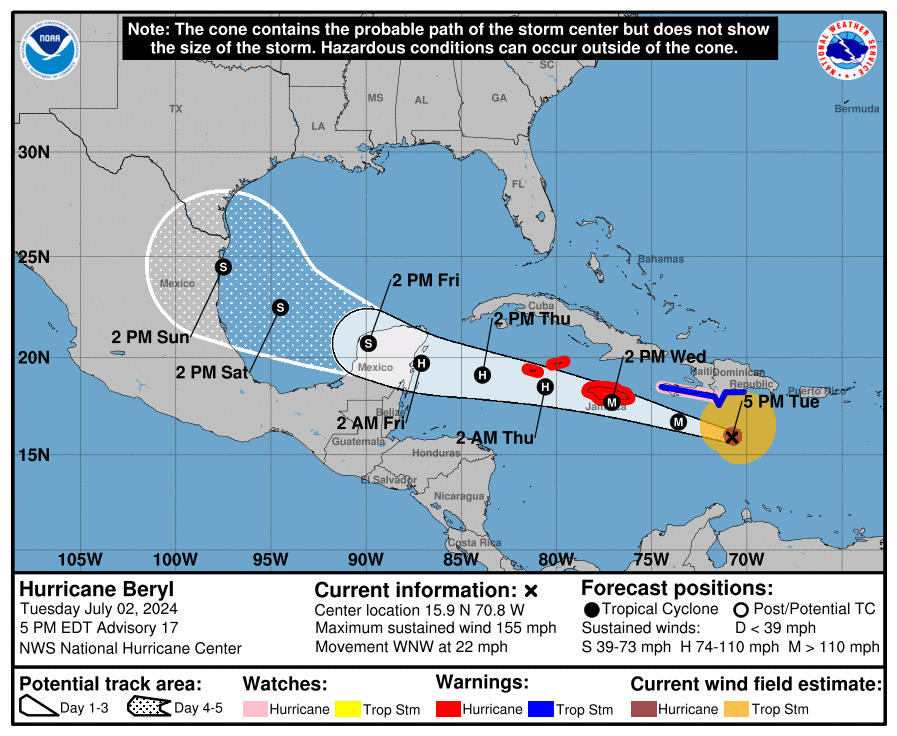

(5:30 PM CT update): Beryl is beginning to feel the shear as laid out in our post below, and it is now a category 4 storm with 155 mph winds. For folks in Jamaica, this offers modest comfort, as a major hurricane is going to make landfall (or come close) there tomorrow. Little has changed with respect to Jamaica and the Cayman Islands, so reference the post below on that.

