One-sentence summary

There is one area in the Central Atlantic that we’re tracking, but we don’t expect it to develop; otherwise things are blissfully quiet for early August.

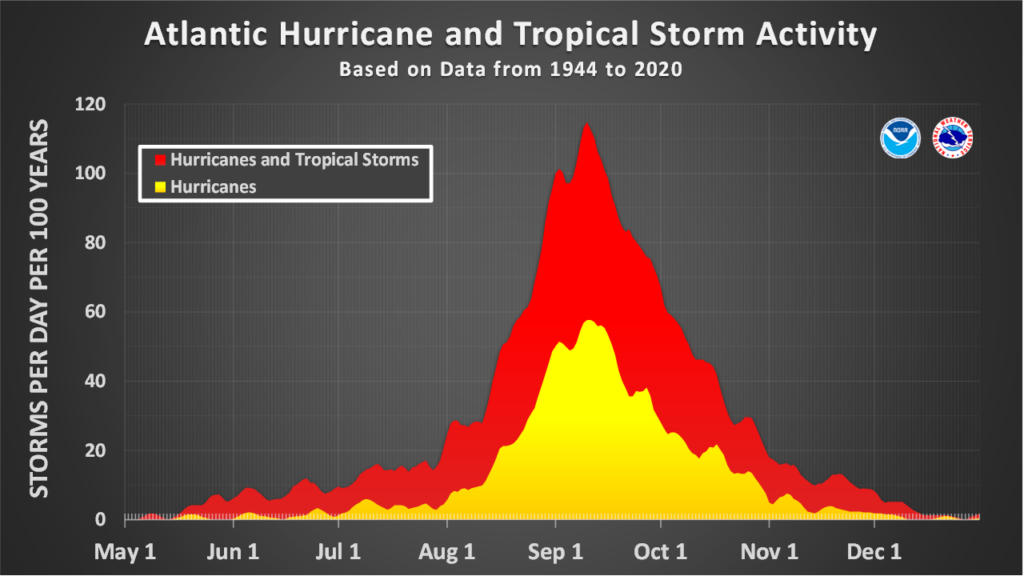

Approaching “go” time for the Atlantic season

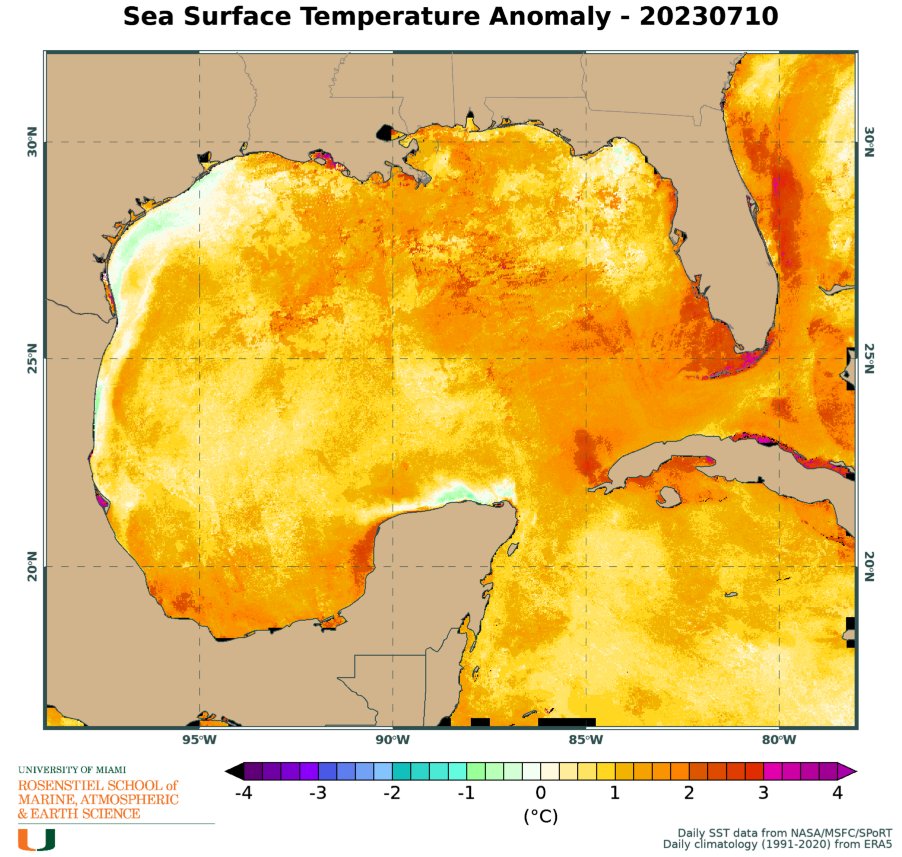

The start of August means that we’re now just a couple of weeks from when activity in the Atlantic Ocean often starts to pick up. The outlook this season is complicated because of several factors. One is that sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic basin are absolutely sizzling. During the last month the “main development region,” a stretch of tropical water between Africa and the Caribbean Sea where most major Atlantic hurricanes develop, the sea surface temperature averaged 82.4° Fahrenheit, a full degree above any previous July. This trend will certainly continue into the heart of hurricane season, and is very concerning.

