I wasn’t quite sure where to go with this post, but we’re a weather blog, entrusted by a lot of people to give “to the point,” hype-free information. And we’d be remiss if we didn’t at least chime in on what’s happening out West. It’s tough to watch what has been happening in California without some sort of visceral reaction. This doesn’t feel right. It isn’t normal. This is our new reality.

What is “normal,” anyway?

But it’s important to step back and look at what has happened in California and try to understand it and try to make sense of living with risk. California has a climatological normal, apparently. There is a “normal” value of rain or snow or temperature in California. But that normal is really just taking years of extremes and averaging them together. The normal in California is and has always been extreme. A former colleague of mine used to describe “average” by using the analogy of the river being 4 feet deep across “on average.” Which is to say, at some points, that river may be 20 feet deep. At others, barely six inches deep. In that sense, California has average or normal weather.

Is a winter fire season “normal” in California? Not really. But it’s not unheard of either. The front page of the L.A. Times is below from December 28, 1956. This was a rough wildfire episode in the Santa Monica Mountains.

From that December 28th, 1956 edition, “Wind, humidity, drought, and other factors have combined to make the Santa Monica Mountains fire almost impossible to combat with usual methods, firemen reported yesterday.” Further, “existing firebreaks are simply jumped by spot fires which pop up 100 feet and more from the main mass of flame.” Does this sound familiar? It’s important to understand these things so we don’t lose sight of the fact that just because perhaps there were a number of years where something didn’t happen, it probably wasn’t more than dumb luck. Fires in the dead of winter, while uncommon, can, do, and have historically happened.

It also brings me to a challenging, difficult point to make. Let’s be clear: Climate change is real, and it is making fires burn hotter, more intense, and more frequently in these traditionally more typical offseason periods. Would we have seen the type and intensity of fires we see today under the exact same weather conditions in 1956? Probably not. But climate change is not at all the sole “cause” of these fires being as bad as they are. The reality is always nuanced and difficult and messy. We’re not going to get into all the reasons here but vegetation management? Kind of important! Political decision-making? Important. Water supply constraints and infrastructure? Important. Population growth and sprawl? Important. Regulations and required environmental reviews? Important.

Climate change? Important. It’s all important, but to box it in as one issue, neat, tidy, and clean is a misnomer. And as disaster expert Samantha Montano put it “if you minimize the cause to just climate, you prevent us from being able to address the full spectrum of causes.” (emphasis mine)

All this to say that despite some of the obvious reasons like climate and population growth that have led to fires worsening in California, it remains an extremely complex issue with complex causes that are not singular or simple to solve.

What set this event apart?

So what made this specific event so bad? Let’s start with the fundamental problem: Drought.