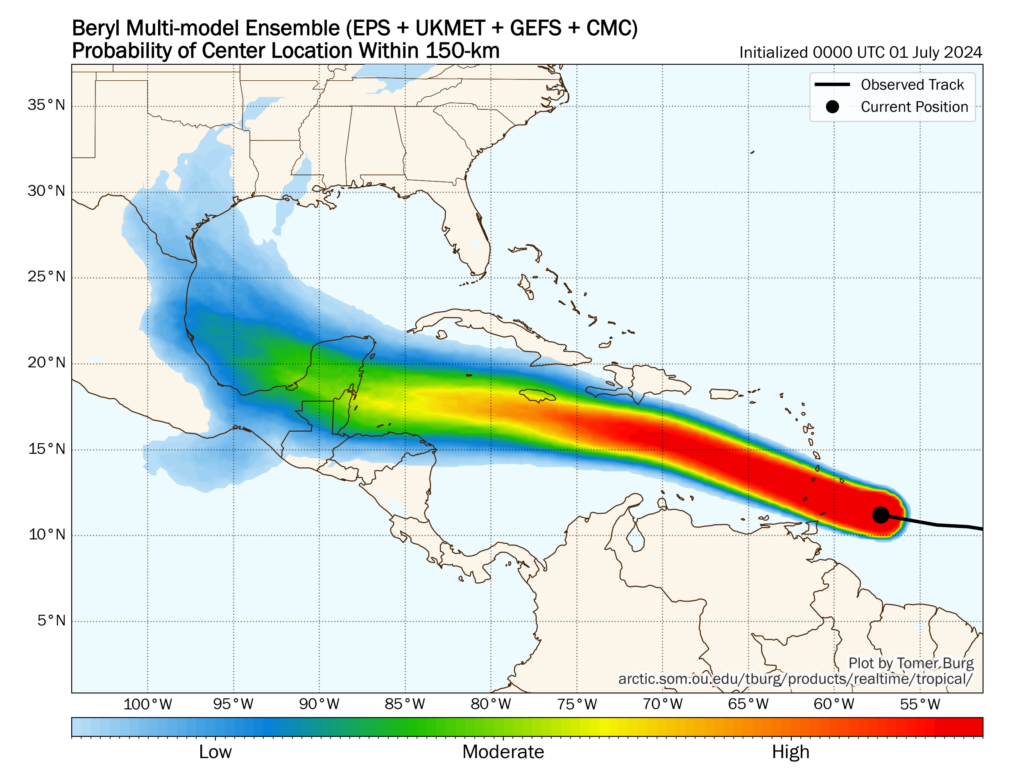

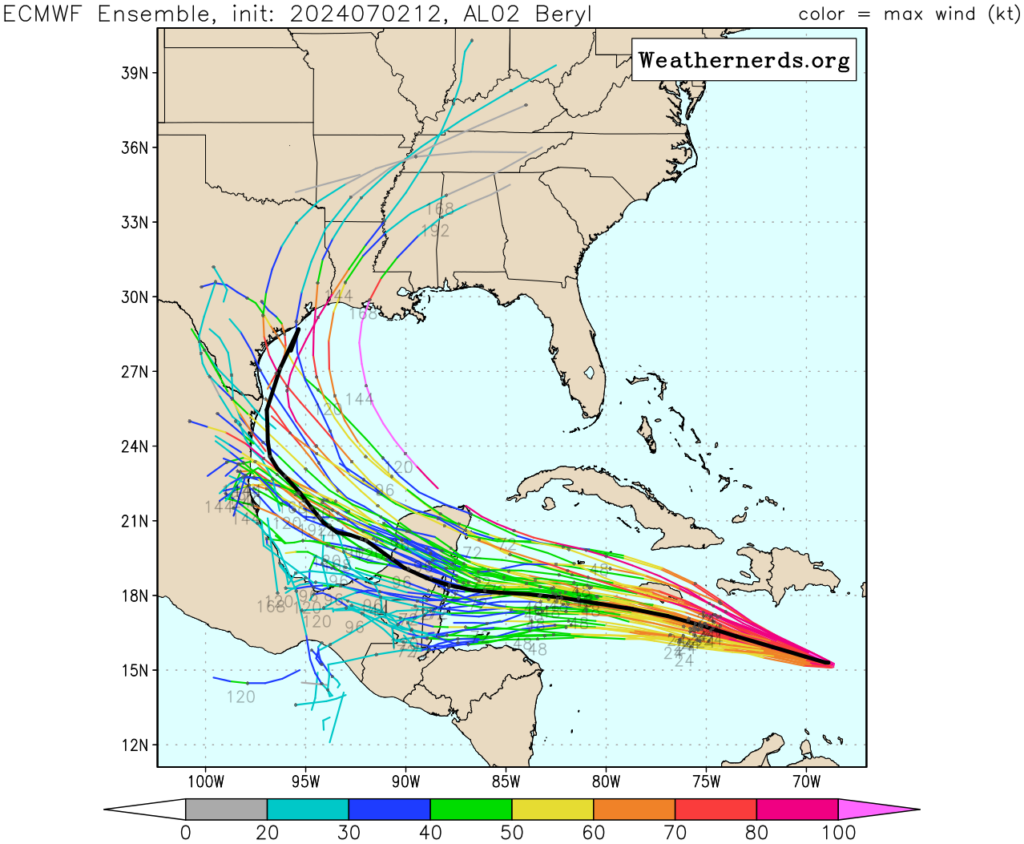

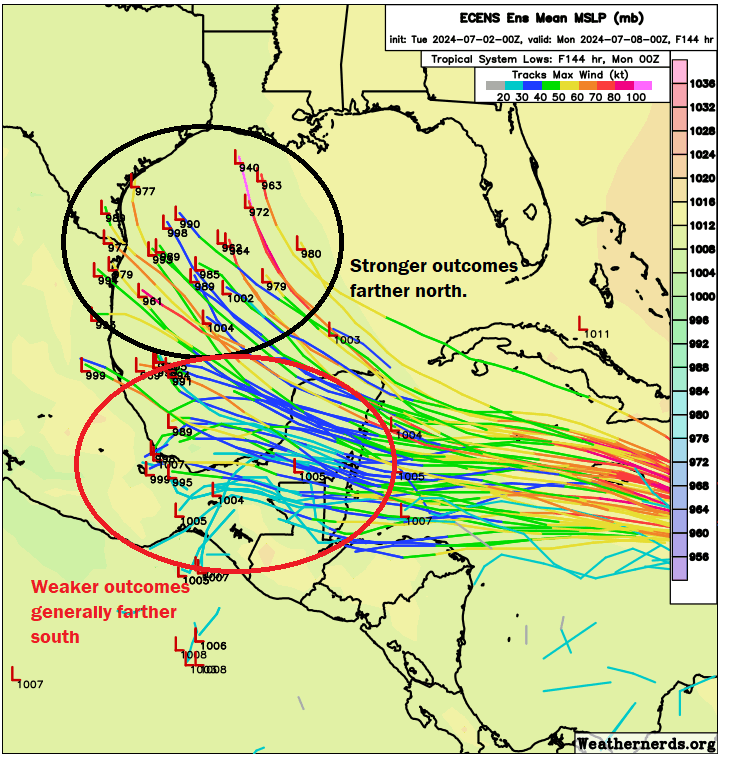

I need to say some words to people in Houston. We are getting blasted by a few of you for apparently underselling the real threat from Beryl. If you read the post below, we’ve taken a very down the middle, neutral stance on the storm, explaining how it is still likely to pass to the south, though if it were to not weaken as much as forecast over the next 36 hours, it could come a bit farther to the north. We even went so far as to show the European ensemble models with the distribution of some closer to southeast Texas and others in Mexico, and we explained how this could be and what to watch for. I’m not quite sure what isn’t resonating with some people, but those are the facts. Here is a look at today’s most recent European ensemble members, 51 of them:

