10 AM Wednesday update: PTC 1 is now Tropical Storm Alberto. We will have an update early Wednesday afternoon on the rain and surge issues impacting the Texas coast.

Headlines

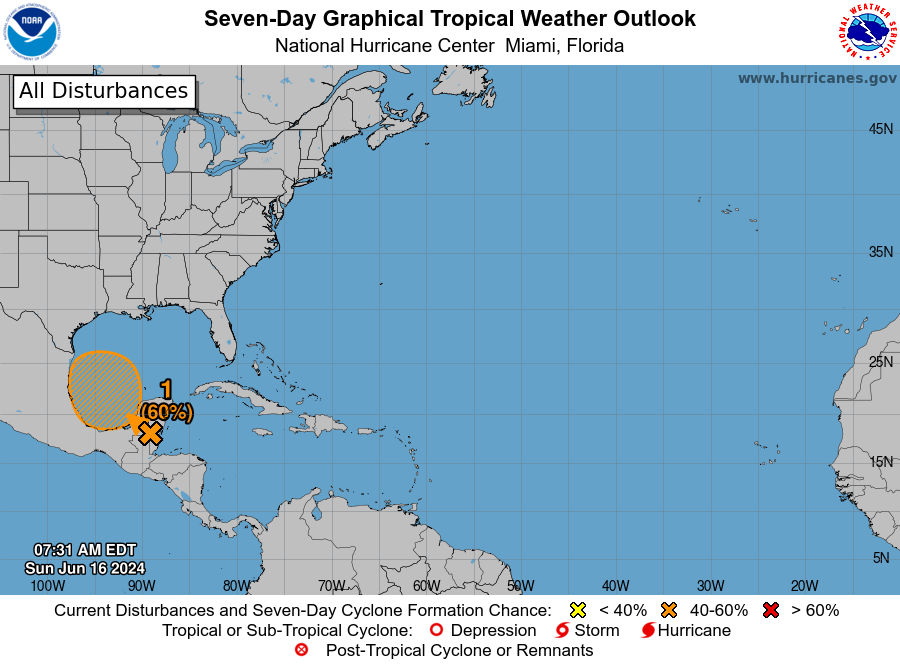

- Potential Tropical Cyclone #1 to bring marine impacts and heavy rain to portions of Mexico and Texas over the next couple days where flash flooding is quite possible.

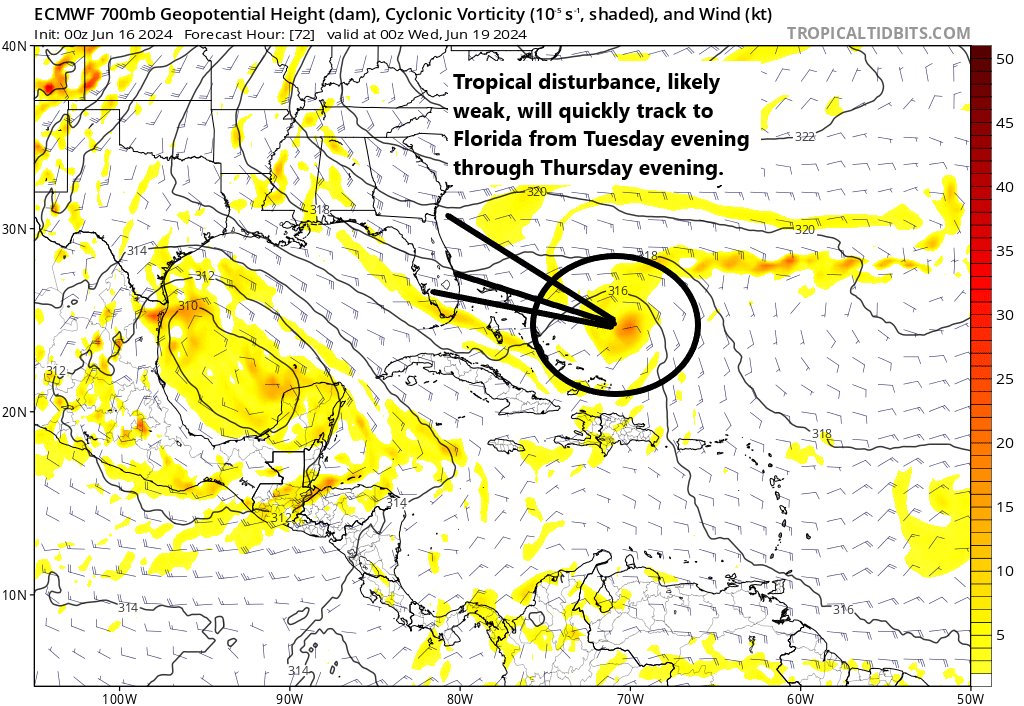

- Atlantic development remains fairly unlikely east of Florida, but some additional rain chances may arrive there this weekend or next week.

