Headlines

- Invest 94L in the Caribbean is unlikely to develop, but if it tracks a bit to the north, it has a puncher’s chance in the Bay of Campeche.

- A robust signal in modeling exists for the tropical wave around 30°W in the Atlantic to organize as it tracks toward the islands next week.

- The wave behind that is worth watching as well.

Invest 94L’s Caribbean cruise looks mostly uneventful

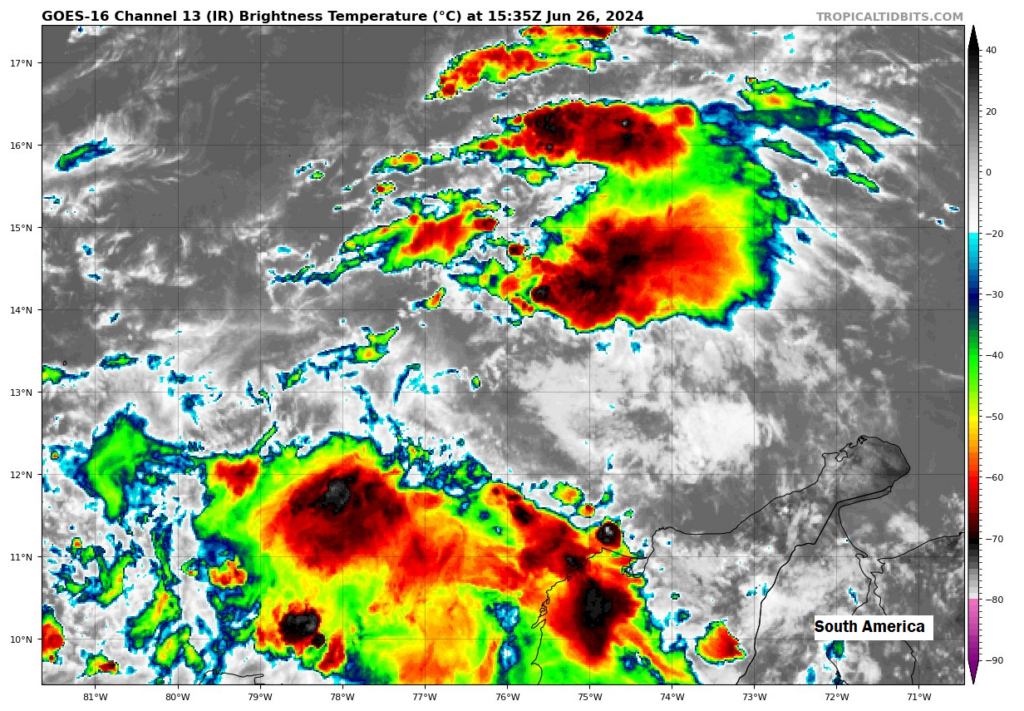

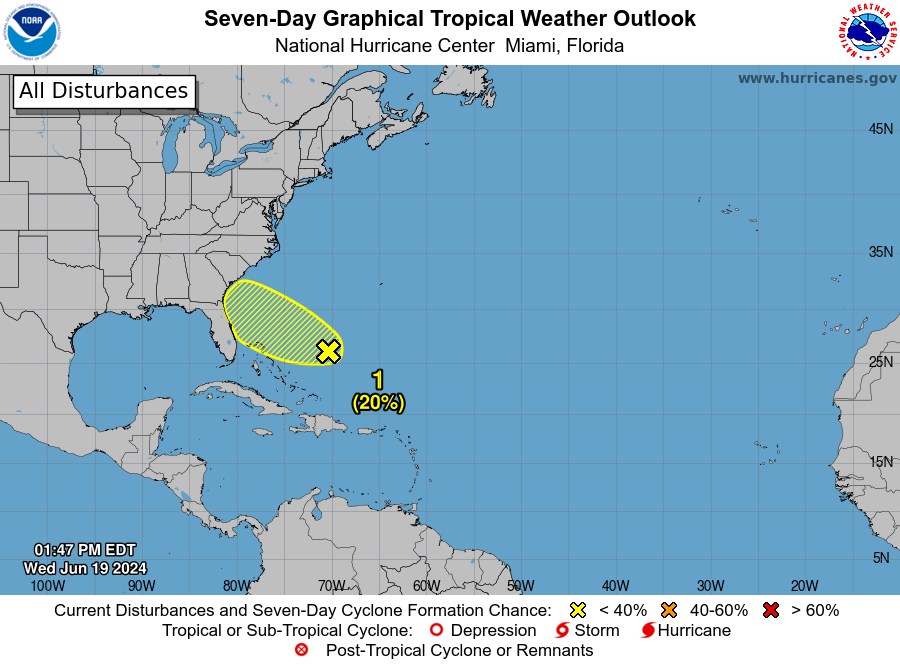

Yesterday, I noted that June would end on a quiet note. Well, “quiet” is a relative term. We have two systems to watch right now, and Invest 94L is the closest to land at the moment. If you look at it on satellite around midday Wednesday, you probably are not terribly impressed.

The system is sort of split right now between high shear to its north and more hospitable shear to its south. This basically means that it has a chance to organize over the next few days, but it would be fairly unlikely and certainly with limited upside to intensity. This situation isn’t going to change much before it runs into Central America or the Yucatan this weekend.

