Headlines

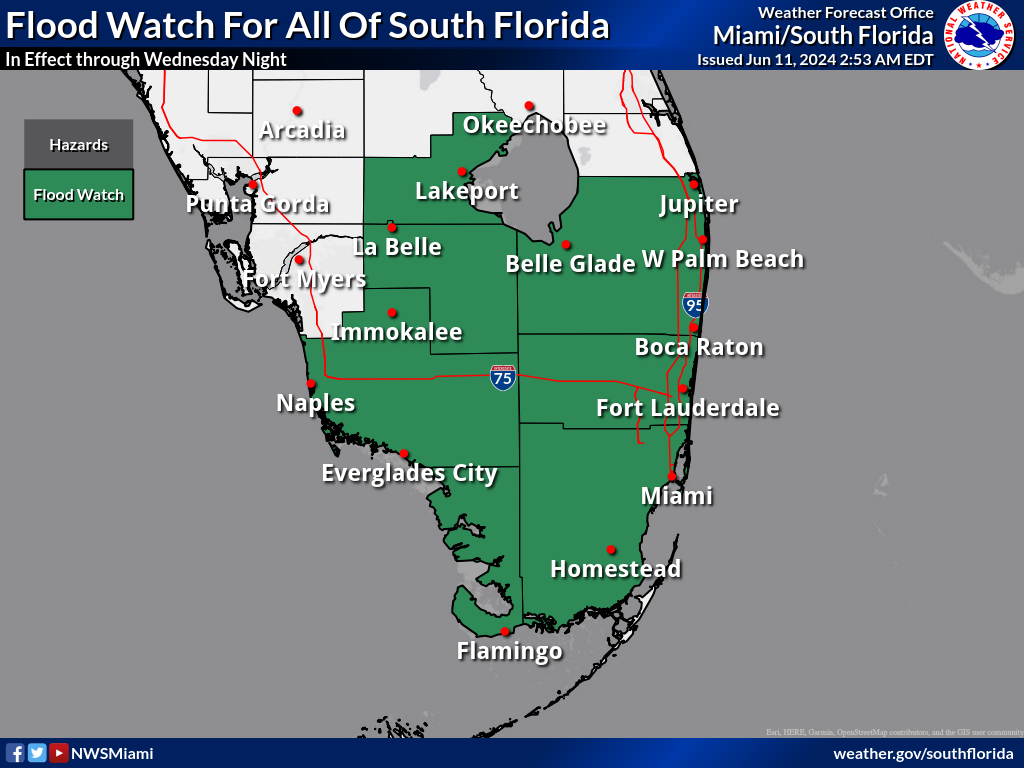

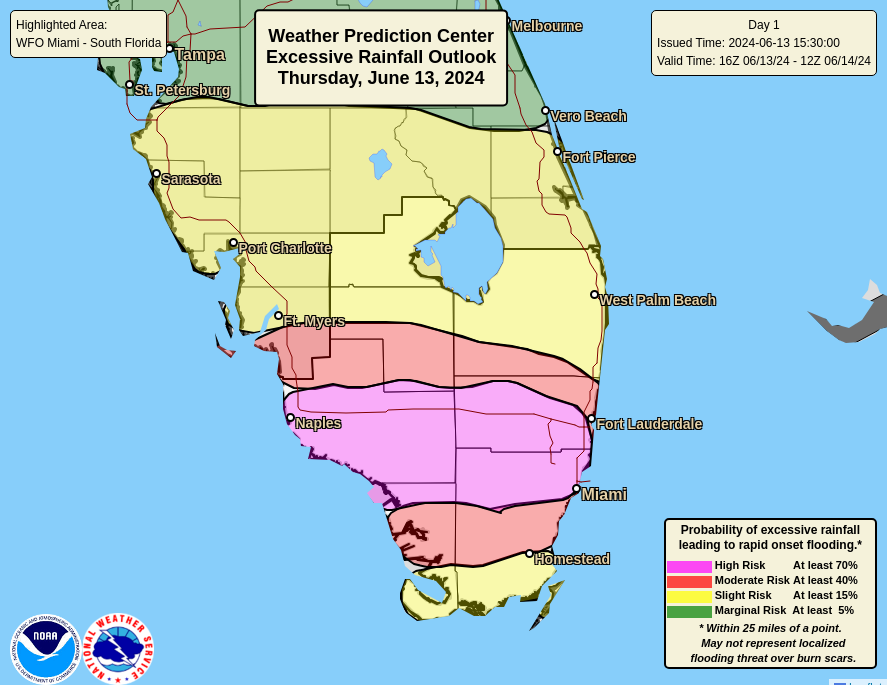

- Additional heavy rain is likely in Florida today, with a high risk for flooding and excessive totals in South Florida, including the Miami and Fort Lauderdale areas and Naples also.