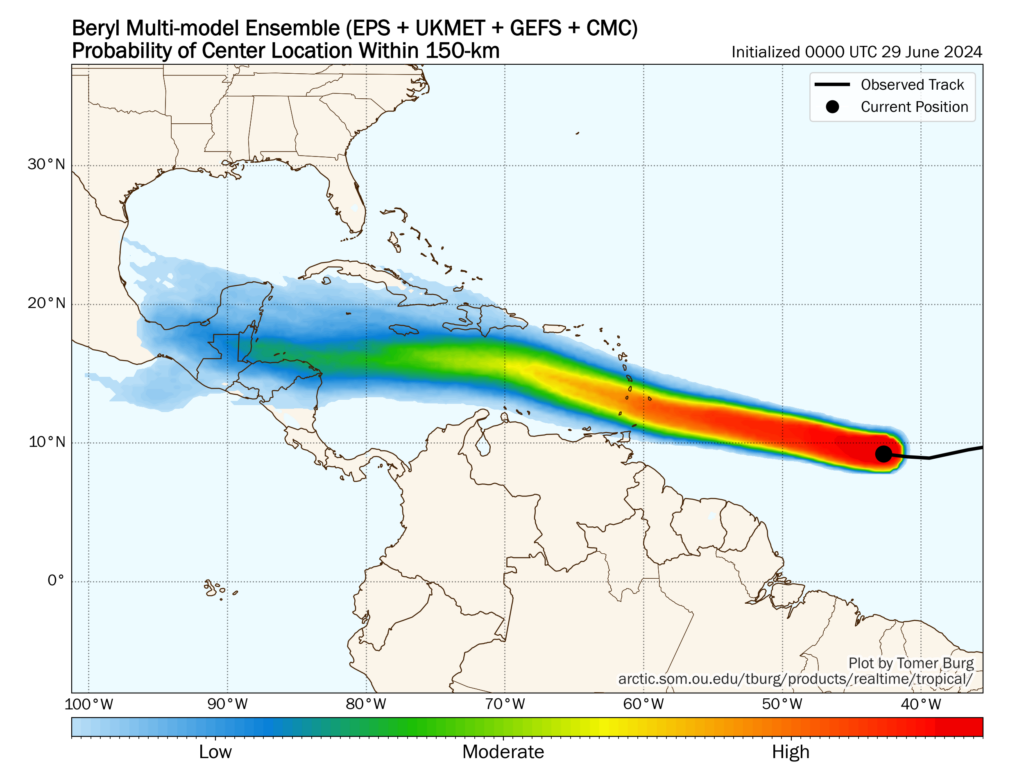

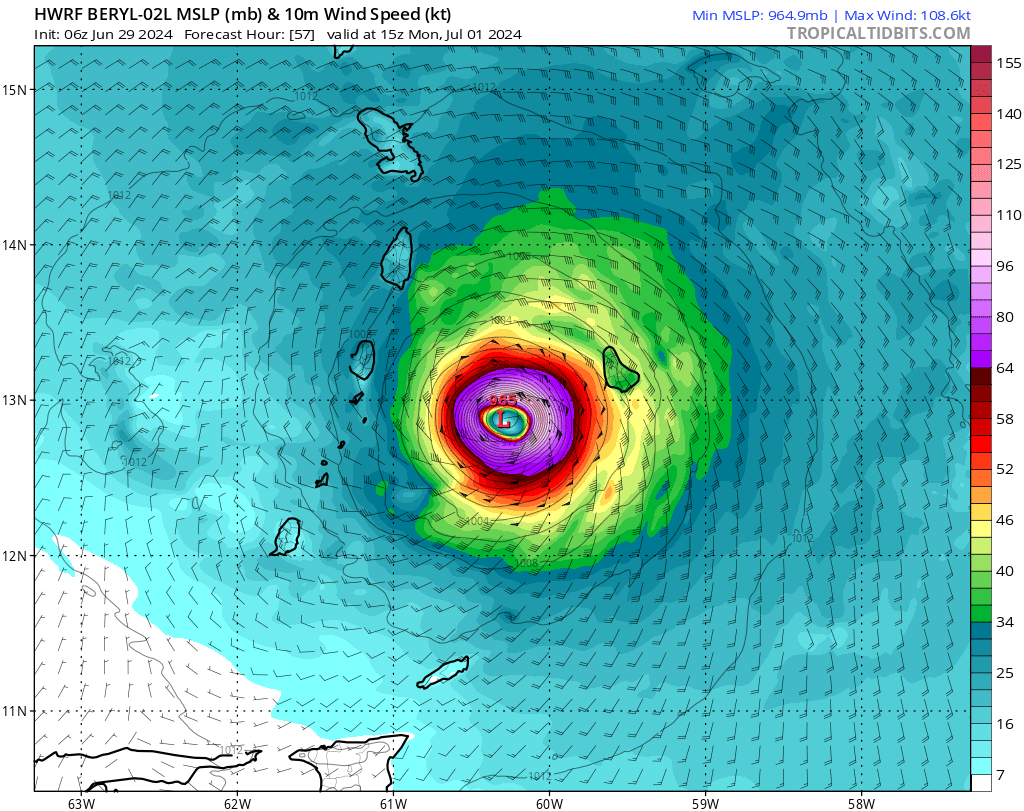

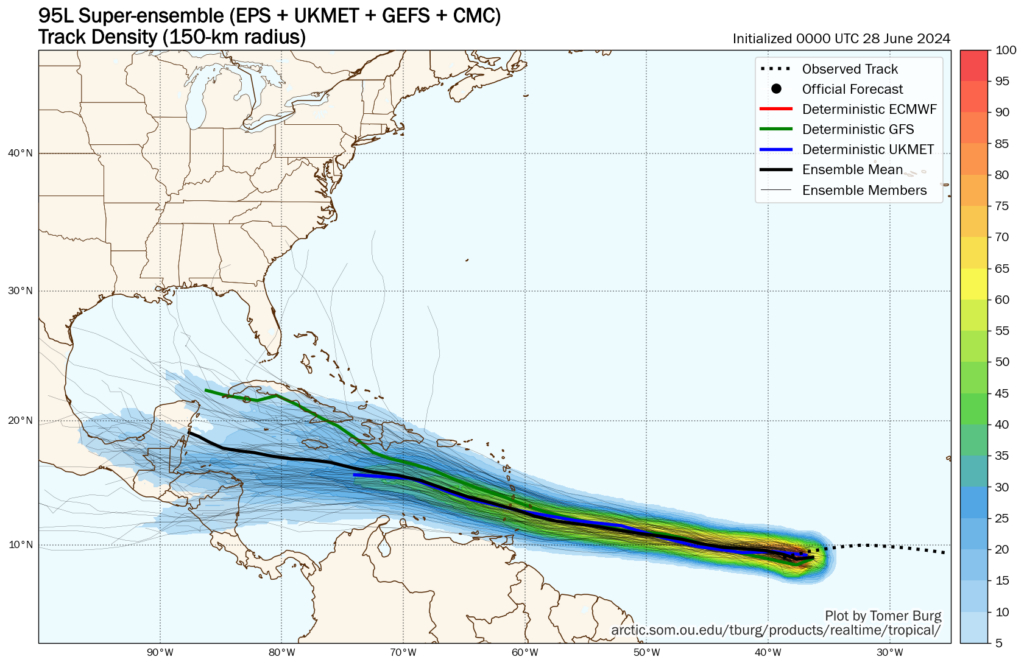

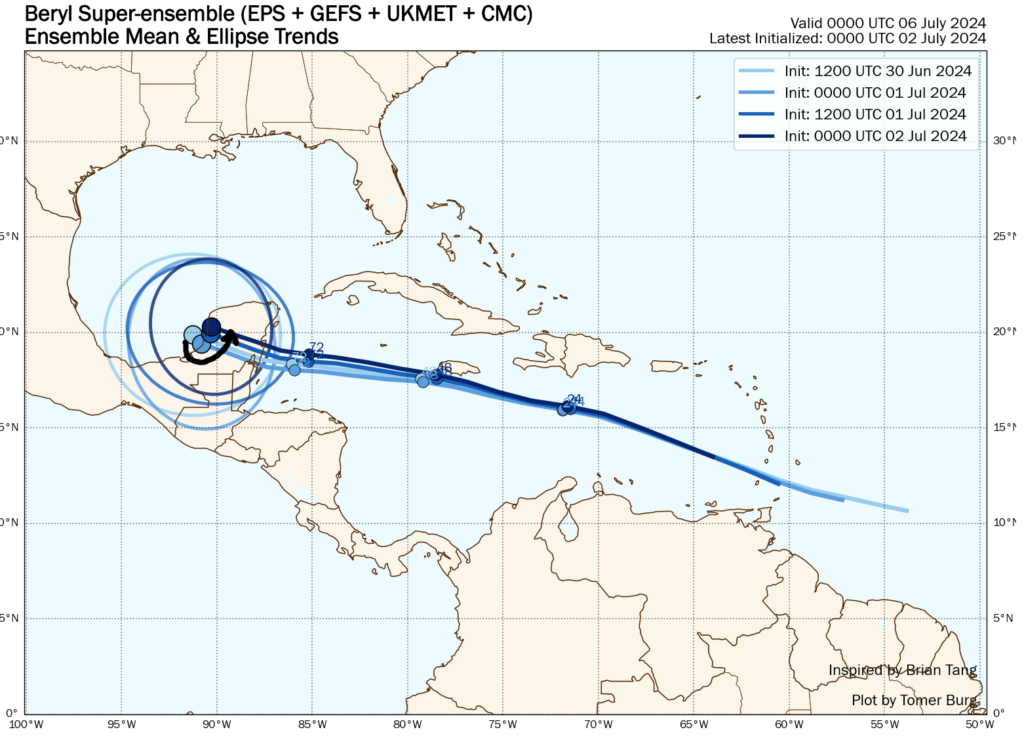

Of the 51 members, 5 of them or 9.8 percent bring Beryl into the Houston area or Louisiana. This is down from 8 earlier this morning. If you would rather the GFS Ensemble, 4 of the ensemble members, or about 13 percent bring it to Texas or Louisiana, the same as earlier. Roughly one tropical model (the HWRF) brings Beryl to Houston. The HWRF historically would handle a weakening tropical system poorly, so I would be apt to discount it in my weighting as a meteorologist with a number of years of experience tracking and forecasting these things.

I write all this to say: No one is saying to ignore Beryl. But, look, those statistics of objective model data imply that the risk to Houston remains…pretty low! Should we continue to watch this? Absolutely! And I laid out the case of how this could become more problematic in Texas below. So, let’s just take a breath and watch what happens over the next 24 to 36 hours.

