3 PM CT Monday Update

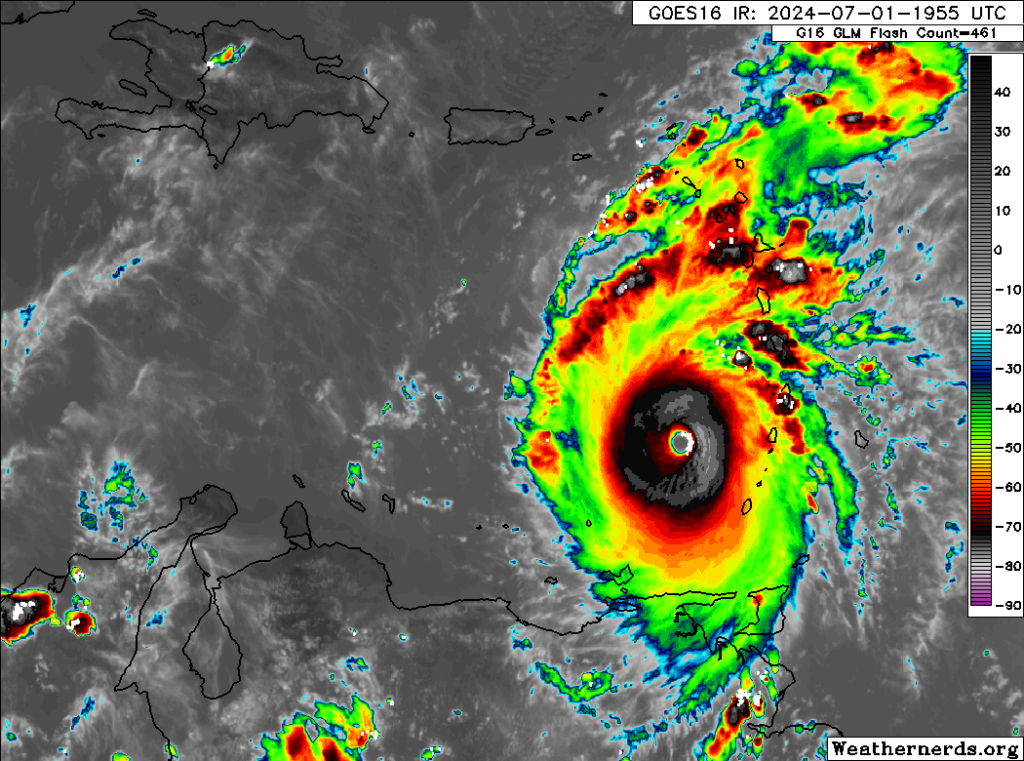

Beryl made a quick landfall this morning on the island of Carriacou just north of Grenada as a category 4 hurricane with 150 mph winds. Beryl remains a beast of a storm, albeit relatively compact in the Caribbean. It will mostly avoid land now for a bit.