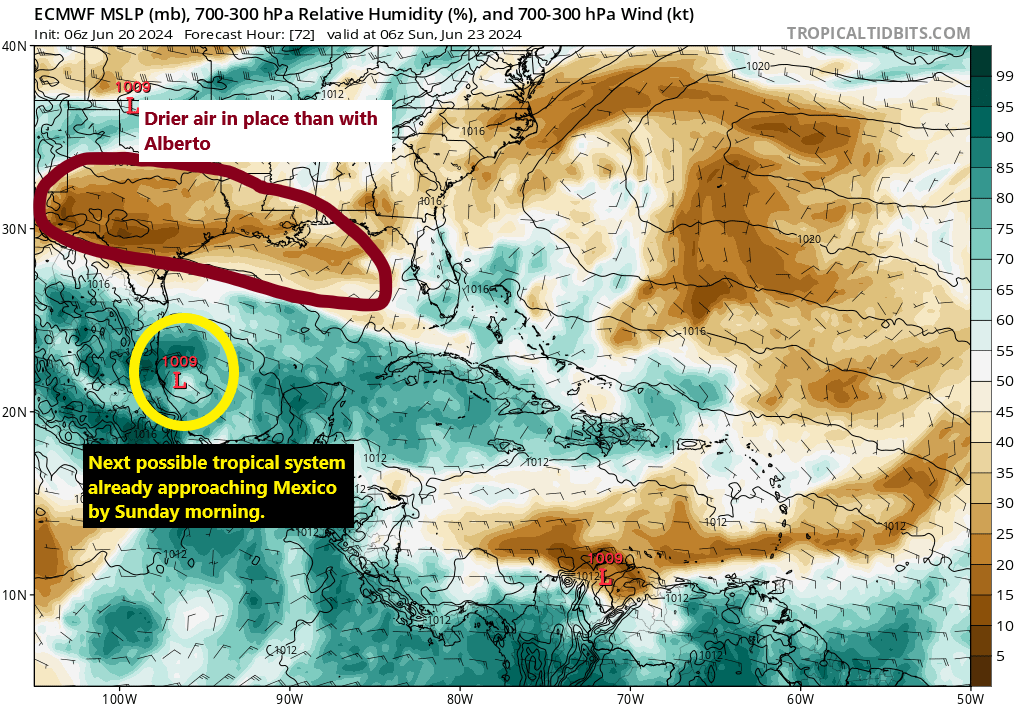

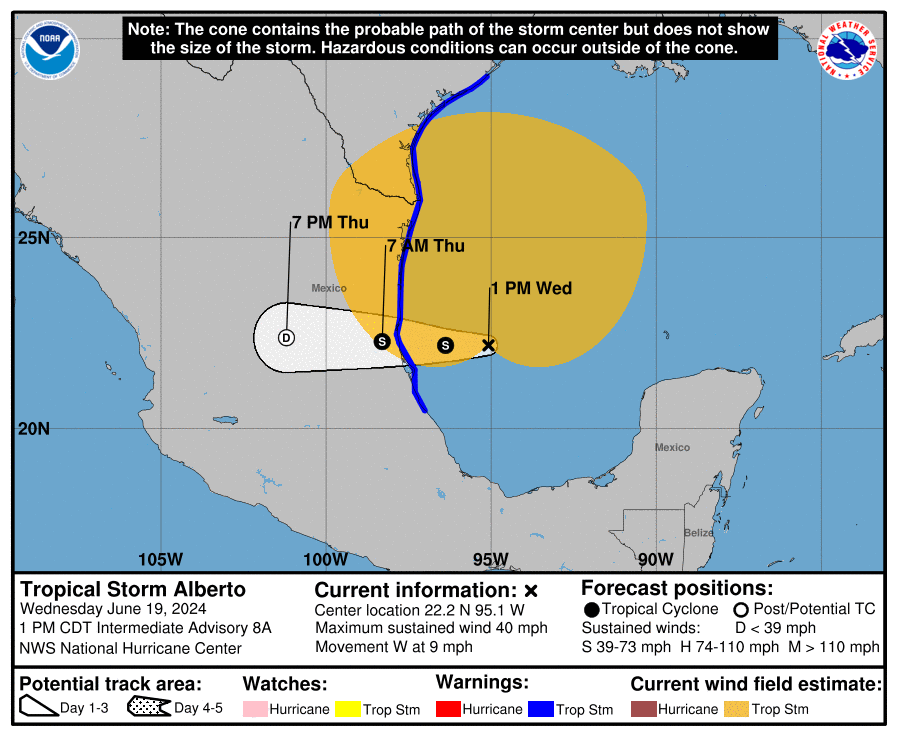

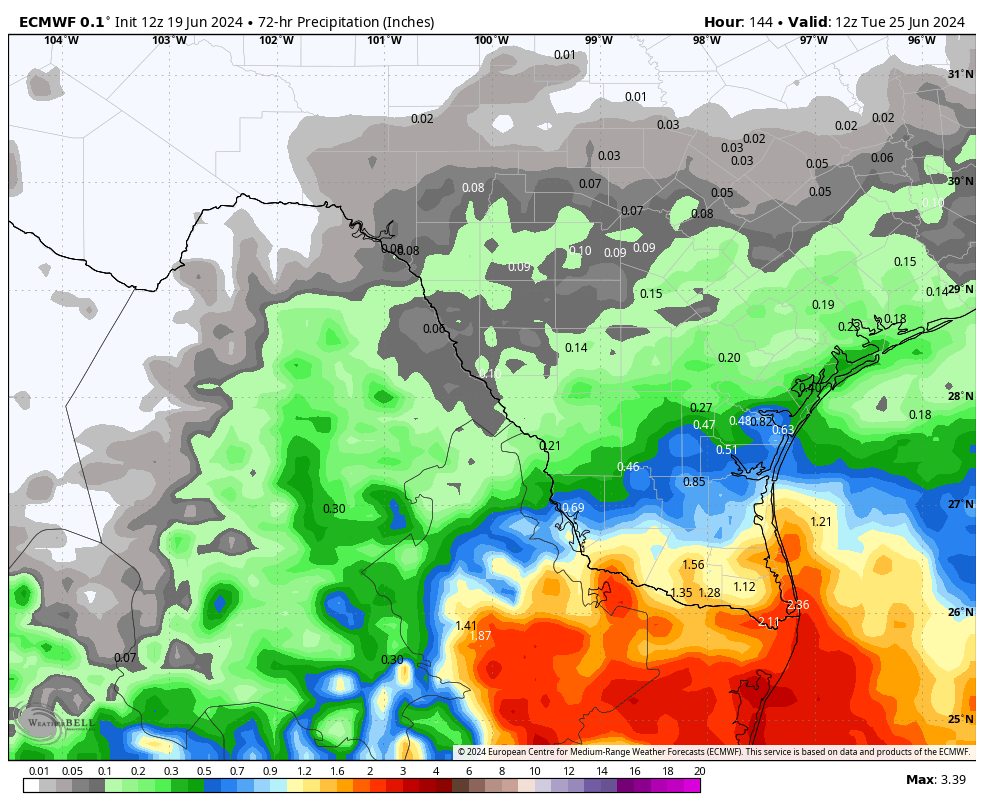

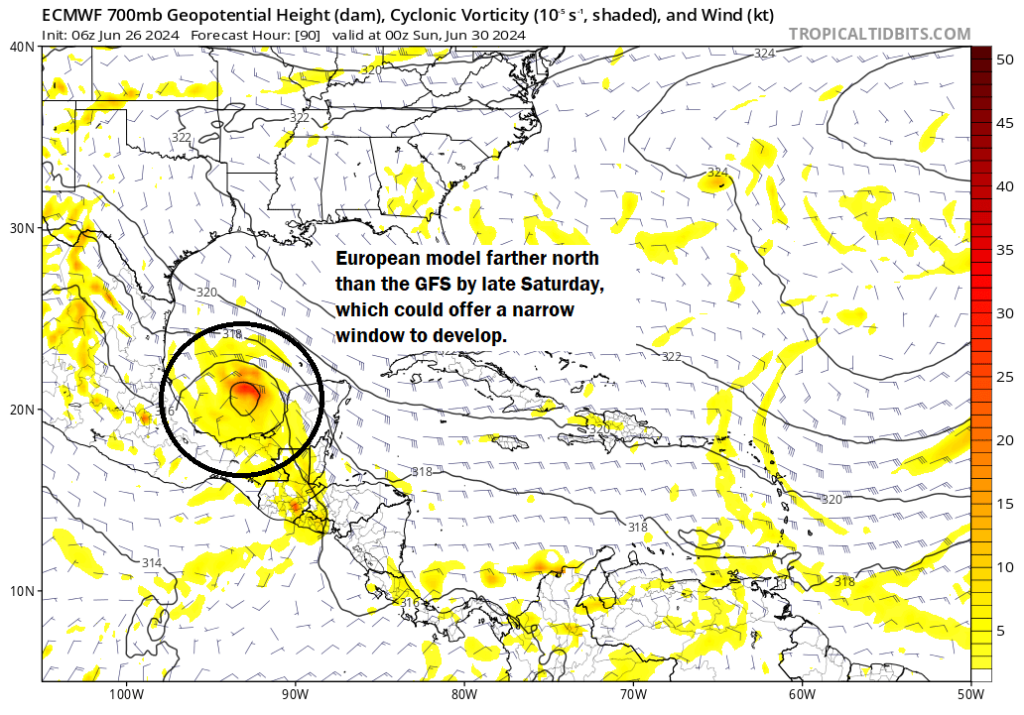

I think Invest 94L’s best chance to organize may come if it crosses into the Bay of Campeche, something the Euro suggests will occur. The GFS model keeps the system really disorganized and basically over Central America and southern Mexico through the weekend. If the Euro is correct, 94L will emerge in the Bay of Campeche later on Saturday and progress into Mexico, a la the last couple of systems in this area.

