A happy Father’s Day to those celebrating today! We’re here on Sunday with the latest for you on what continues to be an active June in terms of impacts.

Headlines

- Tropical development is very possible in the Bay of Campeche this week.

- Regardless, the pattern supports a very heavy rainfall threat for the Texas and Louisiana coasts into Mexico as well, with flash flooding becoming increasingly likely.

- A new disturbance may track toward Florida late in the week, but most impacts should be north of the areas worst impacted by last week’s rains.

- Another western Gulf system is possible after this week with more rain in Texas.

Potential for widespread heavy rain and flooding in coastal Texas

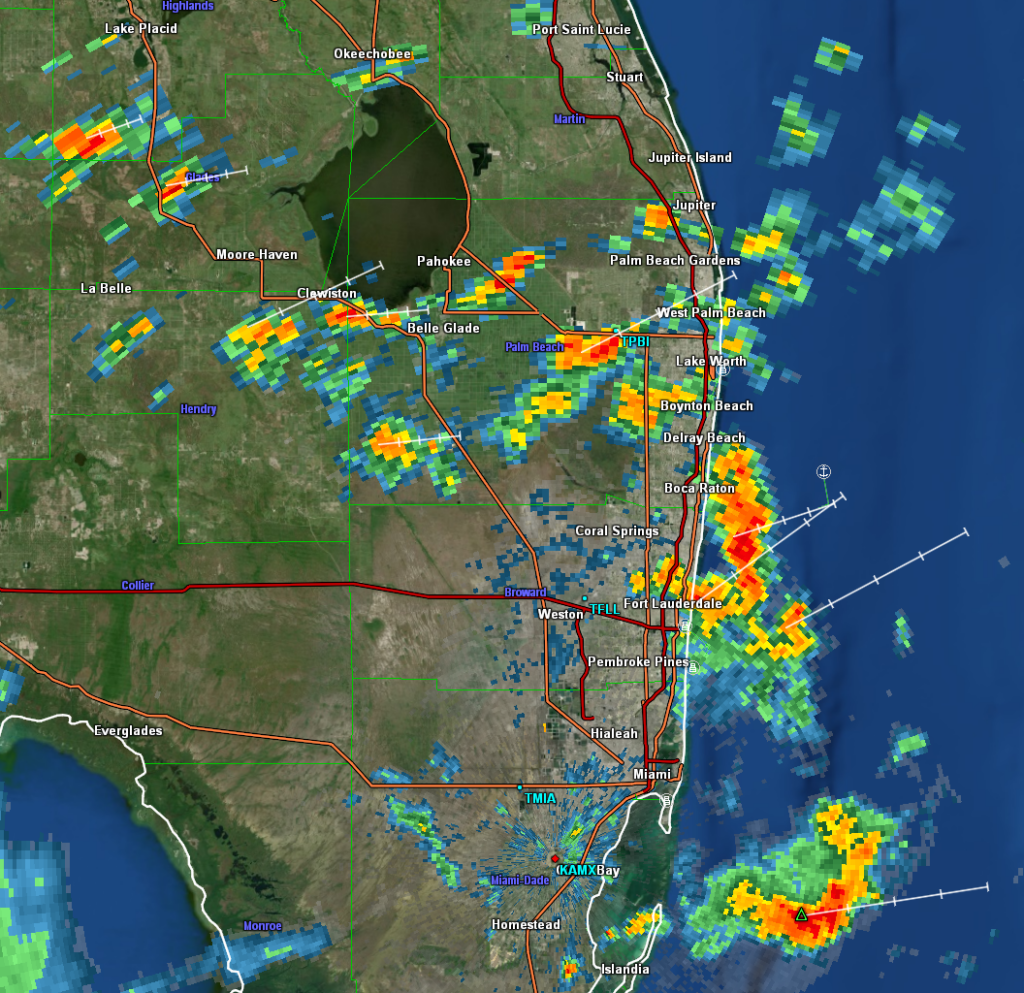

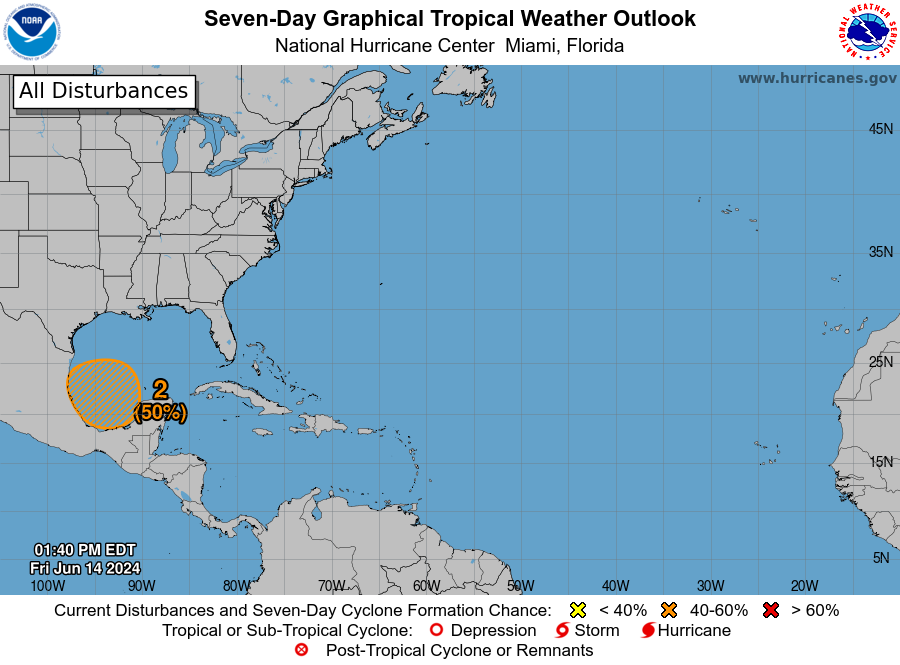

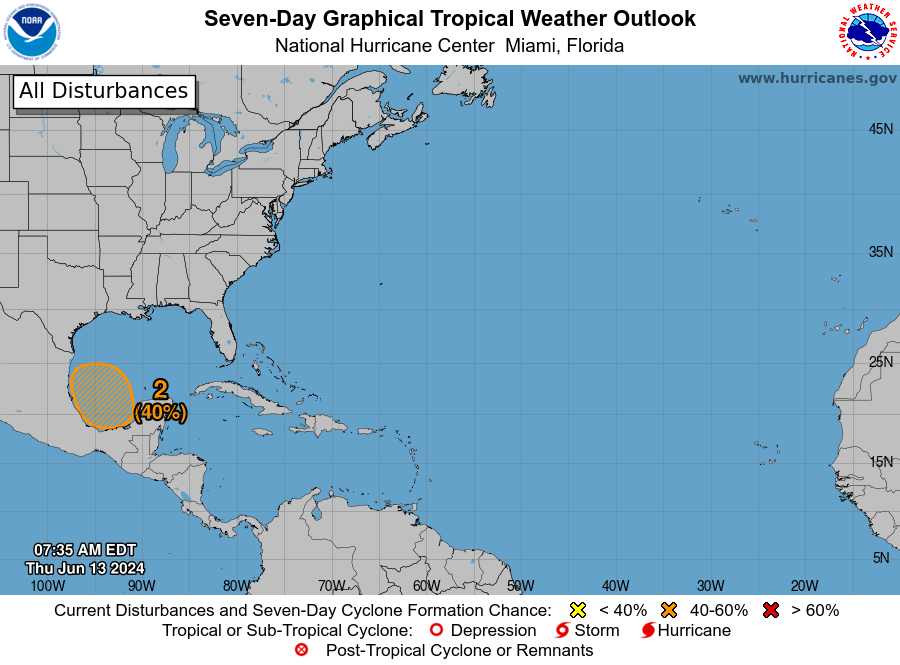

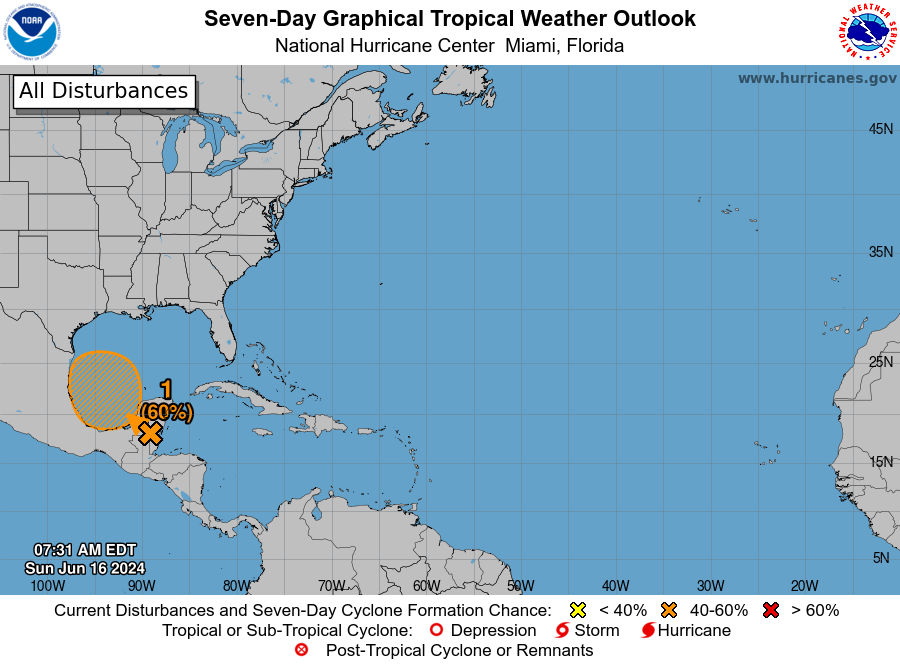

The main story from an impacts perspective this week will almost certainly be the situation in the western Gulf of Mexico. We are still monitoring the potential for development from a system in the Bay of Campeche this week.

The chances are fairly modest still, up to around 60 percent, and it would appear that any development should have a pretty low ceiling for intensity. The system should be inland over Mexico by Wednesday or early Thursday.