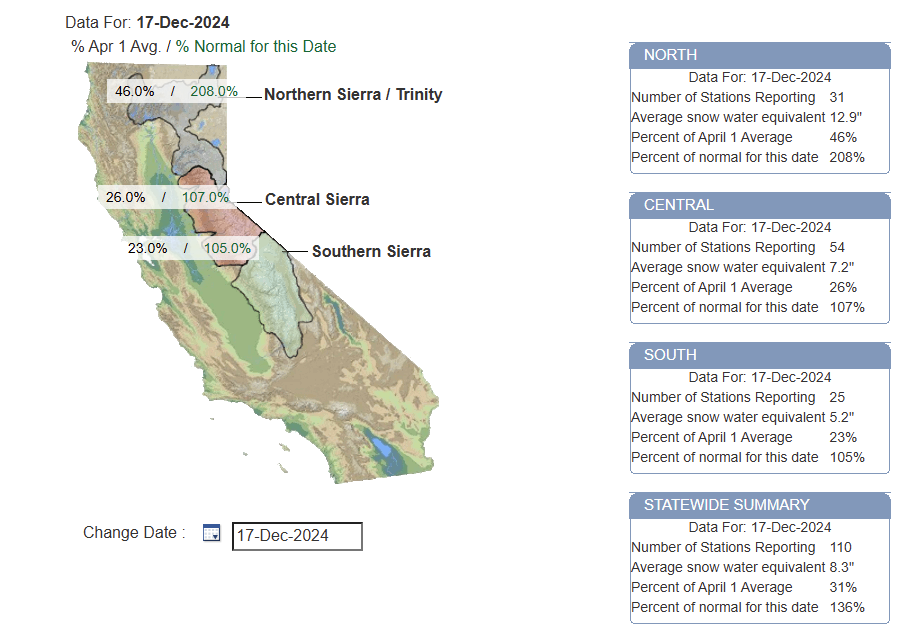

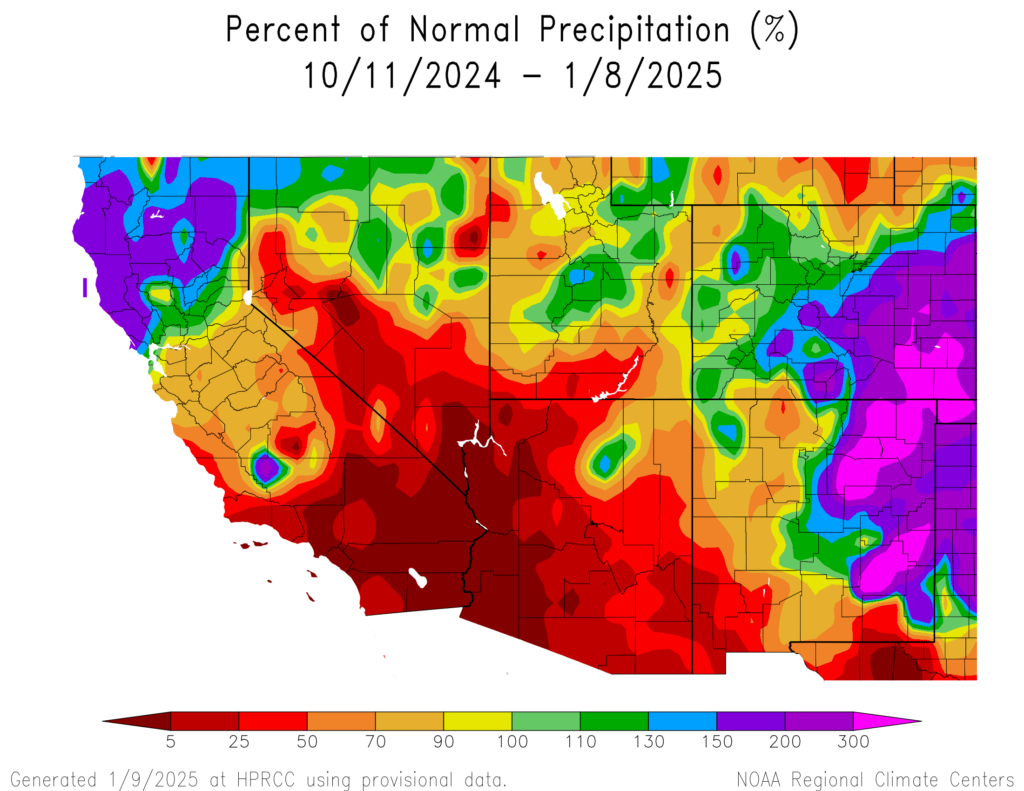

This winter has been borderline ridiculous in terms of how split the difference is in regime between northern California and southern California. San Francisco is sitting at 10.39″ of rain downtown for the season, compared to a normal of 9.44″ to this point. That’s about 110 percent of normal. Downtown Los Angeles? 0.16″ of rain so far this season, compared to an average of 4.76″ typically. That’s about 3.3 percent of normal. Southern California has had absolutely nothing this winter so far. Things have dried out, and there have already been two or three decent Santa Ana wind events to help exacerbate the drying out of fuels in this region. In other words, this is about as bad a scenario as you could ask for without any external triggers.

Unfortunately, the external trigger came on Monday and Tuesday in the form of strong Santa Ana winds.

