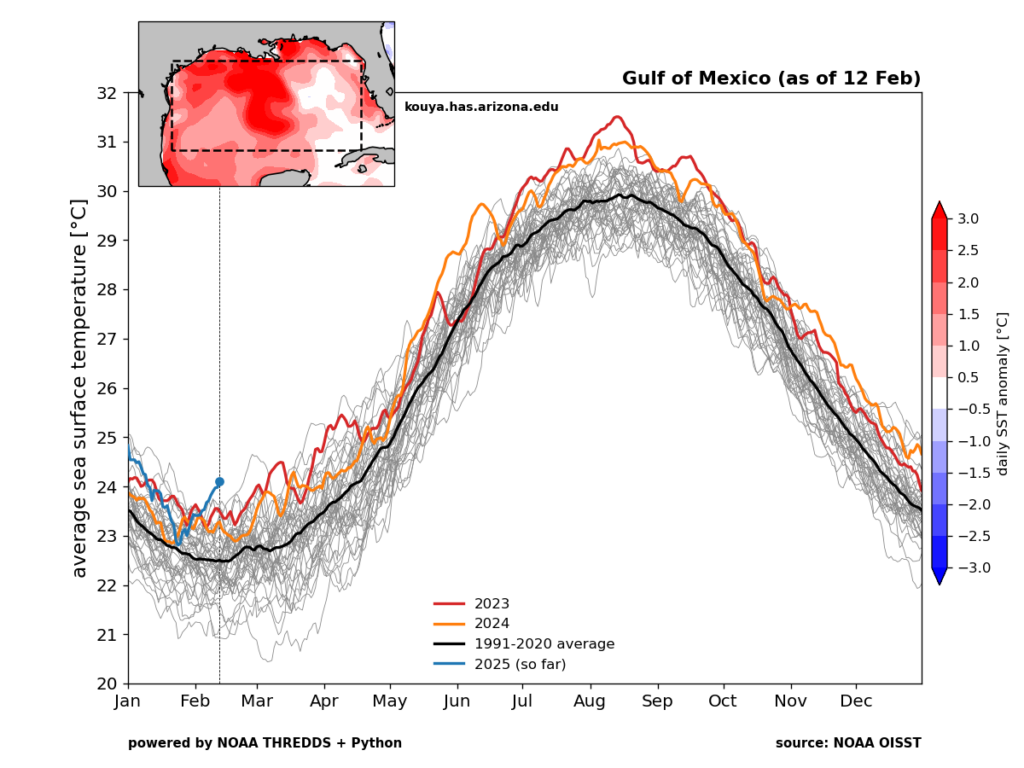

Storms like this with such a potent push of cold air require a balancing act to come to fruition on the East Coast in particular. If one of the pieces of the puzzle doesn’t time itself perfectly, the whole thing can shift markedly in one direction or another. In this case, the storm didn’t disappear, it just gets going too far southeast and offshore to make much difference. Suppression is the word we often use, and the whole mess got suppressed to the southeast. And thus, your snow forecast maps reflect the change in ways that will disappoint many winter lovers in DC or Philadelphia or my former stomping grounds of South Jersey.

In fact, this whole mess gets so suppressed that even as the storm comes northeast, it passes far enough off the coast of Canada to even avoid impacts in the Maritimes. Now, notably, the 7 to 13 inch forecast for Norfolk is actually quite impressive. If the high end of that range were to verify, it would be a top ten storm for the Tidewater and the biggest since 2010. Most areas will not see more than 10 inches in all likelihood, but either way, this will be a healthy snowstorm for Hampton Roads.

Overall, this proves another lesson in treading carefully with all storms, especially winter ones. This is one reason why the NWS usually doesn’t provide snow forecast maps more than 3 days in advance of winter storms. Often times, so much changes so erratically in that day 3 to 7 timeframe that those maps have little real value. Sharing speculation may be fun, but it won’t really give you a better reputation as a forecaster.