- A second system, perhaps very similar to PTC #1 will track toward the Bay of Campeche Sunday or next week, bringing additional heavy rain chances into Mexico and/or Texas.

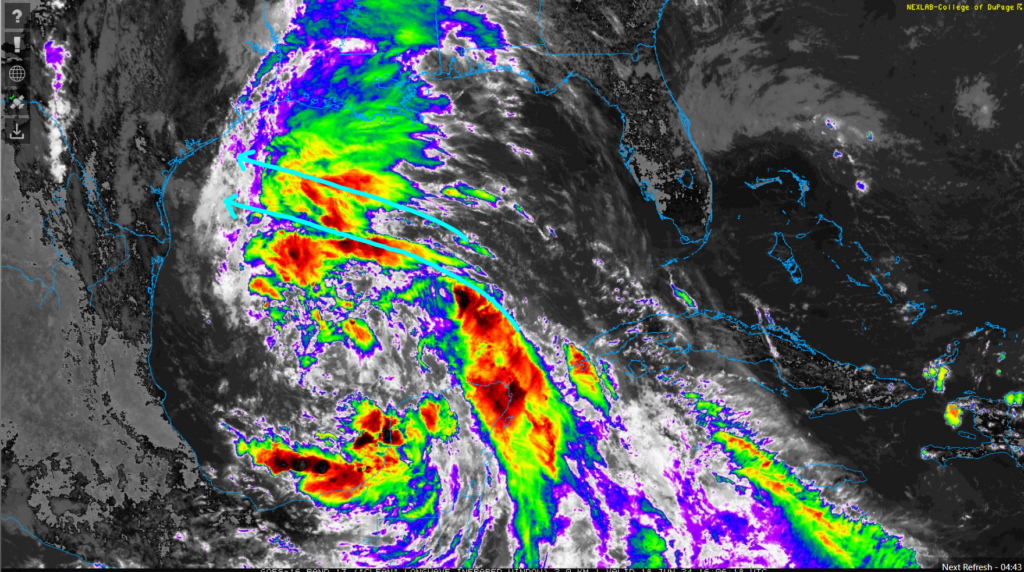

PTC #1 brings the rain tonight and tomorrow to Mexico and Texas

Late yesterday, Invest 91L was given the tag Potential Tropical Cyclone #1. Why? The National Hurricane Center needed to issue watches for a system that had not yet developed into a technical surface low and had winds of tropical storm strength. Basically, it’s their way of saying “We need to alert on this storm, but it hasn’t met meteorological criteria for formation yet.” From an impacts and what you experience on the ground standpoint, little has changed since yesterday.

We still expect this system to move ashore in northern Mexico sometime tomorrow evening. It will deliver a variety of impacts to Mexico and Texas, including coastal flooding (also in parts of SW Louisiana), rough seas, and gusty (but likely not damaging) winds. Scattered power outages in South Texas can’t be entirely ruled out, but they would likely not be severe.