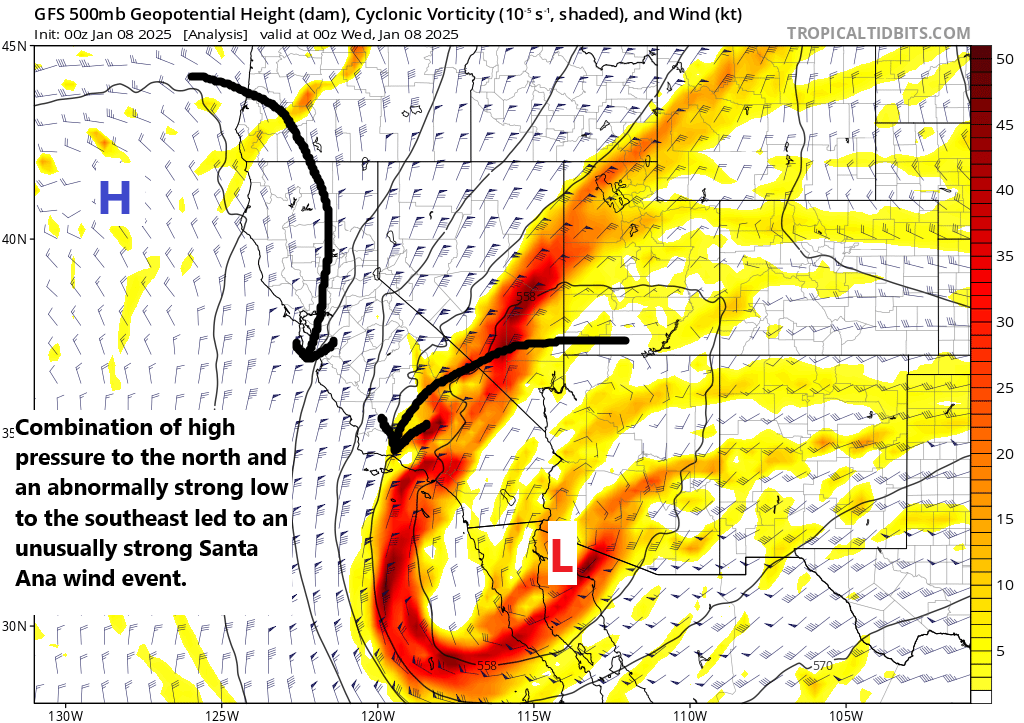

Winds gusted as high as 100 mph in the mountains above Altadena (where the Eaton fire impacted), in the 80s above Malibu, and in the 60s in many other areas. These were unusually strong winds by Santa Ana standards, likely exacerbated by what we call mountain waves. As winds from the north hit the east-west oriented San Gabriel Mountains, the winds are forced up over the mountain and then thrust down into the populous valley below. A lot of times, you’ll see more of a northeast type wind usher in the Santa Anas, with typical isolated pockets of strong winds. But when you get this level of north push, you can basically create a standing wave over the mountain which just leads to constant wind being pushed down below. While the Santa Anas typically come with strong winds, events like this in these specific areas are somewhat rarer, particularly having such a strong storm as was setup over Baja. And it was exceptionally well forecast ahead of time, which is why dire warnings were issued days in advance of this happening.

As these winds get forced downward, through the high deserts, then down mountains to the coastal plain, the air dries out further as well, which is why you end up with such a perfect recipe for fire danger in these wind events.

Will it get any better?

