One-sentence summary

With early hurricane season commentary beginning to emerge, we take a look at what is known here in late February.

Tropical aggression

Yesterday, AccuWeather, the private forecasting company from State College, PA published an article expressing concern for the upcoming hurricane season, using words like “super charged” and “blockbuster.” I’m not writing today to dunk on AccuWeather. I personally know a number of folks that work there, several of whom I would consider friends of mine. But I want folks to understand both the realities and limitations of hurricane forecasting in February.

About a month ago, we posted an article in which we shared some commentary about the upcoming hurricane season. In it, I wrote that “the combination of warm water and a weakening El Niño probably suggests an active hurricane season ahead in 2024.” I also noted that you’d probably be seeing some aggressive seasonal outlooks. Consider that article from AccuWeather to be a first or second volley. It’s important to note a couple things though. As is often the case, it’s the buzzwords that grab people’s attention and leads to accusations of hype in some circles. But the content of their actual article is fundamentally sound! There is one element I take issue with, and that’s their description of the Texas coast being at higher risk than usual for the upcoming season.

Forecasting landfall patterns consistently this far ahead of time is really, really hard. I’ve never found anyone that has done it successfully and at a consistent level. Anyone can claim they nailed a seasonal call this far out, but they’ve probably also had 50 false alarms to go with their handful of victories. Colorado State University, which releases a highly anticipated outlook each season has actually put their verification metrics online, and they did well this past season. But while they offer a landfall probability table by state, they are intentionally broad in their discussion, because specifically narrowing down a section of, say, a state’s coastline being at higher risk than another is difficult. If Texas is at higher risk, does that mean Louisiana is not? What of Mexico? At what point does “higher risk” kick in?

I don’t want to fault anyone or say I am against seasonal forecasts. I am not. But we have to be extremely careful how specific we get in February. The peak of hurricane season is still about six and a half months away.

So where do we stand now?

If you read last month’s post, the general takeaway was that there was no reason to forecast anything other than an active hurricane season in 2024. How active and how bad was TBD. Has anything changed since then? Not really.

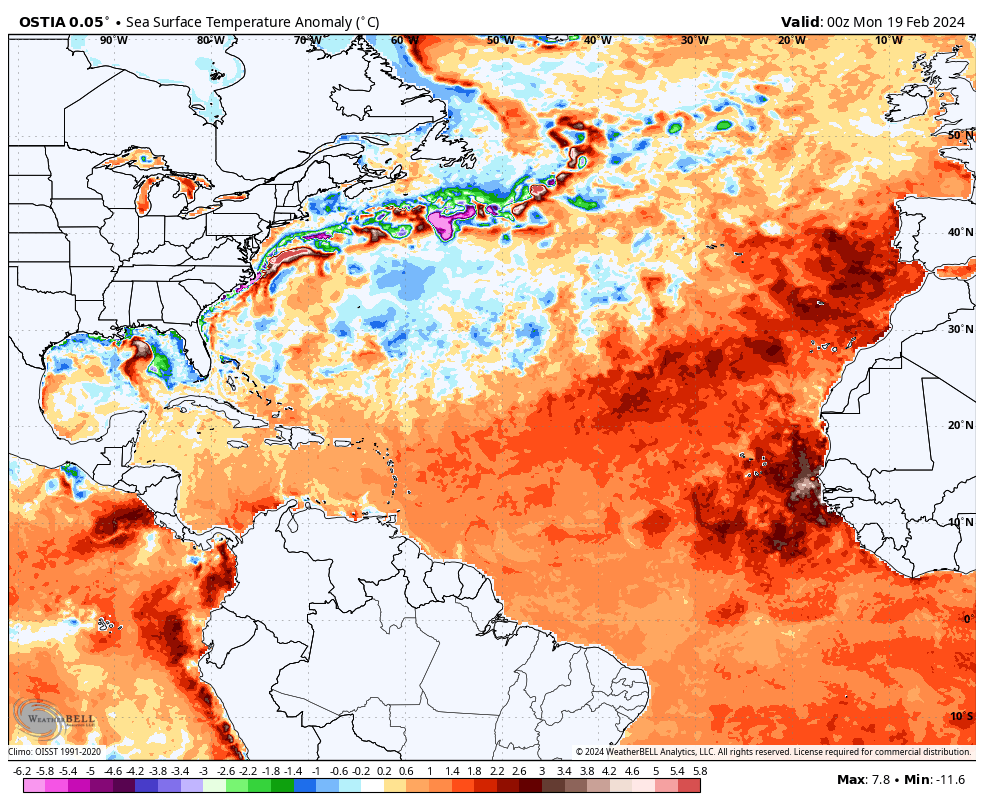

First, a look at sea surface temperatures (SSTs) shows that the Atlantic remains obscenely warm. Obscenely warm.

Seeing this in February is truly remarkable, as these readings, specifically in the Main Development Region are more normal for July. It’s February 21st, so a lot can change between now and June or July or August. But, suffice to say, this is as strong a signal for an active hurricane season as you would likely ever see. So, the SST checkbox is checked for “Active” for another month.

What about El Niño? Well, there are ample signs that it is beginning to wane as expected. The animation below shows SST anomalies from the Equatorial Pacific Ocean from the ocean surface (top) to 450 meters below the surface (bottom). Notice how a lot of the deep warm water, particularly on the right side of the image (the Eastern Pacific) gets eroded away in the last few frames. That’s a sign of colder water making a return to the ocean’s subsurface in the Pacific. It won’t take much to begin to wind down the El Niño from this point.

