One-sentence summary

With the historical peak week of hurricane season upon us, we take a look at what has happened so far, how seasonal forecasts have performed, and what we can glean for the rest of hurricane season based on the active start and El Niño.

How are those seasonal forecasts holding up?

Back in June when we launched The Eyewall, one of the things we did was dive into the components of the seasonal forecast. We explained that the 2023 hurricane season would be trickier than normal, as the developing El Niño, which typically reduces storm activity would be battling an outrageously warm Atlantic Ocean, a feature that would be good for busy storm activity. So far, that battle seems to be exactly what’s playing out. The “consensus” forecast was 16 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 majors. As of Monday, we sat at 12 named storms, 3 hurricanes, and 2 majors.

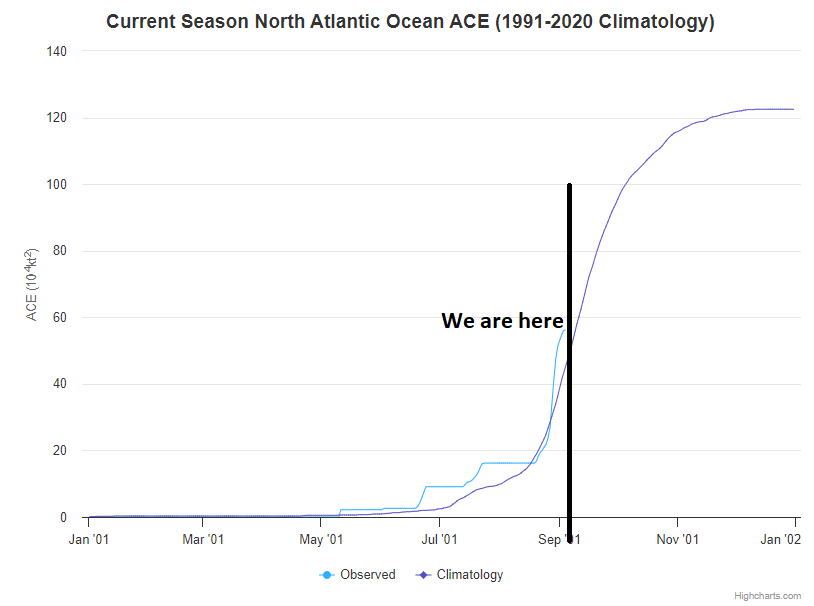

Our accumulated cyclone energy for the season, or ACE, sits around 125 percent of normal for the first week of September.

If the season ended right now, we would be sitting in the upper tier of “below normal” seasons. In other words, we already have one heck of a base and seem to be on our way to (at worst) an average season. The seasonal forecasts did a good job telegraphing this, and frankly some of the more active seasonal forecasts that I believed were more out of an abundance of caution are the ones most likely to verify.

And this isn’t because of ticky-tack storms that last a day or two. Idalia, Don, and Franklin, the three hurricanes account for nearly 75 percent of the seasonal ACE to date. So three legitimate storms make up the majority of the total. Back in June we said that we believed the Caribbean would struggle (it mostly has), the eastern Atlantic would be busy (it’s been more the central Atlantic, so that point is a little fuzzier), and that the most concerning items this season would be systems forming close to home (Idalia counts for that). So thus far, this is going mostly as expected, if not a little bit busier. Kudos to the seasonal forecasters for not just going all-in on El Niño.

Where are we going?