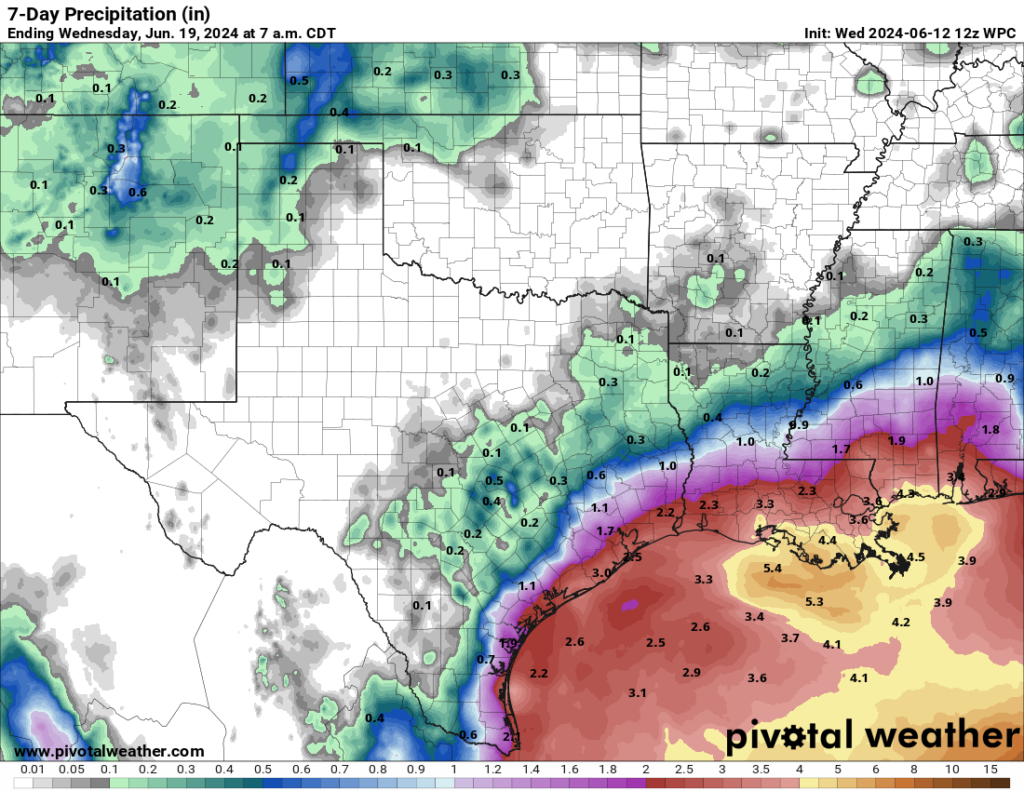

- Rain, ideally more manageable, will shift to Louisiana, Texas, and Mexico next week, while a separate tropical system may form in the Bay of Campeche and track into Mexico.

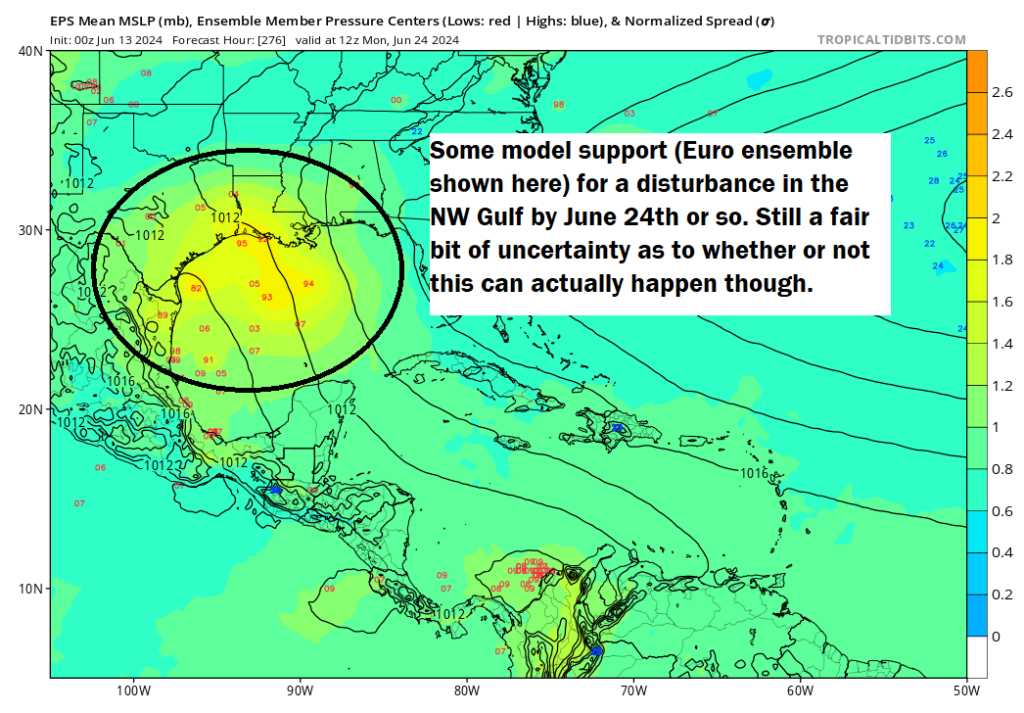

- An additional tropical entity may try to form the week of June 24th in the western Gulf.