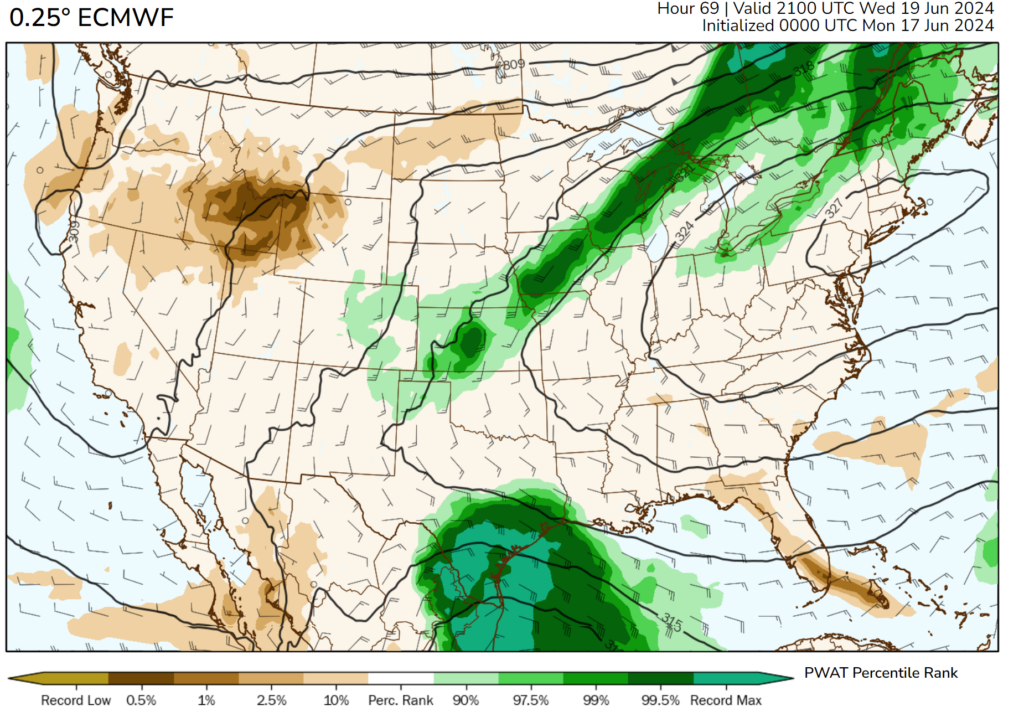

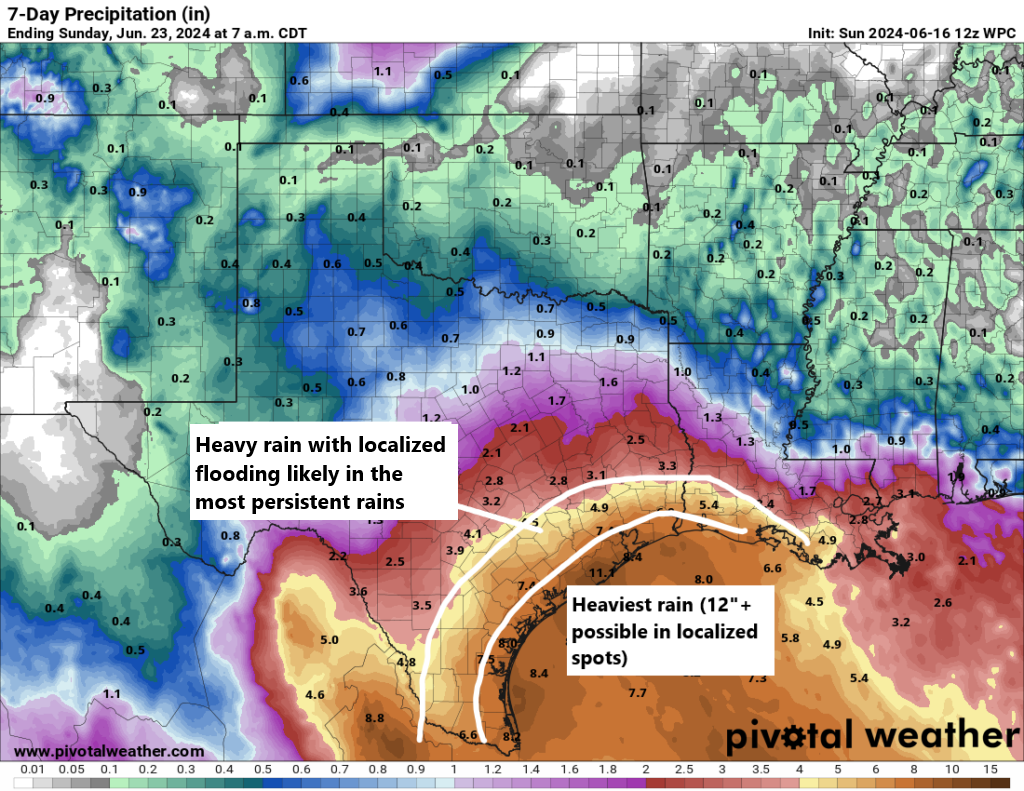

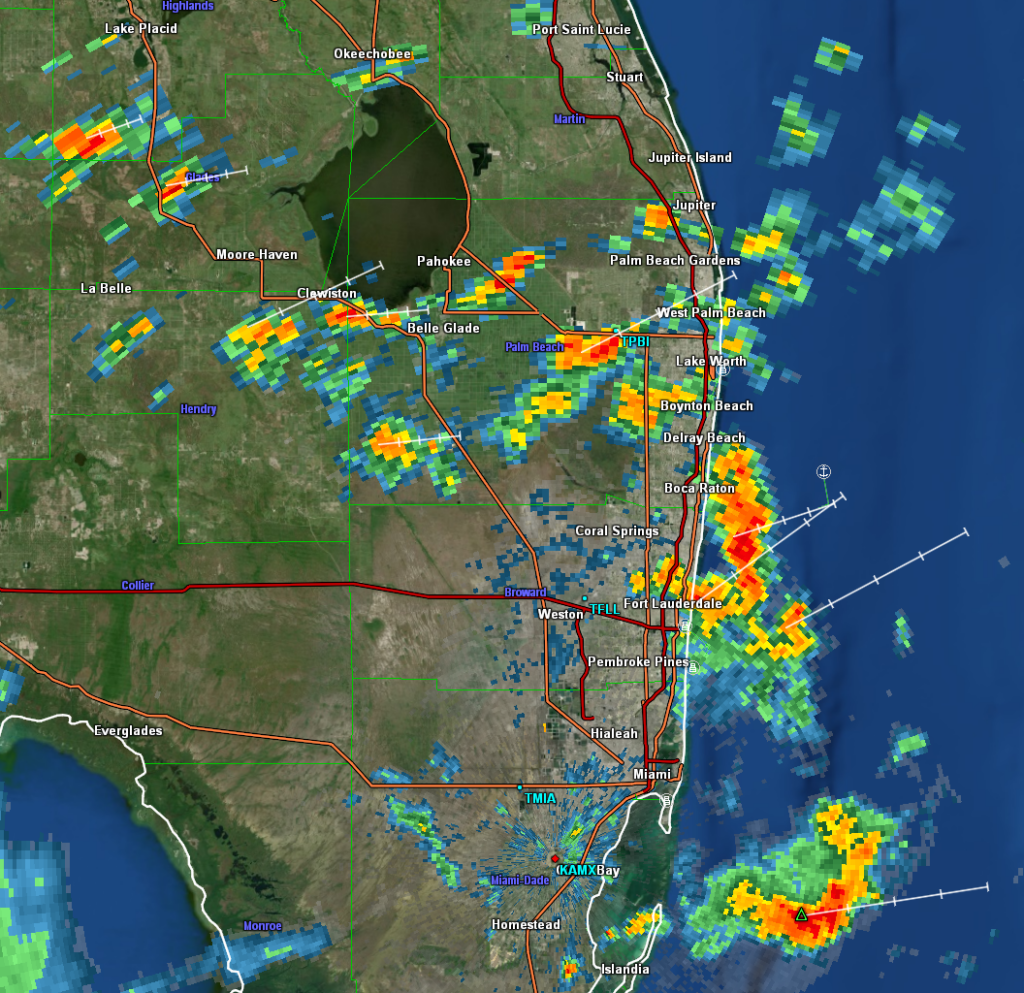

But the main thing I think to watch with this system will be the rain. Rain will push ashore in Texas and Louisiana later today and later tonight to the south into Mexico. Based on what we see on modeling and satellite this morning, it would seem that the heaviest rains will take aim to the south of Houston, more toward Matagorda Bay and eventually Corpus Christi.