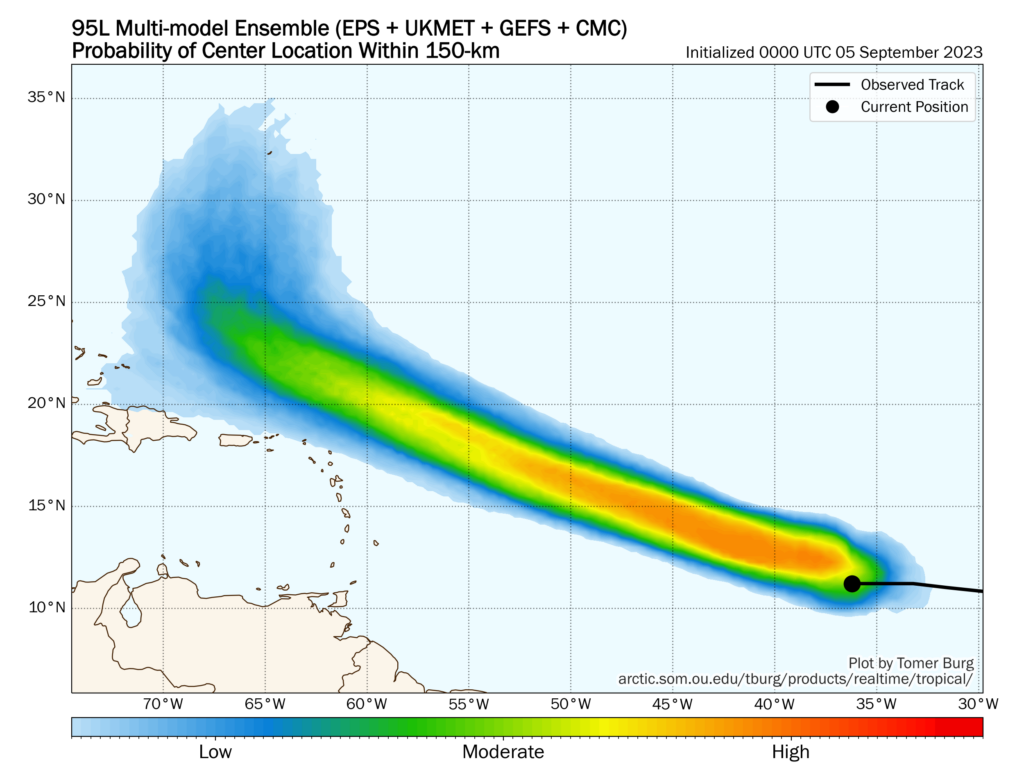

Well, this week we are likely to see another big jump in seasonal ACE when Lee forms.

From our morning post, you can read how we expect that to become a major hurricane, likely at least a category 4 storm. This will be a big ACE adder, and I suspect we’ll see things shoot up at least into the 70s once Lee is done, pushing us into the “average” tier of seasons if it ended right there. Behind Lee, we may get another storm in the eastern Atlantic, so there’s an opportunity for a few more ACE units.

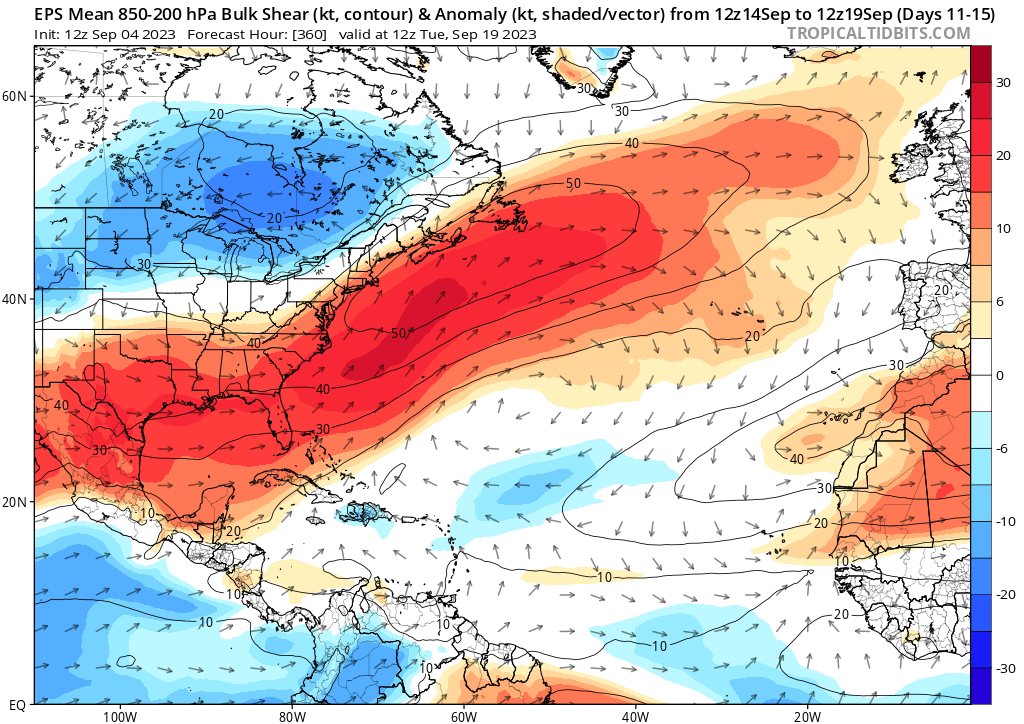

But here’s something. If you look at the European ensemble model forecast for wind shear in days 11 to 15, which pushes us out to near September 20th now, you can see that the Gulf and western Atlantic are ripping with shear.

If that happens as forecast, anything in the Gulf will struggle, as would anything coming out of the Caribbean. However, the lower wind shear in the eastern Atlantic and central Atlantic suggests these would be the areas where storms could continue to form, continuing the legacy of the 2023 season to date. We may see less hostile conditions return to the Gulf and western Atlantic in the final days of September, but that’s obviously a long way off.

What does El Niño tell us?