Florida flooding risks still not over

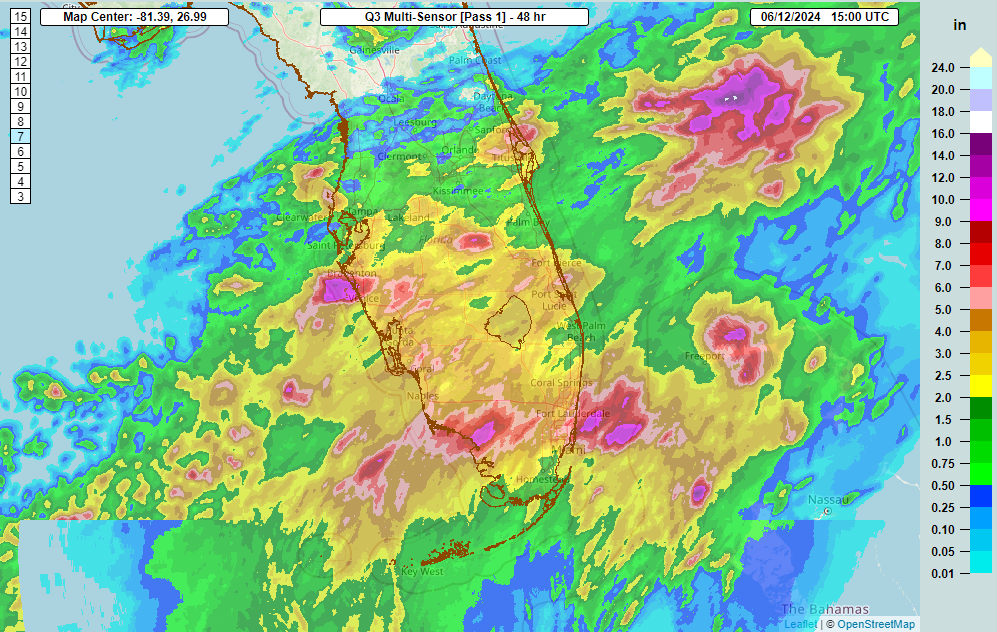

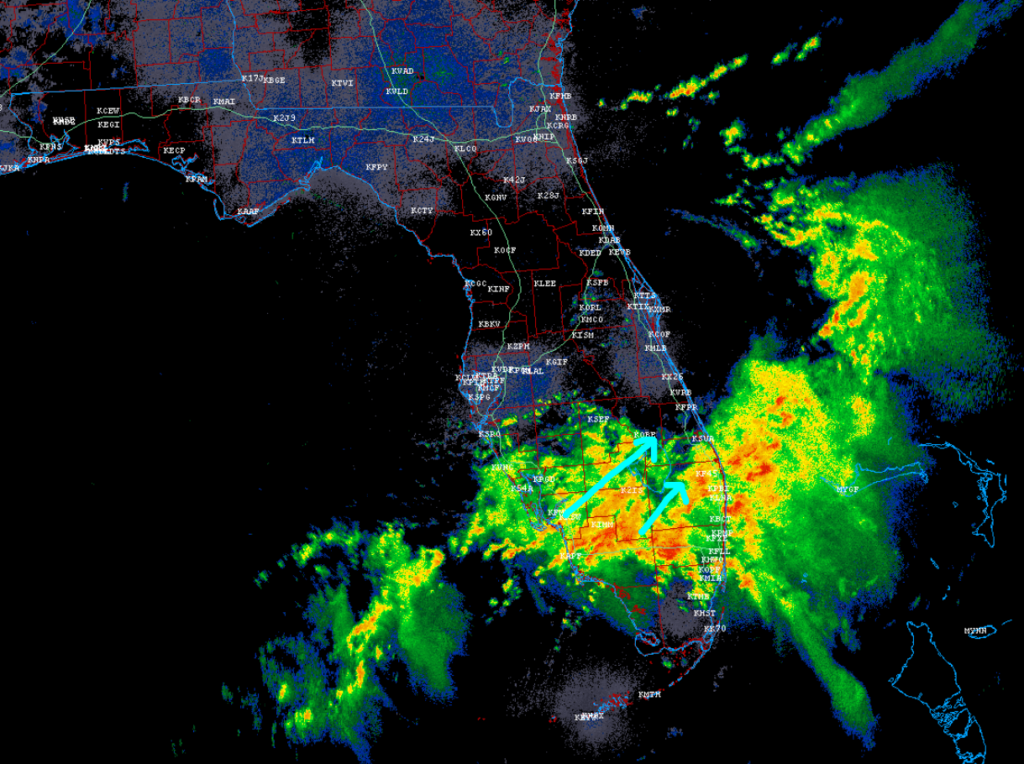

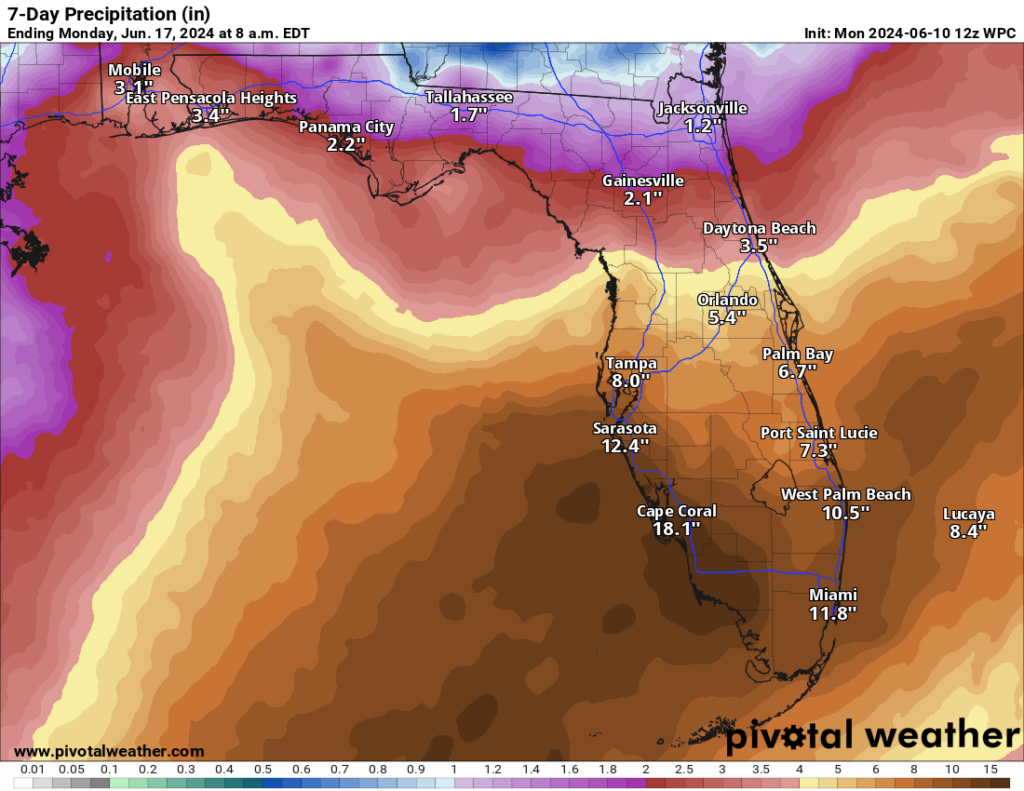

After a wild day yesterday with flash flood emergencies posted between Miami and West Palm Beach, we’re seeing the next round of heavy rainfall pushing across the Peninsula from northwest to southeast.

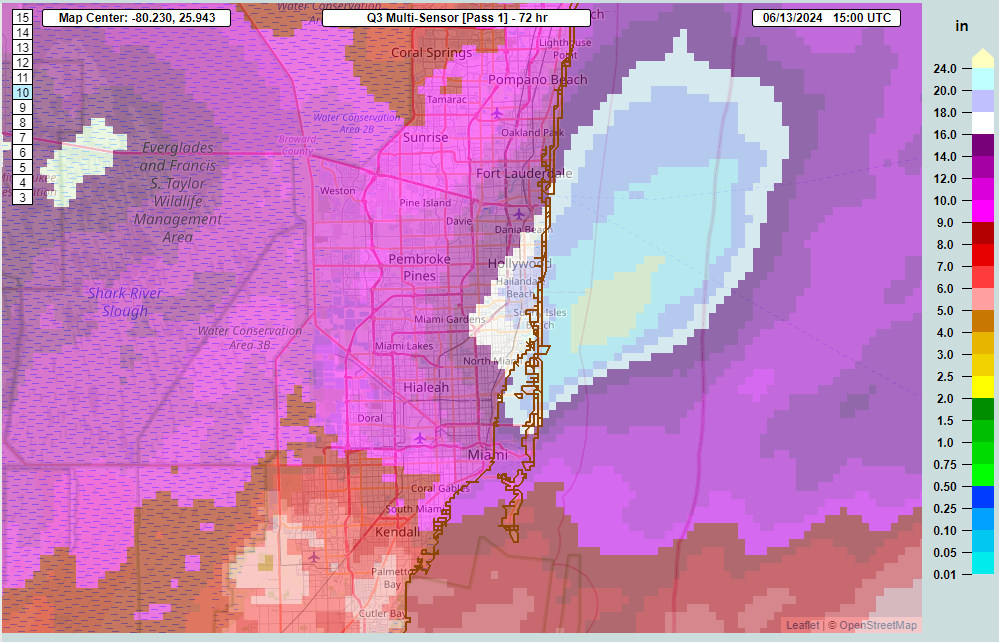

Yesterday was the third wettest day since 2000 in Fort Lauderdale with 9.54 inches of rainfall. It was Miami’s fifth wettest day since 2000 with just over 6 inches of rain. So far this week, some parts of the immediate coast have seen upwards of 20 inches of rainfall.

North Miami has had 20.43″, Hallandale and Hollywood are over 19 inches, and not to be outdone, Big Cypress National Preserve in Collier County has seen 25 inches of rain!