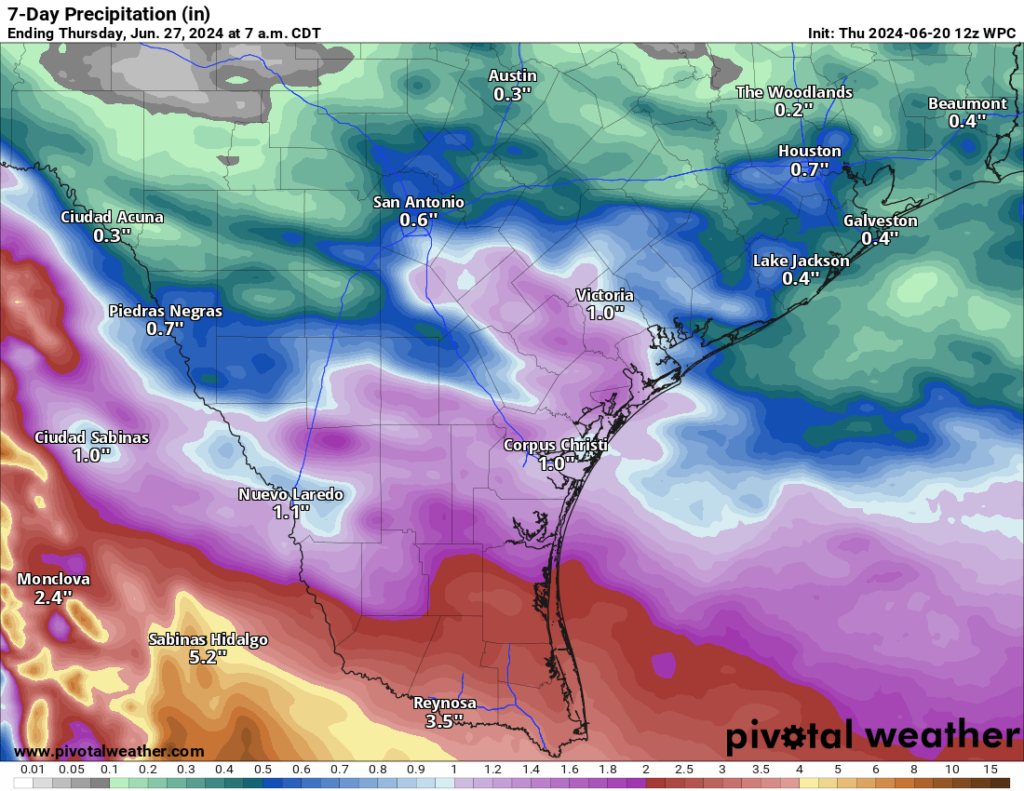

It would have a narrow window to organize before coming ashore if the Euro is correct as shown above. I would probably split the difference between the two at this point, keeping a very slim chance it can get organized before heading inland. Either way, additional rain is possible in the Yucatan and Mexico from Invest 94L as it comes west.