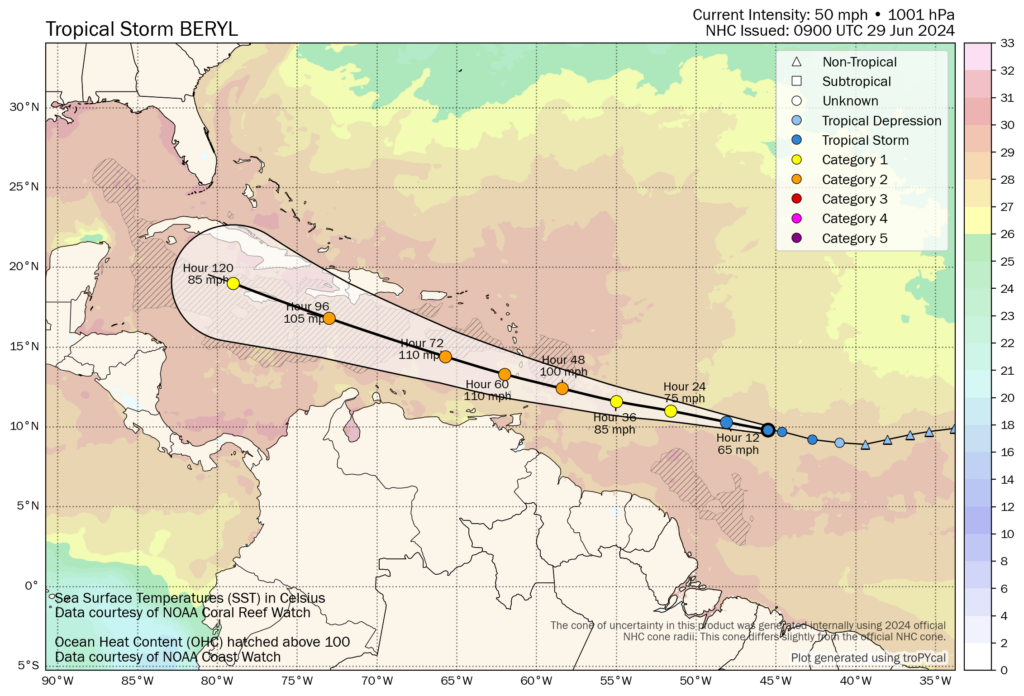

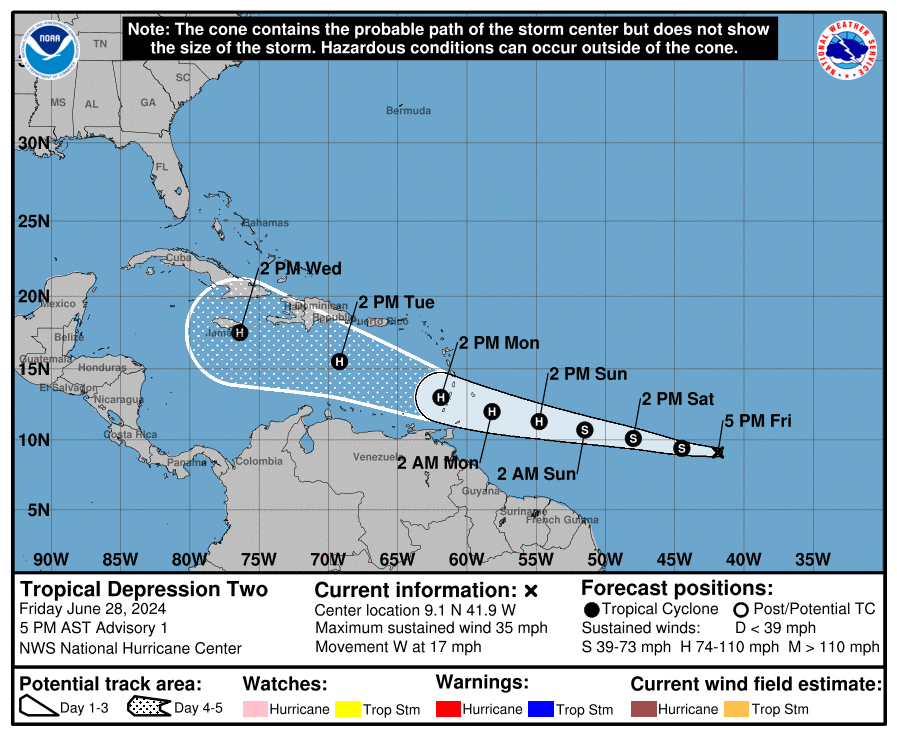

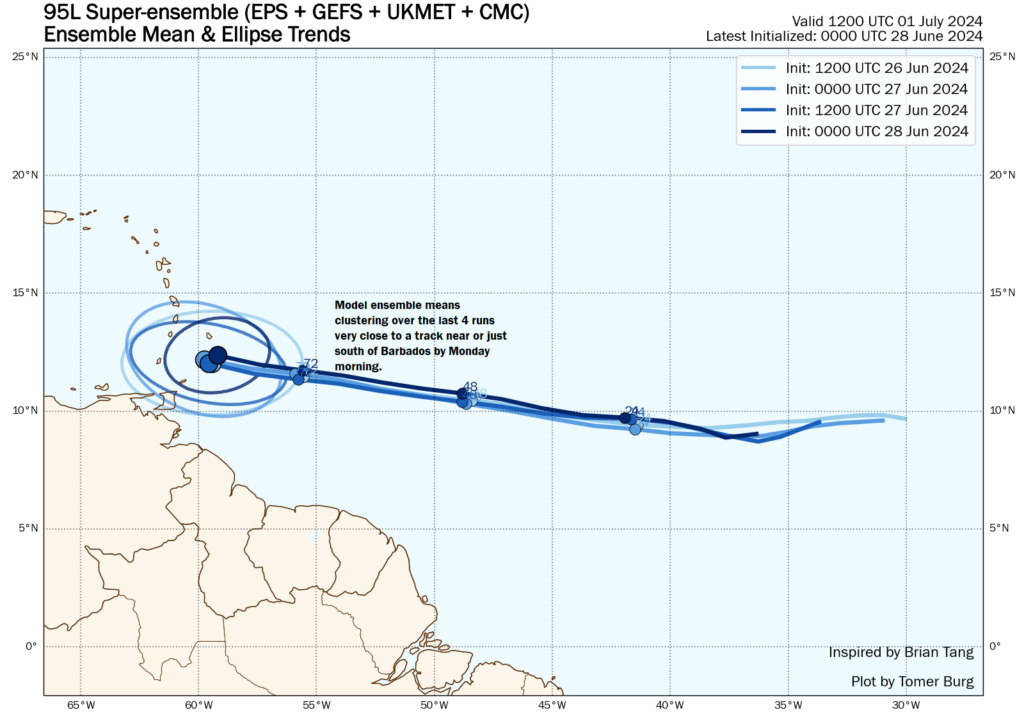

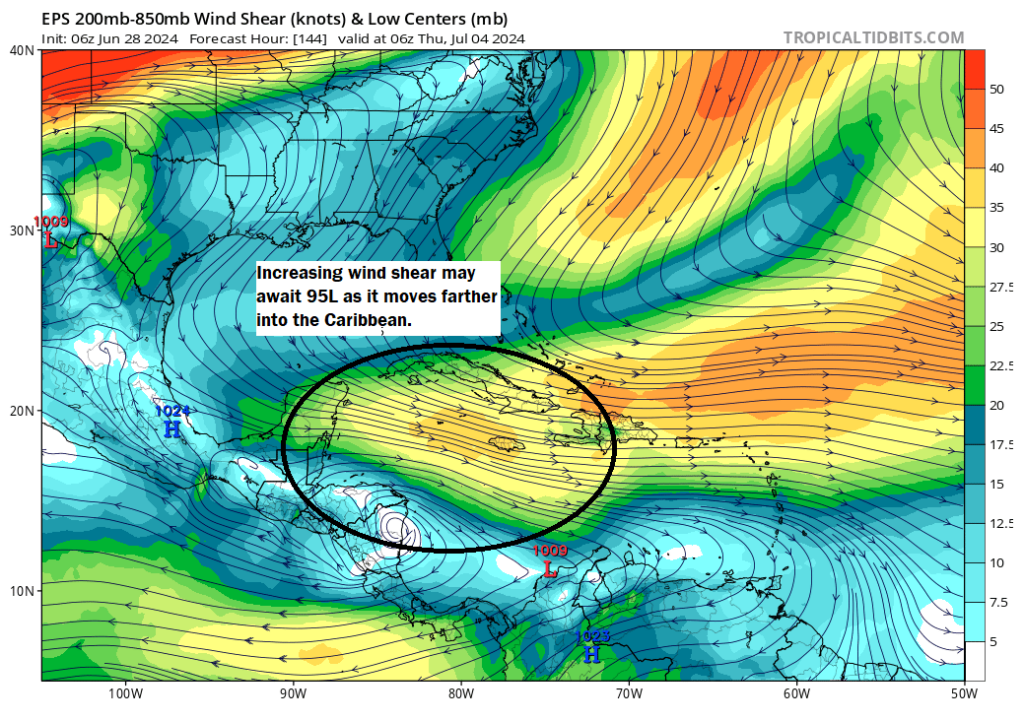

Beryl will track mostly west northwest the next couple days, and it will likely encounter a good deal of wind shear after tomorrow morning, allowing it to begin weakening as it moves toward Jamaica. We continue to believe it will pass south of Jamaica. There remains a good deal of uncertainty beyond the end of the week in terms of where Beryl goes and whether or not it can track northwest enough to get into the Gulf. That remains a low likelihood scenario, and most tropical models agree that Beryl will be disheveled enough to be bullied by high pressure over the Southeast and Gulf to be forced toward Mexico or extremely far south Texas. We’ll continue watching trends, but Beryl’s forecast for the weekend is not much clearer this afternoon than it was this morning.

The morning post follows:

Headlines

- Beryl will make a direct hit across the Windward Islands today, very near Grenada or the Grenadines with impacts beyond there.