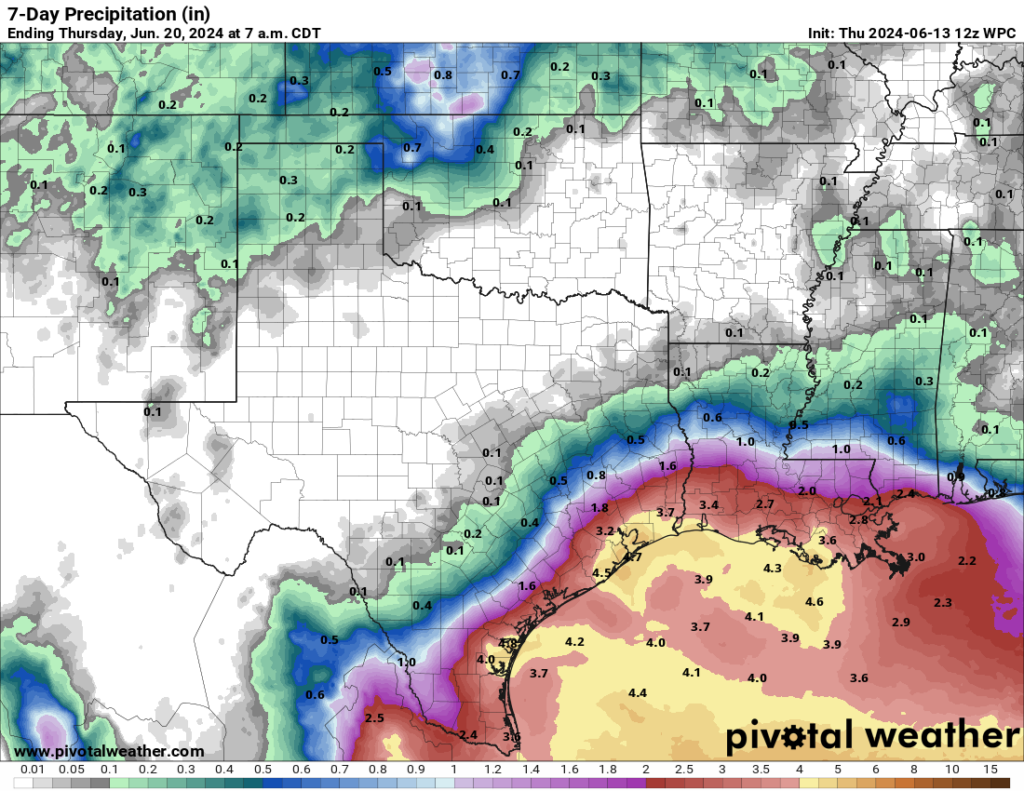

Today should hopefully the last really dicey day for Florida, but it’s definitely not looking great with all this moisture inbound. As a result, the Weather Prediction Center has upgraded South Florida to a high risk of excessive rainfall and flash flooding. Anywhere from 4 to 8 inches of additional rain are possible today, with locally higher amounts. The atmosphere is about as juiced up as you’ll ever see in June in Florida, which means that it will be capable of dumping very heavy rainfall at very high rates.

The hope is that the rain becomes more intermittent and a little less intense for Friday and the weekend. There will still likely be some showers or heavy rain around, but it should space itself out a bit.