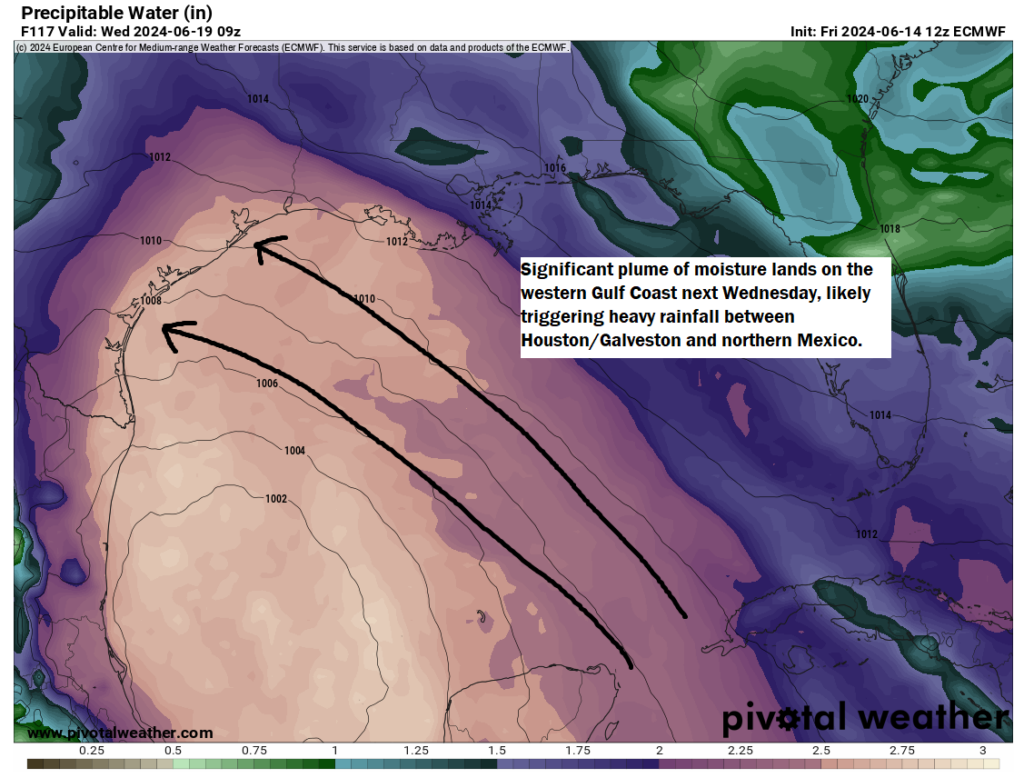

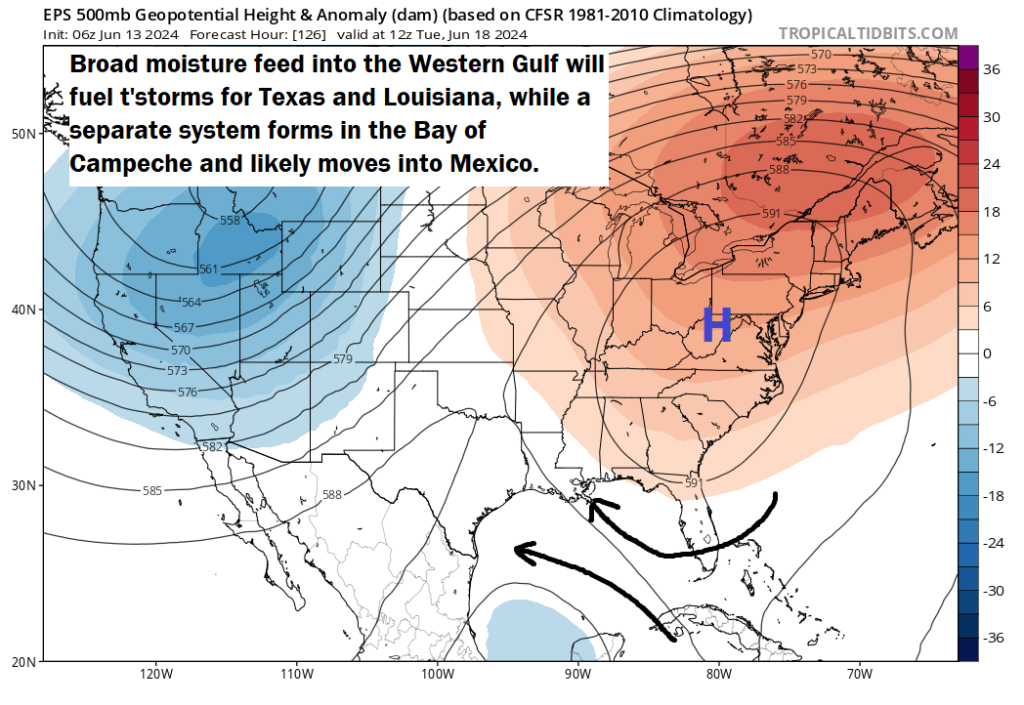

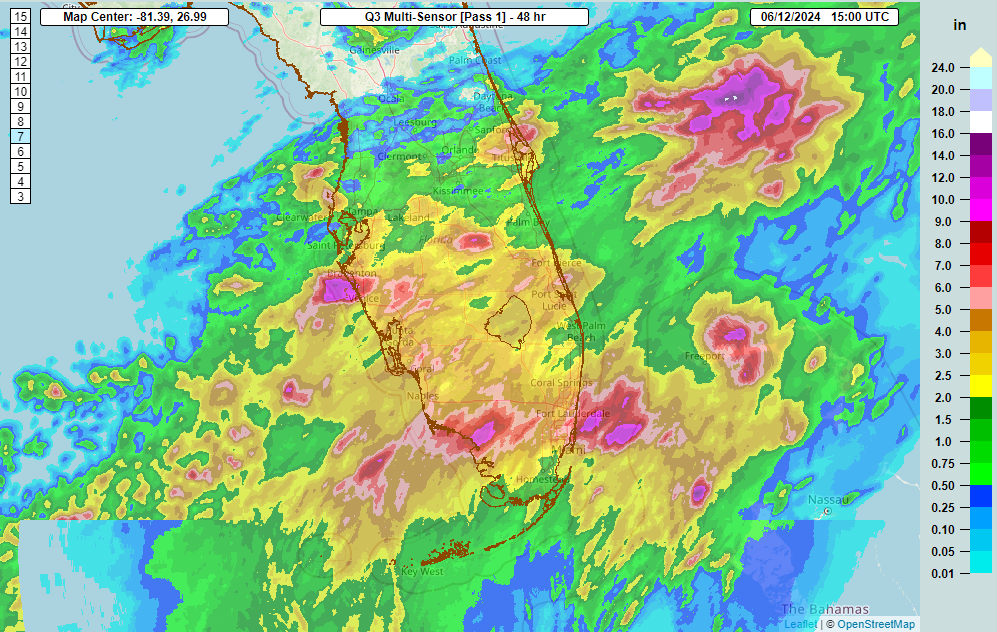

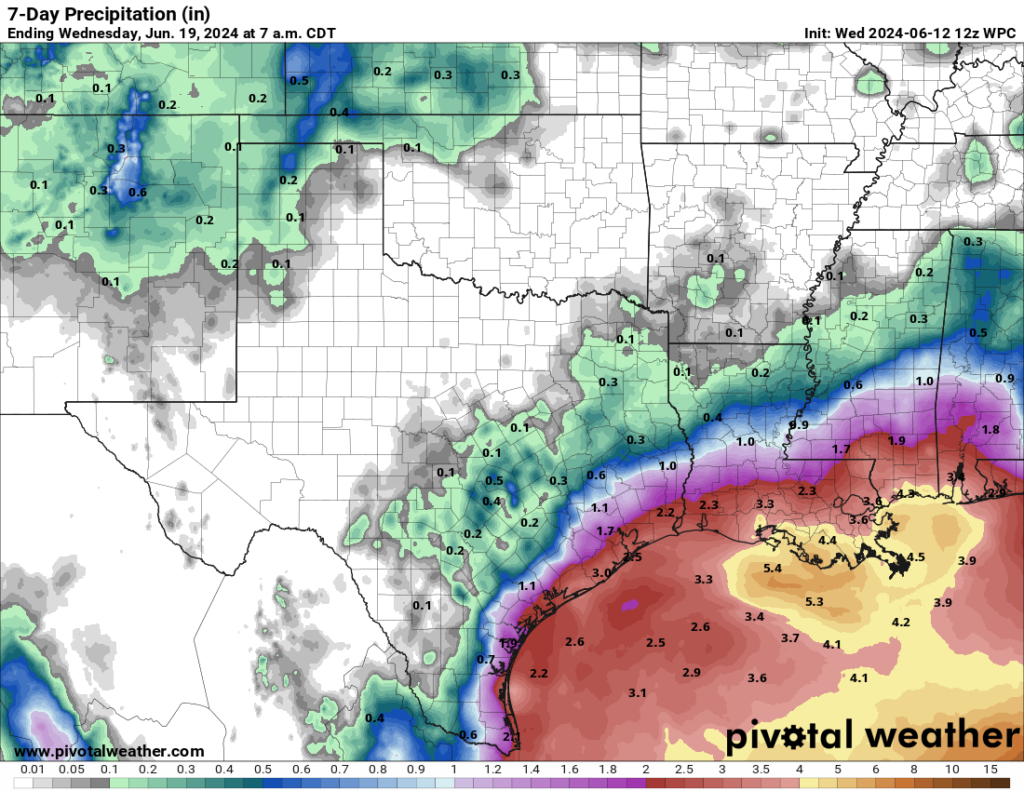

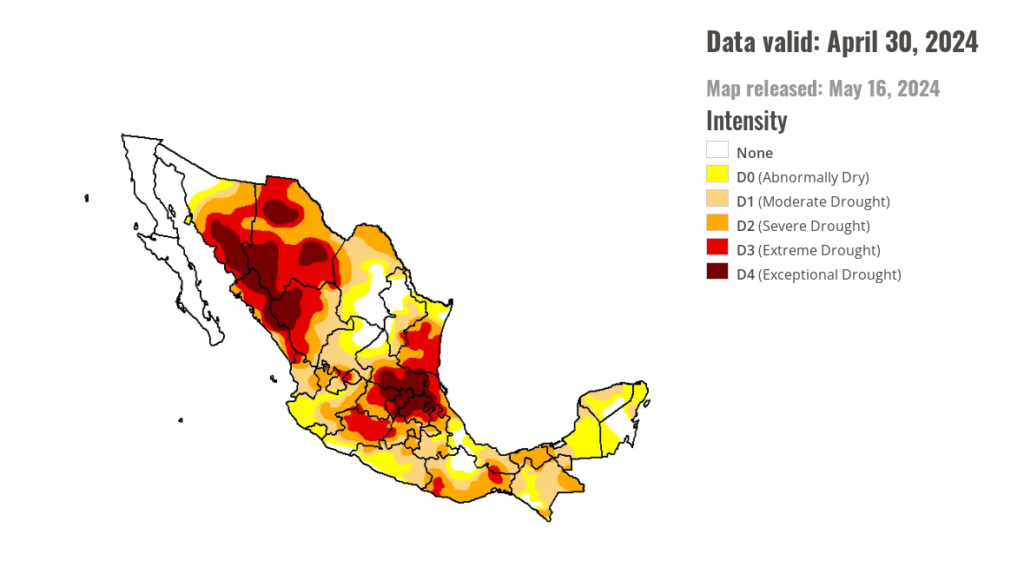

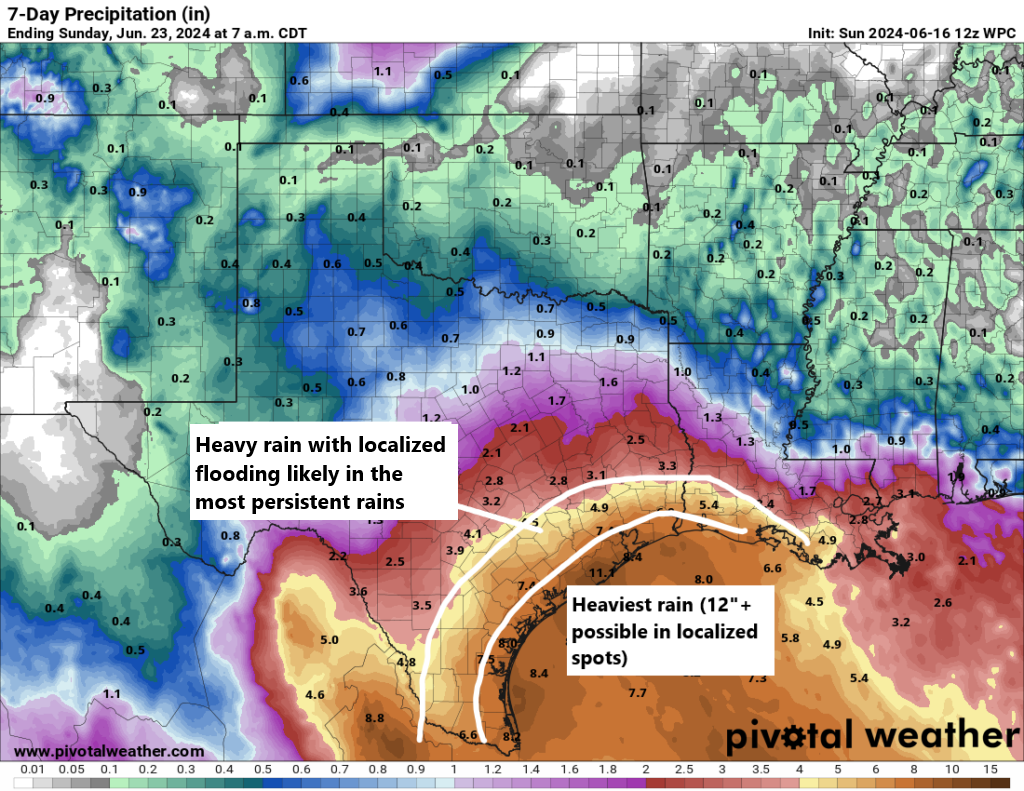

The problem is that the overall pattern into the western Gulf remains extremely favorable for heavy rainfall over a very wide area. Extremely deep tropical moisture will be pushing in over top of the tropical low that moves into Mexico. This will crash into Texas on Tuesday and especially Wednesday. The forecast for precipitable water, or the amount of moisture available in the atmosphere will be running near both daily historical maxes and potentially all-time record levels for the Texas Coastal Bend. This means that rain will be efficient and heavy.