Headlines

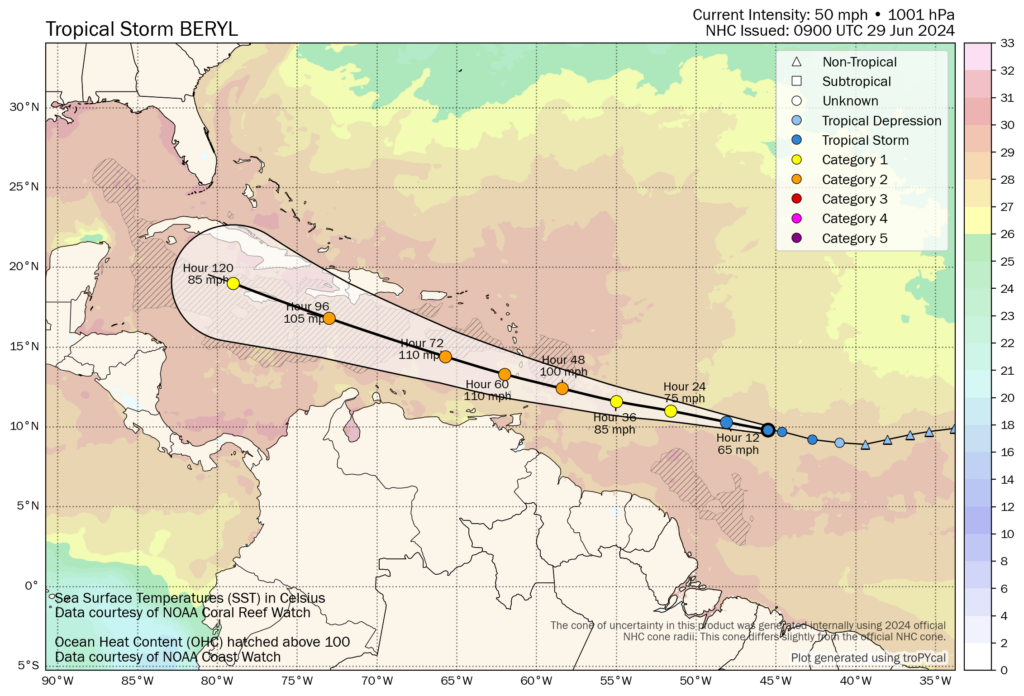

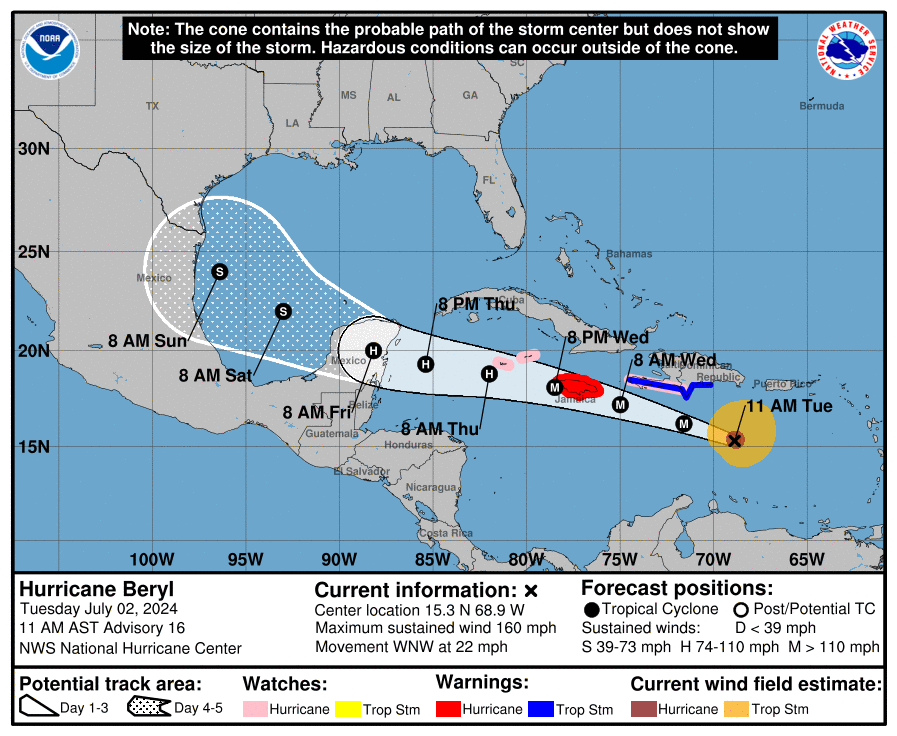

- Beryl remains a category 5 hurricane with 160 mph maximum sustained winds.

- Beryl is expected to make a direct hit on Jamaica tomorrow as a major hurricane.

- While Beryl is likely to weaken over the next 48 hours, it may not occur fast enough to drop under major hurricane intensity through Jamaica and possibly the Cayman Islands.

- Heavy rainfall and flooding are likely along and north of Beryl’s path in the Caribbean.

- Beryl’s forecast track remains dependent on a number of features as it comes west, but it has trended a little farther north today versus yesterday.

Hurricane Beryl (160 mph, WNW 22 mph)