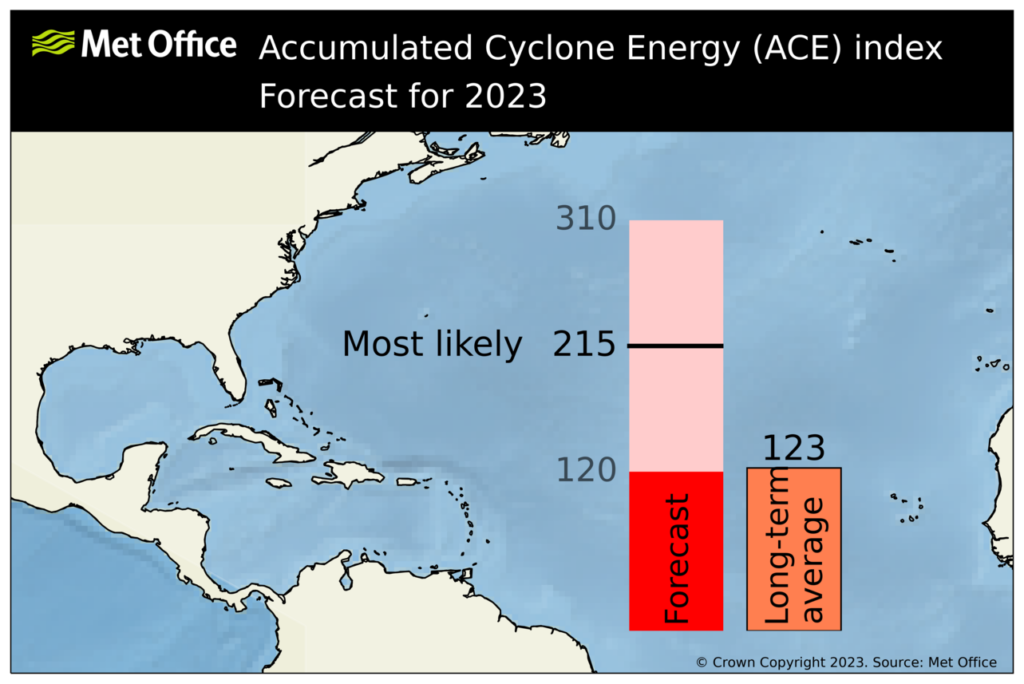

At the same time, with El Niño active in the Pacific Ocean, we’re seeing somewhat higher wind shear and sinking air over the Atlantic Ocean. So far, this has helped to dampen activity in the deep tropics. But we’re about to get to the point in the season where the African wave train rumbles to life, and it’s not clear to me that there will be enough shear to overpower the formation of some very strong and threatening hurricanes. To that end, the United Kingdom’s Met Office released an updated seasonal forecast that calls for a very busy season with 19 named storms and, worryingly, 6 major hurricanes. Overall, based on the Accumulated Cyclone Energy index, the British forecasters anticipate about twice as much activity as normal.