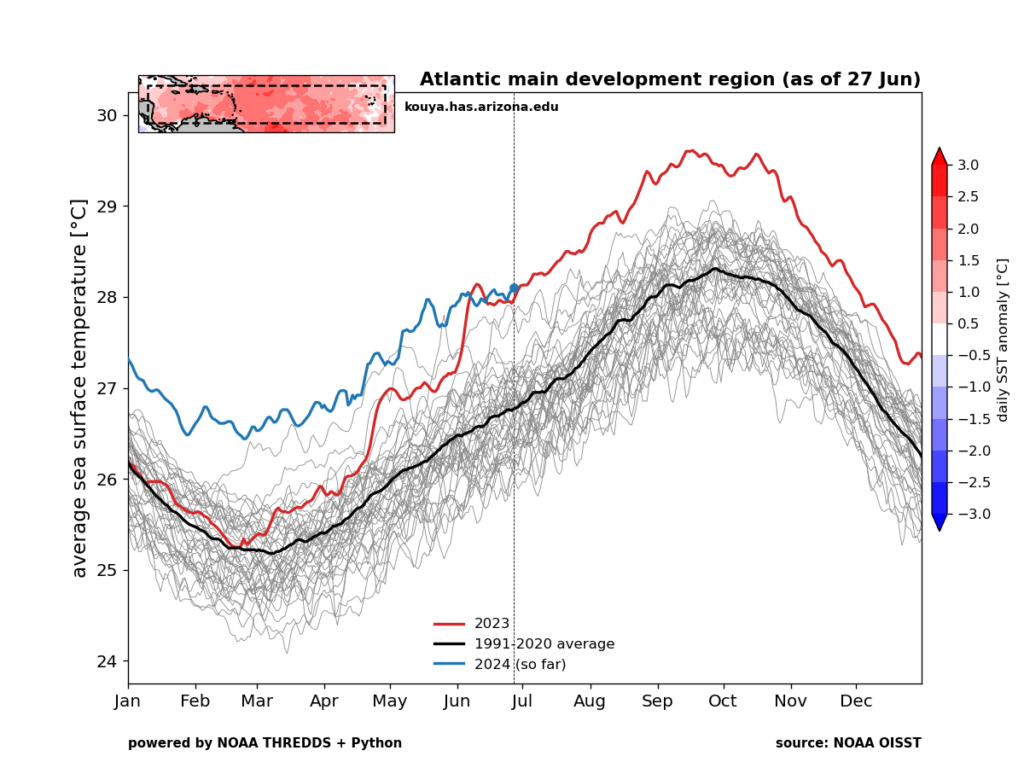

- Beryl is reintensifying after undergoing an eyewall replacement cycle overnight.

- Beryl will track west northwest across the Caribbean, eventually encountering some wind shear that should weaken it a good bit before it passes south of Jamaica.

- Uncertainty remains high on the ultimate track of Beryl beyond the Caribbean, but modeling has made a fairly southward shift since yesterday, keeping most impacts near Mexico. It still bears close watching.

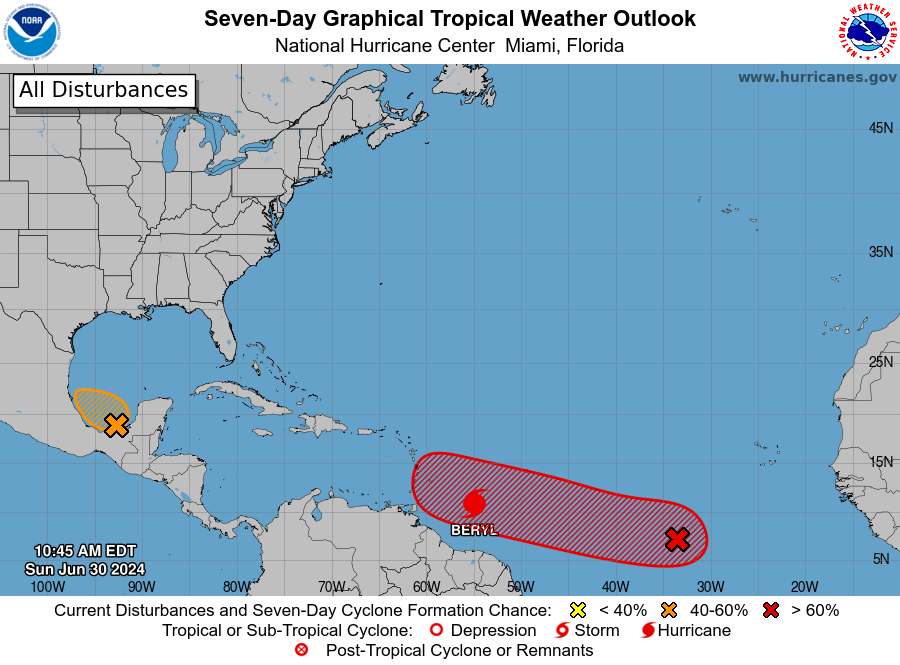

- TD 3 became Chris overnight and is now inland with heavy rain over Mexico, while Invest 96L (unlike Beryl) will take a slow and steady approach to organization over the course of this week.