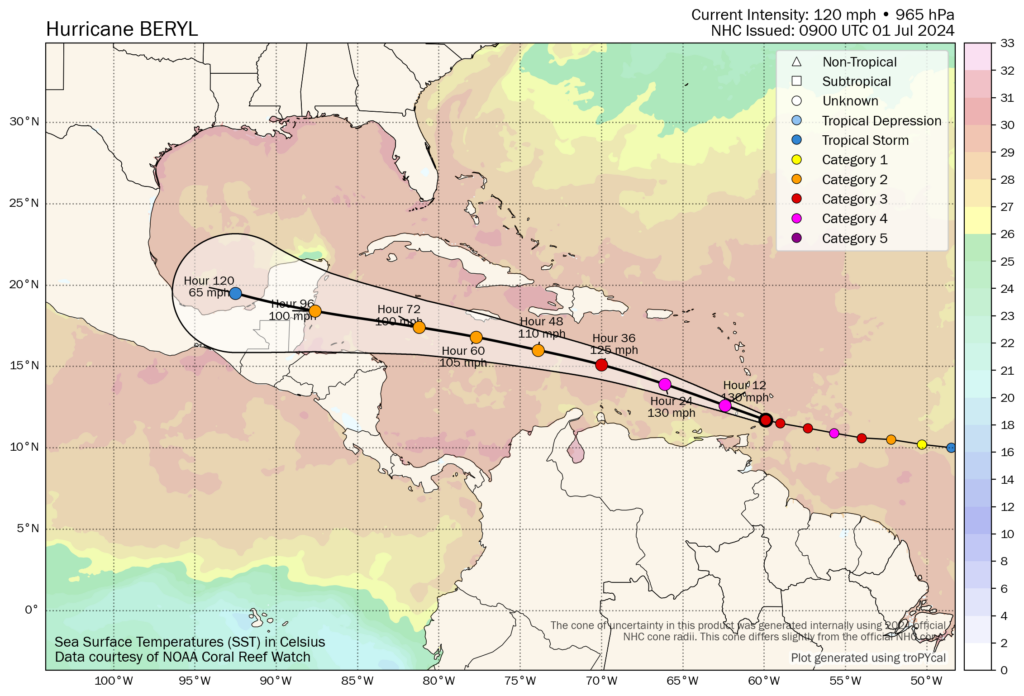

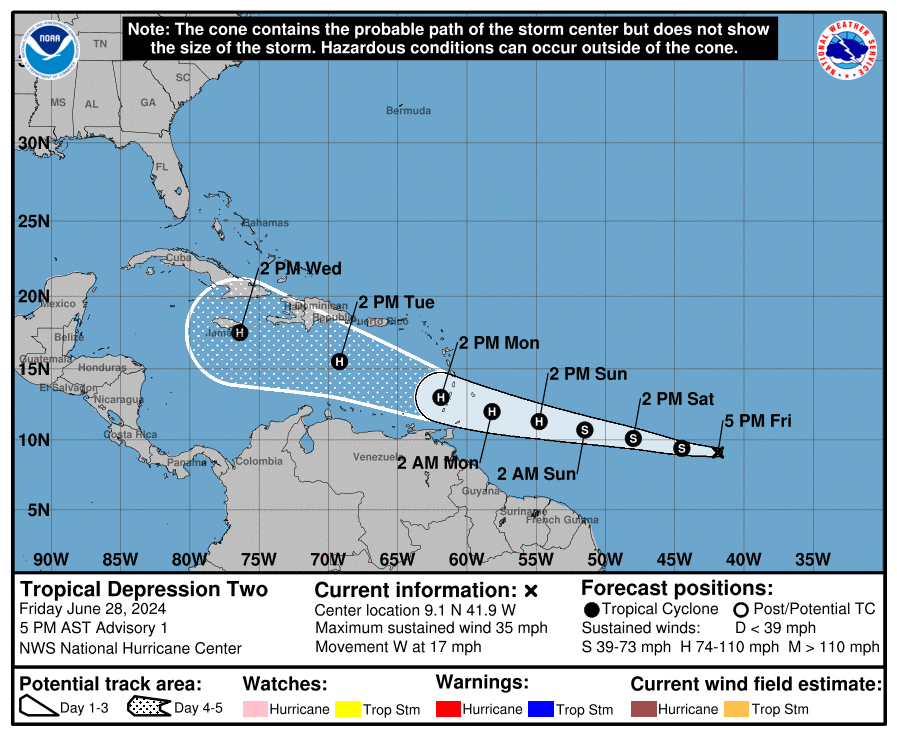

Hurricane Beryl somehow managed to continue strengthening last night and achieved category 5 status late in the evening over the eastern Caribbean. It has maintained that status today and has 160 mph maximum sustained winds as it races west northwest across the Caribbean.

Over the next 36 hours, Beryl will remain on a course that should bring it very, very close to a direct hit on Jamaica. At the least, it will be a close pass, and hurricane conditions are expected there beginning late tonight or tomorrow morning. Preparations for a major hurricane impact should be rushed to completion in Jamaica. Folks in the Cayman Islands will need to watch Beryl closely as well as it passes near or just south of there tomorrow night.