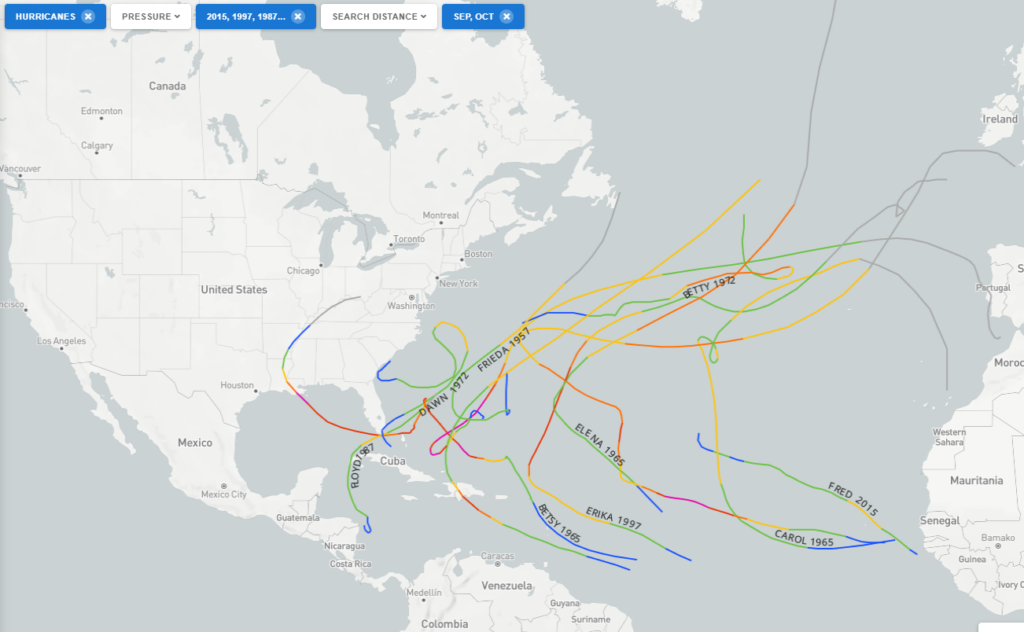

Quite frankly, if we assume that El Niño is up and humming now and the influence is strengthening, then we should expect to see a lot of what we’ve already seen for the remainder of hurricane season. Here is a map of all hurricanes in Septembers and Octobers since 1950 when the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) was 1.0 or greater for June-July-August (this year’s value is 1.1).

With a couple notable exceptions, this map shows a lot of fish storms and middling systems in the western Atlantic. The two most notable exceptions were Joaquin in 2015 which killed 34 people (33 of whom were aboard the El Faro). And also Betsy in 1965, which killed 81 and inundated New Orleans. Emily in 1987 hit Hispaniola and Bermuda. And I think that sums up the season so far: A lot of middling storms and mostly fish storms with one potent hit in Idalia.

All in all, given what we see on the maps right now and given how this season has gone, there are two primary areas that probably should watch for land impacts: Bermuda and the Greater Antilles. If we can relax shear enough late in the season and get a disturbance in the Caribbean that comes straight north, you never know what you can get out of that, and those often threaten Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola or the Bahamas. Bermuda remains in the target line I think for at least one or two more storms. Lastly, the eastern Gulf or off the Southeast coast may be secondary areas to watch, given the warm waters and potential for just the right things coming together at the wrong time, sort of like what we saw with Idalia and to a far less impactful extent, Harold in Texas earlier this season.

Will it be enough to drive ACE above normal for the season in the end? I’m not certain, but it will be close.

this is a great information, Matt 🌿

tysm 🌬⚘

I agree with “cat”…lots of good info easy to follow and understand…great work, Matt…thanks!

Thank you for your insightful assessment. Of course we never assume or let our guard down, this season’s pattern just doesn’t favor TX landfalls. As you explained, just a slight relaxation or change in patterns could bring a storm to us. The looks of things show that we are less vulnerable than in other seasons. Nevertheless, we all appreciate you and Eric laying it down for us every day.

Is it possible to remove wind shear as a variable from 2023 to date and revise how many storms and hurricanes we would have had without wind shear?

It’s an interesting research experiment. My hunch is going to probably be surprising, but I am going to hypothesize that the answer would be “not many” other storms. I think dry air or a background state of sinking air has been more of a problem this season than wind shear, which is odd in an El Niño season. But I think we may be seeing the Niño now flex and maybe we could run this experiment on the back half of the season and get some different results.

The CFS Weekly is showing some serious shear for weeks in the Gulf. It is showing upwards of 40 to 50 kts at the end of the month. It does seem like Texas can breath easier.

Another prediction that seems to have come true…..the GFS has performed poorly once again.

There really should be something like ACE that measures the energy for cyclones that impact the CONUS or Atlantic islands. Hurricanes that live their entire lives out in the middle of the Atlantic are of little impact (other than to shipping vessels). If all the hurricanes in a given season were humongous but never touched land, and therefore the ACE was at an all-time high, would the headlines of “Worst Hurricane season ever!” really mean much?

Almost like a population-weighted ACE or something. I’ve seen some attempts at this done by private entities. I’ve also seen other index values I like that tend to work better than Saffir-Simpson for intensity. There are absolutely better ways of describing the season as a whole or an individual storm. I think we use what sticks just because of index fatigue risks. But it would be interesting to weight ACE by population impacted.