The Atlantic is priming itself to run ahead of schedule

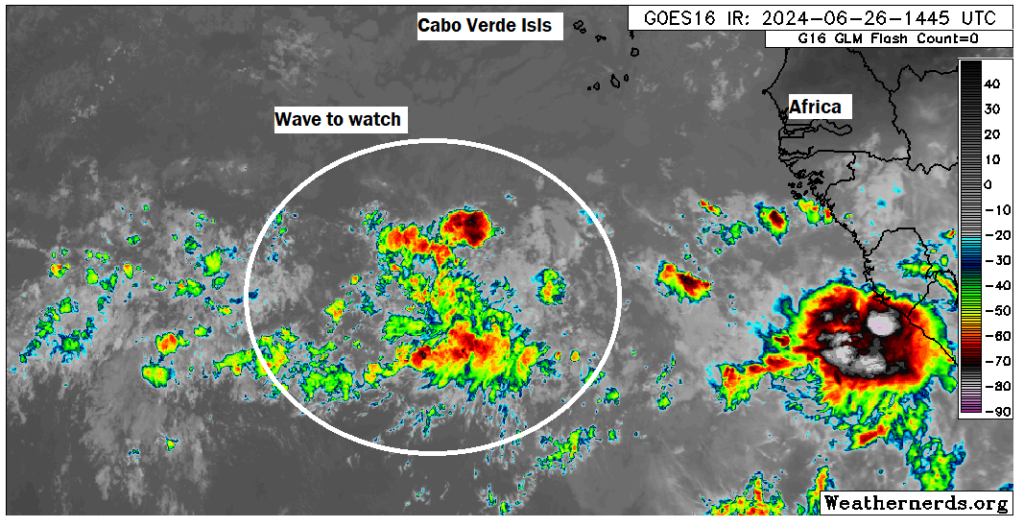

More attention will probably be focused on the deep Atlantic heading into next week however. A tropical wave was located around 30°W longitude today, tracking west.

The National Hurricane Center assigned 30 percent odds of development to this wave over the next week, which seems like a good opening volley. Modeling has been fairly aggressive with this, as both a number of GFS and European model ensemble members try to spin this one up into a depression or storm by the time it gets to the Caribbean islands. It would be rare but not totally unheard of to see a system form out here this early in the season. Per Kieran Bhatia, a leading hurricane expert in the insurance industry, only two systems have formed east of 51°W longitude in June since 1960, most recently Elsa in 2021. Whether this forms in June or the first days of July, if at all is still up for debate, of course. But it is worth watching.