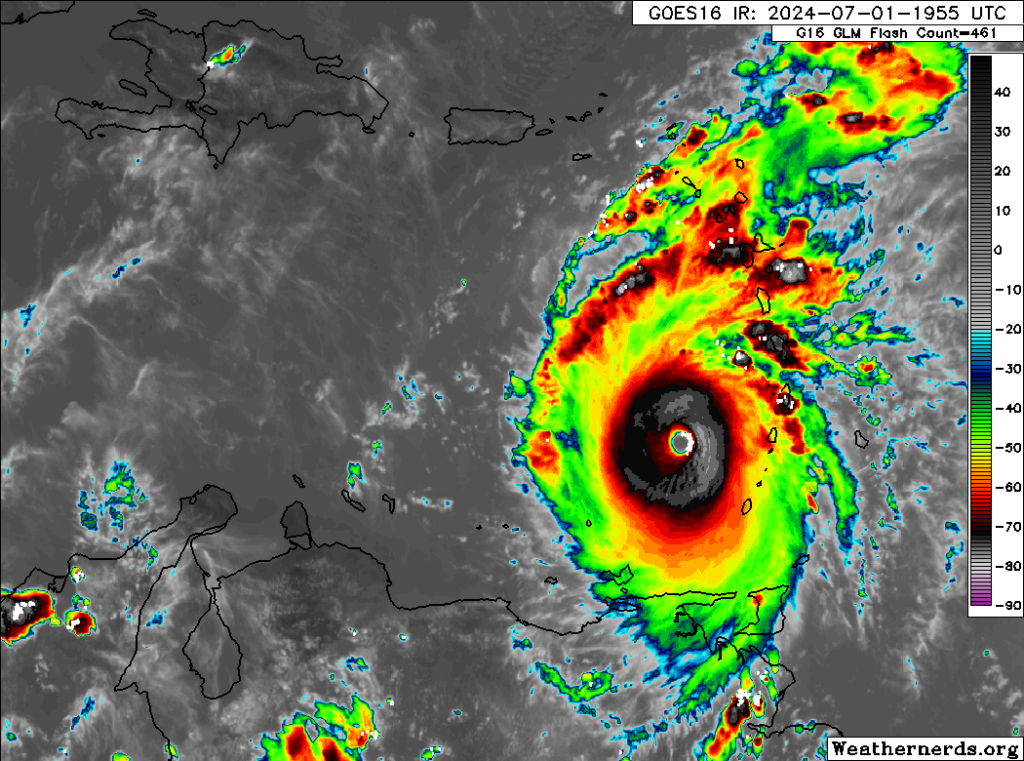

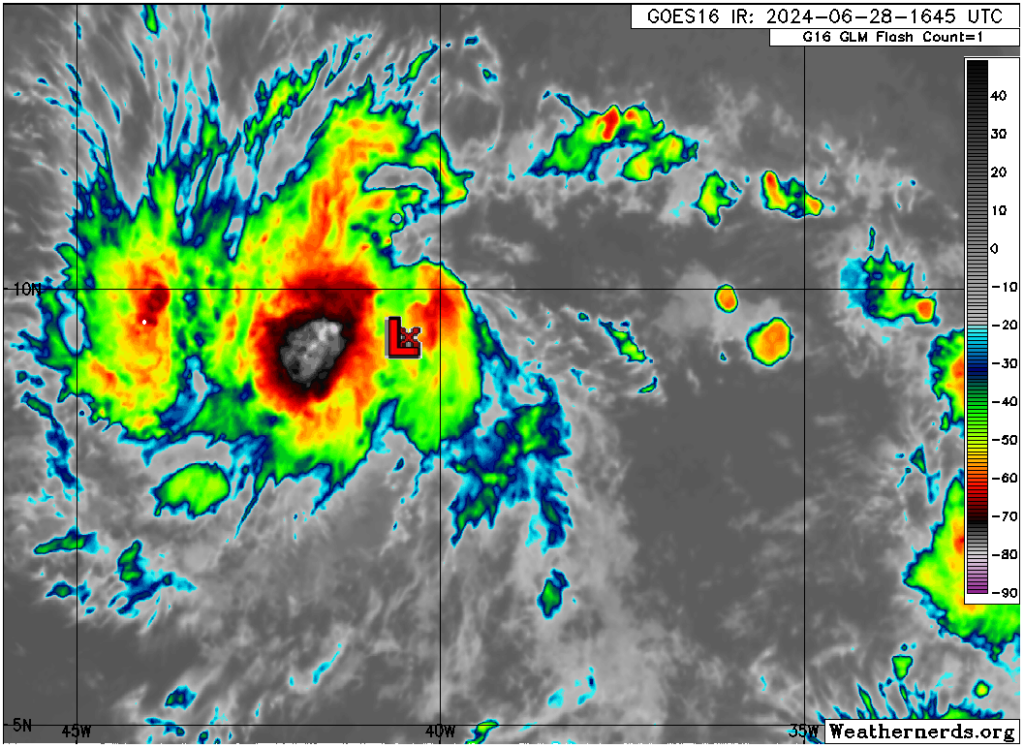

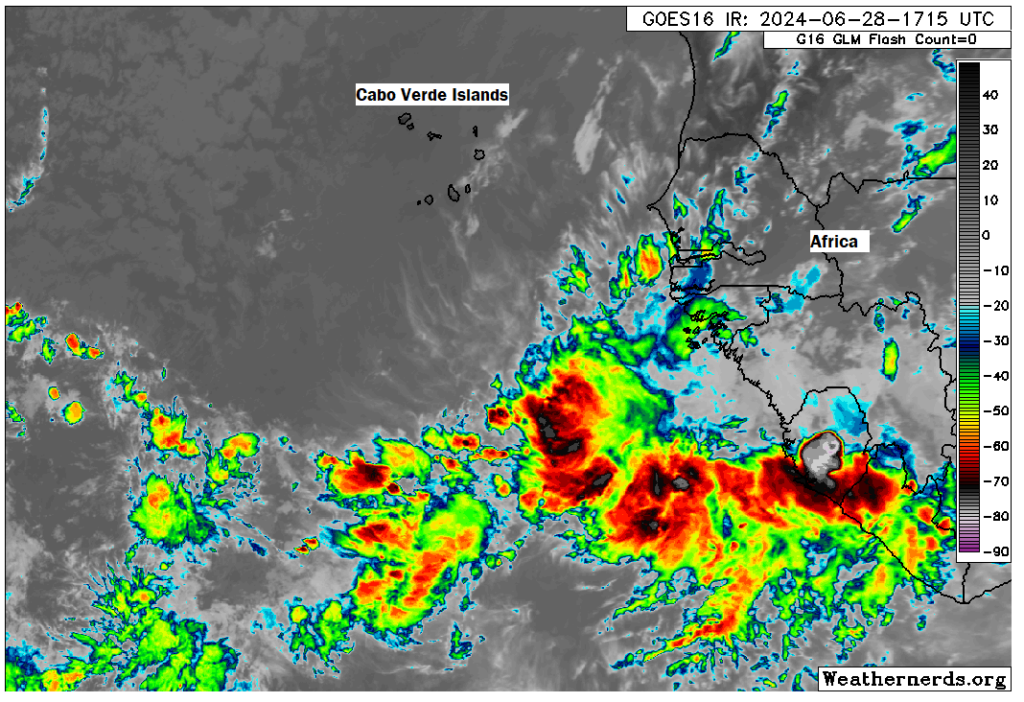

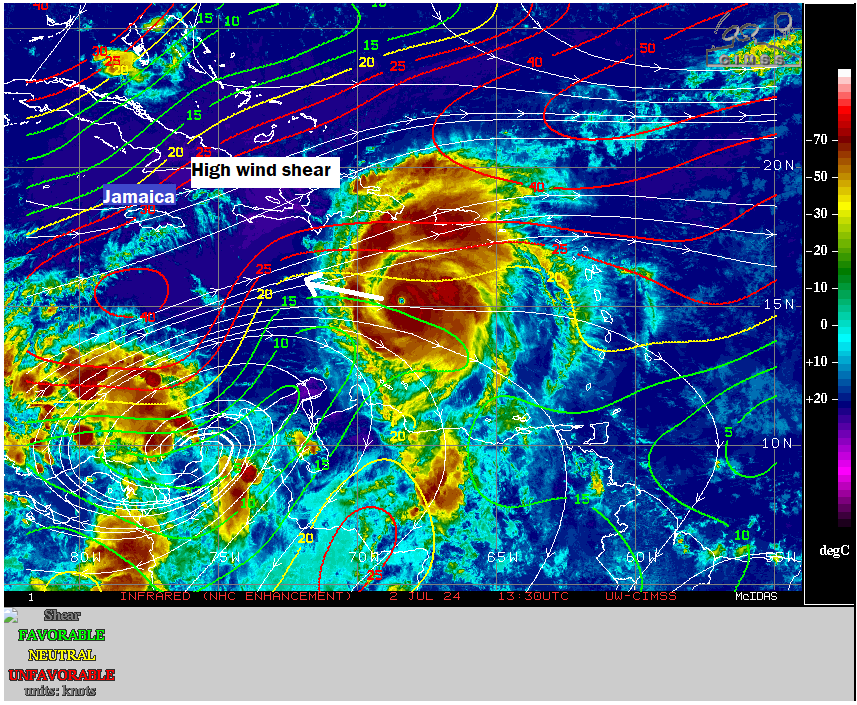

On satellite, Beryl looked great this morning, and while it still looks great, there are at least some signs that shear is beginning to impact Beryl a bit on the west side.

You can see a more ragged appearance to the eye and eyewall, and even what looks to be a little dry air just outside the core in the western semicircle of Beryl. Whatever the case, the thought is that Beryl’s intensity has peaked, and it should now begin to undergo a steady decline. Beryl is about to plow into 20 or more knots of wind shear.

Wind shear is complicated with storms of this intensity. Theoretically, it should just start to feel the shear and begin a steady, if not rapid weakening. Modeling says this will be the case. The majority of modeling weakens Beryl to a category 2 or weaker storm by Thursday morning. But in storms of this intensity, shear can be a little funky and find ways to help the storm “ventilate” somewhat. In my opinion, this is not going to be the case with Beryl; it should weaken as forecast, perhaps at a slower rate than what models suggest. However, there is inherent uncertainty here, and that’s why we would tell folks in Jamaica to prepare for a serious, major hurricane.

In addition to the wind and surge impacts of a major hurricane, flooding from rainfall is a possibility, if not likelihood as Beryl passes southern Hispaniola and Jamaica.

According to Sam Lillo of DTN weather, who has been posting frequent statistical nuggets on Twitter/X regarding Beryl’s unprecedented nature about Beryl’s forward speed. Over a 6 hour period, Beryl is the fastest known moving category 5 storm on record. As noted by him and some others, Hurricane Allen in 1980 and Janet in 1955 also had some extreme forward speeds for category 5 storms. Either way, Beryl will end up atop or near the top of many charts once all is said and done for earliest and easternmost and fastest for storms of this intensity.

What comes after Jamaica for Beryl?