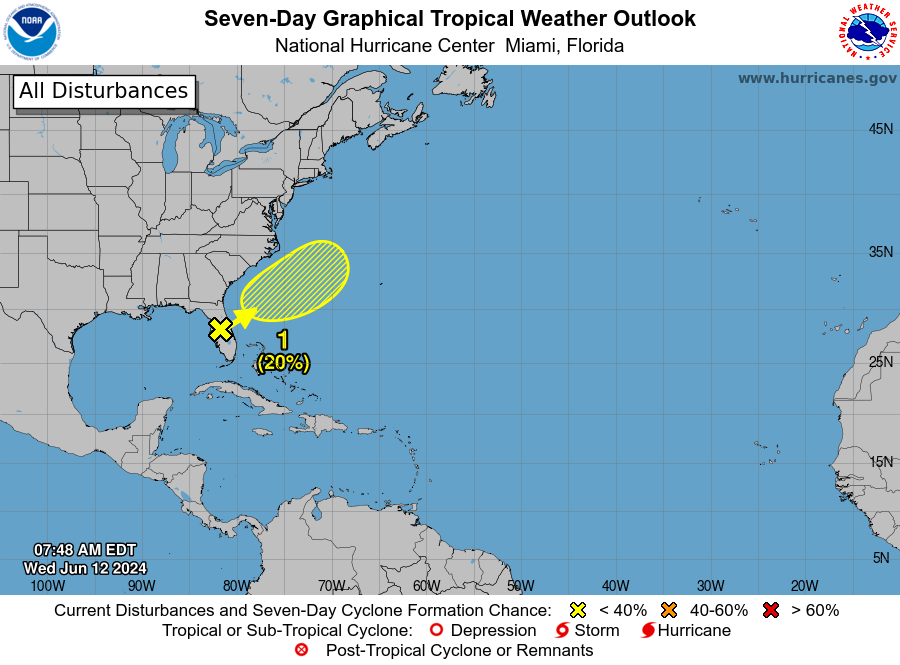

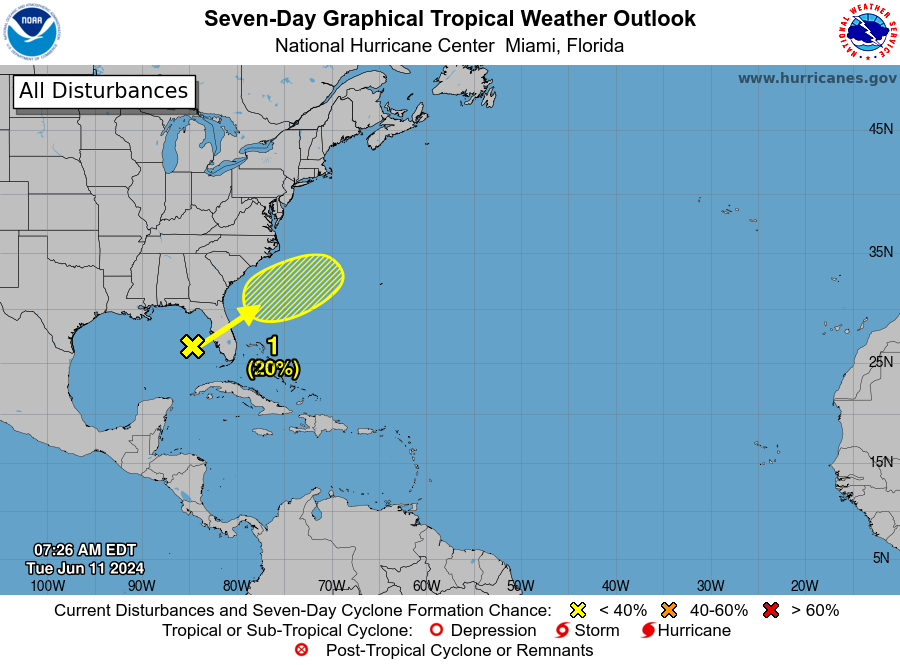

Invest 90L’s future murky

Meanwhile, Invest 90L, which helped contribute to the massive rains in Florida yesterday is on its way out over the Atlantic. Odds of development are minimal, and for all intents and purposes, this should be a non-event to monitor.

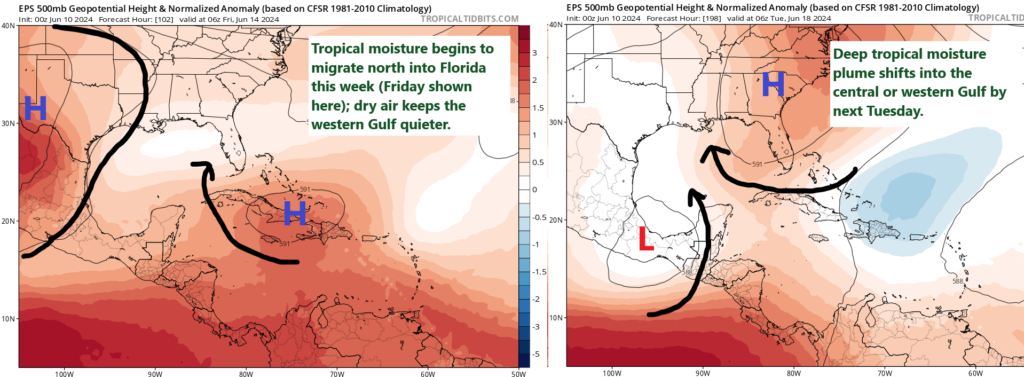

Next week’s potential Gulf system

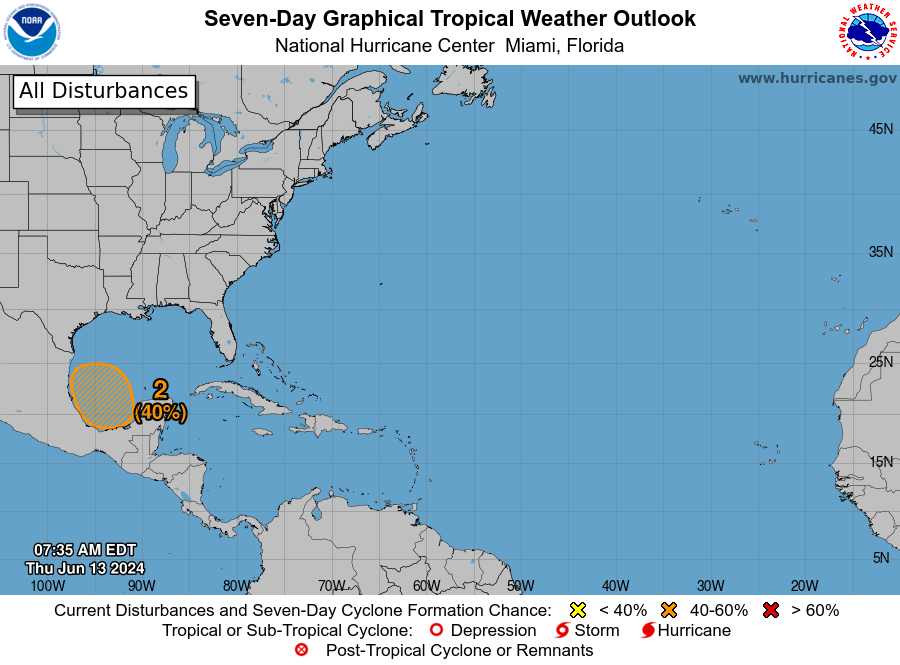

Meanwhile, the odds of development in the western Gulf of Mexico continue to inch upwards today. The National Hurricane Center is now assigning a 40 percent chance of development in the Bay of Campeche for next week.