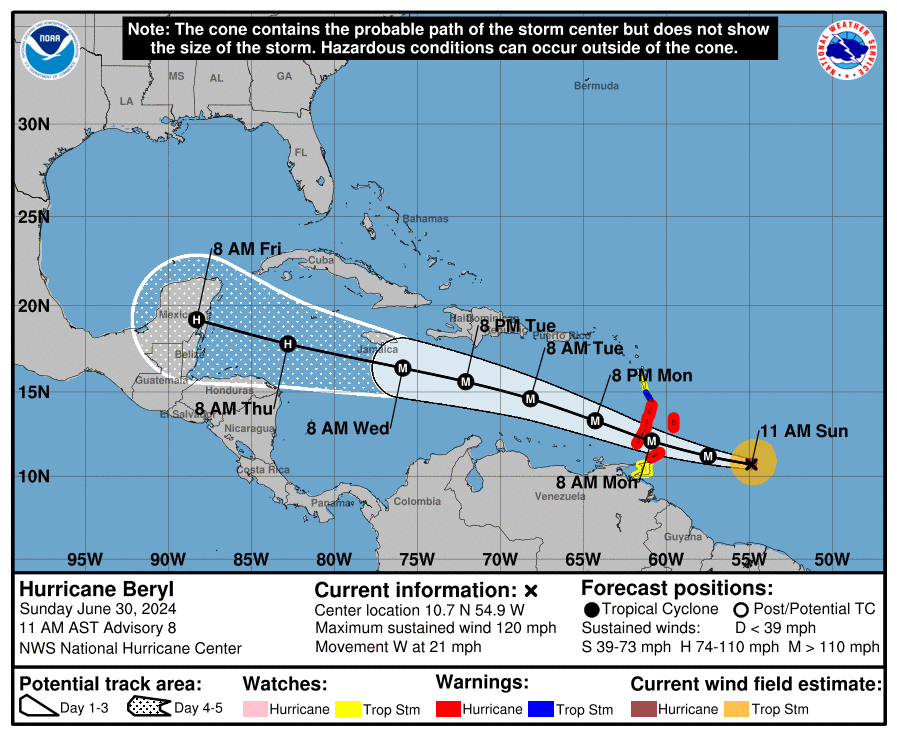

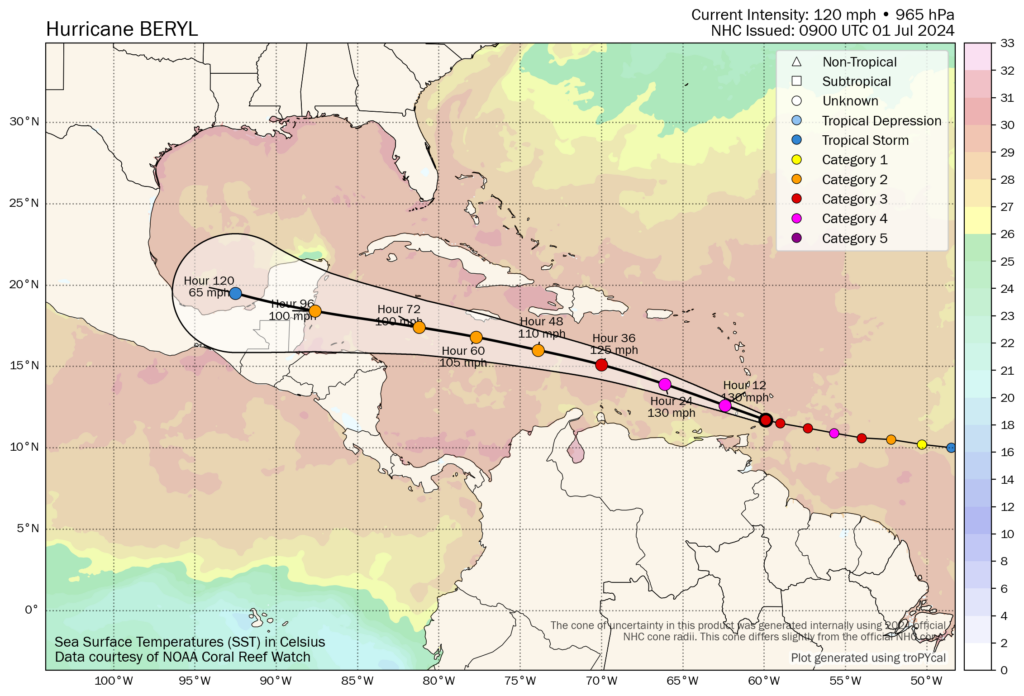

Hurricane Beryl: 130 mph, moving west northwest at 20 mph

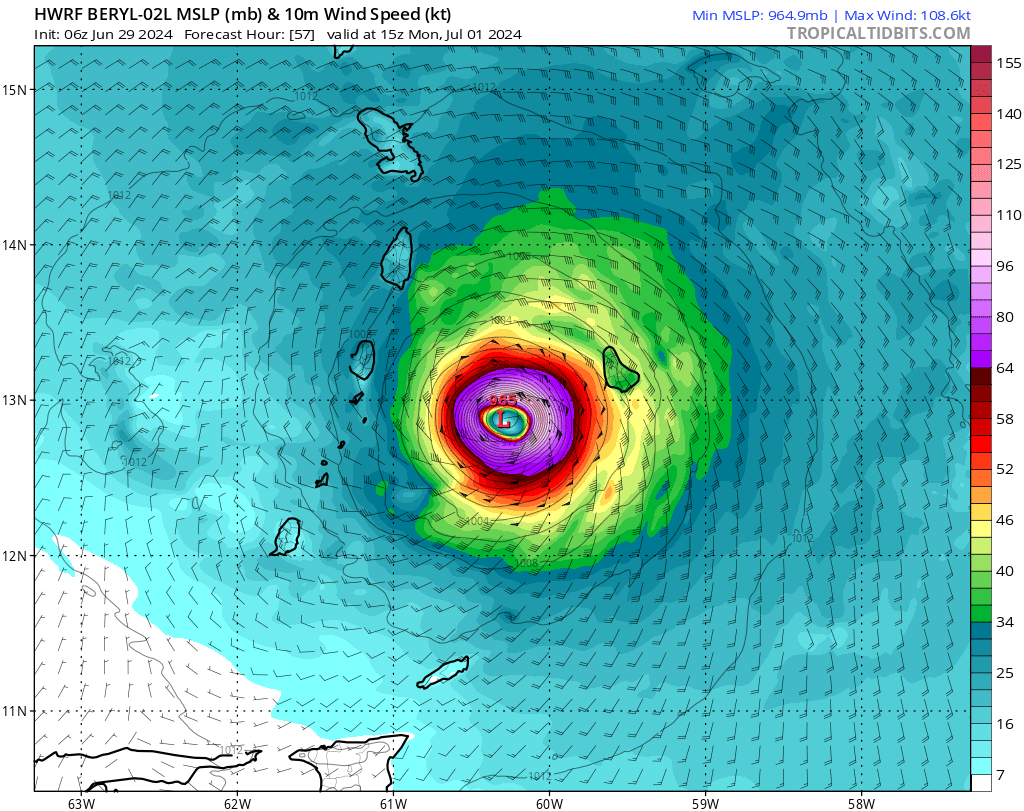

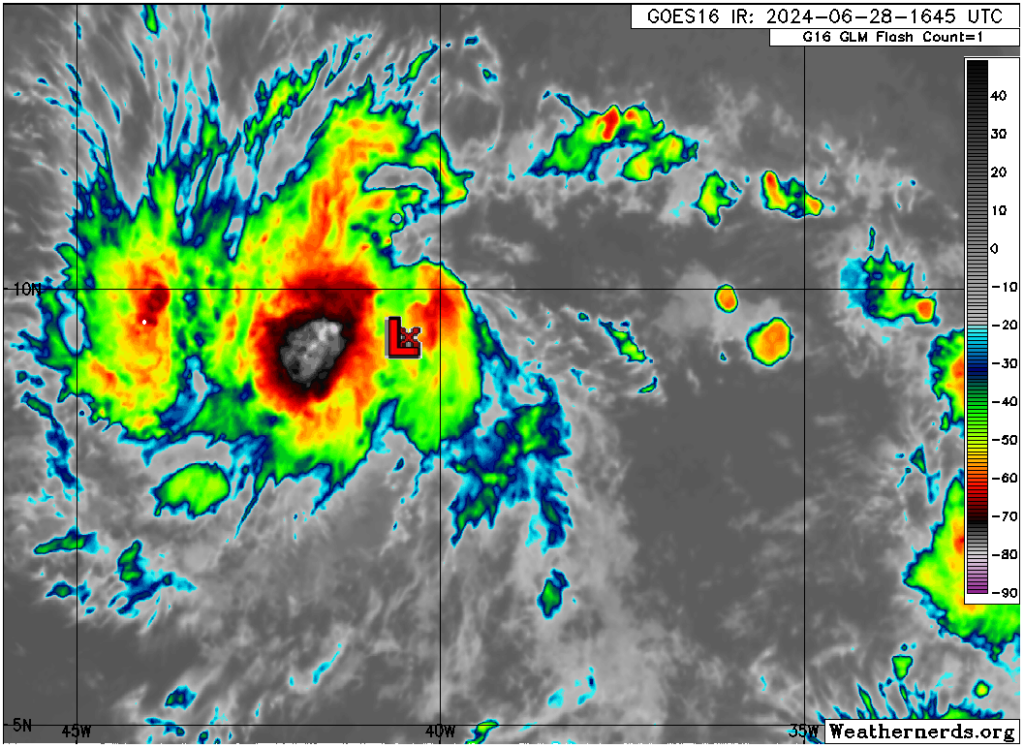

Hurricane Beryl has just undergone what we call an eyewall replacement cycle (ERC). You can read about the nuts and bolts of it here, but in a nutshell, this is where a hurricane basically takes a moment to reorganize itself and expand in size. As a result, Beryl’s wind field has increased with hurricane-force winds now out about 35 miles from the center and tropical storm force winds out 125 miles from the center. Beryl remains relatively compact, but it has grown somewhat.