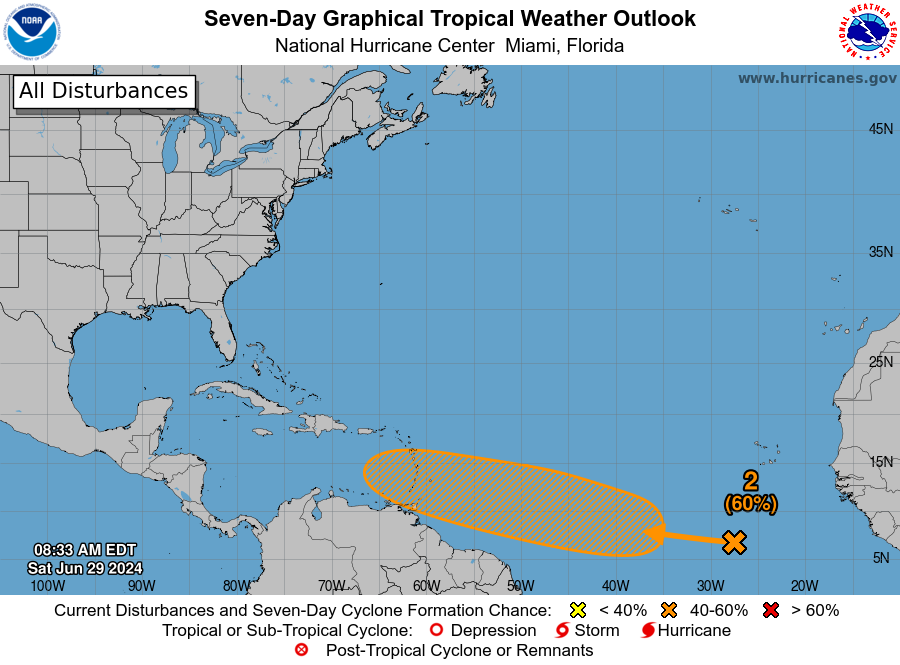

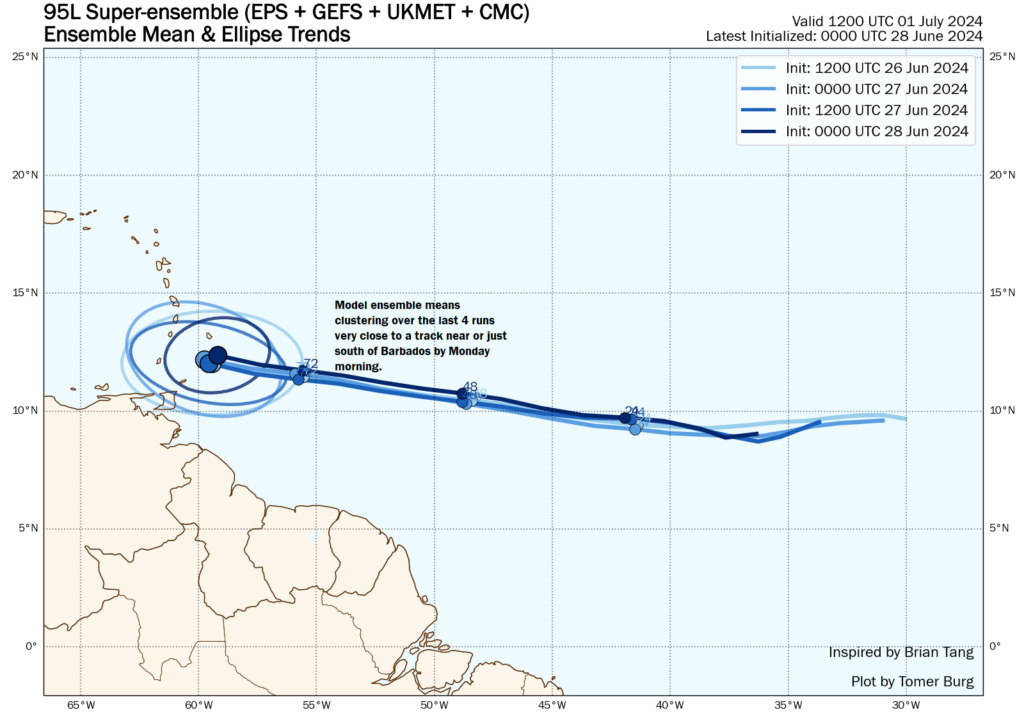

The main near term concern is for the folks in Jamaica and the Caymans. Beyond that, the forecast is contingent on a number of factors. Over the last 48 hours, we’ve seen a slight northward shift in Beryl’s forecast track as it comes west.

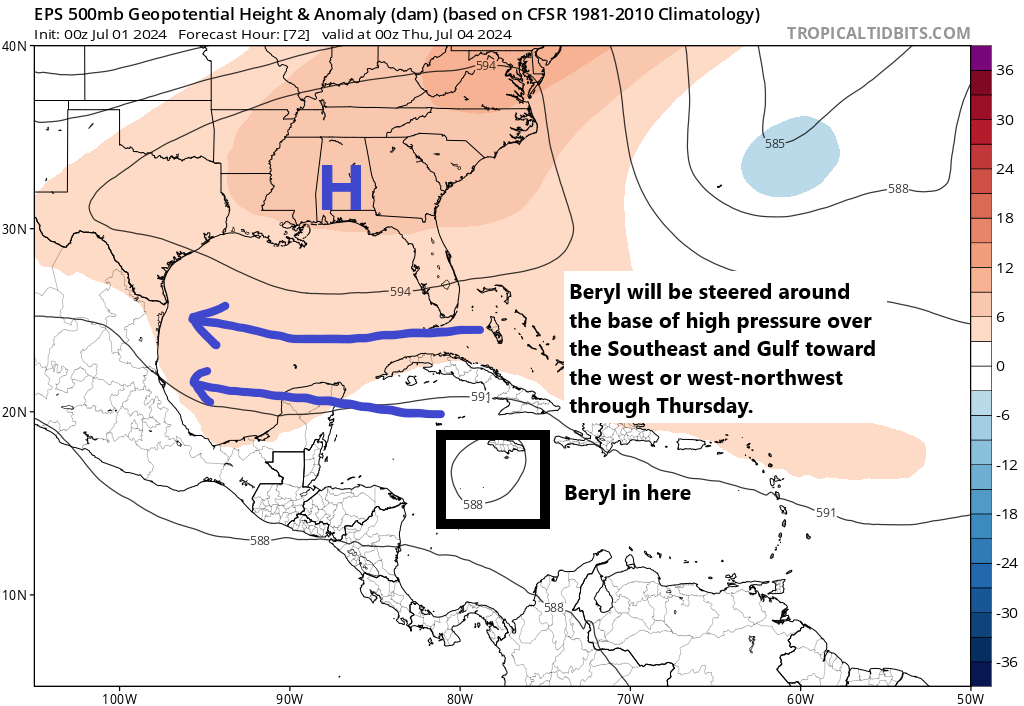

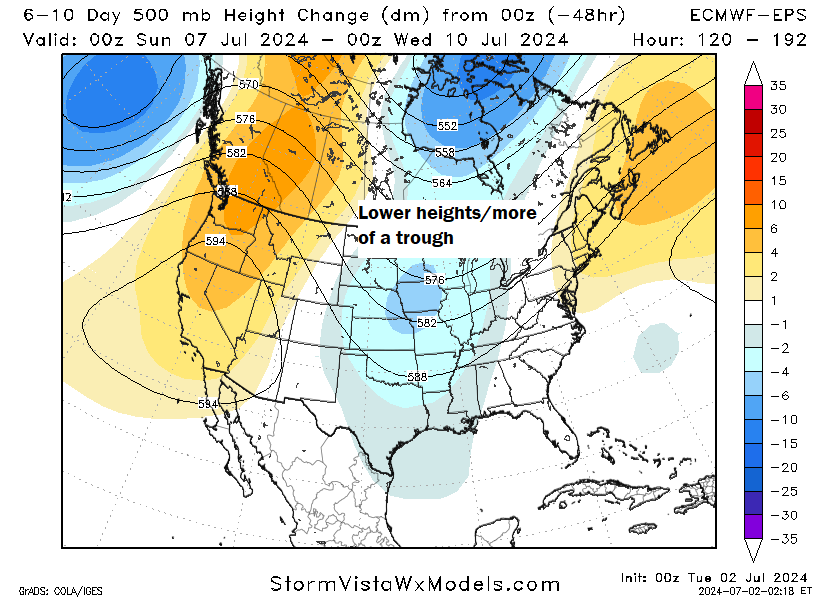

This has implications for the Yucatan and perhaps the Gulf as well. Why is Beryl trending more north? For one, exploding into a category 5 storm allows it to gain some added latitude. But secondly, the U.S. pattern has changed somewhat. If you look at how the European ensemble’s 6 to 10 day forecast has changed in the last 48 hours, the tendency has been for the trough over the Central U.S. to strengthen, thus weakening the ridge of high pressure in the South.