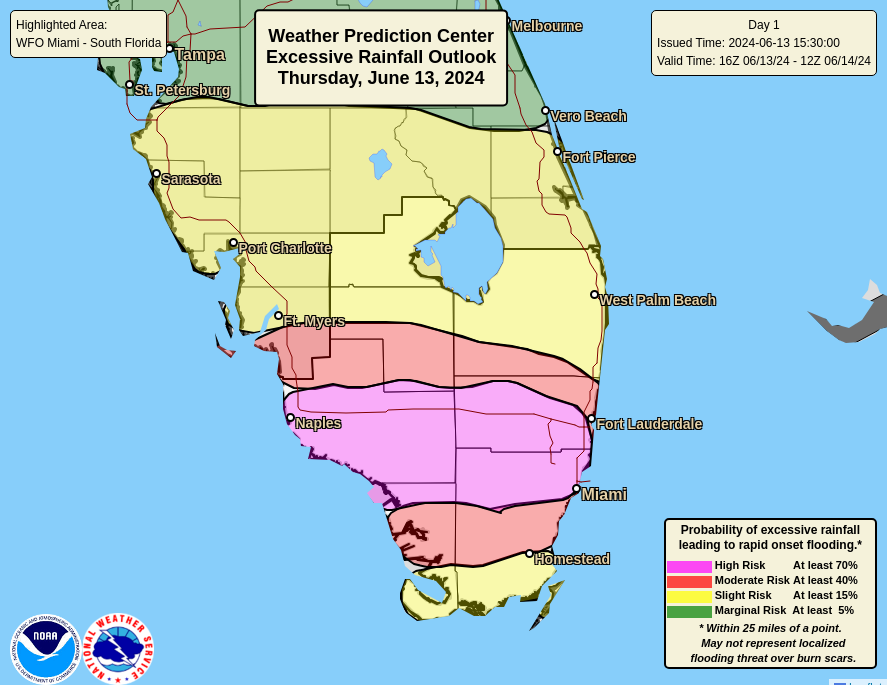

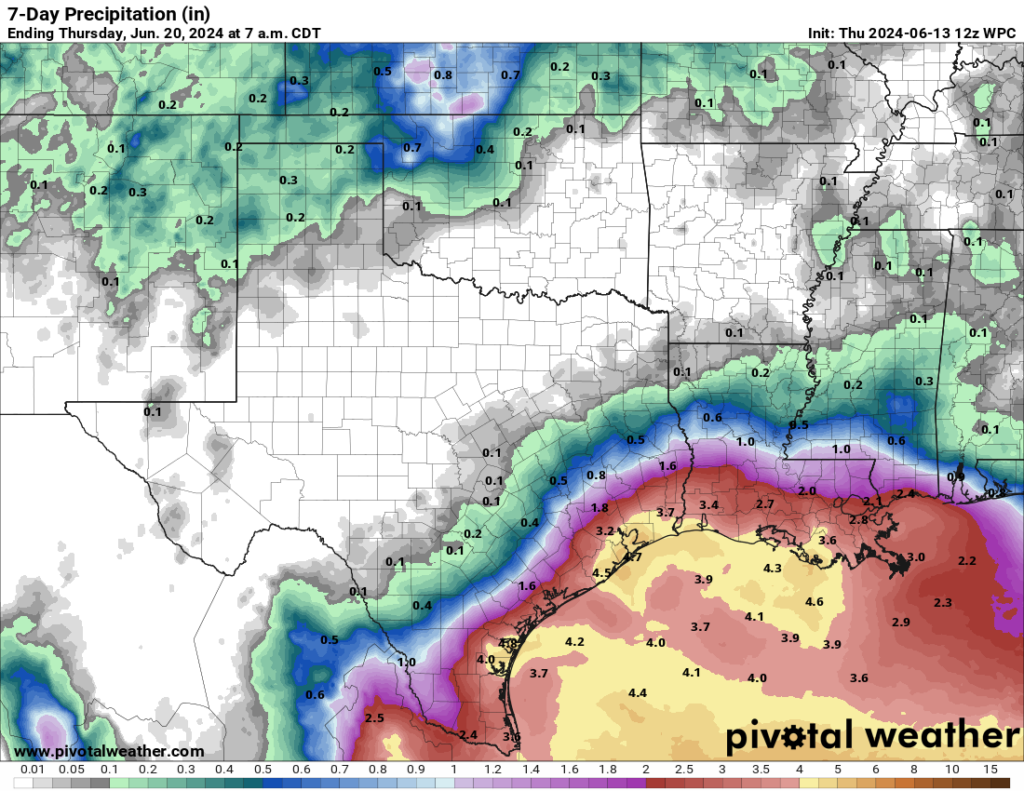

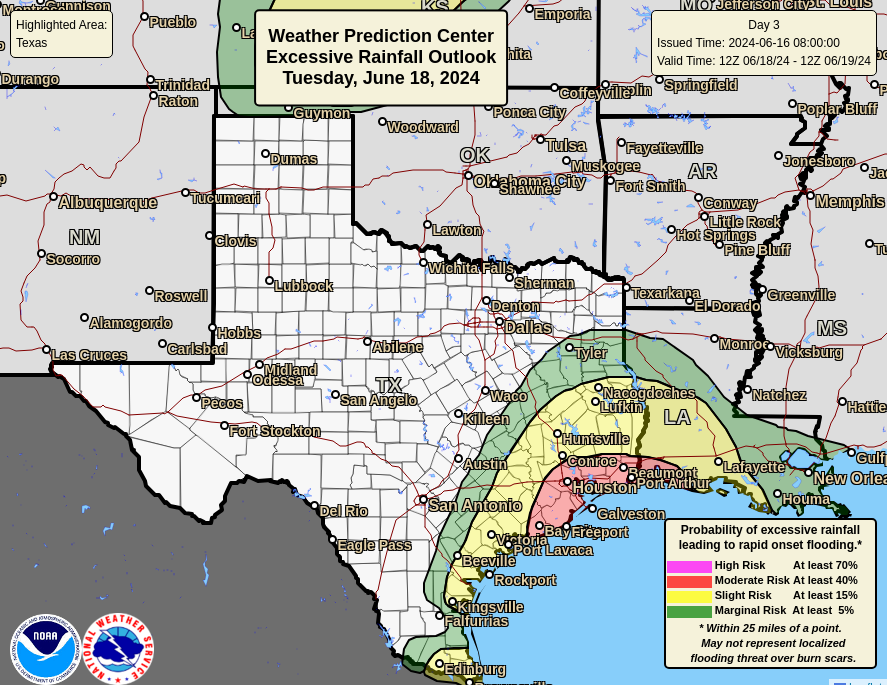

Rain totals have been escalating all weekend and it now appears that perhaps a foot or more rain may fall on the Texas coast. Lesser amounts are likely inland, but they will still be heavy, and it cannot be stated more plainly that flash flooding and potentially serious flash flooding is possible anywhere between Beaumont and Brownsville, depending on exactly where the heaviest rainfall orients.

A moderate risk (level 3/4) of excessive rainfall and flooding is already in place for portions of Texas and Louisiana on Tuesday, including Houston, Galveston, and Beaumont. Suffice to say, this is yet another example of potentially a low-end storm or nameless storm that can produce significant rain and flooding impacts. Folks in Texas and southwest Louisiana should monitor forecast developments closely today and tomorrow. Stick with Space City Weather for those in Houston for the latest.