Seasonal forecasts are just a guide, of course. But we’re going to need to keep a close eye on the tropics for the next 10 to 12 weeks.

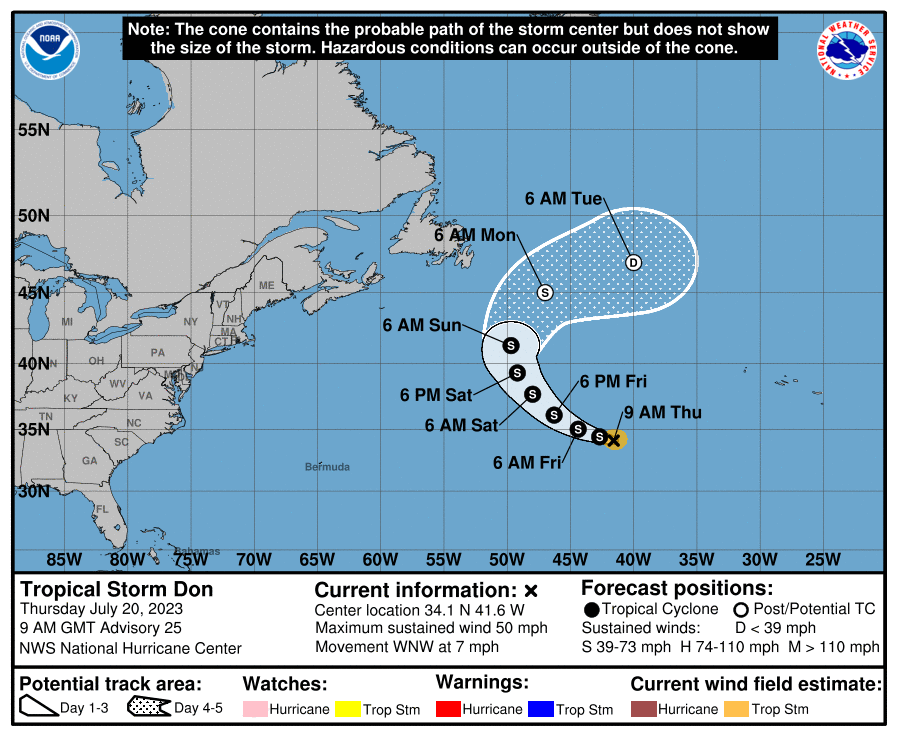

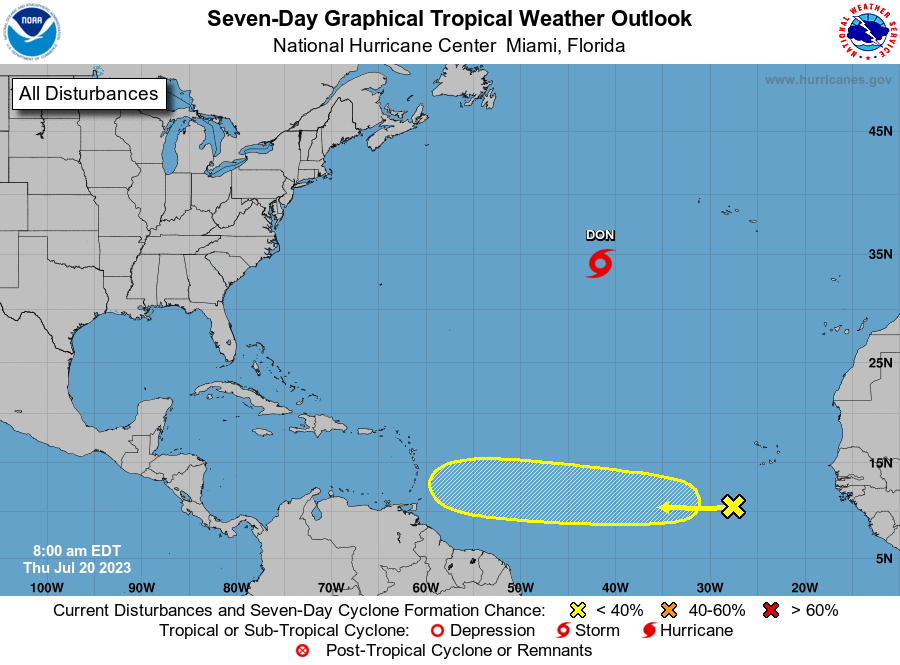

Happening now: A disorganized wave

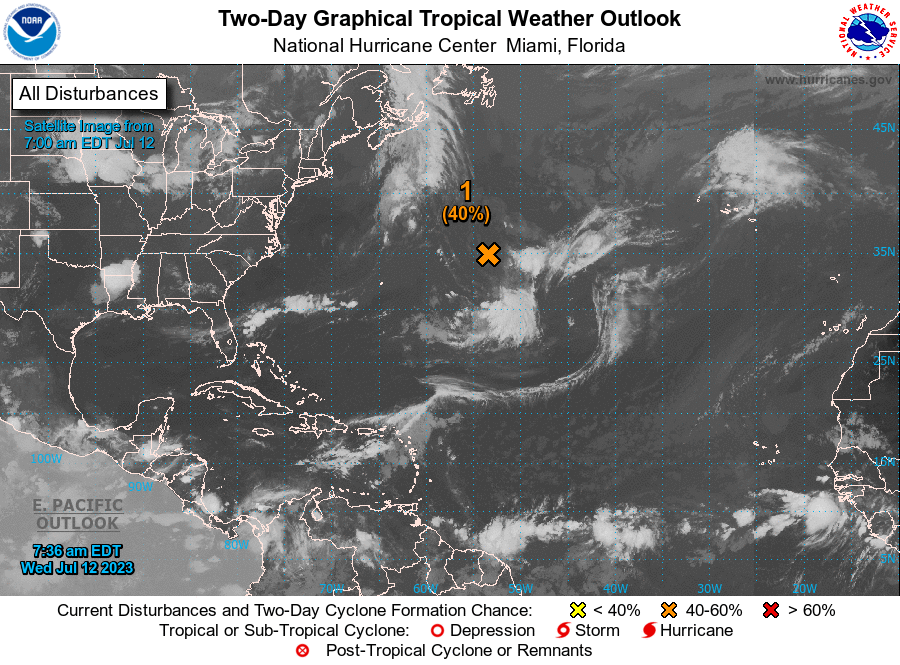

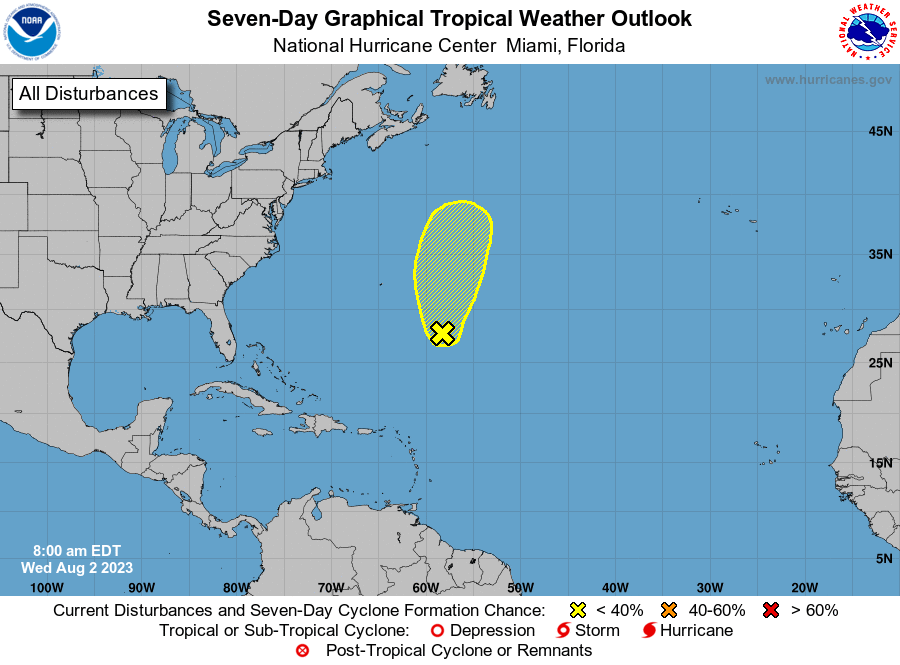

The only system of note in the Atlantic tropics right now is a tropical wave several hundred miles east of Bermuda. It’s struggling at the moment, but has a slight chance of becoming a tropical depression or storm over the next