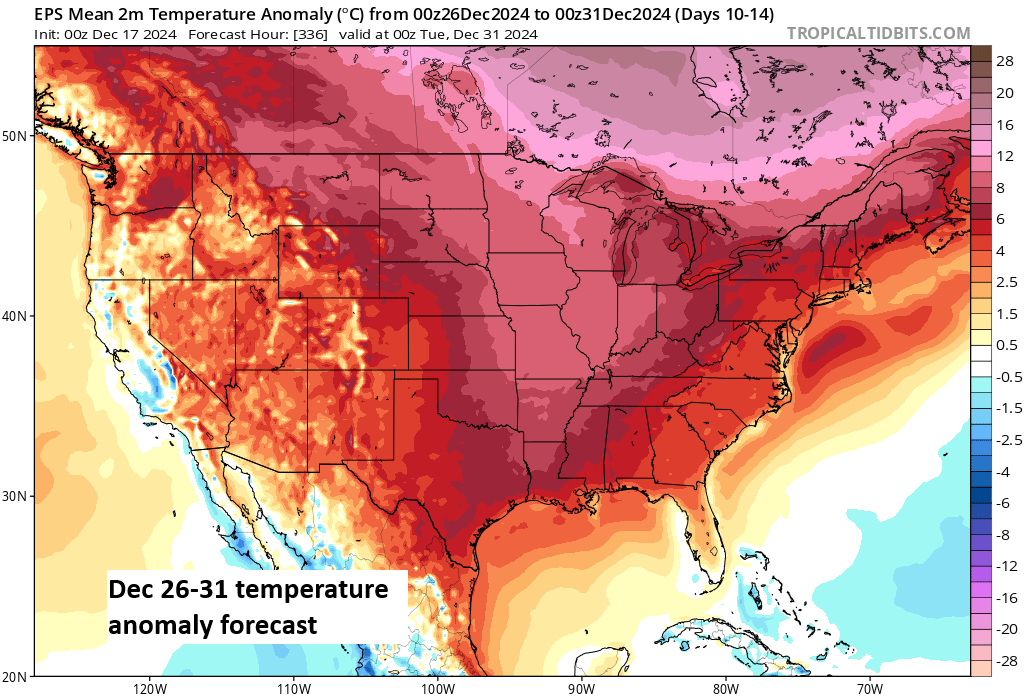

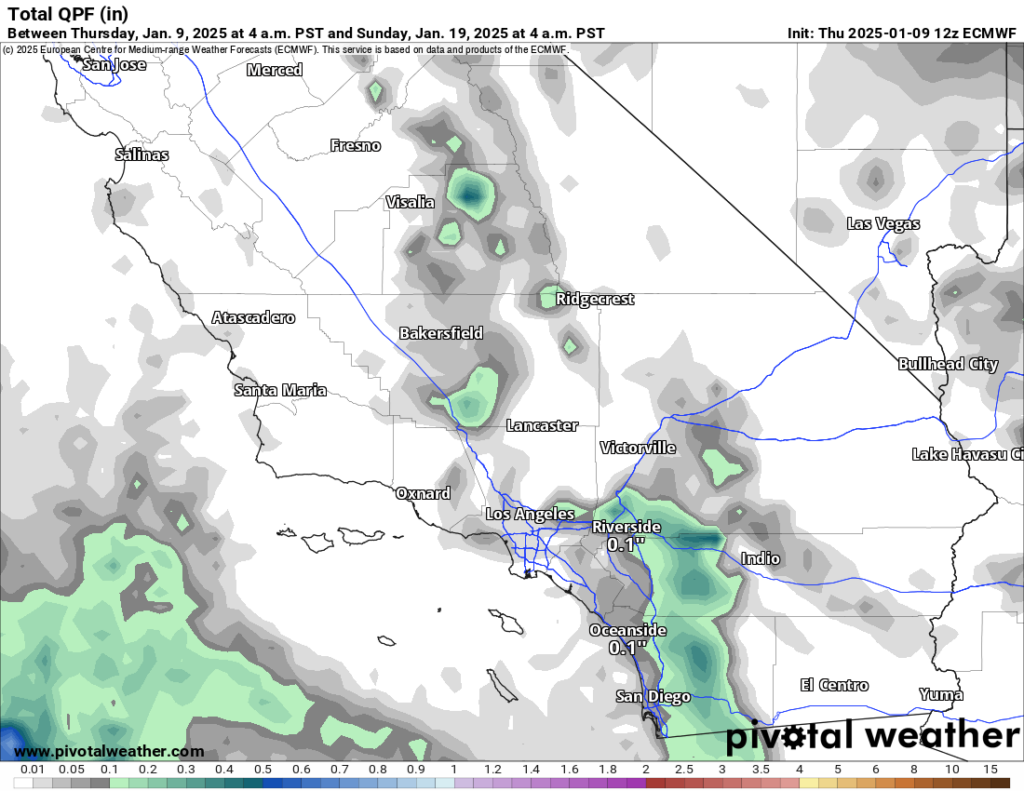

The short answer is not really. If anything, there will be continued offshore winds and fire risk as additional cold air gets pushed east of the Continental Divide next week. This likely means another period of borderline critical fire danger in SoCal next Monday and Tuesday. Rainfall over the next 10 days from the European operational model looks paltry at best.

Winter precipitation patterns can change in a hurry on the West Coast, and obviously the major scarring from these fires means that there will be a major sensitivity to heavy rainfall if and when it does occur again. Be it this year or next year. So, this area will not see dry conditions improve over the next week or two in all likelihood. Let’s just hope that forthcoming offshore wind events lack much bite.