At The Eyewall, we’ve focused on hurricanes and tropical storms since our launch in June. Some of you have asked what we’ll do during the offseason, and the answer is we will probably pull back our posts to every few days unless there’s a major weather event, and we will focus on extreme weather impacts in North America. We don’t want to offer clickbait or drama, but a forecast, an explanation, and context. I’ve decided to roll out something of that nature today with a focus on the Mississippi River salt water intrusion crisis in Louisiana.

One-sentence summary

The situation with salt water creeping up the Mississippi River in Louisiana is a complex one but one that has a basic solution (more rainfall) that does not look likely to be in the cards over the next 2 to 3 weeks in any meaningful capacity.

What is happening?

If you’ve been following the news lately, you may have heard about salt water creeping upriver in the Mississippi River in Louisiana. In the most simple terms, as dry weather has led to low river flows in much of the Mississippi Valley, denser salt water has been able to creep north at the bottom of the river. This isn’t unprecedented, but it isn’t common either. This happened to a much lesser extent last year and more notably back in 1988, when the salt water barrier shifted over 100 miles up the river west of New Orleans. This led to a couple days of salt water intrusion into New Orleans’ water supply which ended quickly.

WWNO, the NPR affiliate in New Orleans has a great rundown of what’s happening.

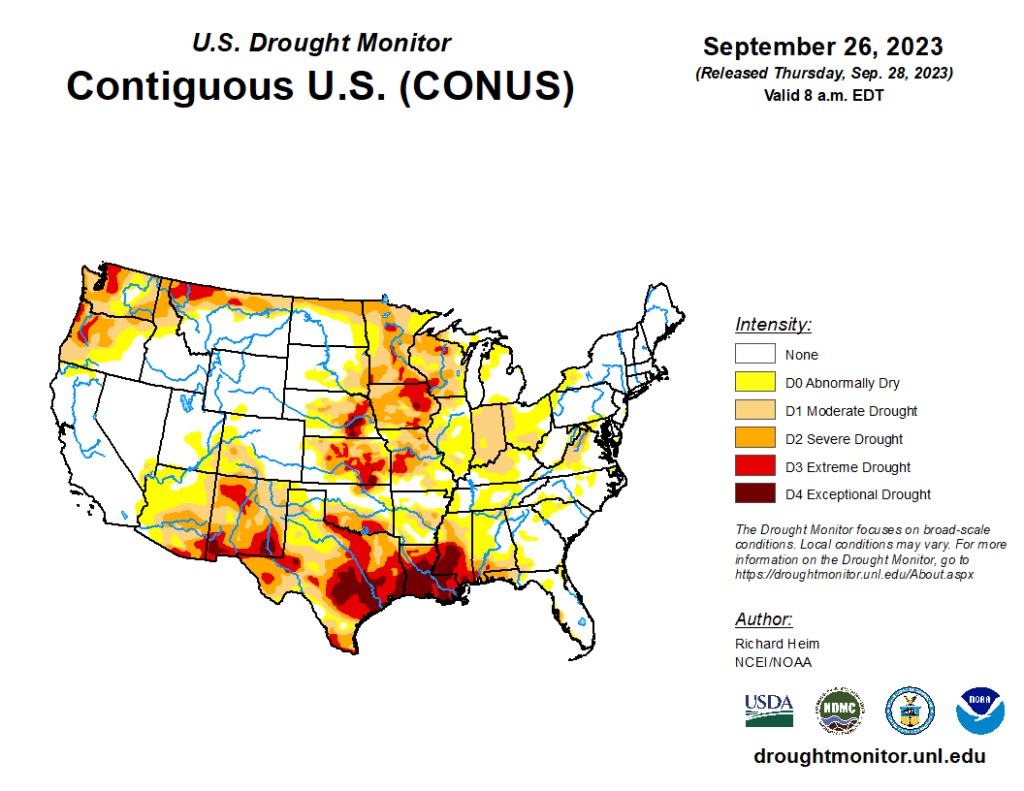

Virtually the entire Mississippi Valley is in drought right now, with a good chunk of the Missouri and Ohio River Valleys that feed the Lower Mississippi also in drought or abnormal dryness. The hot, dry summer in Louisiana in particular has exacerbated the dryness and drought there, with the entire southern two-thirds of the state in either exceptional or extreme drought.