week. As its contending against dust and shear, I’d guess the end is near. But we’ll see. Regardless, it’s not a threat to land anywhere so we can pretty much ignore it. (Well, that is, we could ignore it if we weren’t a website dedicated to covering tropical activity in the Atlantic basin).

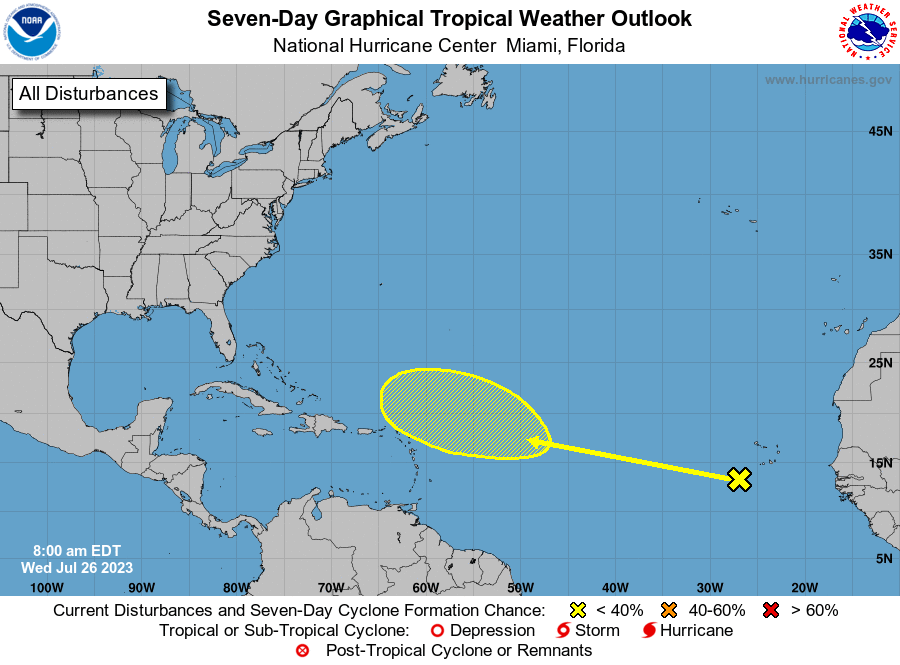

The medium range (days 6 to 10): Off the coast of Africa

As Matt noted on Tuesday, a tropical wave moving off the coast of Africa at present could be something to watch in a week or so as it slowly plods across the Atlantic Ocean. If this becomes a tropical depression, due to steering currents in the Atlantic, it probably would move toward the Caribbean Sea. Still, this is no sure thing, and probably not something we should be too concerned about at the moment.

Fantasyland (beyond day 10): All quiet on the Western front?

In the overnight runs we’re not seeing the global models get too excited about anything in the next two weeks. That doesn’t mean nothing will happen, it’s just that right now there is nothing obvious out there that will become a problem. The tropics are unpredictable like that.