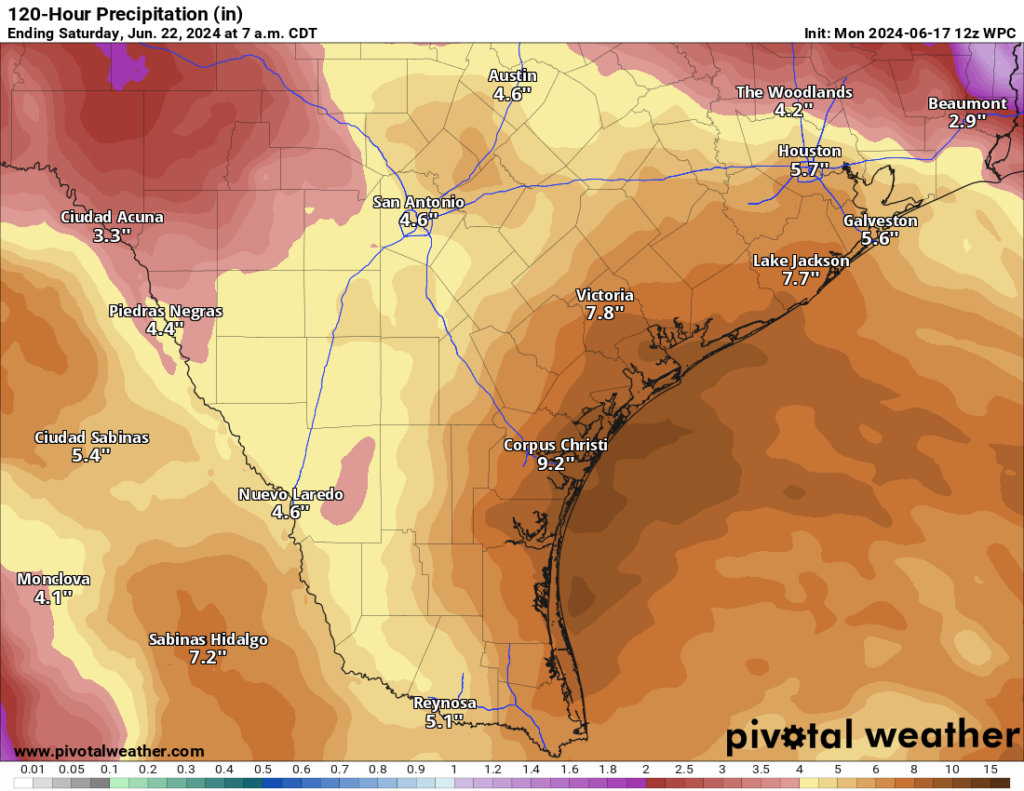

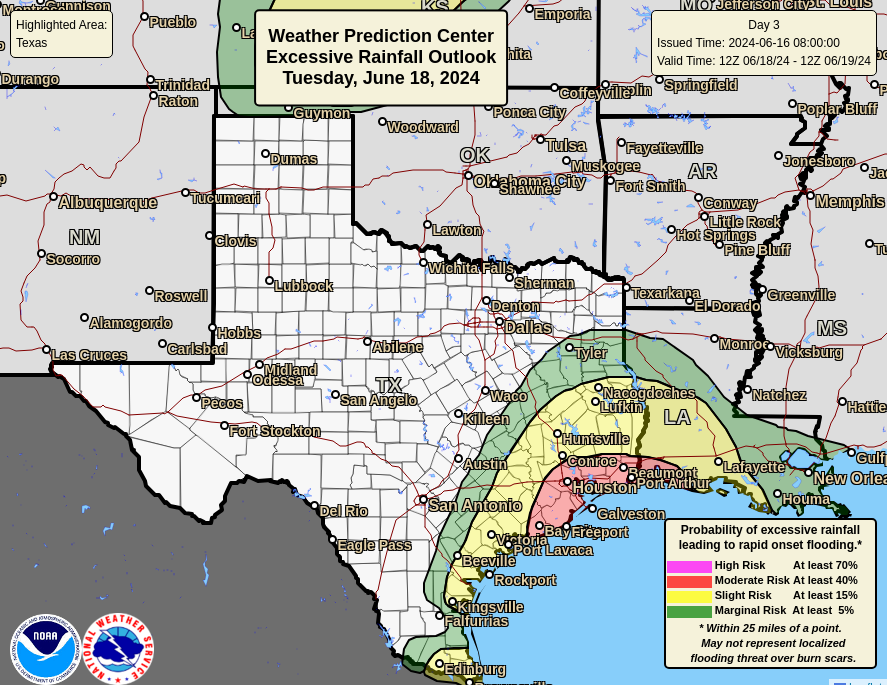

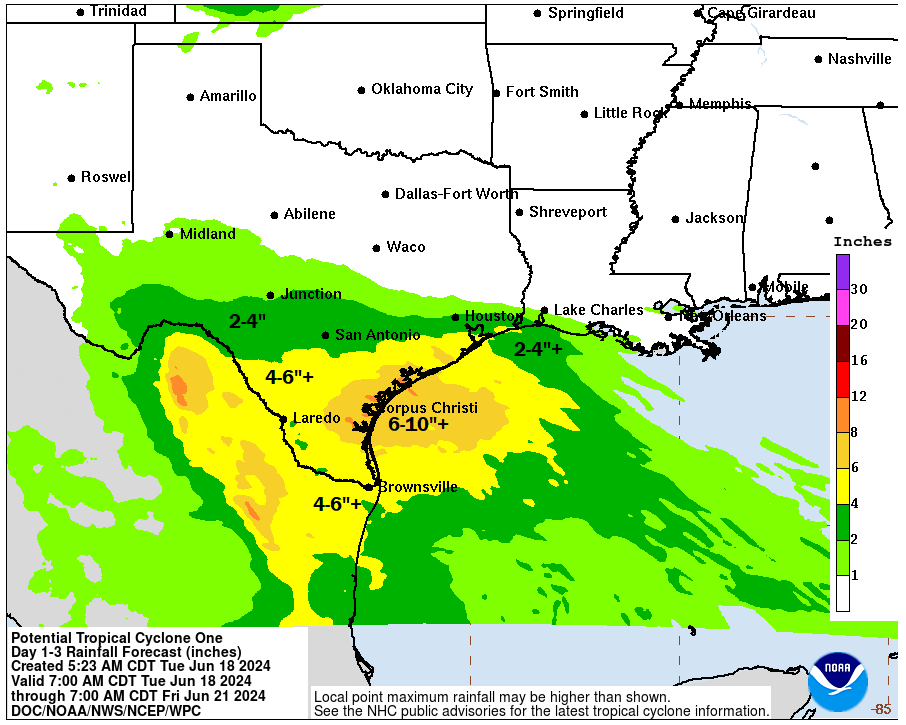

And indeed, this seems to be where modeling is rather consistently now focusing the heavier rain chances tonight and Wednesday. You can see from the rainfall map below that we’re expecting anywhere from 2 to 4 inches in the Houston area to 6 to 10 inches near Corpus Christi. I included the plus sign in my annotation on the map because the reality is that there will likely be embedded higher amounts anywhere in the entire region, depending on exactly where any banding features setup, a forecast that’s impossible to pin down more than a couple hours in advance.