Unfortunately, since Beryl is wrapping up an ERC, this means it will have an opportunity now to restrengthen. Winds were down to 120 mph as of early this morning from its peak around 130 mph yesterday, but we may see those increase once more. (Editor’s note: They have increased to 130 mph again as of the 8 AM AST advisory)

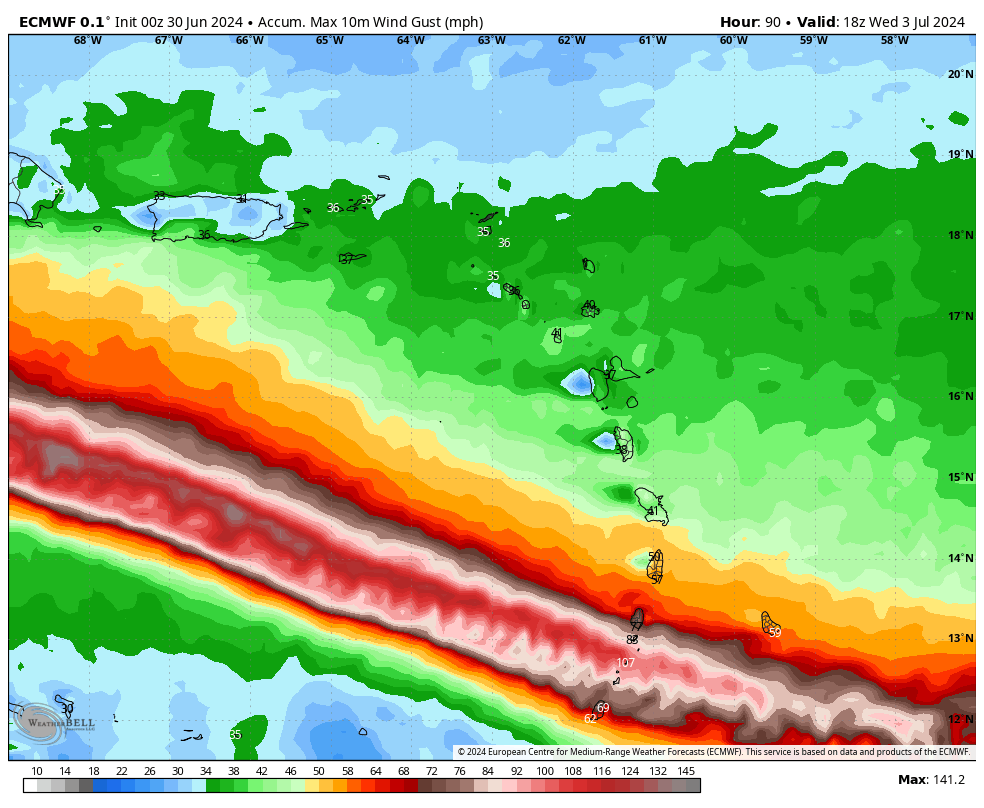

Whatever the specifics are, it’s pretty clear that a major hurricane is going to directly impact the Windward Islands today, with the worst impacts coming near Grenada and the Grenadines, south of St. Vincent.

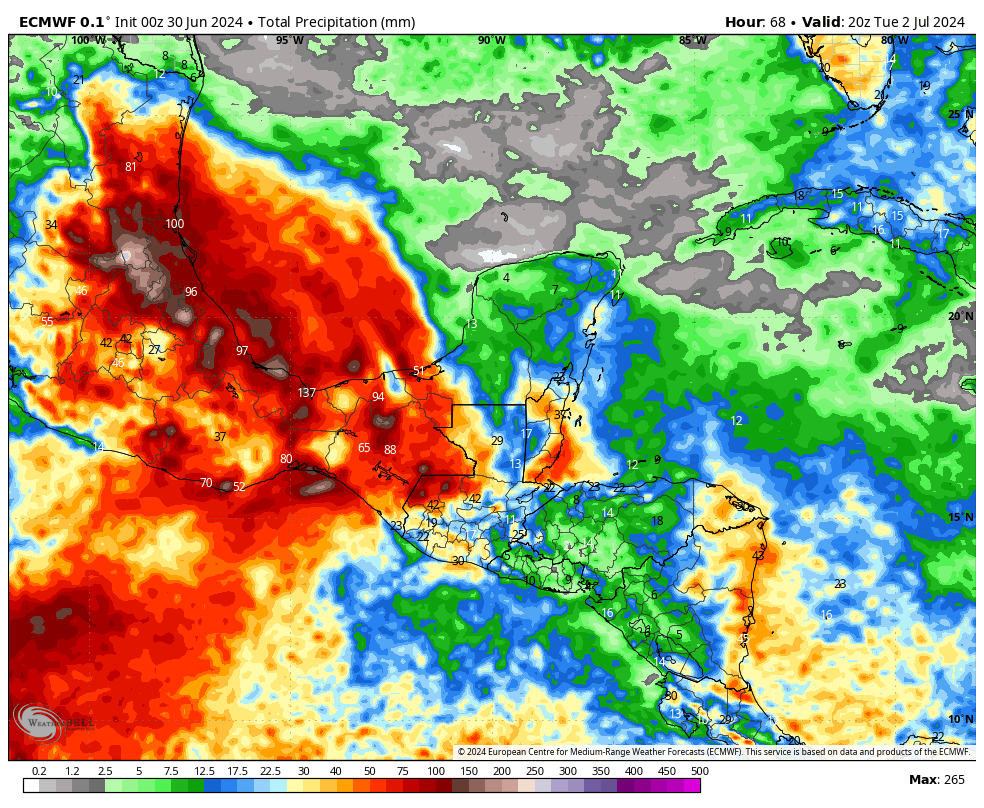

Total rainfall from Beryl will be heavy, but because it is booking it west, the rain totals will generally be 10 inches or less. Surge and wind will be major problems with rainfall a secondary hazard in this case.

Once through the Windward Islands, the next land mass to watch for potential impacts will be Jamaica. While Beryl is likely to pass south of the island Wednesday night or Thursday, avoiding a direct hit, it will be close enough to deliver wind, rain, and surge to Jamaica, and it’s just a question of how much. Notably, Beryl is expected to weaken after tomorrow morning. It will begin to encounter a good bit of wind shear in the central and western Caribbean. The official forecast keeps Beryl a category 2 storm all the way to the Yucatan, but model guidance is actually a little more aggressive in weakening Beryl to perhaps even a tropical storm. While no one should be sleeping on Beryl, this is very likely to be a much different storm in 2 days than it is right now.