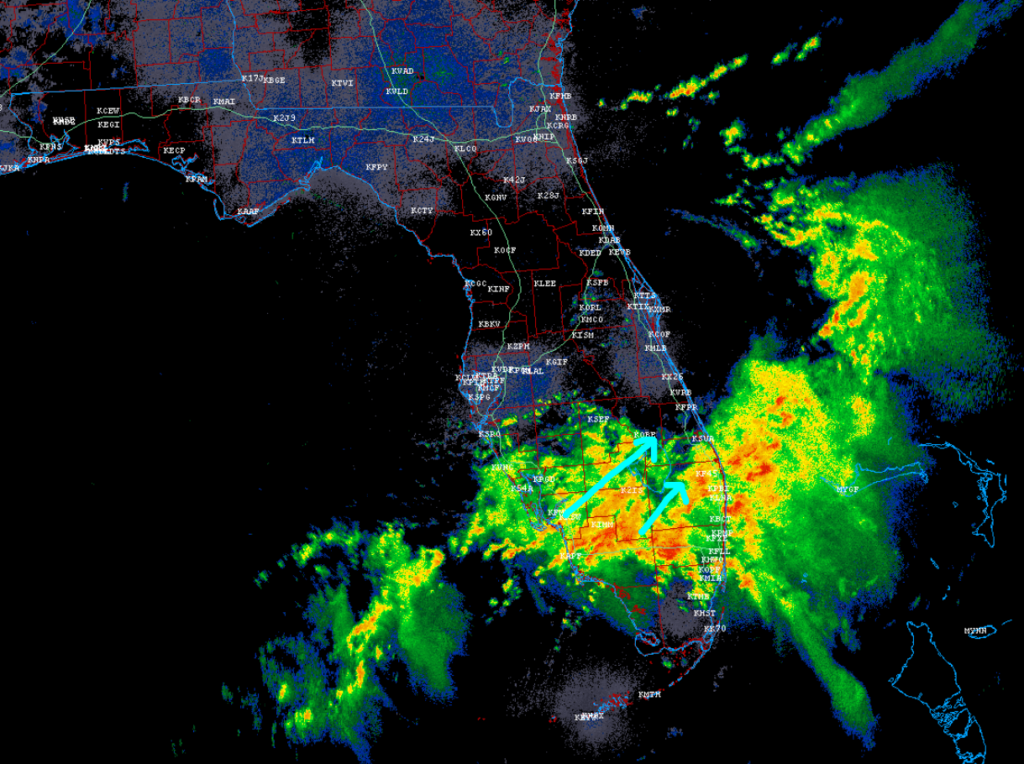

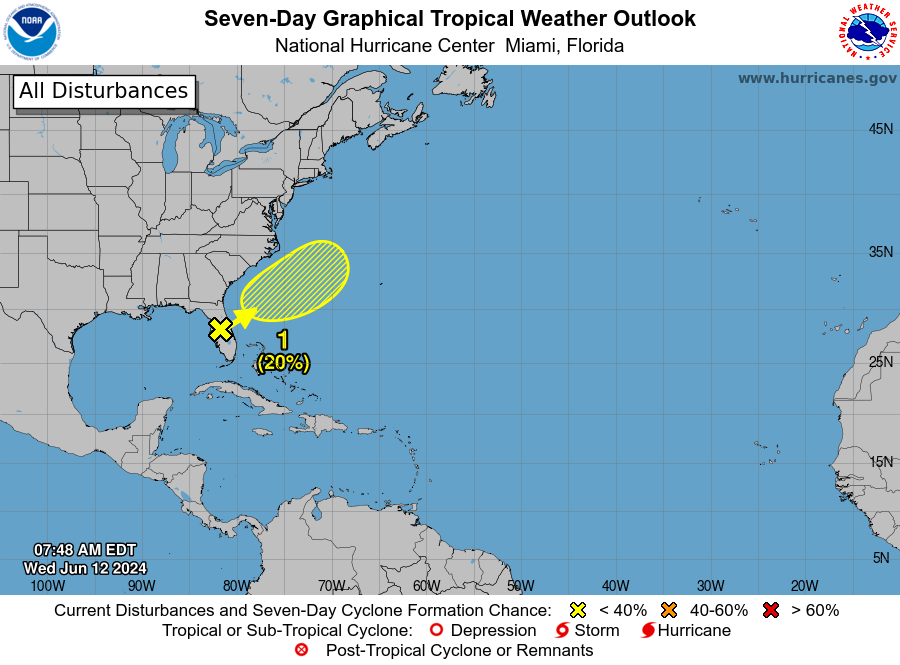

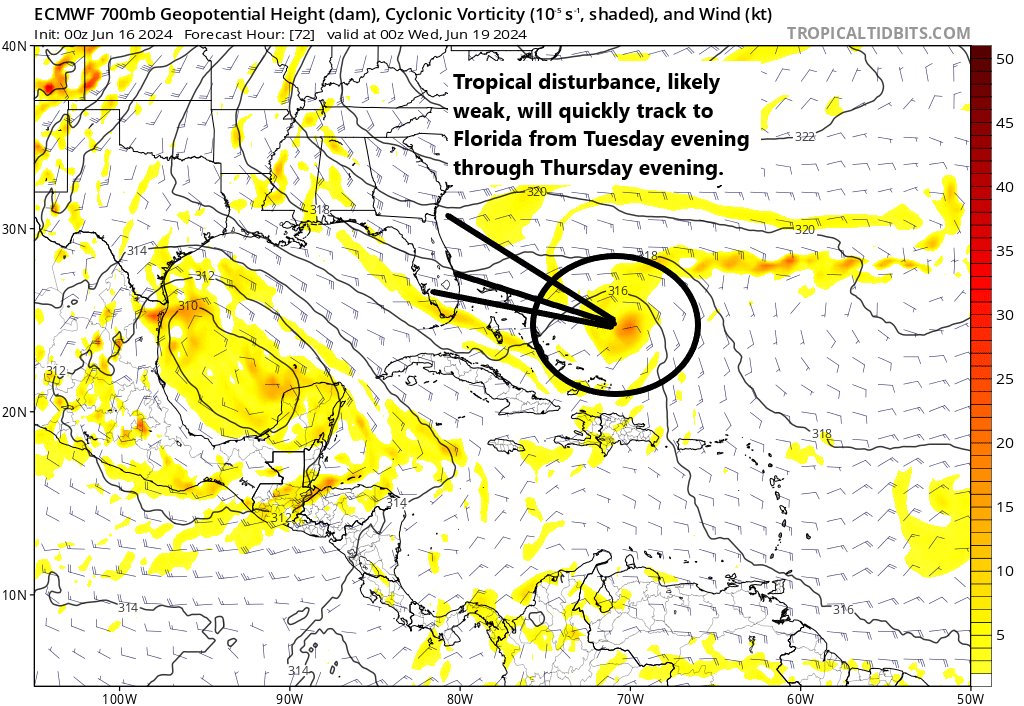

A new disturbance tracks toward Florida or the Southeast this week

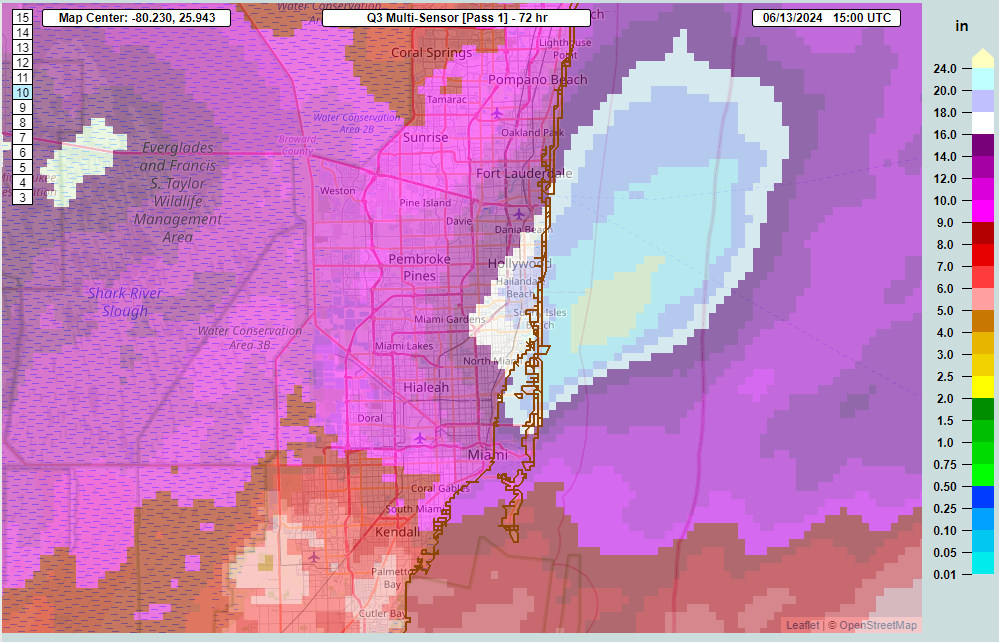

We left you on Friday with the idea that the focus would move to the western Gulf. What has changed since Friday is that a new tropical disturbance seems likely to form north of the Bahamas by Tuesday. The good news is that this will quickly track west, arriving in or near Florida by Thursday and eventually inland through the Southeast.