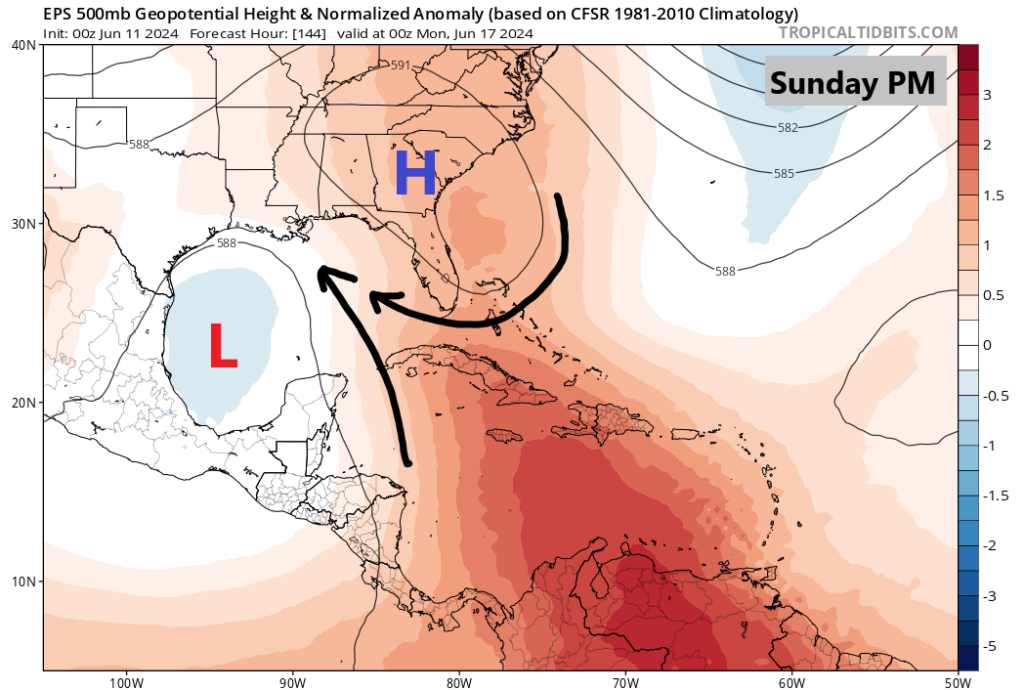

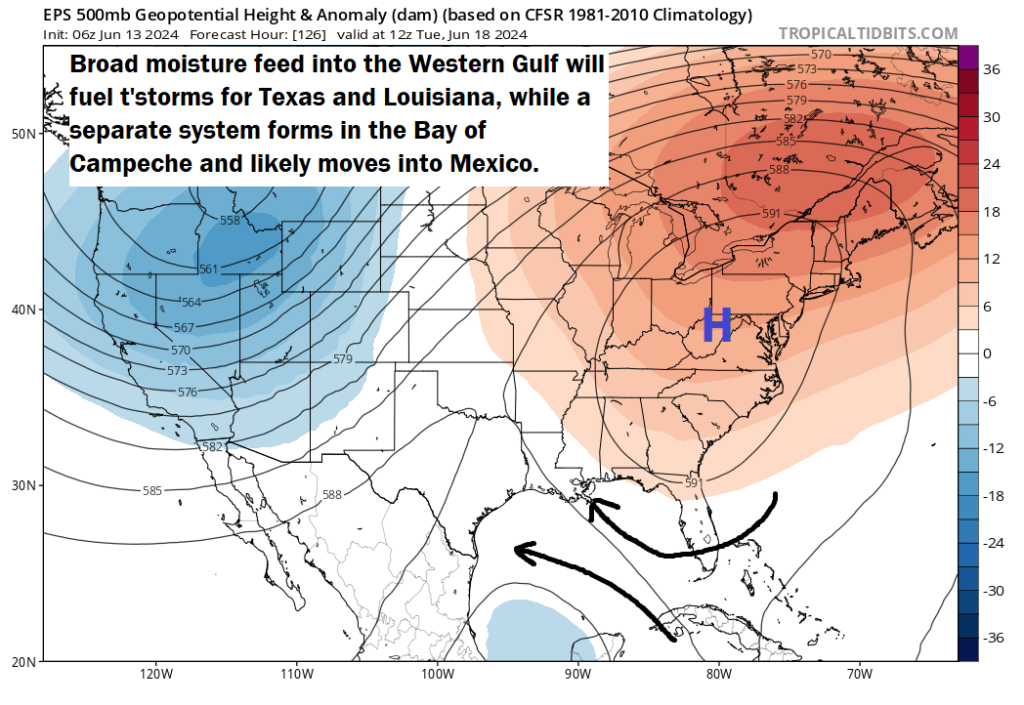

What to make of this? As we’ve been discussing this week, the moisture axis aimed at Florida this week will reorient next week as high pressure sets up over the Eastern U.S., kicking off a pretty significant heat wave for much of the country. This will direct high moisture into Louisiana and Texas, coupled with the developing low in the Bay of Campeche.

You need to think of this as two separate but related entities. On the one hand, we’re going to see a broad “fetch” across the Gulf allowing for more numerous showers and thunderstorms in Texas and Louisiana perhaps, as well as northern Mexico. The hope is that most of this rain will be manageable in nature with only minor flooding concerns at times. We’ll keep watching.