For those of you with plans in Jamaica or the Caymans or the Yucatan and Belize, we can’t tell you what to do. Just continue to monitor Beryl’s progress and reach out to your hotel or resort for more guidance.

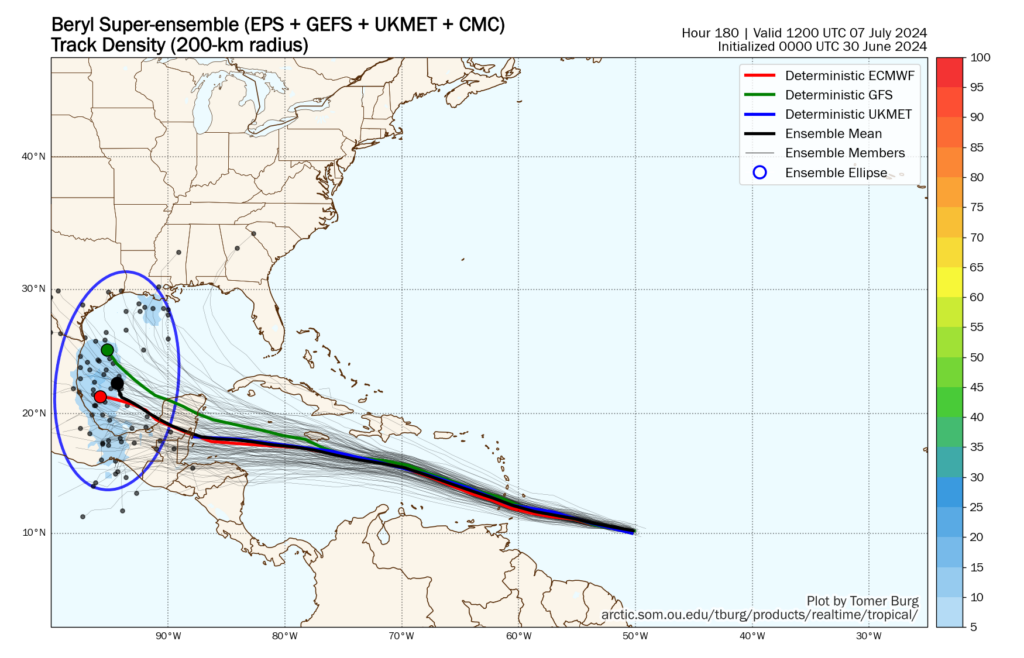

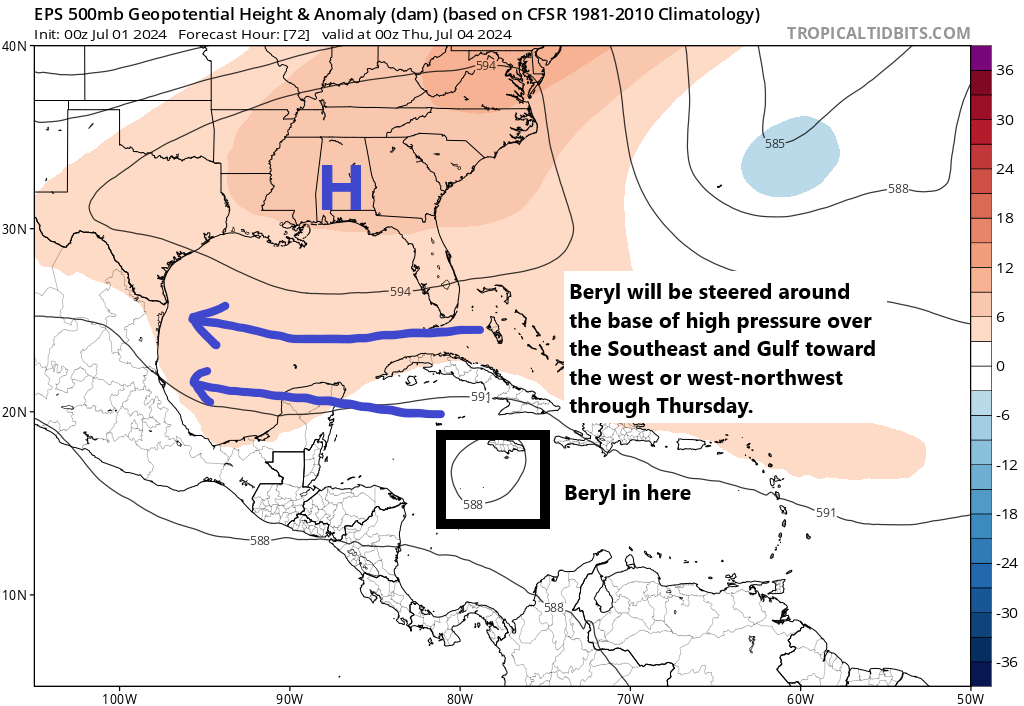

After day 3, the weather pattern will support Beryl continuing west around the base of high pressure centered over the Southeast or northern Gulf of Mexico.

The question will be how long this high stays in tact. The high is expected to weaken by Friday or Saturday. At that point, Beryl should be near or over the Yucatan. The uncertainty then lies in whether Beryl has enough left to it after encountering shear and land to determine if it continues west northwest or shifts more northwest. There is actually decent tropical model agreement that it will continue west northwest, which is close to the official forecast as shown above. A handful of other models suggest it will turn northwesterly toward northern Mexico or Texas.