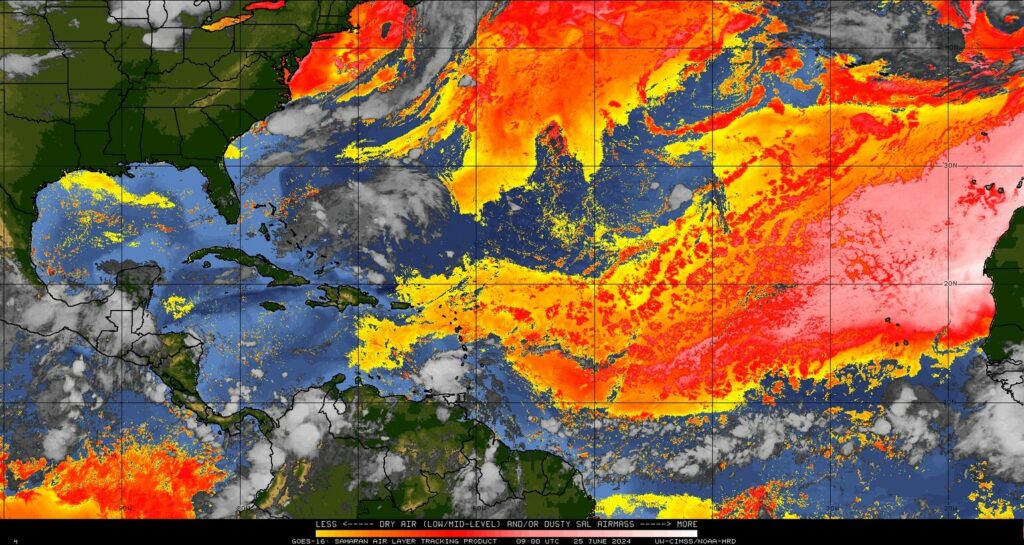

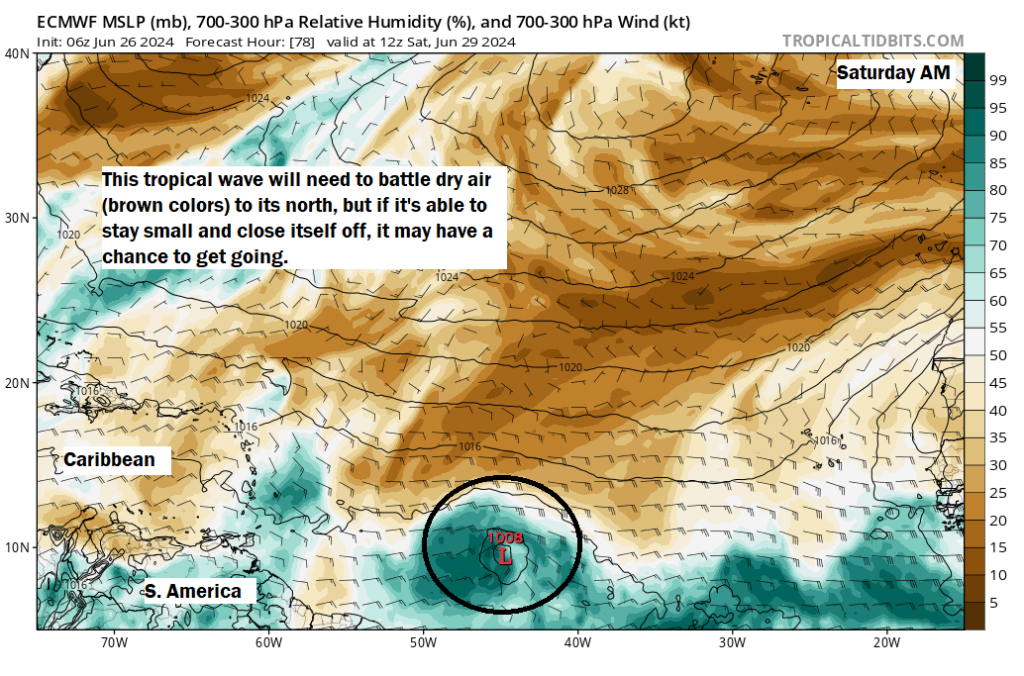

Currently, this wave is located in an area with a lot of dry air to the north as Saharan dust expands across the Atlantic. In about 3 days, that situation does not really change. The Euro and GFS are generally similar about 3 