The NHC has a 30 percent chance of development with this one as it tracks west. It would seem that whatever forms will probably be lower-end in nature, but given the amount of rain that recently fell in Florida we’ll obviously want to watch this closely. At present, most model guidance seems to favor it tracking toward areas north of the Space Coast. In that case, South Florida will be fine, with most heavier rain falling toward Jacksonville, Georgia, or South Carolina. As always, it will be good to monitor things the next couple days just to make sure everything behaves with this one.

Beyond this week

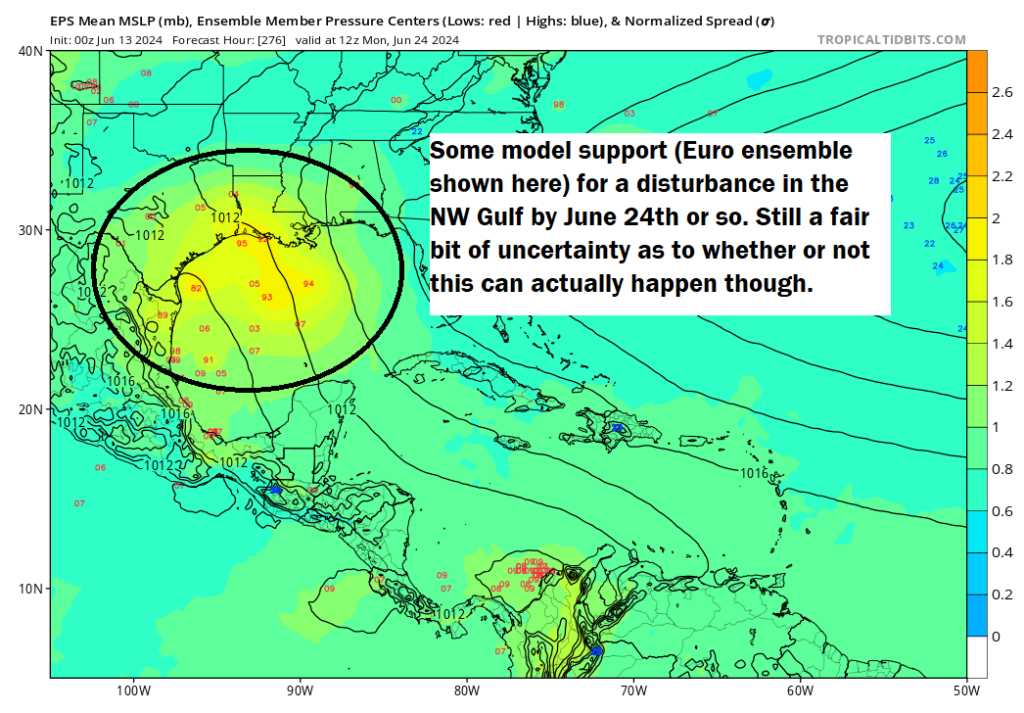

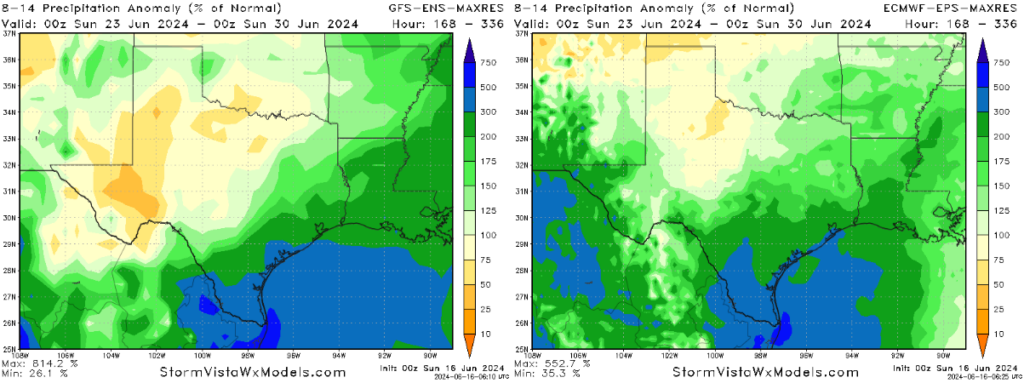

It still appears that another system may try to form, spiraling around the Central American gyre next week. Details remain uncertain, but it’s pretty evident that modeling supports a continued rainy pattern in Texas.

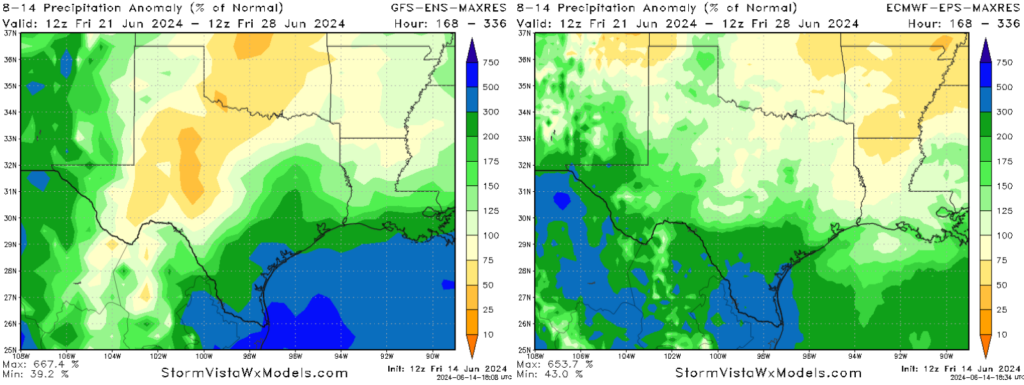

Both the GFS and European ensemble members shown above indicate agreement on about 200 to 500 percent of normal rainfall for the 8 to 14 day period. This would be 1 to 2 inches more rainfall than usual, on average. So we’ll need to continue monitoring Texas and Louisiana for potential flooding concerns into next week too.

Outside of the western Gulf it looks quiet, and hopefully that area will begin to quiet down a bit too after next week.