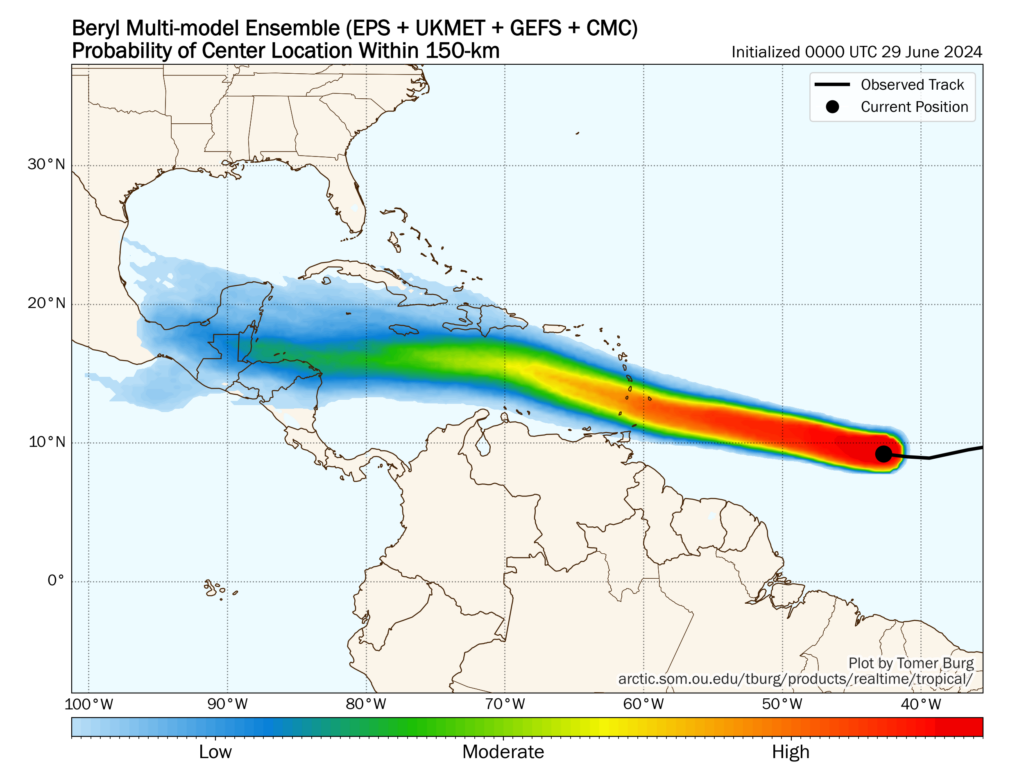

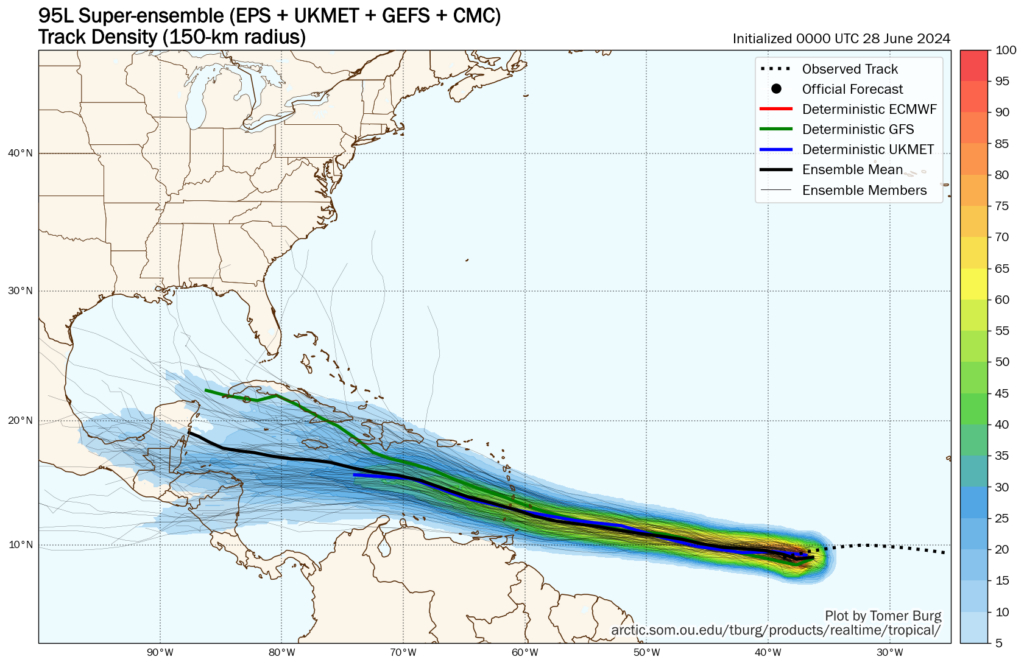

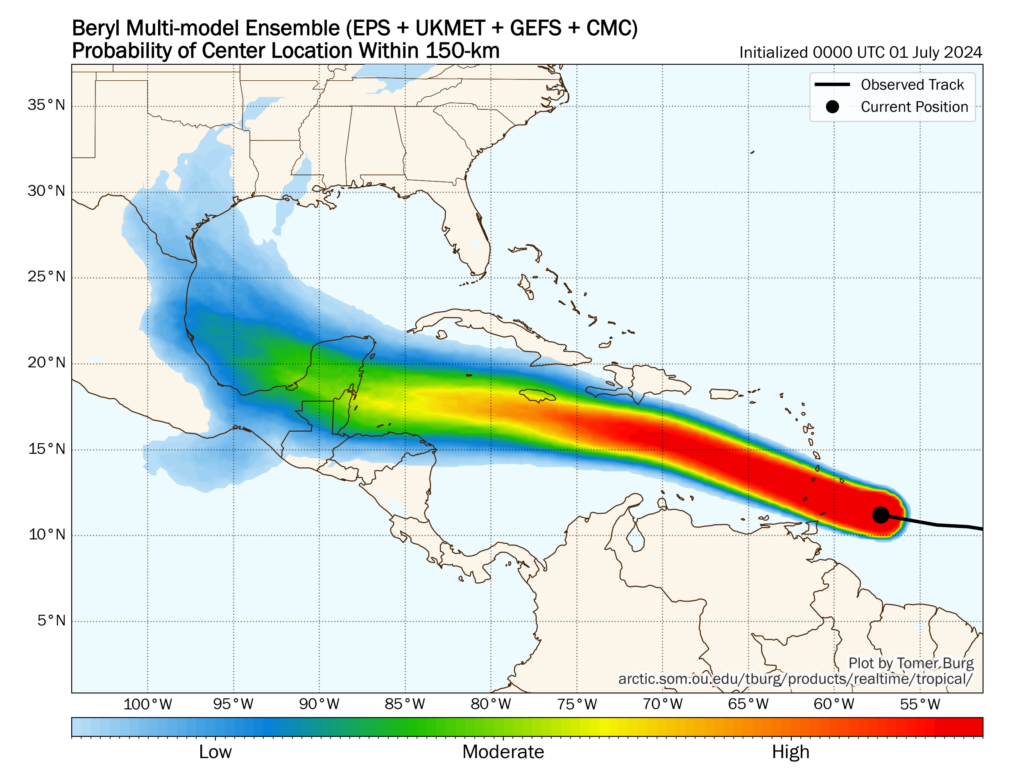

From the track density plot above, you can see that Beryl is expected with high confidence to pass just south of Jamaica and the Caymans before approaching the Yucatan or Belize. Confidence diminishes from there with some models dissipating Beryl and others continuing it across the Bay of Campeche toward Mexico or far south Texas. Again, keep in mind that this will be a much different storm then than it is today, and it will probably need some time to organize itself after reaching land in the Yucatan. Its forward speed is such that it will likely have a limited amount of time to get itself back together as it approaches the coast. Folks in Mexico and Texas should continue to watch Beryl’s progress, but at this point, it’s too soon to get more specific than that.

Stay tuned for more on this, but in the meantime, our thoughts are with the Windward Islands today.

The rest of the crew

Tropical Depression 3 became Tropical Storm Chris overnight and is now inland and once more a depression. It is a heavy rainmaker for Mexico.