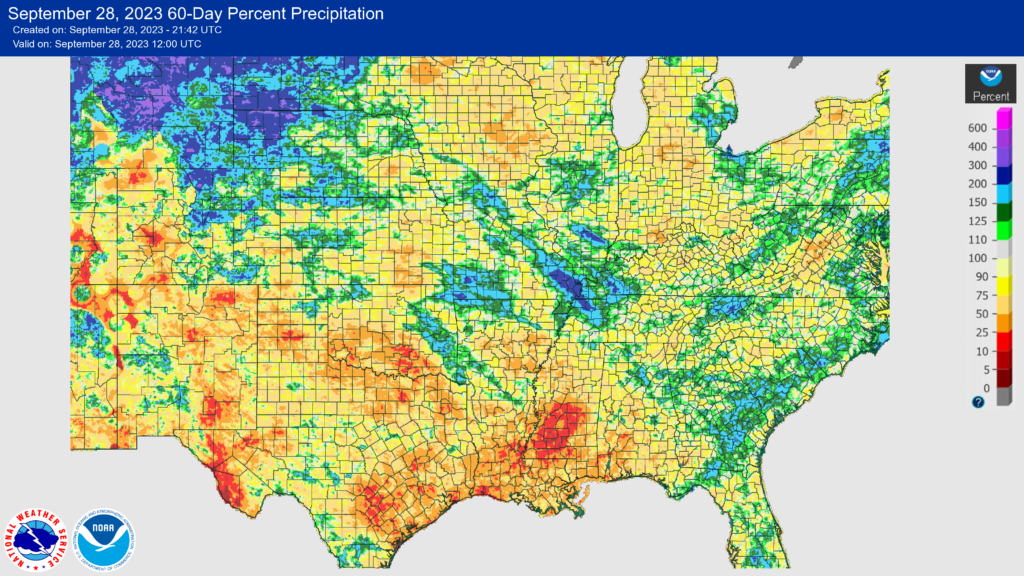

The last 60 days have seen 5 to 50 percent of normal rainfall along the Mississippi south of Memphis. The Ohio Valley and Missouri Valley have both seen 50 to 75 percent of normal rain. All this combined with the extreme drought in Louisiana has led to a confluence of problems and an expanding salt water wedge.

What is the rainfall outlook?

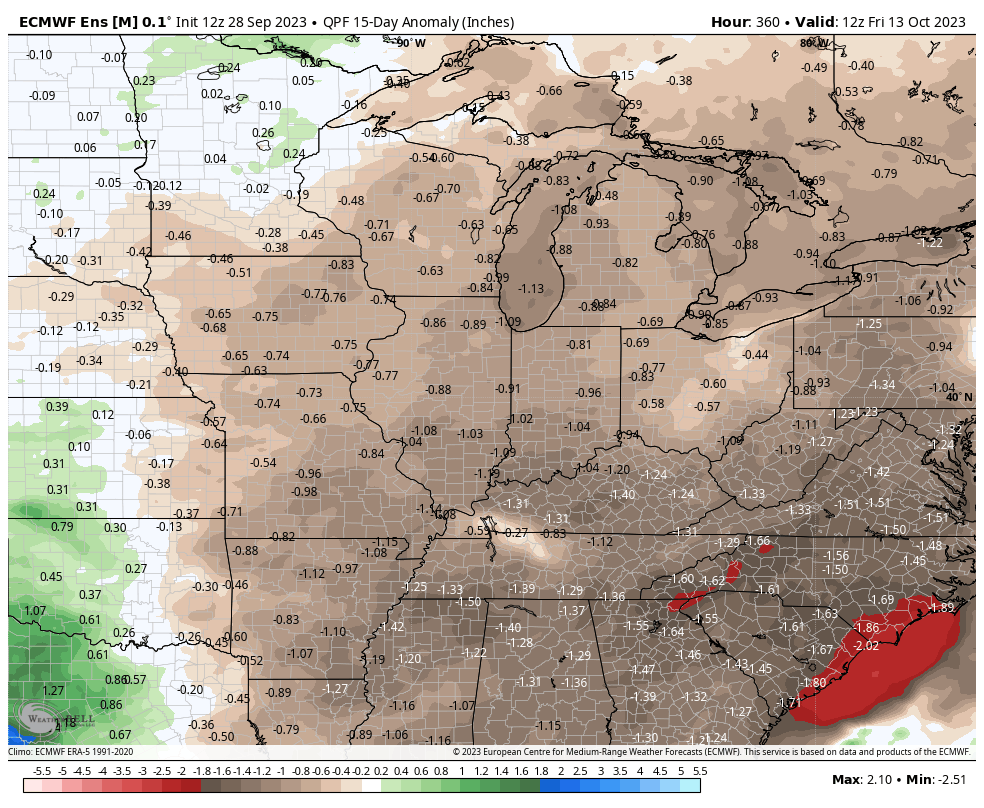

To solve this problem, the main thing you need is just simply rain. It needs to rain in the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi Valleys sooner than later. Is there anything in sight over the next two weeks? Not really. The Lower Mississippi Valley should see minimal relief. The Ohio Valley looks quite dry. The Missouri Valley and Upper Mississippi are more mixed, but we’re just not seeing signs of any appreciable rainfall over the next two weeks.