days from now, showing this wave trying to organize east of the islands and very, very far south in the basin.

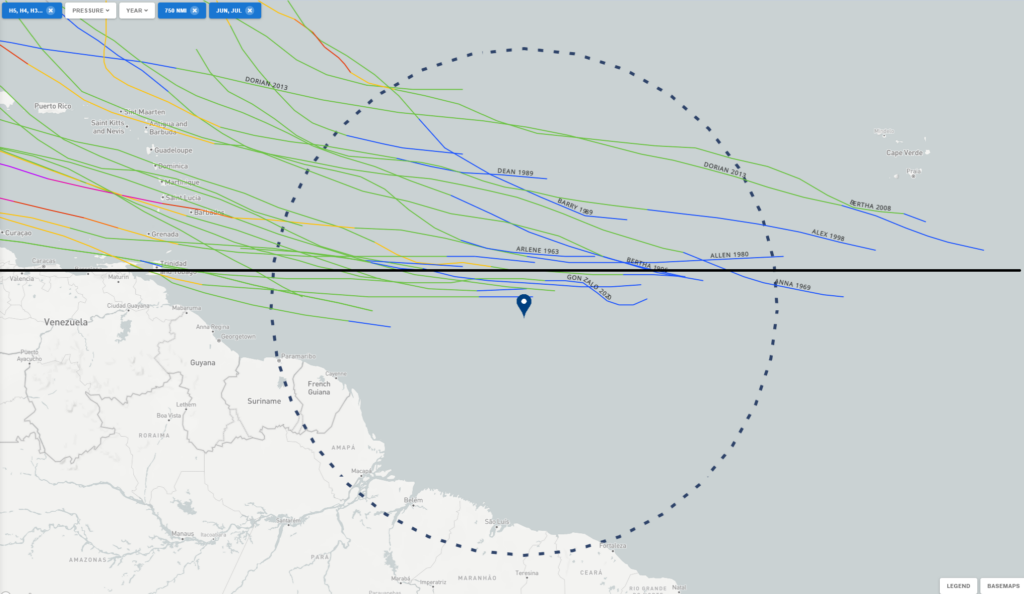

The wave is cruising along around or just south of 10 degrees latitude, a region in which only a handful of June and July storms have generally developed.