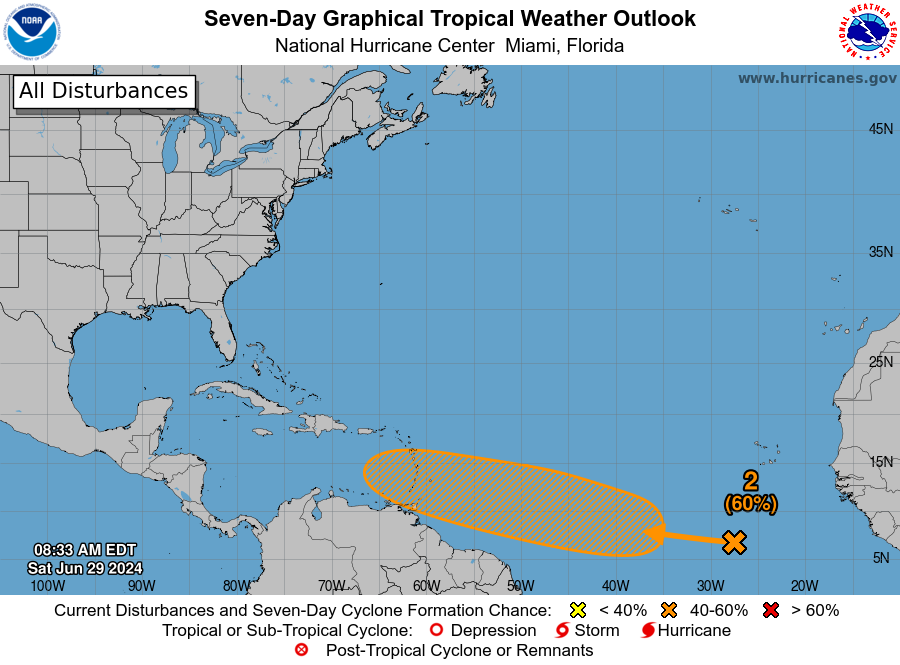

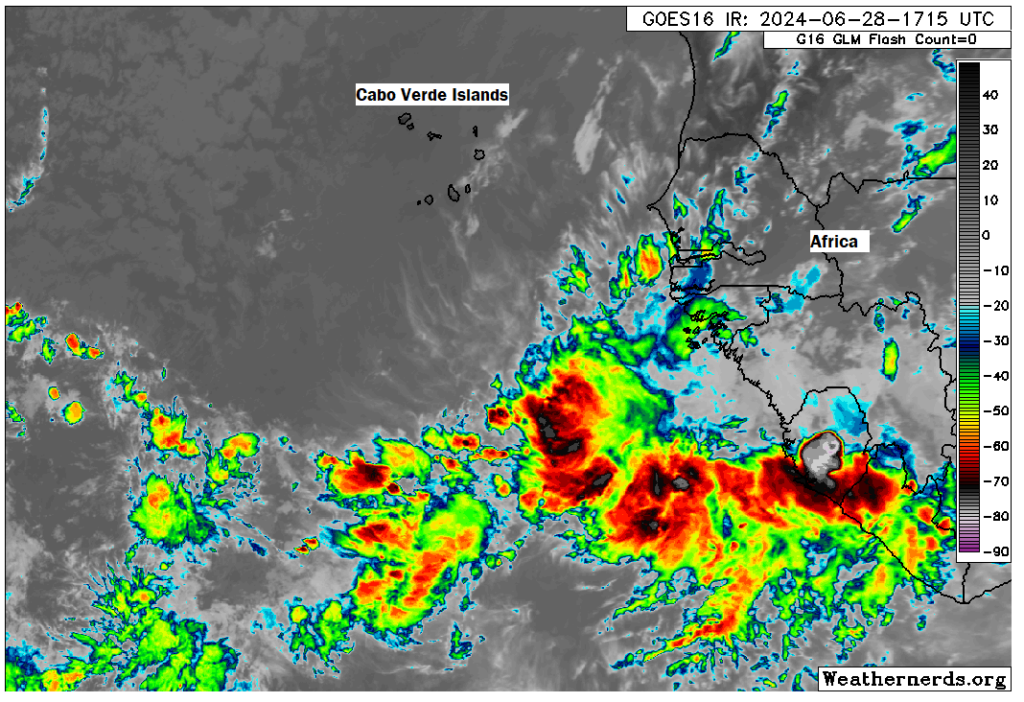

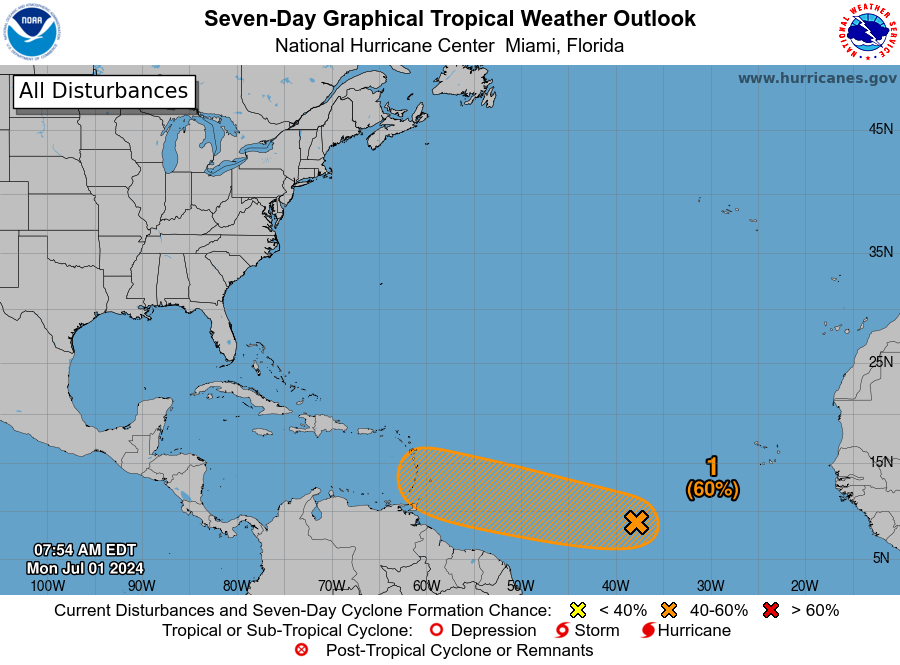

Behind Beryl, we continue to track Invest 96L. Models support a slow, gradual intensification of 96L as it essentially follows Beryl’s wake. Slightly cooler water will likely aid in that slower pace of growth. The National Hurricane Center is holding around a 60 percent chance of development with 96L, but it’s far too soon to speculate on exactly where it goes, short of it will follow close to Beryl’s track. What we’re more confident in is that slower pace of intensification.

Some good news: Once 96L exits the picture, we are expecting the Atlantic to settle down into a bit of a July lull (or so we hope). But model guidance keeps any real hint of anything absent in the Atlantic, Caribbean, or Gulf beyond 96L right now. Fingers crossed so we can catch our breath before August.