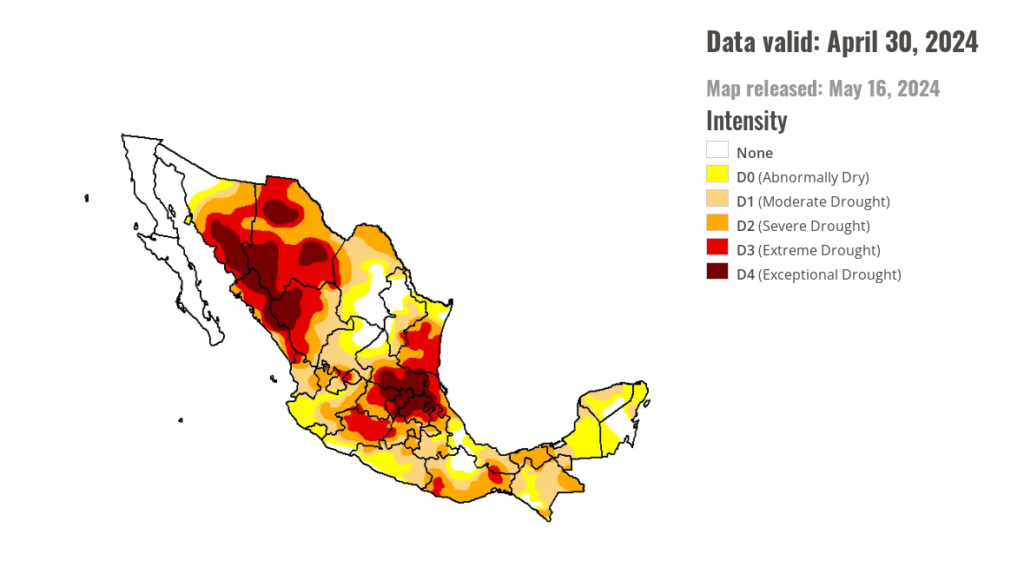

On the other hand, a formal tropical system will likely try to form in the Bay of Campeche, likely also directed west or west-northwest, which pushes it rather quickly ashore in Mexico by later next week. Rain will be mostly welcome in Mexico, which, as we noted yesterday has been mired in record heat and drought. There’s been hardly a cooler than normal day there since April.

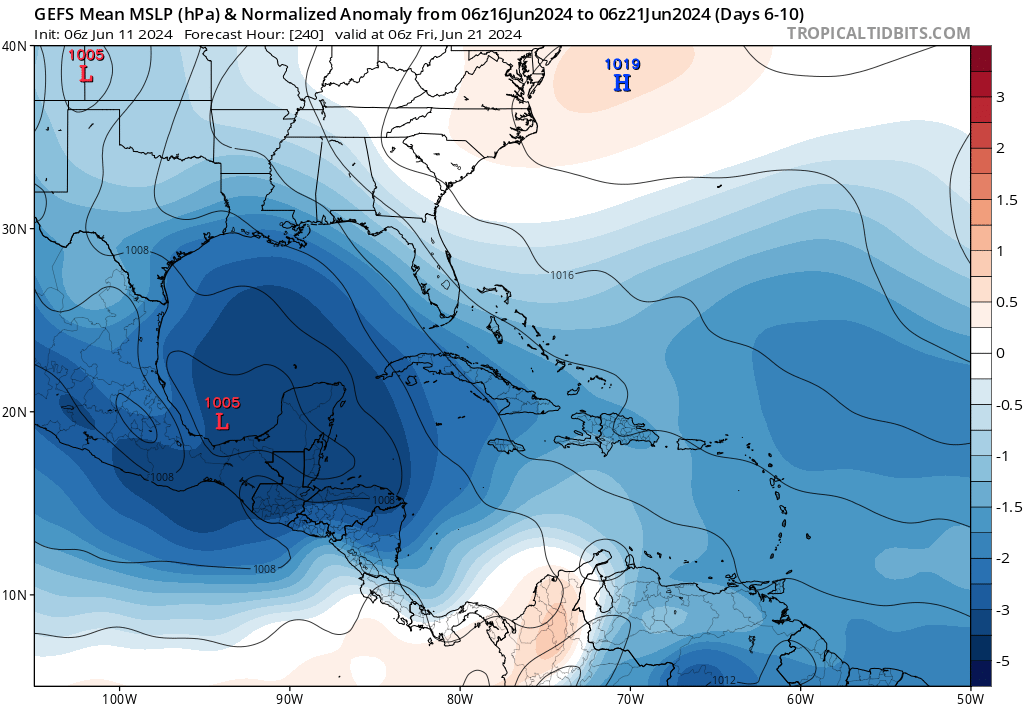

More Gulf gyration to come?

We have a little bit of a new wrinkle today, and this involves the potential for a second western Gulf system by next weekend or so. This “gyre” type setup in Central America is causing us headaches, and another disturbance may pivot from the southwest Caribbean to just north of the Yucatan by next weekend. From there it would probably move quickly north toward Texas, Louisiana, or Mississippi.

Whether there will be enough time or a stable enough environment for more development to occur, it’s too soon to say. But the timeline is next weekend into early the week of June 24th. We’ll keep you posted.