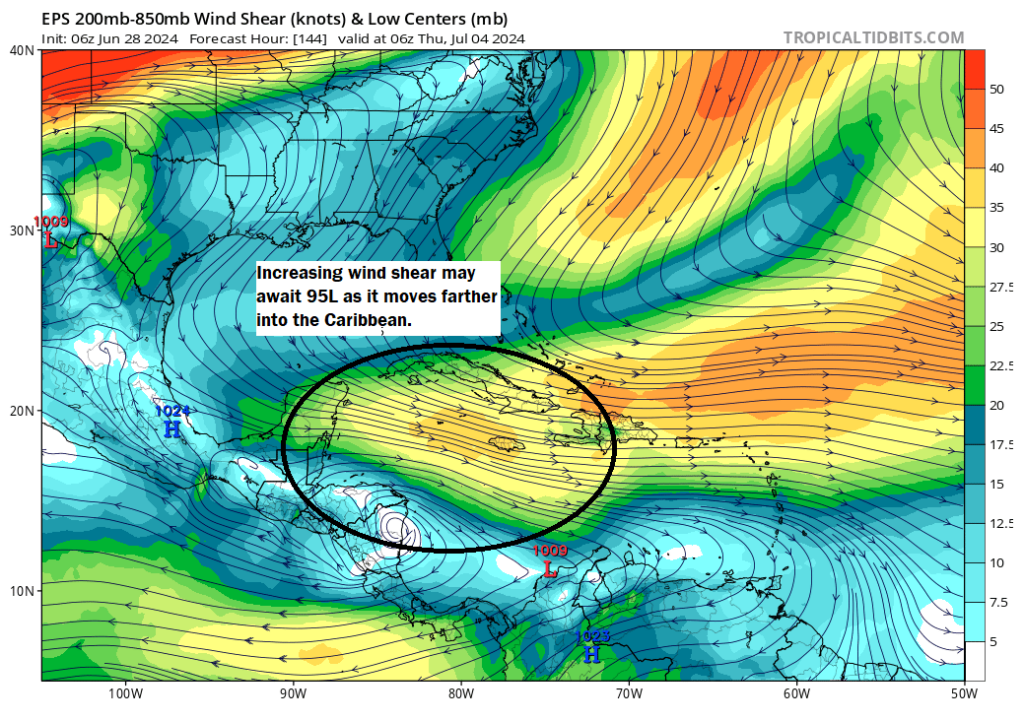

But there’s a lot of nuance to this. For one, if Beryl does weaken as expected, this would have only a modest impact on the final track, keeping it south across the Yucatan and into Mexico. If Beryl does stay stronger than forecast or somehow intensifies as it comes west into the Gulf, it would be more apt to “feel” the stronger trough and come north. You can see this on the Euro ensemble where stronger outcomes are mostly skewed north and weaker outcomes are mostly skewed south.

There’s a reason we have been apt to not speculate on what would happen to Beryl as it came west, rather trying to focus on what would impact Beryl. These changes offer a wrinkle. Should you worry on the Texas or Louisiana coasts? No, but you’ll want to keep an eye on this. For one, there seems to be a fair bit of support for somewhat hostile upper air conditions in the Gulf when Beryl arrives, so there’s no guarantee this will just explode when it gets there.

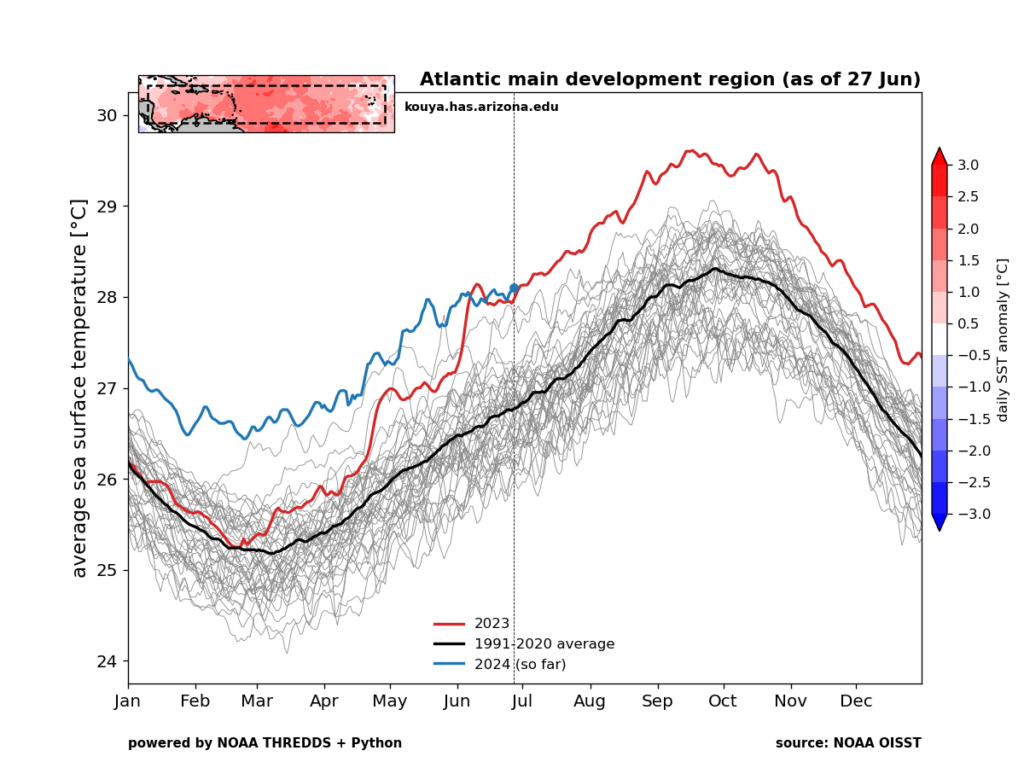

That said, we’re operating in a very odd world right now. Gulf of Mexico water temps have drifted under record levels thankfully, but it’s still warmer than normal overall. So I don’t want to overpromise anything at this point. The best we can tell people to do is continue watching. If Beryl makes it to the northern Mexico, Texas, or Louisiana coasts, the impacts would probably begin late Saturday night or Sunday.

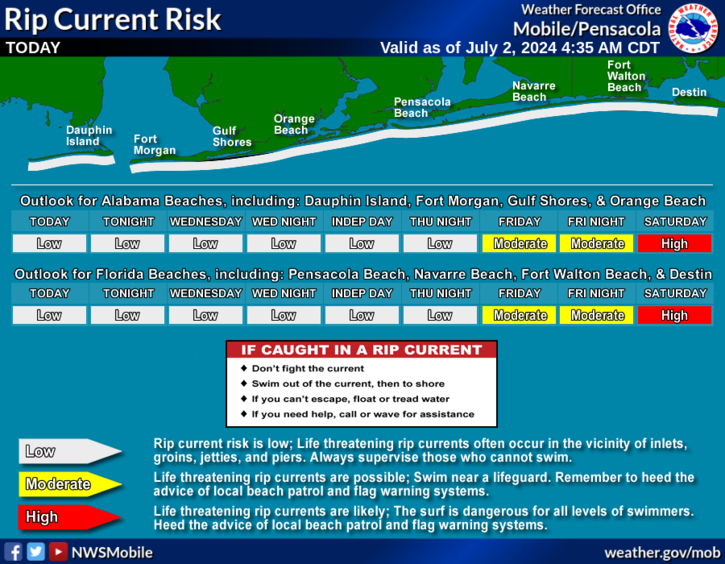

One other quick word: A lot of people will be traveling this weekend to beaches and such. Rip current risk in the Gulf is going to increase later in the weekend as some of the swells from Beryl reach the coast.

Please use caution if you’ll be on the beach this weekend. Even the best and most experienced swimmers can struggle with rip currents, so it’s advised to swim near a lifeguard and follow any warnings or caution notices.