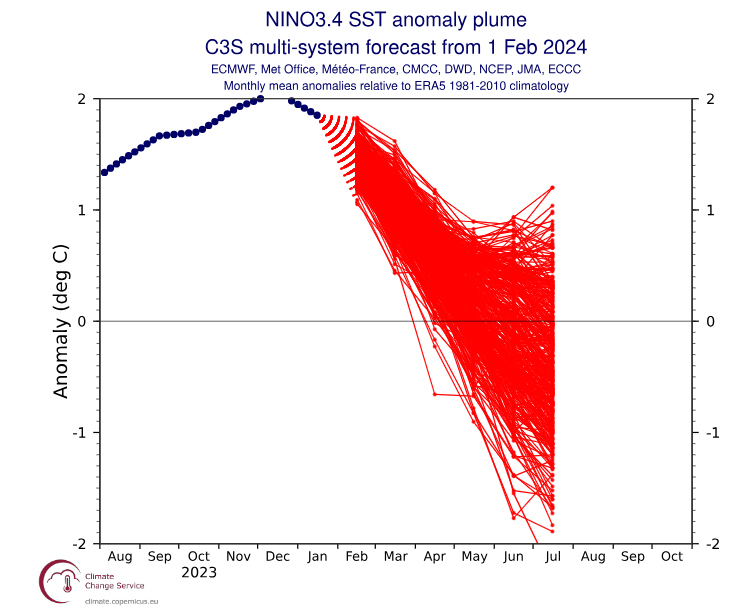

Again, it’s not uncommon for an El Niño as strong as this one to quickly weaken in springtime. And it appears this year will fit that trend. But where it goes from here is equally important in terms of how it may impact hurricane season. The latest long range forecast from a slew of government agencies shows about 2/3 of ensemble members taking us to La Niña by mid-summer and about 1/3 holding us back.

Ensemble forecasting is the best approach most times, especially at this timeframe because instead of one deterministic outcome, we get to see generally what the consensus is and where any reasonable subset of outliers exists. I look at these charts frequently, and a couple items stand out right now. First, the majority take us into La Niña by July, if not June. Second, some of these model members really take us into La Niña, perhaps moderately so by mid-summer. However, there is also a subset of members that pull a Lee Corso, trying to drift us back into El Niño after dragging us back to near neutral. The takeaway here is that the odds seem to favor La Niña, and indeed, NOAA did recently issue a La Niña Watch. But there is still some inherent uncertainty, and oh yeah, we are in what is termed the “spring predictability barrier,” which is a fascinating study in how models can be truly imperfect. I do think they’re getting better at this and perhaps this barrier isn’t as strong as it once was. But the stench of busted forecasts past does still linger in close enough proximity for me to proceed with caution.

So, the verdict? An exceptionally warm Atlantic Ocean, and odds favoring La Niña development this summer continue to suggest an active hurricane season ahead. But where those storms go, how strong they are, and when they’ll be at their worst is a forecast that is close to impossible to make at this juncture. As always, if you live in a hurricane-prone region, the best advice in any hurricane season is to be prepared as if that season were the one.

Does Houston experience more hurricanes during El Niño or La Niña?

THANK YOU for reiterating your earlier comments. I too started to read Accuweather forcast yesterday but about one paragraph in… I closed it, remembering your previous analysis. I do not understand why some forecasters like to sensationalize, over-hype and try to put the fear of God into our lives for something so far ahead and as you point out, very difficult to predict this far out. An “active hurricane season” is good enough and we will definitely stay tuned to your forecasts over any others. Keep up the wonderful job.

I agree about the unnecessary sensationalism, but it does one good thing – getting people to really prepare. I can see I might have to do a few things now besides hoarding water. I don’t know who said this but it works

“Pray for the best but prepare for the worst.”

Per Google: “AccuWeather Inc. is a private-sector American media company that provides commercial weather forecasting services worldwide.”

It’s not hard to understand: they provide consulting services to govt and business interests around the world that must plan their operations many months in advance. These firms look at broad trends and deliver a forecast to their clients based on what data is available. The same discussion came up around WeatherBell, also a commercial forecasting firm.

I was trying to understand the SSTs in the MDR & I came across something that said the Azores Hgh wasn’t as strong last year, and as a result, there was little wind, little mixing of water layers, so the surface waters just kind of cooked. The new SSTs reported (NOAA Climate Reanalyzer) for that region in Jan & Feb were as hot as typical July temperatures, so there’s been no cooling as far as I can tell. Just already hot waters primed to become hotter.

So, it looks like we’re (likely) walking into the season with a weak La Niña comparable to 2005 & 2020. Only this time there’s (01) very high SSTs, (02) increasing phenomena of rapid intensification since the 2010s, as well as (03) the storms not slowing down upon approach to land.

Last year we were protected by that relentless heat dome (in my opinion, at least), but I’m guessing that was associated with El Niño, which likely won’t be in place this summer.

Is there a place where GOM, BOC and Caribbean SSTs are reported and presented on a regular basis, like in a meaningful way to the common observer, with numbers on the chart instead of blobs (not intending disrespect)? Maybe after a certain point is reached, it doesn’t matter, but it would be empowering to at least have those numbers.

🌿 🌿 🌿

SCW is marvelous 💓 Tysm for everything you guys do. There is NO WAY I’d want to face the upcoming season without you. I’m so incredibly grateful for your presence.

🌬 ⚘⚘⚘

It’s nice to see a rational analysis without the hype that gives the impression someone is trying to sell us on something they don’t know for certain. I like the way you and Eric present the facts without the crystal ball forecasts.

A similar view of the ENSO spring predictability barrier can be found at https://www.worldclimateservice.com/2021/05/14/enso-spring-barrier/

Superb, fact-based discussion. And a great reminder to be prepared ahead of time. Being prepared helps to reduce panic.

Let’s go Blues!