Flood Watches are in effect for the entire Texas coast, RGV, and South Texas. Most of this rain will be welcome in interior Texas, where it has been quite dry. The rain in Mexico will hopefully be manageable, but as always in the mountains, we’ll need to watch for mudslides. Some fairly intense rain is also possible on the southern periphery of PTC 1’s circulation, delivering heavy rain to Central America, including 16 to 20 inches (400 to 500 mm) to portions of El Salvador and Honduras.

Travel tomorrow may be difficult across South Texas, so expect to run into delays or flooded roads. Conditions will improve a bit on Thursday and especially Friday. For the latest on Houston conditions, visit our Space City Weather site.

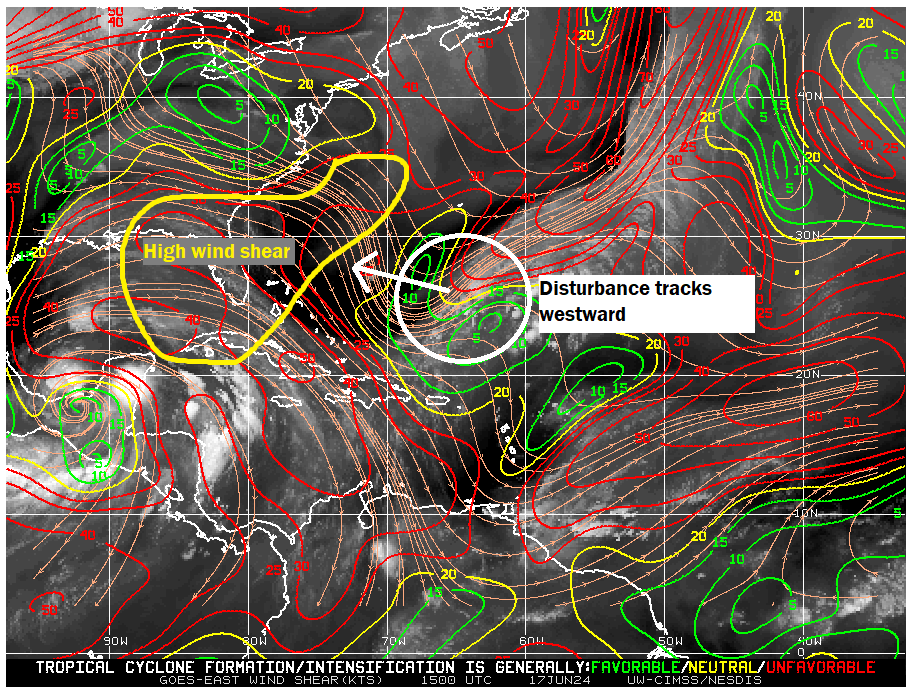

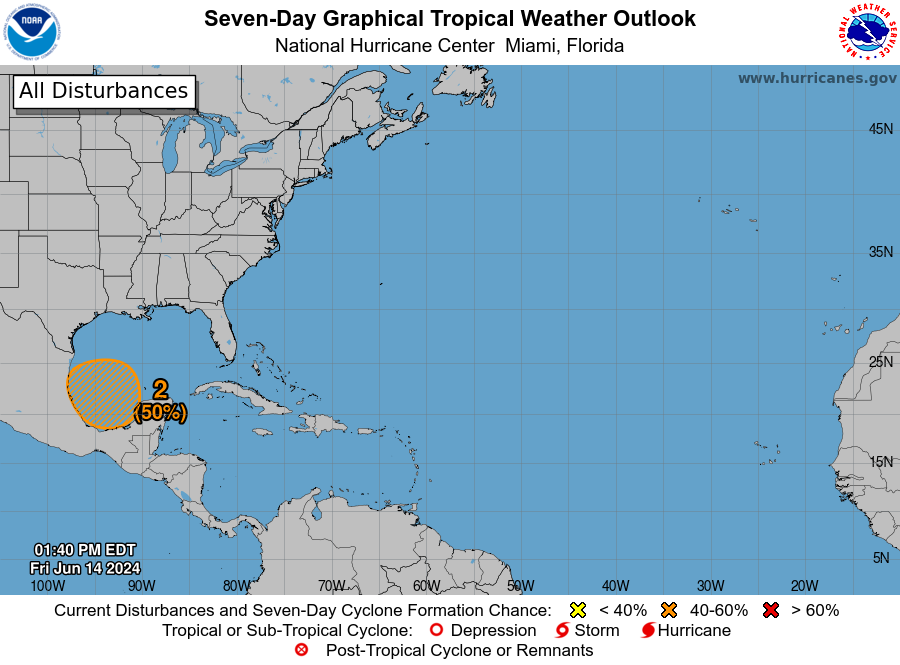

Southwest Atlantic system

Meanwhile, we continue to keep tabs on the disturbance in the Atlantic that the NHC gives about a 20 percent chance of developing over the next week. This one is likely to be a nothingburger for the Southeast and Florida and may just serve to elevate rain chances a bit this weekend or next week.