These storms ended up with mixed outcomes, including a couple hurricanes, a couple dissipating in the Caribbean, and a couple making it toward the Gulf. No strong signal exists either way. Whatever the case, the story with this wave’s southern track is that it may benefit its long-term ability to organize. If it can consolidate as a smaller system farther south, it would be more likely to incubate itself from the dry air and dust to its north, giving it an opportunity to slowly intensify as it works toward the Caribbean. If it fails to do this, it will likely struggle with dry air or wind shear, also expected to be present.

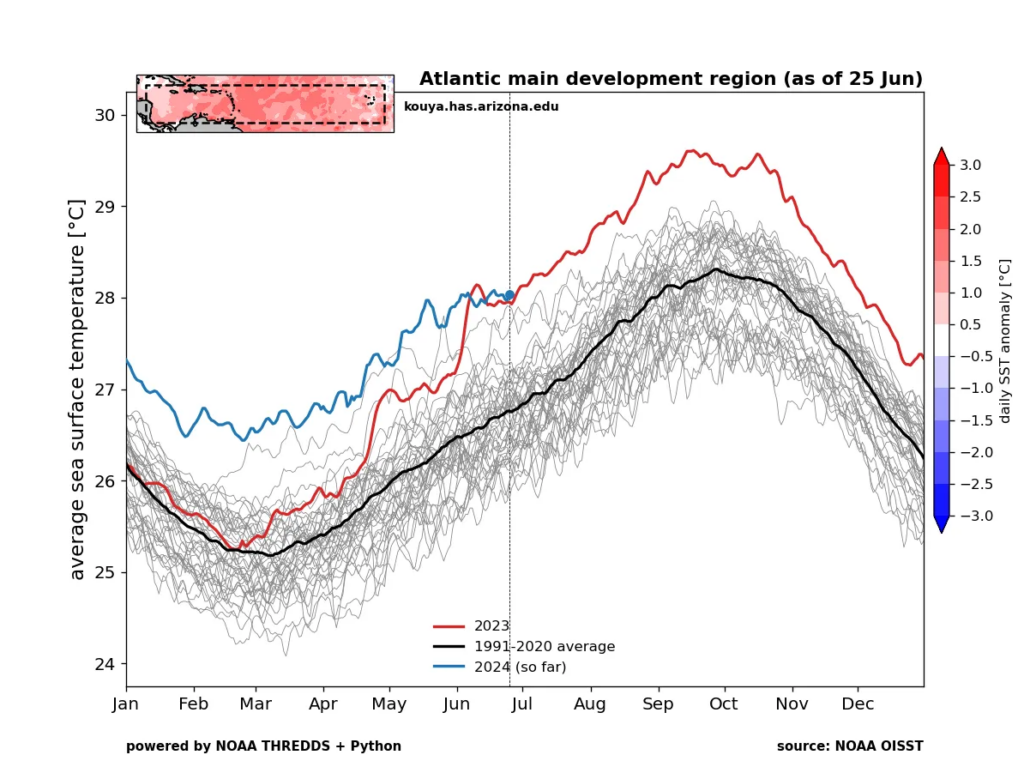

One reason to watch this one is that our sea-surface temperatures in the region are running at or above records set last year and near levels that are normal for late August. So if it finds the right environment, it has a chance to grow. I don’t want to speculate on where it goes just yet, but suffice to say, while wind shear could ultimately threaten its ability to grow significantly, it’s a little concerning to see the potential of this happening early in the season and so far east, with decent upside risk. Folks in the Caribbean should monitor this disturbance’s progress and check back for updates.

Also, the wave behind this one has shown up at times on modeling with a development opportunity. I wouldn’t worry much about it at this point, but its worth watching as well. The Atlantic seems to think its later July.