This is why you are seeing so much news about preparations for this in New Orleans and other Louisiana communities. Without meaningful rain over the next two weeks, you will continue to see the salt water migrate north. Current weather forecasts push us out to about mid-October and current projections for the wedge have it getting to New Orleans in later October. Even if 10 inches of rain fell over Memphis on October 15th, it would take some time for that water to flow downstream and get to New Orleans and southeast Louisiana. And isolated rain is not the answer. This problem requires a lot of upstream rain over a broad area. So it seems pretty clear that this problem is going to worsen.

So when can we expect a change? Well, when we look at the Climate Prediction Center’s outlook for weeks 3 and 4 (and granted, this is from last Friday), we can see signs of life in Texas or the Southern Plains, but probably nothing that would help “solve” the problems in Louisiana.

The CPC outlook for October is positive with a lean toward above normal rainfall in the mid-Mississippi Valley. I’m not sure if changes over the last week since this map’s release have necessarily lowered chances of this outcome, but I don’t believe they’ve helped much.

The bottom line: The situation with salt water in the Mississippi River is going to worsen in the coming weeks, and there is not necessarily any strong signal for changes in the rain patterns over the key areas required to alleviate the problem. We need to see a change in the rainfall chances in either or all of the Ohio, Mississippi, and Missouri River Valleys before we can be confident that some help will be on the way. And at least into mid-October and possibly late October, that’s not likely to occur.

Another example of the effects of climate disruption. Actually this emphasizes how precious fresh water is for our world. The lack of rainfall or severe torrential rain, which runs off too quickly, are problems everyone will have to face.

Here in Houston, we are losing water everyday due to water mains breaking. A solution is to bury the mains six to eight feet deeper. An expensive proposition nonetheless.

Is it? I won’t argue climate changes but its a bit disingenuous to attach a single event to some ominous sounding “climate disruption”. During the Dust Bowl era (1930’s) the saltwater wedge made its way inland nearly as far as it is now. Partial records from before also speak of the intrusion. Were these “climate disruption events”? For nearly every event being experience today there are historical records of nearly the same event taking place decades or centuries ago. In fact quite a few of our heat records that we broke this year took place in the early 1900’s.

I’m all for the science and possible intervention but we need to keep the rhetoric in check.

Anomalous climate and weather discussions like this (salt water intrusion in NOLA) as things occur through out the year is a great idea.

I had read about the salt water intrusion, but your explanation helped me understand it much better 🎯

The Eyewall is wonderful and I’d really like to see it year round – and if it wasn’t up, I’d feel something of a loss.

I have the feeling that a lot of us have a lot more confidence in understanding what’s going on with all this weather-related uncertainty with this site around. I know I do.

I have been quite concerned with the SSTs this year, and the unpleasant possibilities they pose, but I also feel I have a better handle on whatever pops up due to this site. The Eyewall has tremendous psychological value as well as weather-related information.

Thank you so much for all your work; it has come at a most needed time 😊

🌬⚘

Many thanks, Cat!

I was an engineering coop student for the (then) BP Refinery at mile marker 54 on the river in the summer of 1988. Every Wednesday they would give me a newspaper and I would plot river levels at points as far north as Memphis. When it rained you could see the fresh water plug coming. When it hit the intakes of the refinery they would pull in as much water as possible. During times of salt water the plant was using portable RO trailers to clarify the water for use. I think they had every potable RO trailer available in the region!

It’s crazy when you think about it…such a unique problem, and certainly emblematic of the risk you face at the coast. Hopefully lessons from 1988 will be applied here.

In a typical summer one or more tropical storms or hurricanes will make landfall on the gulf coast and then sweep north through the Mississippi River watershed dropping substantial rainfall. Is it possible that this lack of tropical storm activity in the Gulf, while preserving us from property destruction and disruption of our lives, has contributed to the low water levels in the Mississippi River? I wonder if there have been other effects, perhaps decreased runoff of agricultural residues into the Gulf.

I found this post really fascinating and look forward to more like it. It doesn’t directly affect me, but it is good to learn about things like this. I never heard of this before this article.