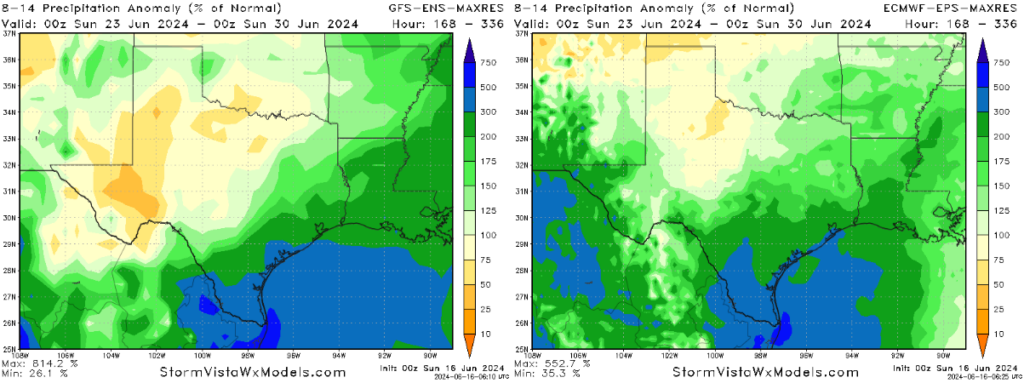

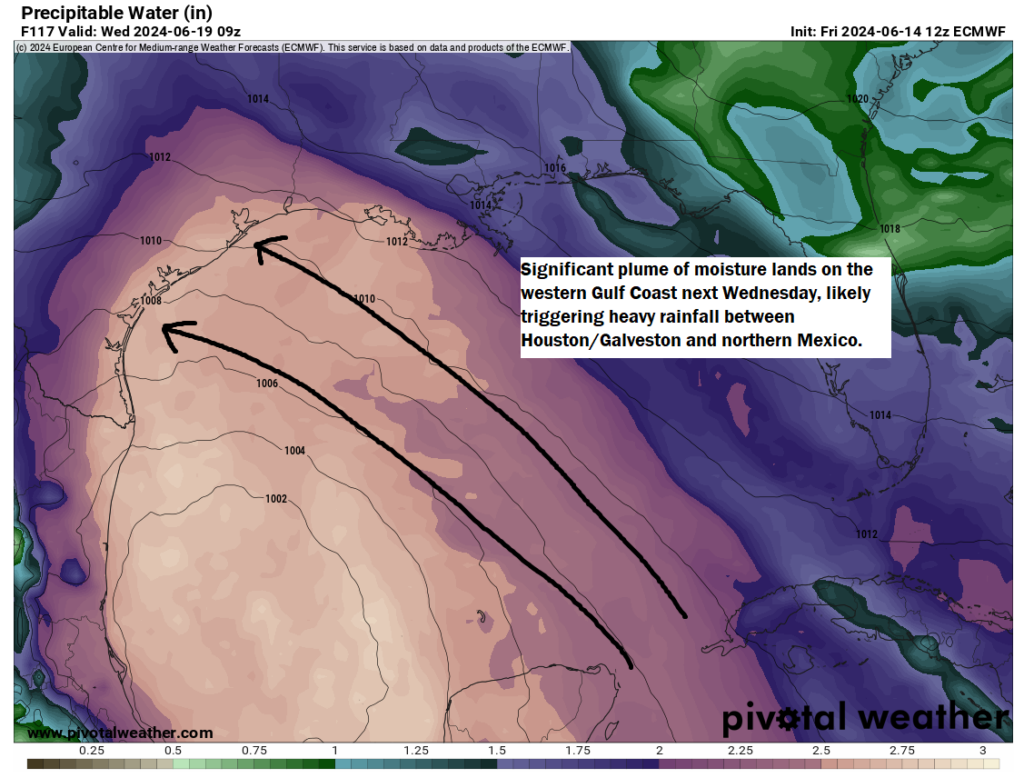

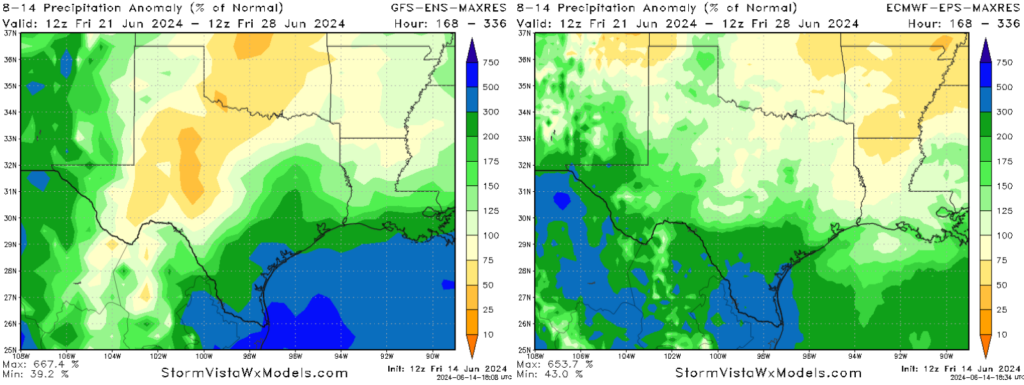

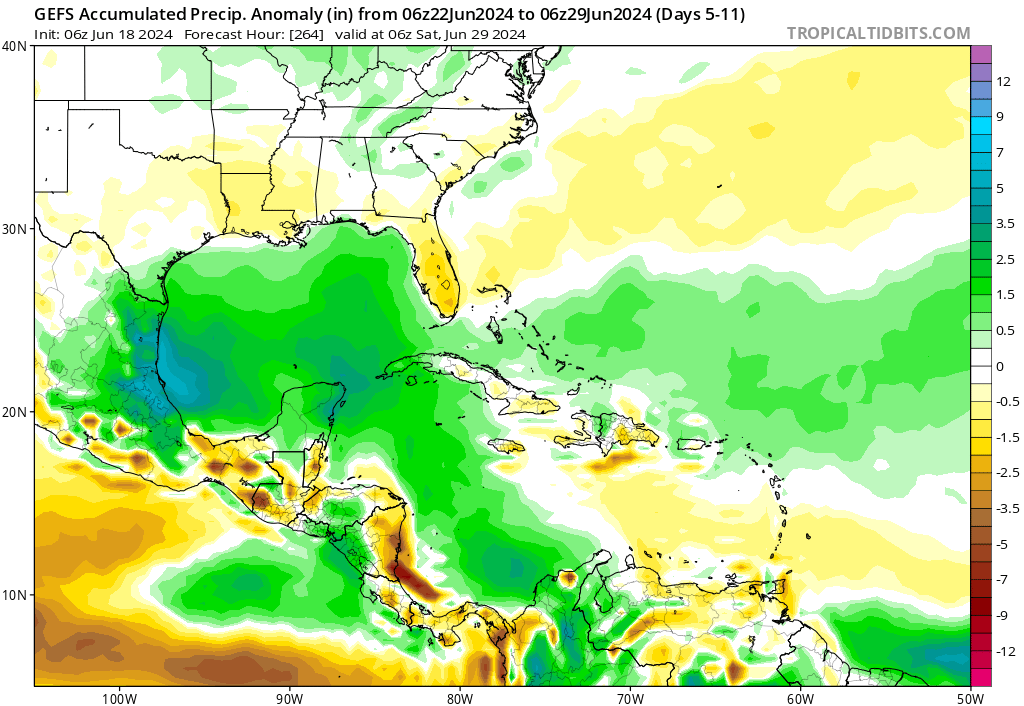

Southwest Gulf of Mexico: Take two

As we see PTC 1 exit late this week, quieter weather will build into the Texas and Mexico coasts, with just some isolated to scattered daily thunderstorms. But then by later in the weekend or early next week, we may get almost a carbon copy of this system: Likely lower-end in intensity, moisture-laden, and tracking toward northern Mexico. The problem will again be rainfall I think. While much of the rain from PTC 1 is welcome and will soak in, if a second system follows suit, the math gets a little more challenging.

Currently, the heaviest rain is expected to fall just south of where PTC 1’s rains will hit hardest. However, it is far enough out in time and with enough uncertainty to think that we will see things change with this. Interests along the lower Texas coast and in Mexico will want to monitor the next system’s progress closely, particularly with respect to the rainfall outlook. We’ll keep you posted.

Elsewhere, things look fairly quiet with no other systems of note at this time.

Don’t forget to follow us on your favorite social media platforms. We are occasionally posting videos and will link to our posts. If you wish to subscribe via email, the link to do that is on the right side of this page near the top.